BY-GONE GLASGOW Have Been Printed for Sale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Nuclear Physics Conference 2019 29 July – 2 August 2019 Scottish Event Campus, Glasgow, UK

Conference Handbook International Nuclear Physics Conference 2019 29 July – 2 August 2019 Scottish Event Campus, Glasgow, UK http://inpc2019.iopconfs.org Contents Contacts 3 Local organising committee 4 Disclaimer 4 Inclusivity 4 Social media 4 Venue 5 Floor plan 6 Travel 7 Parking 8 Taxis 8 Accommodation 8 Programme 9 Registration 9 Catering 9 Social programme 10 Excursions 11 Outreach programme 13 Exhibition 14 Information for presenters 14 Information for chairs 15 Information for poster presenters 15 On-site amenities 16 General information 17 Health and safety 19 IOP membership 20 1 | Page Sustainability 20 Health and wellbeing 20 Conference app 21 International advisory committee 21 Site plan 23 Campus map 24 2 | Page Contacts Please read this handbook prior to the event as it includes all of the information you will need while on-site at the conference. If you do have any questions or require further information, please contact a member of the IOP conference organising team. General enquiries Claire Garland Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4840 Mobile: +44 (0)7881 923 142 E-mail: [email protected] Programme enquiries Jason Eghan Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4984 Mobile: +44(0)7884 268 232 Email: [email protected] Excursion enquiries Keenda Sisouphanh Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4890 Email: [email protected] Programme enquiries Rebecca Maclaurin Institute of Physics Tel: +44 (0)20 7470 4907 Mobile: +44 (0)7880 525 792 Email: [email protected] Exhibition enquiries Edward Jost IOP Publishing Tel: +44(0)117 930 1026 Email: [email protected] Conference chair Professor David Ireland University of Glasgow 3 | Page The IOP organising team will be onsite for the duration of the event and will be located in Halls 1 and 2 at the conference registration desk. -

Talking Gothic! What Do We Mean by Gothic Architecture and How Can We Identify It?

Talking Gothic! What do we mean by Gothic architecture and how can we identify it? ‘Gothic’ is the name we give to a style of architecture from the Middle Ages. It is usually thought to have begun near Paris in the middle of the 1100s and, from there, it spread throughout Europe and continued into the 16th century. There are many marvellous examples of Gothic buildings throughout Scotland: from Elgin Cathedral in Moray, through amazing buildings like Glasgow Cathedral, Paisley Abbey and Edinburgh St Giles, down to Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. All of these, and more, are well worth a visit! Gothic architecture developed from an earlier style we call Romanesque. Buildings made in the Romanesque style often have rounded arches on their (usually comparatively small) windows and doors, thick columns and walls, lots of ornamental patterns, and shorter structures than the buildings which came later. Dunfermline Abbey is a great example of a Romanesque building in Scotland. The people who paid for the earliest Gothic buildings expressed a wish to transport worshippers to a kind of Heaven on Earth by building higher and brighter churches. What emerged is what we now describe as Gothic. Fashions changed throughout the time that Gothic was the predominant style, and it also varied from place to place. However, the Classical revival made popular as part of the Italian Renaissance largely replaced the Gothic style, and it wasn’t fashionable again until the 19th century. During the Romantic Movement Medieval literature, arts and crafts enjoyed renewed popularity. As a result, Glasgow Cathedral was begun in the Gothic elements can be seen today in the churches, public buildings, and late 12th century and was at the hub of the Medieval city. -

59 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

59 bus time schedule & line map 59 Glasgow View In Website Mode The 59 bus line (Glasgow) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Glasgow: 6:40 AM - 10:15 PM (2) Mosspark: 7:05 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 59 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 59 bus arriving. Direction: Glasgow 59 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Glasgow Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 10:15 AM - 10:15 PM Monday 6:40 AM - 10:15 PM Mosspark Square, Mosspark Ashdale Drive, Glasgow Tuesday 6:40 AM - 10:15 PM Alva Gardens, Mosspark Wednesday 6:40 AM - 10:15 PM Aviemore Road, Mosspark Thursday 6:40 AM - 10:15 PM Friday 6:40 AM - 10:15 PM Mosspark Lane, Mosspark Mosspark Lane, Glasgow Saturday 8:15 AM - 10:15 PM Balerno Drive, Mosspark Ashkirk Drive Northbound, Mosspark 59 bus Info Bellahouston Drive, Mosspark Direction: Glasgow Stops: 33 Auldbar Road, Mosspark Trip Duration: 28 min Line Summary: Mosspark Square, Mosspark, Alva Tanna Drive, Mosspark Gardens, Mosspark, Aviemore Road, Mosspark, Mosspark Lane, Mosspark, Balerno Drive, Mosspark, Mosspark Boulevard, Glasgow Ashkirk Drive Northbound, Mosspark, Bellahouston Mosspark Drive, Mosspark Drive, Mosspark, Auldbar Road, Mosspark, Tanna Drive, Mosspark, Mosspark Drive, Mosspark, Dumbreck Avenue, Dumbreck, Melfort Avenue, Dumbreck Avenue, Dumbreck Dumbreck, Torridon Avenue, Dumbreck, Maxwell Drive, Dumbreck, Nithsdale Road, Dumbreck, Gower Melfort Avenue, Dumbreck Street, Pollokshields, Woodrow Circus, Pollokshields, Dargarvel Avenue, Glasgow Maxwell Grove, -

