Racism, Risk, and the New Color of Dirty Jobs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaiam Vivendi Entertainment and Discovery Communications Release Five New DVD Titles This August

August 1, 2012 Gaiam Vivendi Entertainment And Discovery Communications Release Five New DVD Titles This August NEW YORK, Aug. 1, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- Gaiam Vivendi Entertainment, a leading producer of lifestyle media, announced today the release of five new DVD titles this month under its exclusive home video license agreement with Discovery Communications. The new titles include: Dirty Jobs Collection 8; Deadliest Catch: Inside the Catch; Disaster Collection; Colossal Collection and Voices from the Front. Discovery Channel's Dirty Jobs Collection 8 Gain a new understanding and appreciation for the often-unpleasant jobs others endure to make our everyday life easier, safer and often cleaner. Host Mike Rowe tackles yet another round of the messiest occupations in Dirty Jobs Collection 8 as he introduces viewers to bee removers, septic tank technicians, fish processors and more. With a total run time of 450 minutes, the collection has an SRP of $14.93. Street date: August 7, 2012. Discovery Channel's Deadliest Catch: Inside the Catch From the best brawls to near death experiences, Deadliest Catch: Inside the Catch highlights the most electrifying and jaw-dropping episodes in the series history. Featuring the best of season seven, viewers get a glimpse into the most challenging fishing season on record; including mutiny aboard the ships, fierce arctic storms and the fleet's strategy for survival amongst the open waters. Get ready for another chilly collection from the fishing industry's most revered captains and crew as they take on the harsh, freezing and sometimes deadly job of crab fishing in the arctic. This DVD has a total run time of 220 minutes and an SRP of $14.93. -

Sports Sports

FREE PRESS Page 8 Colby Free Press Monday, August 1, 2005 SSSPORTSPORTS Ready for a clean sweep TV LISTINGS sponsored by the COLBY FREE PRESS WEEKDAYS AUGUST 2 - AUGUST 8 6AM 6:30 7 AM 7:30 8 AM 8:30 9 AM 9:30 10 AM 10:30 11 AM 11:30 KLBY/ABC Good Morning Good Morning America The Jane Pauley The View Million- News Hh Kansas Show aire KSNK/NBC News Cont’d Today Live With Regis Paid Paid Lj and Kelly Program Program KBSL/CBS News Cont’d News The Early Show The 700 Club The Price Is Right The Young and the 1< NX Restless K15CG BBC Yoga Body Caillou Beren. Barney- Sesame Street Dragon Beren. Mister Teletub- d World Electric Bears Friends Tales Bears Rogers bies ESPN SportsCenter SportsCenter Sports- Varied SportsCenter SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live O_ Center Tonight USA Coach Coach Movie Varied Programs P^ TBS Saved Saved Movie Varied Programs Dawson’s Creek Dawson’s Creek Becker Becker P_ by Bell by Bell WGN Chang- Believer Happy Happy Hillbil- Hillbil- Matlock Rockford Files Magnum, P.I. Pa ing Voice Days Days lies lies TNT The Pretender Angel Charmed ER ER Judging Amy QW DSC Paid Paid Paid Paid Varied Programs Surprise by Design Go Ahead, Make QY Program Program Program Program My Dinner A&E Varied Programs Third Watch Varied Programs Investigative City Confidential Q^ Reports HIST Varied Programs Q_ NICK Oddpar- Oddpar- Spon- Spon- Dora the Blue’s Backyar- Dora the Blue’s Lazy- Rugrats Chalk- Rl ents ents geBob geBob Explorer Clues digans Explorer Clues Town Zone DISN Breakfast With Higgly- JoJo’s The Charlie Rolie Koala Doodle- The Higgly- JoJo’s R] Bear town Circus Wiggles & Lola Polie Brothers bops Wiggles town Circus FAM Battle B- Spider- Power Power Two of a Living The 700 Club Gilmore Girls Full Full R_ Daman Man Rangers Rangers Kind the Life House House HALL New Paid The Waltons Dr. -

