The Trinity Is a Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptism: Valid and Invalid

BAPTISM: VALID AND INVALID The following information has been provided to the Office of Worship and Christian Initiation by Father Jerry Plotkowski, Judicial Vicar. It is our hope that it will help you in discerning the canonical status of your candidates. BAPTISM IN PROTESTANT RELIGIONS Most Protestant baptisms are recognized as valid baptisms. Some are not. It is very difficult to question the validity of a baptism because of an intention either on the part of the minister or on the part of the one being baptized. ADVENTISTS: Water baptism is by immersion with the Trinitarian formula. Valid. Baptism is given at the age of reason. A dedication ceremony is given to infants. The two ceremonies are separate. (Many Protestant religions have the dedication ceremony or other ceremony, which is not a baptism. If the church has the dedication ceremony, baptism is generally not conferred until the age of reason or until the approximate age of 13). AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL: Baptism with water by sprinkling, pouring, or dunking. Trinitarian form is used. Valid. There is an open door ceremony, which is not baptism. AMISH: This is coupled with Mennonites. No infant baptism. The rite of baptism seems valid. ANGLICAN: Valid baptism. APOSTOLIC CHURCH: An affirmative decision has been granted in one case involving "baptism" in the apostolic church. The minister baptized according to the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, and not St. Matthew. The form used was: "We baptize you into the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins, and you shall receive a gift of the Holy Ghost." No Trinitarian form was used. -

The Function of Perichoresis and the Divine Incomprehensibility

Wrj 64 (2002) 289-306 THE FUNCTION OF PERICHORESIS AND THE DIVINE INCOMPREHENSIBILITY LANE G. TIPTON I. Introduction Reformed Trinitarian theism best encapsulates the theology of Cornelius Van Til. He says, "Basic to all the doctrines of Christian theism is that of the self-contained God, or, if we wish, that of the ontological Trinity. It is this notion of the ontological Trinity that ultimately controls a truly Christian methodology."1 Again, "unless we may hold to the presupposition of the self- contained ontological Trinity, human rationality itself is a mirage."2 The onto- logical Trinity provides the architectonic principle in Van Til's theology and apologetic. However, the doctrine of the Trinity in Van Til's thought is as controversial as it is foundational. Regarding the Trinity, Van Til makes the following state- ments, which, when taken together, provide a formulation which John Frame called "a very bold theological move."3 What is this bold move? Van Til argues: It is sometimes asserted that we can prove to men that we are not assuming anything that they ought to consider irrational, inasmuch as we say that God is one in essence and three in person. We therefore claim that we have not asserted unity and trinity of exactly the same thing. Yet this is not the whole truth of the matter. We do assert that God, that is, the whole Godhead, is one person.4 Notice that Van Til does not assert that the person/essence formulation is false, or in need of replacement; instead, he argues that the statement "God is one in essence and three in person" does not yield the "whole truth of the matter." Again Van Til says, "We must hold that God's being holds an absolute numeri- cal identity. -

Trinitarian & Christological Orthodoxy

A Brief Overview of Christian Orthodoxy: Trinitarian and Christological Controversies By Charles Williams Last revised: August 9, 2009 The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (381 A.D.) Concerning Against Text God the Father Gnosticism & We believe in one God Marcionism The Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, Valentinianism And of all things visible and invisible; God the Son And in one Lord Jesus Christ The only-begotten Son of God, Adoptionism Begotten of his Father before all time, God of God, Light of Light, Arianism Very God of very God, Begotten, not created, Being of one substance with the Father, By whom all things were made; Who for us and our salvation Came down from heaven, Adoptionism And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost Of the virgin Mary, Apollinarianism And was made man; Docetism And was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; And the third day he rose again According to the Scriptures, And ascended into heaven, And sits at the right hand of the Father; Modalism And he shall come again, with glory, To judge both the quick and the dead; Whose kingdom shall have no end. God the Holy Spirit Macedonianism And we believe in the Holy Ghost the Lord And Giver of Life Who proceeds from the Father [and the Son]*; Who with the Father and the Son Together is worshiped and glorified; Marcionism Who spake by the Prophets. The Church And we believe in one holy Catholic & Last Things And Apostolic Church; Donatism We acknowledge one Baptism For the remission of sins; Gnosticism And we look for the resurrection of the dead, And the life of the world to come. -

