Mimulus Moschatus Dougl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

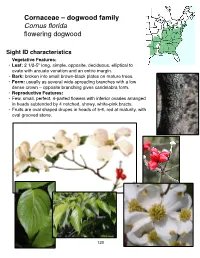

Cornaceae – Dogwood Family Cornus Florida Flowering Dogwood

Cornaceae – dogwood family Cornus florida flowering dogwood Sight ID characteristics Vegetative Features: • Leaf: 2 1/2-5" long, simple, opposite, deciduous, elliptical to ovate with arcuate venation and an entire margin. • Bark: broken into small brown-black plates on mature trees. • Form: usually as several wide-spreading branches with a low dense crown – opposite branching gives candelabra form. • Reproductive Features: • Few, small, perfect, 4-parted flowers with inferior ovaries arranged in heads subtended by 4 notched, showy, white-pink bracts. • Fruits are oval shaped drupes in heads of 5-6, red at maturity, with oval grooved stone. 123 NOTES AND SKETCHES 124 Cornaceae – dogwood family Cornus nuttallii Pacific dogwood Sight ID characteristics Vegetative Features: • Leaf: 2 1/2-4 1/2" long, simple, opposite, deciduous, ovate- elliptical with arcuate venation, margin may be sparsely toothed or entire. • Bark: dark and broken into small plates at maturity. • Form: straight trunk and narrow crown in forested conditions, many-trunked and bushy in open. • Reproductive Features: • Many yellowish-green, small, perfect, 4-parted flowers with inferior ovaries arranged in dense in heads, subtended by 4-7 showy white- pink, petal-like bracts - not notched at the apex. • Fruits are drupes in heads of 30-40, red at maturity and they have smooth stones. 125 NOTES AND SKETCHES 126 Cornaceae – dogwood family Cornus sericea red-osier dogwood Sight ID characteristics Vegetative Features: • Leaf: 2-4" long, simple, opposite, deciduous and somewhat narrow ovate-lanceolate with entire margin. • Twig: bright red, sometimes green splotched with red, white pith. • Bark: red to green with numerous lenticels; later developing larger cracks and splits and turning light brown. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

Mimulus Is an Emerging Model System for the Integration of Ecological and Genomic Studies

Heredity (2008) 100, 220–230 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/hdy SHORT REVIEW Mimulus is an emerging model system for the integration of ecological and genomic studies CA Wu, DB Lowry, AM Cooley, KM Wright, YW Lee and JH Willis Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA The plant genus Mimulus is rapidly emerging as a model direct genetic studies with Mimulus can address a wide system for studies of evolutionary and ecological functional spectrum of ecological and evolutionary questions. In genomics. Mimulus contains a wide array of phenotypic, addition, we present the genomic resources currently ecological and genomic diversity. Numerous studies have available for Mimulus and discuss future directions for proven the experimental tractability of Mimulus in laboratory research. The integration of ecology and genetics with and field studies. Genomic resources currently under bioinformatics and genome technology offers great promise development are making Mimulus an excellent system for for exploring the mechanistic basis of adaptive evolution and determining the genetic and genomic basis of adaptation and the genetics of speciation. speciation. Here, we introduce some of the phenotypic and Heredity (2008) 100, 220–230; doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6801018; genetic diversity in the genus Mimulus and highlight how published online 6 June 2007 Keywords: adaptation; ecological genetics; floral evolution; Mimulus guttatus; Mimulus lewisii; speciation The broad goal of ecological and evolutionary functional Because the expression of such fitness traits can vary genomics (EEFG) is to understand both the evolutionary depending on the environment (for example, Campbell processes that create and maintain genomic and pheno- and Waser, 2001), a comprehensive assessment of the typic diversity within and among natural populations and adaptive significance of these traits also requires the species, and the functional significance of such variation. -

An Updated Checklist of Aquatic Plants of Myanmar and Thailand

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Taxonomic paper An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand Yu Ito†, Anders S. Barfod‡ † University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ‡ Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Corresponding author: Yu Ito ([email protected]) Academic editor: Quentin Groom Received: 04 Nov 2013 | Accepted: 29 Dec 2013 | Published: 06 Jan 2014 Citation: Ito Y, Barfod A (2014) An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand. Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Abstract The flora of Tropical Asia is among the richest in the world, yet the actual diversity is estimated to be much higher than previously reported. Myanmar and Thailand are adjacent countries that together occupy more than the half the area of continental Tropical Asia. This geographic area is diverse ecologically, ranging from cool-temperate to tropical climates, and includes from coast, rainforests and high mountain elevations. An updated checklist of aquatic plants, which includes 78 species in 44 genera from 24 families, are presented based on floristic works. This number includes seven species, that have never been listed in the previous floras and checklists. The species (excluding non-indigenous taxa) were categorized by five geographic groups with the exception of to reflect the rich diversity of the countries' floras. Keywords Aquatic plants, flora, Myanmar, Thailand © Ito Y, Barfod A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Botanischer Garten Der Universität Tübingen

Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen 1974 – 2008 2 System FRANZ OBERWINKLER Emeritus für Spezielle Botanik und Mykologie Ehemaliger Direktor des Botanischen Gartens 2016 2016 zur Erinnerung an LEONHART FUCHS (1501-1566), 450. Todesjahr 40 Jahre Alpenpflanzen-Lehrpfad am Iseler, Oberjoch, ab 1976 20 Jahre Förderkreis Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen, ab 1996 für alle, die im Garten gearbeitet und nachgedacht haben 2 Inhalt Vorwort ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Baupläne und Funktionen der Blüten ......................................................................................... 9 Hierarchie der Taxa .................................................................................................................. 13 Systeme der Bedecktsamer, Magnoliophytina ......................................................................... 15 Das System von ANTOINE-LAURENT DE JUSSIEU ................................................................. 16 Das System von AUGUST EICHLER ....................................................................................... 17 Das System von ADOLF ENGLER .......................................................................................... 19 Das System von ARMEN TAKHTAJAN ................................................................................... 21 Das System nach molekularen Phylogenien ........................................................................ 22 -

Cornus Florida

Cornus florida Family: Cornaceae Flowering Dogwood The genus Cornus contains about 40 species which grow in the northern temperate regions of the world. The name cornus is derived from the Latin name of the type species Cornus mas L., Cornelian-cherry of Europe, from the word for horn (cornu), referring to the hardness of the wood. Cornus alternifolia- Alternate Leaf Dogwood, Blue Dogwood, Green-Osier, Pagoda, Pagoda Cornel, Pagoda Dogwood, Pigeonberry, Purple Dogwood, Umbrella-tree Cornus drummondii-Roughleaf Dogwood, Rough-leaved Dogwood Cornus florida- Arrowwood, Boxwood, Bunchberry, Cornel, Dogwood (used bark to treat dog's mange), False Boxwood, Florida Dogwood, Flowering Dogwood, White Cornel Cornus glabrata-Brown Dogwood, Flowering Dogwood, Mountain Dogwood, Pacific Dogwood, Smooth Dogwood, Western Flowering Dogwood Cornus nuttallii-California Dogwood, Flowering Dogwood, Mountain Dogwood, Pacific Dogwood, Western Dogwood, Western Flowering Dogwood Cornus occidentalis-Western Dogwood Cornus racemosa-Blue-fruit Dogwood, Gray Dogwood, Stiffcornel, Stiff Cornel Dogwood, Stiff Dogwood, Swamp Dogwood Cornus rugosa-Roundleaf Dogwood Cornus sessilis-Blackfruit Dogwood, Miners Dogwood Cornus stolonifera-American Dogwood, California Dogwood, Creek Dogwood, Kinnikinnik, Red Dogwood, Red-Osier Dogwood, Red-panicled Dogwood, Redstem Dogwood, Squawbush, Western Dogwood Cornus stricta-Bluefruit Dogwood, Stiffcornel, Stiffcornel Dogwood, Swamp Dogwood The following is for Flowering Dogwood: Distribution North America, from Maine to New York, Ontario, Michigan, Illinois and Missouri south to Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas east to Florida. The Tree Flowering dogwood is well known for its white flower clusters with large white bracts opening in the spring. The fall foliage is bright red. It is a slow growing tree which attains a height of 40 feet and a diameter of 16 inches. -

Cornus Nuttallii 'Monarch'

http://vdberk.demo-account.nl/trees/cornus-nuttallii-monarch/ Cornaceae Cornus Cornus nuttallii 'Monarch' Height 6 - 8 m Crown wide conical , half-open crown, capricious growing Bark and branches red brown to grey, flaking in small plates Leaf wide ovate to oval, green, 6 - 12 cm Attractive autumn colour yellow, orange, red Flowers green yellow in heads, inconspicuous, bracts white, May Fruits ovoid berry-like stone-fruit, Ø 1 cm, bright red Spines/thorns none Toxicity non-toxic (usually) Soil type humus rich content and moisture-retentive Paving tolerates no paving Winter hardiness 7a (-17,7 to -15,0 °C) Wind resistance moderate Light requirement suitable for shadow Fauna tree valuable for butterflies, provides food for birds Application parks, tree containers, theme parks, cemeteries, roof gardens, large gardens, small gardens, patio gardens Type/shape clearstem tree, feathered tree, specimen shrub Origin A. van der Bom, Oudenbosch (NL), before 1970 This cultivar 'Monarch' has an upright habit with a good upright central leader. Therefore it is better suited as a tree, which distinguishes it from the species. Young twigs are green but turn to brown red quickly. Mature trunks too, are red brown to grey. The green leaf turns yellow to orange red in autumn. The flowers are not showy. However, each head with flowers is surrounded by 6 (sometimes 4 or 8) ovoid, pointed bracts. These turn from cream white to entirely white, sometimes with a pink hue and can become 10 cm. This makes the plant in full bloom very decorative. 'Monarch' flowers profusely. The circa 1 cm large, orange-red fruits appear in early autumn. -