DENNISTOUN Stop 3 the LADY WELL LIBRARY the Park Opened in 1870 (Category B-Listed) the Lady Well Is on and Was Named After the Library Opened in 1905

Stop 1 ALEXANDRA PARK Stop 2 DENNISTOUN Stop 3 THE LADY WELL LIBRARY The park opened in 1870 (Category B-listed) The Lady Well is on and was named after The Library opened in 1905. It is called a Carnegie the site of an ancient Princess Alexandra. At the Library because it was built using money donated by well that provided entrance is the Andrew Carnegie, a man born in Scotland who water for the people of Cruikshank Fountain. moved to America and became one of the richest Glasgow before it was common to have Look closely at the people who ever lived. He donated money to build running water inside fountain, what kind of over 2000 libraries across the world. The your home. animal do you see on the Dennistoun Library has a special statue which is inside? called the “Dennistoun Angel”. Can you find it? DENNISTOUN Don’t forget to look up! KIDS’ TRAIL Can you draw the well here? Inside the park there is lots to see and do, including ponds, a playground and the beautiful Saracen Fountain which is over 12 metres tall! There are four different statues on the fountain, can you see what they’re holding? Stop 4 BUFFALO BILL Stop 5 WELLPARK BREWERY Stop 6 NECROPOLIS Stop 7 CATHEDRAL (Category A-listed) (Category A-listed) In 1891 Buffalo Bill, One of the most famous and well Wellpark Brewery was first known as the Drygate Glasgow Necropolis Glasgow Cathedral is one of the oldest buildings known figures of the American Old West, brought his Brewery, a brewery is a place where beer is made.It was the first garden in Glasgow and the only mediaeval cathedral in “Wild West Show” to the very spot where his statue is was founded in 1740 by Hugh and Robert Tennent but cemetery in Scotland. -

Gilmorehill Campus Development Framework

80 University Brand & Visual issue 1.0 University Brand & Visual issue 1.0 81 of Glasgow Identity Guidelines of Glasgow Identity Guidelines Our lockup (where and how our marque appears) Our primary lockups Our lockup should be used primarily on Background We have two primary lockups, in line with our primary colour front covers, posters and adverts but not Use the University colour palette, and follow palette. We should always use one of these on core publications, within the inside of any document. the colour palette guidelines, to choose the such as: appropriate lockup for your purpose. For For consistency across our material, and · Annual Review example, if the document is for a specific to ensure our branding is clear and instantly · University’s Strategic Plan college, that college’s colour lockup recognisable, we have created our lockup. · Graduation day brochure. is probably the best one to use. If the This is made up of: document is more general, you may want Background to use a lockup from the primary palette. Our marque/Sub-identity Use a solid background colour – or a 70% Help and advice for compiling our transparent background against full bleed approved lockups are available images (see examples on page 84). from Corporate Communications at Our marque [email protected]. Our marque always sits to the left of the lockup on its own or as part of a sub- identity. 200% x U 200% x U Gilmorehill 200% x U Campus Lockup background. Can be solid or used at 70% transparency Development Framework < > contents | print | close -

Yorkhill 0/1, 30 Nairn Street, Glasgow G3 8SF

Yorkhill 0/1, 30 Nairn Street, Glasgow G3 8SF Ground Floor Flat Yorkhill Offers Over £99,995 Offered to the market in good decorative order, this ideal starter flat occupies a ground floor position within a red sandstone tenement building which is located within walking distance of Glasgow's flourishing West End, Glasgow University and indeed public transport links to Glasgow City Centre and beyond. Internally the accommodation is well laid out and comprises entrance hallway with stripped timber flooring and high level meters, bay windowed lounge with dining recess, double glazed windows, stripped flooring, focal point timber fire place with tiled backing and hearth and shelved storage alcove. The compact galley kitchen offers floor and wall mounted units, has front facing window, integrated oven, hob, hood, washing machine and fridge freezer to be included in the sale price, overhead downlighters and timber flooring. The double bedroom faces the rear of the property and has twin double glazed rear facing windows, storage cupboard housing the Vokera combination boiler for the central heating system and fitted carpet. The bathroom is internal with three piece white suite comprising low level wc, wash-hand basin and panelled bath with Triton mains shower above and tiling around the bath area. Further features include gas central heating, double glazing, security entry system operating the front communal access door, private and enclosed front gardens and enclosed rear gardens where the bin stores and located. Early viewing is strongly recommended as property within this particular area rarely graces the market and indeed tends to sell quickly. The West End of Glasgow is home to the main campus of the University of Glasgow and several major teaching hospitals. -