Country Carpet

PAGE SIX-BFOUR-B TTHURSDAYHURSDAY, ,F AEBRUARYUGUST 23, 2, 20122012 THE LICKING VALLEYALLEY COURIER Stop By Speedy Your Feed Frederick & May Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurnitureCash SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New & Used Furniture & AppliancesCheck Specialists NeedsFrederick With A Line& May Of QUALITY FrigidaireFor All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! 22.6 Cubic Feet Advance QUALITYFEED RefrigerationAppliances. Needs With A iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! $ 00 •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. We hold all customer Regular FOR ALL Remember We 999 •Superior Design and Quality • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends Need Cash? Checks for 30 days! Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FORYOUR ALL ServiceRemember What We We Service Sell! 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control •• All Animal Popular Health Brands Products • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOURFARM $ 00 $379 •• Animal Pet Food Health & Supplies Products •Horse Tack What We Sell! Speedy Cash •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms •• Pet Farm Food & Garden & Supplies Supplies •Horse Tack ANIMALSFARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty •• FarmPlus Ole & GardenYeller Dog Supplies Food Frederick & May Brentny Cantrell •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May 1209 West Main St. No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty Lumber Co., Inc. West Liberty, KY 41472 ALLAN’S TIRE SUPPLY, INC. Lyon(Moved Feed To New Location of West Behind Save•A•Lot)Liberty 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. -

The Authority on Dirt, Grime and All Things Messy Returns

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Bonnary Lek: 240.662.4370 November 15, 2010 [email protected] UPDATED: December 2, 2010 UPDATED: DISCOVERY CHANNEL CELEBRATES THE HOLIDAYS WITH ALL-DAY MARATHONS OF FAN FAVORITES -- World Premiere of 2010 PUNKIN CHUNKIN on Thanksgiving Day at 8PM -- (Silver Spring, Md.) – Discovery fans can get energized this holiday season by tuning in to Discovery Channel on Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s for some of their favorite programming. Starting at 9AM ET/PT on Thanksgiving, there's an all-day marathon of MYTHBUSTERS, the Emmy®-nominated series that uses science to prove or disprove myths and urban legends. Immediately following, at 8PM ET/PT, Discovery Channel will feature the smashing excitement of PUNKIN CHUNKIN, hosted this year by MYTHBUSTERS' Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman. Returning for its third year of high-flying, nail-biting and explosive competition, viewers will watch teams go head to head to launch their pumpkins the furthest. This year marks the 25th anniversary of Delaware's annual “Punkin Chunkin” competition. To see a promo for the 2010 PUNKIN CHUNKIN, go to: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VrS5hhEgz0. Kicking off the Christmas season will be special holiday episodes of MYTHBUSTERS, AMERICAN CHOPPER and DIRTY JOBS WITH MIKE ROWE from Sunday, December 19 to Wednesday, December 22. Then the world premiere of CHRISTMAS UNWRAPPED: HOW STUFF WORKS airs on Thursday, December 23 at 8PM ET/PT, which reveals the amazing science and surprising history behind one of the most celebrated holidays in the United States. Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve will bring viewers the “Best of Discovery” with episodes of popular Discovery series including DEADLIEST CATCH, DIRTY JOBS WITH MIKE ROWE, DUAL SURVIVAL, MAN VS. -

P25tv Layout 1

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 TV PROGRAMS 10:40 Sabrina Secrets Of A 15:05 Milo Murphyʼs Law 07:00 The Loud House 17:30 Seinfeld 15:26 You Have Been Warned 13:45 Doctors Teenage Witch 15:30 Walk The Prank 07:24 Rabbids Invasion 18:00 The New Adventures Of Old 16:14 Mythbusters 14:15 EastEnders 11:05 Hank Zipzer 15:55 Right Now Kapow 07:48 Get Blake Christine 17:02 NASAʼs Unexplained Files 14:45 Death In Paradise 11:30 Alex & Co. 16:25 Supa Strikas 08:12 Harvey Beaks 19:00 Son Of Zorn 17:50 The Big Brain Theory 15:40 Doctor Who 11:55 Disney Mickey Mouse 16:50 Disney11 08:36 Sanjay And Craig 20:00 Wrecked 18:40 Mythbusters 16:35 Stella 00:45 Treehouse Masters 12:00 Rolling With The Ronks 17:15 Mech-X4 00:20 Ice Road Truckers 09:00 Rank The Prank 21:00 Seinfeld 19:30 NASAʼs Unexplained Files 17:25 New Tricks 01:40 Treehouse Masters 12:15 Lolirock 17:40 Gravity Falls 01:10 Pawn Stars 09:24 Henry Danger 22:00 Kevin Can Wait 20:20 How Do They Do It? 18:15 Death In Paradise 02:35 Treehouse Masters 13:05 Star Darlings 18:05 Milo Murphyʼs Law 01:35 Storage Wars 09:48 100 Things To Do Before 23:00 Man Seeking Woman 20:45 Food Factory 20:05 Ripper Street 05:02 Biggest And Baddest 13:10 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug 18:30 Marvelʼs Ant-Man 02:00 Mystery Pickers High School 23:25 Wrecked 21:10 NASAʼs Unexplained Files 21:00 Doctor Foster 05:49 Biggest And Baddest And Cat Noir 18:35 Lab Rats 02:50 Storage Wars 10:12 Game Shakers 22:00 NASAʼs Unexplained Files 06:36 Going Ape 13:35 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug 19:00 Kirby Buckets 03:15 American Pickers 10:36 -