THE JEPSON GLOBE a Newsletter from the Friends of the Jepson Herbarium

THE JEPSON GLOBE A Newsletter from the Friends of The Jepson Herbarium VOLUME 29 NUMBER 1, Spring 2019 Curator’s column: Don Kyhos’s Upcoming changes in the Con- legacy in California botany sortium of California Herbaria By Bruce G. Baldwin By Jason Alexander In early April, my Ph.D. advisor, In January, the Northern California Donald W. Kyhos (UC Davis) turns 90, Botanists Association hosted their 9th fittingly during one of the California Botanical Symposium in Chico, Cali- desert’s most spectacular blooms in fornia. The Consortium of California recent years. Don’s many contributions Herbaria (CCH) was invited to present to desert botany and plant evolution on upcoming changes. The CCH be- in general are well worth celebrating gan as a data aggregator for California here for their critical importance to our vascular plant specimen data and that understanding of the California flora. remains its primary purpose to date. Those old enough to have used Munz’s From 2003 until 2017, the CCH grew A California Flora may recall seeing in size to over 2.2 million specimen re- the abundant references to Raven and cords from 36 institutions. Responding Kyhos’s chromosome numbers, which to requests from participants to display reflect a partnership between Don and specimen data from all groups of plants Peter Raven that yielded a tremendous Rudi Schmid at Antelope Valley Califor- and fungi, from all locations (including body of cytogenetic information about nia Poppy Reserve on 7 April 2003. Photo those outside California), we have de- our native plants. Don’s talents as a by Ray Cranfill. -

Alien Flora of Europe: Species Diversity, Temporal Trends, Geographical Patterns and Research Needs

Preslia 80: 101–149, 2008 101 Alien flora of Europe: species diversity, temporal trends, geographical patterns and research needs Zavlečená flóra Evropy: druhová diverzita, časové trendy, zákonitosti geografického rozšíření a oblasti budoucího výzkumu Philip W. L a m b d o n1,2#, Petr P y š e k3,4*, Corina B a s n o u5, Martin H e j d a3,4, Margari- taArianoutsou6, Franz E s s l7, Vojtěch J a r o š í k4,3, Jan P e r g l3, Marten W i n t e r8, Paulina A n a s t a s i u9, Pavlos A n d r i opoulos6, Ioannis B a z o s6, Giuseppe Brundu10, Laura C e l e s t i - G r a p o w11, Philippe C h a s s o t12, Pinelopi D e l i p e t - rou13, Melanie J o s e f s s o n14, Salit K a r k15, Stefan K l o t z8, Yannis K o k k o r i s6, Ingolf K ü h n8, Hélia M a r c h a n t e16, Irena P e r g l o v á3, Joan P i n o5, Montserrat Vilà17, Andreas Z i k o s6, David R o y1 & Philip E. H u l m e18 1Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Hill of Brathens, Banchory, Aberdeenshire AB31 4BW, Scotland, e-mail; [email protected], [email protected]; 2Kew Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AB, United Kingdom; 3Institute of Bot- any, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; 4Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viničná 7, CZ-128 01 Praha 2, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected]; 5Center for Ecological Research and Forestry Applications, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]; 6University of Athens, Faculty of Biology, Department of Ecology & Systematics, 15784 Athens, Greece, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; 7Federal Environment Agency, Department of Nature Conservation, Spittelauer Lände 5, 1090 Vienna, Austria, e-mail: [email protected]; 8Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ, Department of Community Ecology, Theodor-Lieser- Str. -