Valid-Invalid Baptisms Valid

Archdiocese of Los Angeles- Office of Divine Worship- Valid -Invalid Baptism VALID-INVALID BAPTISMS VALID: The following is a list of baptisms which are considered valid, as both water (pouring, sprinkling, or immersing the one baptized) and the Trinitarian formula (“I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”) are used. Also, the minister must intend to do what the Church does when baptizing. • All Eastern non-Catholics (including all Orthodox churches) • Adventist Valid Baptism • African Methodist Episcopal • Amish/Mennonite • Anglican / Church of England • Assembly of God • Baptists • Chinese Catholic Baptism/Confirmation recognized • Chinese Christian • Christian and Missionary Alliance • Christian Fellowship • Church of the Brethren • Church of Christ • Church of God • Church of the Nazarene • Community of Pope Pius X (Lefebvre) Baptism/Confirmation recognized • Congregational • Disciples of Christ • Dutch Reformed • Eastern Non-Catholics (Orthodox) Baptism/Confirmation recognized • Episcopal • Evangelical • Evangelical Church of Covenant • Evangelical United Brethren • International Council of Community • Liberal Catholic • Lutheran • Methodist • Mennonite • Missionary Hill • Moravian July 2021 Archdiocese of Los Angeles- Office of Divine Worship- Valid -Invalid Baptism • New Apostolic Church • Church of the Nazarene • Old Catholic • Old Roman Catholic • Orthodox (see Eastern above) Baptism/Confirmation recognized • Polish National • Presbyterian • Reformed • Seventh Day Adventist • United Church • United Church of Canada • United Church of Christ • United Reformed • United Church of Australia • Waldensian • Zion DOUBTFUL: The following communities have baptismal practices which are not uniform and are considered to be doubtful, requiring an investigation into each case. Some of their communities have valid baptism, others do not. Mennonite Moravian Pentecostal Seventh Day Adventist INVALID: The following is a list (albeit incomplete) of baptisms considered to be invalid, due to a number of reasons. -

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance Kate Helen Dugdale Submitted to fulfil the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, November 2016. 1 2 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that rather than focusing on the Church as an institution, social grouping, or volunteer society, the study of ecclesiology must begin with a robust investigation of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Utilising the work of Thomas F. Torrance, it proposes that the Church is to be understood as an empirical community in space and time that is primarily shaped by the perichoretic communion of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, revealed by the economic work of the Son and the Spirit. The Church’s historical existence is thus subordinate to the Church’s relation to the Triune God, which is why the doctrine of the Trinity is assigned a regulative influence in Torrance’s work. This does not exclude the essential nature of other doctrines, but gives pre-eminence to the doctrine of the Trinity as the foundational article for ecclesiology. The methodology of this thesis is one of constructive analysis, involving a critical and constructive appreciation of Torrance’s work, and then exploring how further dialogue with Torrance’s work can be fruitfully undertaken. Part A (Chapters 1-5) focuses on the theological architectonics of Torrance’s ecclesiology, emphasising that the doctrine of the Trinity has precedence over ecclesiology. While the doctrine of the Church is the immediate object of our consideration, we cannot begin by considering the Church as a spatiotemporal institution, but rather must look ‘through the Church’ to find its dimension of depth, which is the Holy Trinity. -

Homily 31 January 2016 Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Homily 31 January 2016 Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time Jeremiah 1:4-5,17-19; Psalm 71:1-2,3-4,5-6,15-17; 1 Corinthians 12:31-13:13 [72] —— But I shall show you a still more excellent way. —— Every other month I teach the theology of baptism class for new parents. We begin with the Trinitarian formula, the essential words of the sacrament: “I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” So I ask the parents: “What does the Trinity mean to you? Why does it matter to you that God is a Trinity of Persons and not just one person or even two or four? Do you know how they almost always answer that question? They sit very quietly. It’s a hard question but an important one because the answer ought to influence how we think about family life and friendship, and how we think about ourselves and about society. So after a few moments of silence, I say to the parents: Let me tell you about Richard of St Victor. He was a mystical theologian who lived more than 800 years ago and who wrote a reflection of the Trinity that I’ve found very helpful. He begins his reflection with a simple statement from St. John: “God is love …” Well, he thought, if God is love then he has to be perfect love. But if there was only one person in God, then God’s love would be self-love, and that just can’t be, for self-love is at best an imperfect kind of love. -