Blue Crime “Shades of Blue” & APPRAISERS MA R.S

FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 9, 2018 5:07:40 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of June 16 - 22, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 6/30/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. Ray Liotta and Jennifer Lopez star in COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS Blue crime “Shades of Blue” & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 15 WATER STREET DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Det. Harlee Santos (Jennifer Lopez, “Lila & Eve,” 2015) and her supervisor, Lt. Matt The LawOffice of Wozniak (Ray Liotta, “Goodfellas,” 1990) will do all that they can to confront Agent STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Robert Stahl (Warren Kole, “Stalker”) and protect their crew, which includes Tess Naza- Auto • Homeowners rio (Drea de Matteo, “The Sopranos”), Marcus Tufo (Hampton Fluker, “Major Crimes”) 978.739.4898 Business • Life Insurance Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com and Carlos Espada (Vincent Laresca, “Graceland”), in the final season of “Shades of 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] Blue,” which premieres Sunday, June 17, on NBC. -

Discovery Channel

Astronaut: NASA Should Cooperate With China in Space : Discovery Space 12/4/08 2:41 PM A Haunting DailyCash CabTV AnimalsScheduleDeadliest Catch WatchArchaeologyWeeklyDestroyed Full in GameEpisodesDinosaursTVSeconds ScheduleDirty Jobs AnimalsCentralWhat'sHuman Hot AnimalHowStuffWorks SignDinosaursInteractiveMost Up WatchedHistoryIditarod DVDsEgyptCentral PuzzleDiscoveryPlanetMan Vs. Earth Wild MythBustersGiftsGlobal Warming CentralNewsSpace PlanetTelescopesHistory Earth QuizDiscoveryTech PrototypeToysPlanet & Earth This! SharksCentralSpace SharkGames Week VideoSpaceDiscovery TechStorm Chasers SurvivormanDownloadsSurvival Zone e-mail share bookmark print WhenTechnologyBehind We the Story:Time Warp Why Left Earth To email this article, type DVDBusterin your friend's name and email address, your name and email Should PlanetCash Cab address, and a message. Then click "submit." EarthDeadliest Friend's name: Catch DVD NASA Friend's email: Dirty Jobs Future Your name: Work Weapons Your email: Human advertisement With Optional Message: Body Iditarod China's Man Vs. submit Wild Space MythBusters VIDEO EXPERTS BLOGS Raw Message Sent! 3 Questions: Space Tourist Fears MORE VIDEO Planet Earth Agency? close Prototype by Leroy Chiao This Shark Week Yahoo! Buzz Storm del.icio.us Chasers Digg Time Warp Mixx When We MySpace Left Earth Newsvine Reddit close Dec 04, A Haunting 3:00 pm Sallie's House http://dsc.discovery.com/space/my-take/china-space-leroy-chiao.html Page 1 of 4 Astronaut: NASA Should Cooperate With China in Space : Discovery Space 12/4/08 2:41 PM 3:00 pm Sallie's House 60 min(s) A young Kansas couple is expecting their first child - but they d Dec 04, Man vs. Wild 4:00 pm Ecuador 60 min(s) Adventurer Bear Grylls demonstrates how to survive in Ecuador's j Dec 04, Cash Cab 5:00 pm Episode 13 Leroy Chiao -- a former NASA astronaut -- was the first American allowed inside the facilities of China's 30 min(s) fledgling space agency. -

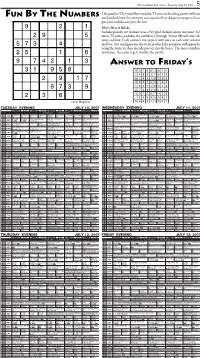

Answer to Friday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, July 10, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRIDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING JULY 10, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING JULY 11, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Mindfreak Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel Dog Bounty Dog Bounty CSI: Miami Peep-show CSI: Miami: Simple Man The Sopranos: Every- (:16) The First 48: Pack of CSI: Miami Peep-show 36 47 A&E (R) (R) (R) (R) (TVPG) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) 36 47 A&E slaying. (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) body Hurts (HD) Lies (TVPG) (R) slaying. -