Open Space Strategy Consultative Draft

GLASGOW OPEN SPACE STRATEGY CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Prepared For: GLASGOW CITY COUNCIL Issue No 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Glasgu: The Dear Green Place 11 3. What should open space be used for? 13 4. What is the current open space resource? 23 5. Place Setting for improved economic and community vitality 35 6. Health and wellbeing 59 7. Creating connections 73 8. Ecological Quality 83 9. Enhancing natural processes and generating resources 93 10. Micro‐Climate Control 119 11. Moving towards delivery 123 Strategic Environmental Assessment Interim Environment Report 131 Appendix 144 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 1. Executive Summary The City of Glasgow has a long tradition in the pursuit of a high quality built environment and public realm, continuing to the present day. This strategy represents the next steps in this tradition by setting out how open space should be planned, created, enhanced and managed in order to meet the priorities for Glasgow for the 21st century. This is not just an open space strategy. It is a cross‐cutting vision for delivering a high quality environment that supports economic vitality, improves the health of Glasgow’s residents, provides opportunities for low carbon movement, builds resilience to climate change, supports ecological networks and encourages community cohesion. This is because, when planned well, open space can provide multiple functions that deliver numerous social, economic and environmental benefits. Realising these benefits should be undertaken in a way that is tailored to the needs of the City. As such, this strategy examines the priorities Glasgow has set out and identifies six cross‐cutting strategic priority themes for how open space can contribute to meeting them. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

Life Expectancy Trends Within Glasgow, 2001-2009

Glasgow: health in a changing city a descriptive study of changes in health, demography, housing, socioeconomic circumstances and environmental factors in Glasgow over the last 20 years Bruce Whyte March 2016 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abbreviations/glossary 3 Executive summary 7 1. Introduction 9 2. Background 10 3. Aims and methods 14 4. An overview of changes in demography, housing, socioeconomic circumstances and environmental factors in Glasgow 17 5. Changes in life expectancy in Glasgow 38 6. Discussion 52 7. Policy implications 57 8. Conclusions 61 Appendices 62 References 65 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Craig Waugh and Lauren Schofield (both of ISD Scotland) who helped produce the GCPH’s local health profiles for Glasgow. Much of the data shown or referred to in this report has been drawn from the profiles. Thank you also to Ruairidh Nixon who summarised trends in key health and social indicators in an internal GCPH report; some of that work is incorporated in this report. I would also like to thank Alan MacGregor (DRS, Glasgow City Council), who provided data on housing tenure, completions and demolitions. I am grateful to my colleagues at the GPCH who have commented on this work as it has developed, in particular, Carol Tannahill, David Walsh, Sara Dodds, Lorna Kelly and Joe Crossland. I would also like to thank Jan Freeke (DRS, Glasgow City Council) who commented on drafts of the report. Members of the GCPH Management Board have also provided useful advice and comments at various stages in the analysis. 3 Abbreviations/glossary Organisations DRS Development and Regeneration Services. -

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts January 2017 Contents Glasgow City Community Health and Care Centre page 1 North East Locality 2 North West Locality 3 South Locality 4 Adult Protection 5 Child Protection 5 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 5 Addictions 6 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 Children and Families 12 Continence Services 15 Dental and Oral Health 16 Dementia 18 Diabetes 19 Dietetics 20 Domestic Abuse 21 Employability 22 Equality 23 Health Improvement 23 Health Centres 25 Hospitals 29 Housing and Homelessness 33 Learning Disabilities 36 Maternity - Family Nurse Partnership 38 Mental Health 39 Psychotherapy 47 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Psychological Trauma Service 47 Money Advice 49 Nursing 50 Older People 52 Occupational Therapy 52 Physiotherapy 53 Podiatry 54 Rehabilitation Services 54 Respiratory Team 55 Sexual Health 56 Rape and Sexual Assault 56 Stop Smoking 57 Volunteering 57 Young People 58 Public Partnership Forum 60 Comments and Complaints 61 Glasgow City Community Health & Care Partnership Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP), Commonwealth House, 32 Albion St, Glasgow G1 1LH. Tel: 0141 287 0499 The Management Team Chief Officer David Williams Chief Officer Finances and Resources Sharon Wearing Chief Officer Planning & Strategy & Chief Social Work Officer Susanne Miller Chief Officer Operations Alex MacKenzie Clincial Director Dr Richard Groden Nurse Director Mari Brannigan Lead Associate Medical Director (Mental Health Services) Dr Michael Smith -