The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons Jackson Jay Lashier Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Lashier, Jackson Jay, "The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 109. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/109 THE TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY OF IRENAEUS OF LYONS by Jackson Lashier, B.A., M.Div. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABSTRACT THE TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY OF IRENAEUS OF LYONS Jackson Lashier, B.A., M.Div. Marquette University, 2011 This dissertation is a study of the Trinitarian theology of Irenaeus of Lyons. With the exception of two recent studies, Irenaeus’ Trinitarian theology, particularly in its immanent manifestation, has been devalued by scholarship due to his early dates and his stated purpose of avoiding speculative theology. In contrast to this majority opinion, I argue that Irenaeus’ works show a mature understanding of the Trinity, in both its immanent and economic manifestations, which is occasioned by Valentinianism. Moreover, his Trinitarian theology represents a significant advancement upon that of his sources, the so-called apologists, whose understanding of the divine nature converges in many respects with Valentinian theology. I display this advancement by comparing the thought of Irenaeus with that of Justin, Athenagoras, and Theophilus, on Trinitarian themes. Irenaeus develops Trinitarian theology in the following ways. First, he defines God’s nature as spirit, thus maintaining the divine transcendence through God’s higher order of being as opposed to the use of spatial imagery (God is separated/far away from creation). -

Handout: 2 Corinthians Lesson 5

Handout: 2 Corinthians Lesson 5 In 11:5-6, Paul defends himself and his ministry against the accusations of the visiting ministers. He begins by making the first of several points in his defense: 1. He is not inferior to the so-called “superapostles.” Paul does not state but infers that, after all, he was personally commissioned by the resurrected Christ to carry His Gospel to the Gentiles. It is a claim the others cannot make. 2. Even if he is untrained in rhetoric, he has received knowledge directly from Christ and the authority to preach the Gospel of salvation. Paul makes three accusations against the men who he writes have tried to mislead the Corinthians: 1. They are false apostles. 2. They are deceitful workers. 3. They are those who falsely present themselves as true apostles of Christ. In 11:22-23, Paul asks a series of three rhetorical questions followed by his answers in comparing himself with the false teachers: 1. Are they Hebrews? So am I. 2. Are they Israelites? So am I. 3. Are they ministers of Christ? (I am talking like an insane person.) I am still more, with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, far worse beatings, and numerous brushes with death. Since Paul identifies the false ministers as Hebrews and Israelites, they are probably Ebionite Messianic Jews. The Ebionite movement existed during the early centuries of the Christian Era. The Ebionites accepted Jesus as the promised Messiah, but they rejected His divinity and insisted on the necessity of continuing to follow the old Sinai Covenant laws and rites. -

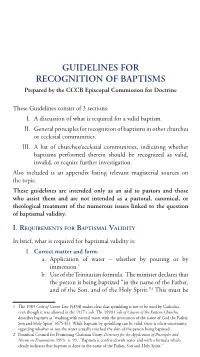

Guidelines for Recognition of Baptisms

First Church of Christ, Scientist Unitarian Universalist I (Mary Baker Eddy) - no baptism I Unitarians I Foursquare Gospel Church V United Church of Christ V General Assembly of Spiritualists I United Church of Canada V Hephzibah Faith Missionary Association I United Reformed V House of David Church I United Society of Believers I Iglesia ni Kristo (Phillippines) I Uniting Church in Australia V GUIDELINES FOR Independent Church of Filipino Christians I Universal Emancipation Church I RECOGNITION OF BAPTISMS Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watchtower Society) I Waldensian V Liberal Catholic Church V Worldwide Church of God (invalid before mid-1990’s) I Prepared by the CCCB Episcopal Commission for Doctrine Lutheran V Zion V Masons / Freemasons - no baptism I These Guidelines consist of 3 sections: Mennonite Churches ? I. A discussion of what is required for a valid baptism. APPENDIX: SOME MAGISTERIAL SOURCES TO BE CONSULTED Methodist V II. General principles for recognition of baptisms in other churches Metropolitan Community Church ? 1983 Code of Canon Law, n. 849-878. or ecclesial communities. Moonies (Reunification Church) I 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, n. 672-691. III. A list of churches/ecclesial communities, indicating whether Moravian Church ? Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity,Directory for the baptisms performed therein should be recognized as valid, National David Spiritual Temple of Christ Church Union I Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, 1993, n. 92-101. invalid, or require further investigation. National Spiritualist Association I Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1213-1284. Also included is an appendix listing relevant magisterial sources on The New Church I the topic. -