Biosystematics of the Mimulus Nanus Complex in Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WAYLAND LEE EZELL for the DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Name) (Degree) in BOTANY presented on August 27, 1970 (Major) (Date) Title: BIOSYSTEMATICS OF THE MIMULUS NANUS COMPLEX IN OREGON Abstract approved:Redacted for Privacy Kenton L. Chambers A biosystematic study was made in seven populations of Mimulus nanus Hook. & Arn. and M. cusickii (Greene) Piper (Scrophulariaceae) in central Oregon, and a taxonomic revision was made of the four species of section Eunanus reported from Oregon--M. nanus, M. cusickii, M. clivicola Greenm. and M. jepsonii Grant.Mimulus nanus and M. cusickii have a chromosome number of n = 8. Based on their distinct genetic and morphological differences, M. nanus, M. cusickii and M. clivicola constitute three separate species in Oregon and surrounding regions. Members of M. nanus are the most highly variable in their morphology and are more widely dis- tributed geographically and ecologically.In a limited area of the Cascade Mountains of central and southern Oregon, an ecotype of M. nanus was discovered which differs from the typical form that is widely distributed in Oregon and Idaho.Also, the populations that have pre- viously been named M. jepsonii, occurring in the southern Cascade and northern Sierra Nevada mountains, Oregon and California, are herein treated as an ecotype of M. nanus; they are morphologically similar to this taxon but show differences in ecology and elevational range. The two ecotypes mentioned above appear to hybridize with typical M. nanus at their zones of contact, thus demonstrating the ability for genetic exchange in nature.Cross-compatibility was confirmed in greenhouse hybridizations between the Cascade ecotype and typical M. -

Native Plant List CITY of OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O

Native Plant List CITY OF OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. Slope Thicket Grass Rocky Wood TREES AND ARBORESCENT SHRUBS Abies grandis Grand Fir X X X X Acer circinatumAS Vine Maple X X X Acer macrophyllum Big-Leaf Maple X X Alnus rubra Red Alder X X X Alnus sinuata Sitka Alder X Arbutus menziesii Madrone X Cornus nuttallii Western Flowering XX Dogwood Cornus sericia ssp. sericea Crataegus douglasii var. Black Hawthorn (wetland XX douglasii form) Crataegus suksdorfii Black Hawthorn (upland XXX XX form) Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash X X Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray Malus fuscaAS Western Crabapple X X X Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa Pine X X Populus balsamifera ssp. Black Cottonwood X X Trichocarpa Populus tremuloides Quaking Aspen X X Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry X X X Prunus virginianaAS Common Chokecherry X X X Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir X X Pyrus (see Malus) Quercus garryana Garry Oak X X X Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara X X X Salix fluviatilisAS Columbia River Willow X X Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow X Salix hookerianaAS Piper's Willow X X Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow X X Salix rigida var. macrogemma Rigid Willow X X Salix scouleriana Scouler Willow X X X Salix sessilifoliaAS Soft-Leafed Willow X X Salix sitchensisAS Sitka Willow X X Salix spp.* Willows Sambucus spp.* Elderberries Spiraea douglasii Douglas's Spiraea Taxus brevifolia Pacific Yew X X X Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar X X X X Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock X X X Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. -

(Linaria Vulgaris) and Dalmatian Toadflax (Linaria

DISSERTATION VIABILITY AND INVASIVE POTENTIAL OF HYBRIDS BETWEEN YELLOW TOADFLAX (LINARIA VULGARIS) AND DALMATIAN TOADFLAX (LINARIA DALMATICA) Submitted by Marie F.S. Turner Department of Soil and Crop Sciences In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2012 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Sarah Ward Christopher Richards David Steingraeber George Beck Sharlene Sing Copyright by Marie Frances Sundem Turner 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT VIABILITY AND INVASIVE POTENTIAL OF HYBRIDS BETWEEN YELLOW TOADFLAX (LINARIA VULGARIS) AND DALMATIAN TOADFLAX (LINARIA DALMATICA) Although outcomes of hybridization are highly variable, it is now considered to play an important role in evolution, speciation, and invasion. Hybridization has recently been confirmed between populations of yellow (or common) toadflax (Linaria vulgaris) and Dalmatian toadflax (Linaria dalmatica) in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States. The presence of hybrid toadflax populations on public lands is of concern, as both parents are aggressive invaders already listed as noxious weeds in multiple western states. A common garden experiment was designed to measure differences in quantitative (shoot length, biomass, flowering stems, seed capsule production) phenological (time of emergence, first flowering and seed maturity) and ecophysiological (photosynthesis, transpiration and water use efficiency (WUE)) traits for yellow and Dalmatian toadflax, F1 and BC1 hybrids, as well as natural field-collected hybrids from two sites. Genotypes were cloned to produce true replicates and the entire common garden was also replicated at two locations (Colorado and Montana); physiological data were collected only in Colorado. All genotypes grew larger and were more reproductively active in Colorado than in Montana, and hybrids outperformed parent taxa across vegetative and reproductive traits indicating heterosis.