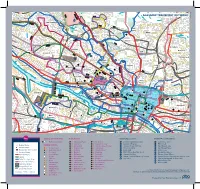

Campus Travel Guide Final 08092016 PRINT READY

Lochfauld V Farm ersion 1.1 27 Forth and 44 Switchback Road Maryhill F C Road 6 Clyde Canal Road Balmore 1 0 GLASGOW TRANSPORT NETWORK 5 , 6 F 61 Acre0 A d Old Blairdardie oa R Drumchapel Summerston ch lo 20 til 23 High Knightswood B irkin e K F 6 a /6A r s de F 15 n R F 8 o Netherton a High d 39 43 Dawsholm 31 Possil Forth and Clyde Canal Milton Cadder Temple Gilshochill a 38 Maryhill 4 / 4 n F e d a s d /4 r a 4 a o F e River Lambhill R B d Kelvin F a Anniesland o 18 F 9 0 R 6 n /6A 1 40 r 6 u F M 30 a b g Springburn ry n h 20 i ill r R Ruchill p Kelvindale S Scotstounhill o a Balornock 41 d Possil G Jordanhill re Park C at 19 15 W es 14 te rn R 17 37 oa Old Balornock 2 d Forth and D um Kelvinside 16 Clyde b North art 11 Canal on Kelvin t Ro Firhill ad 36 ee 5 tr 1 42 Scotstoun Hamiltonhill S Cowlairs Hyndland 0 F F n e 9 Broomhill 6 F ac 0 r Maryhill Road V , a ic 6 S Pa tor Dowanhill d r ia a k D 0 F o S riv A 8 21 Petershill o e R uth 8 F 6 n F /6 G r A a u C 15 rs b R g c o u n Whiteinch a i b r 7 d e Partickhill F 4 p /4 S F a River Kelvin F 9 7 Hillhead 9 0 7 River 18 Craighall Road Port Sighthill Clyde Partick Woodside Forth and F 15 Dundas Clyde 7 Germiston 7 Woodlands Renfrew Road 10 Dob Canal F bie' 1 14 s Loa 16 n 5 River Kelvin 17 1 5 F H il 7 Pointhouse Road li 18 5 R n 1 o g 25A a t o Shieldhall F 77 Garnethill d M 15 n 1 14 M 21, 23 10 M 17 9 6 F 90 15 13 Alexandra Parade 12 0 26 Townhead 9 8 Linthouse 6 3 F Govan 33 16 29 Blyt3hswood New Town F 34, 34a Anderston © The University of Glasgo North Stobcross Street Cardonald -

Old Mines and Mine Masters of the Monklands” British Mining No.45, NMRS, Pp.66-86

BRITISH MINING No.45 MEMOIRS 1992 Skillen, B.S. 1992 “Old Mines and Mine Masters of the Monklands” British Mining No.45, NMRS, pp.66-86. Published by the THE NORTHERN MINE RESEARCH SOCIETY SHEFFIELD U.K. © N.M.R.S. & The Author(s) 1992. ISSN 0309-2199 BRITISH MINING No.45 OLD MINES AND MINES MASTERS OF THE MONKLANDS Brian S. Skillen SYNOPSIS The Monklands lie east of Glasgow, across economically worthwhile coal measures, which have been worked to a great extent. Additionally to coal it proved possible to work a good local ironstone. Mushet’s blackband ironstone proved the resource on which the Monklands rose to prosperity in the 19th century. A pot pourri of minerals was there to be worked and their exploitation may be traced back to the 17th century. Estate feuding provides the first clue to the early coal working of the Monklands. In 1616, Muirhead of Brydanhill was in dispute with Newlands of Kip ps. Such was the animosity of feeling, that the latter turned up at the tiny coal working at Brydanhill and together with his men smashed up Muirhead’s pit head.1 It is likely that Muirhead’s mine had answered purely local needs and certainly if mining did continue it was on this ephemeral basis, at least until the mid 18th century. The reasons are easy to find, fragile local markets that offered no encouragement to invest in mining and a lack of communications that stopped any hope of export. In any case the western markets were then answered by the many small coal pits about the Glasgow district, including satellite workings such as Barrachnie on the western extremity of Old Monkland Parish.