The Spirit of Cities

THE SPIRIT OF CITIES T H E S P I R I T OF CITIES Why the Identity of a City Matters in a Global Age Daniel A. Bell and Avner de-Shalit princeton university press princeton oxford Copyright © 2011 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Third printing, and first paperback printing, with a new preface by the authors, 2014 Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-15969-0 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Bell, Daniel (Daniel A.), 1964– The spirit of cities : why the identity of a city matters in a global age / Daniel A. Bell and Avner de-Shalit. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15144-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Cities and towns—Social aspects. 2. Identity politics. 3. Urban policy. I. De-Shalit, Avner. II. Title. HT151.B415 2011 307.76—dc23 2011019200 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Garamond and Archer Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 TO CITY-ZENS CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Preface to the Paperback Edition: The City and Identity xi Introduction: Civicism 1 Jerusalem: The City of Religion 18 Montreal: The City of Language(s) 56 Singapore: The City of Nation Building 78 Hong Kong: The City of Materialism 111 Beijing: The City of Political Power 140 Oxford: The City of Learning 161 Berlin: The City of (In)Tolerance 191 Paris: The City of Romance 222 New York: The City of Ambition 249 Notes 279 Selected Bibliography 321 Index 333 vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The idea for this book came to us in early September 2001, when we were walk- ing the streets of San Francisco (the official reason for the trip was a meeting of the American Political Science Association). -

Christian Perspective of Understanding the Divinity of God

Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 4, Issue 2, 2020, PP 1-5 ISSN 2637-5907 Christian Perspective of Understanding the Divinity of God Apostle Devaprasad Department of Christian Studies, University of Madras, India *Corresponding Author: Apostle Devaprasad, Department of Christian Studies, University of Madras, India, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT There are different kinds of people in the world and these people follow different religions. They worship different gods and goddesses. Some believe that God exists in many which is popularly known as polytheism while others especially the Christians, Muslims and Jews believe there exist only one god which is known as Monotheism. Muslims and Jews strongly identify God as monotheistic existing in single nature while the Christians who also believe in Monotheism understand the divinity of God in a different manner which is far distinctive to that of the belief of Muslims and Jews. Christians understand God to be three members in one single entity. The one entity emphasizes monotheism whereas the three members emphasizes trinitarianism. This trinitarianism finally led to the concept of the famous “Trinity”. The history and concept of trinity is briefly described in this article. Apart from this, the perspective of how Christianity sees and worship God is also described in this article. Keywords: Trinity, Godhead, Father, Son, Holy Spirit, nature, Divinity, Transcendental, Hypostases, Homoousis, Omnipotent, Omniscient. INTRODUCTION Before the Council of Nicaea The Christian doctrine of the word Trinity is Tertullian was the first to use the term “Trinity” derived from the Latin word “Trinitas” which and to formulate the doctrine, but his means “Triad” which itself is derived from formulation involved subordination of Son to another Latin word “trinus” meaning “threefold”. -

People of God, Body of Christ, Koinonia of Spirit: the Role of Ethical Ecclesiology in Paul’S “Trinitarian” Language

ATR/87:2 People of God, Body of Christ, Koinonia of Spirit: The Role of Ethical Ecclesiology in Paul’s “Trinitarian” Language A. Katherine Grieb* The relationship between trinitarian doctrine and human society is intensely debated today. Can Paul’s ethical ecclesiology help? Paul’s missionary theology requires a careful working out of the interrelations of the term “people of God” taken from Israel’s Scriptures, and another term, the “body of Christ,” deriving from the sacraments and popular social theory. Are these opposing ec- clesial descriptions? Has one superseded the other? At issue is nothing less than the integrity of God. This paper argues that a close study of a third Pauline ecclesial term, “koinonia of Spirit,” can clarify the problems of sameness and difference and of the one and the many in Pauline theology. A complex integrity holds to- gether: Israel and the Gentiles; Christ and his church; and the Oneness of God with the divine Lordship of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Paul’s practical problems led to his “trinitar- ian” reflections, suggesting that the relationship between dogmat- ics and practical theology works both ways. Introduction Recent articles by Karen Kilby and Miroslav Volf have reviewed and critiqued what they describe as a growing interest in “social doc- trines of the Trinity.”1 According to Kilby, social theories of the Trin- ity often project our ideals onto God. For “social theorists” God is more appropriately modeled on three human beings than one, yet the three are somehow one, bound together by the divine perichoresis, * A.