Discovery Channel September 2013 Program Schedule

Discovery Channel September 2013 Program Schedule For SEA Only 08/31/2013 Bear's Top 25 Moments 06:00 Dirty Jobs With Peter Schmeichel 10:00 Kids Vs. Film Poland Reel Animals 07:00 How It's Made 18 10:30 Gastronuts Wax Figures/awnings/sandwich Crackers/pewter Tankards Can We Eat The Same Food As Animals? 07:30 Factory Made 11:00 Mythbusters 9 Episode 3 Fright Night 08:00 Mythbusters 9 12:00 Swamp Loggers 2 Episode 204 All In 09:00 Beyond Survival With Les Stroud 13:00 Top Hooker Sri Lanka Episode 1 10:00 Think Big 14:00 Amish Mafia Episode 6 Holy War 10:30 Gastronuts 15:00 North America What Would Happen If We Didn't Fart? Outlaws And Skeletons 11:00 How It's Made 18 16:00 Man Vs. Wild 5 Wax Figures/awnings/sandwich Crackers/pewter Tankards Bear's Top 25 Moments 11:30 Factory Made 17:00 Top Hooker Episode 3 Episode 1 12:00 The Devils Ride 2 18:00 Mythbusters 9 Episode 6 Fright Night 13:00 Man Vs. Wild 5 19:00 Brew Masters Bear's Top 25 Moments Bitches Brew 14:00 Mythbusters 9 20:00 Who Framed Jesus? Episode 204 22:00 Man, Woman, Wild 2 15:00 What Happened Next? Louisiana Firestorm Episode 3 23:00 North America 15:30 The Magic Of Science Outlaws And Skeletons Vortex Cannon 09/02/2013 16:00 Brew Masters 00:00 Who Framed Jesus? Bitches Brew 02:00 Top Hooker 17:00 Swamp Loggers 2 Episode 1 All In 03:00 Brew Masters 18:00 The Devils Ride 2 Bitches Brew Episode 6 04:00 Man Vs. -

Discovery Communications and Gaiam to Release Dirty Jobs Collection 6, Paranormal: Haunts and Horrors, and Mythbusters Collection 6 on DVD This September

September 1, 2010 Discovery Communications and Gaiam to Release Dirty Jobs Collection 6, Paranormal: Haunts and Horrors, and MythBusters Collection 6 on DVD This September NEW YORK, Sept. 1 /PRNewswire/ -- Gaiam, Inc., a leading producer of lifestyle media, announced today the release of three new DVD collections, Dirty Jobs Collection 6, Paranormal: Haunts and Horrors, and MythBusters Collection 6, under its exclusive home video license agreement with Discovery Communications. In Dirty Jobs Collection 6, Mike Rowe immerses viewers in his extraordinary quest to meet the men and women behind some of the filthiest, most fascinating jobs on the planet. In this collection, Mike celebrates the people behind the world's toughest jobs, including Animal Control Specialist, in which he is guided by Animal Capture Wildlife Control to skillfully remove a skunk in a residential area. MIKE also learns to breed crickets and remove dead ones in Cricket Farmer and gets a behind-the-scenes look at how reindeer live during the other 364 days when they're not leading Santa's sleigh in Reindeer Farmer! These episodes and much more make for a very entertaining yet grimy Collection 6! This DVD collection carries an SRP of $19.98 on DVD, with a total runtime of 430 minutes.S treet date: September 7, 2010 Enter if you dare into some of the most ghostly gatherings ever documented inP aranormal: Haunts and Horrors. When studying alleged apparitions featured investigators encounter everything from protective poltergeists to destructive demons as they try to unlock the secrets of the dead. You'll watch in frightened awe as a wide variety of techniques document and dissect the evidence of restless souls. -

2 Hurt in Crash, 3A

A1 Charges dropped in dog attack, 2A WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, JUNE 15 & 16, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM 2 hurt in crash, 3A Friday RC championships The SouthSide Raceway in Lake City is currently hosting the 2018 ROAR (Remotely Operated Auto Racers) Fuel 1/8 Off Road Nationals through Sunday, at 1963 SW Bascom Norris Drive. Admission is free to all races this event. Over COREY ARWOOD/Lake City Reporter 300 participants have regis- tered with those taking part hailing from all across the US, Canada, Mexico, Cuba and other places. This is a NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS first time event for Columbia County, which is sponsored locally by the Gateway RC Club. (See story, this page.) Jukebox Oldies at Spirit RC crowd ready to roar This weekend is for dancing at The Spirit of the Suwannee Music Park Racers from as far away as times, speeds and top qualifiers, the scene looked like a miniature in Live Oak. The Jukebox California are in the lineup. NASCAR venue, rather than just Oldies of Valdosta, Ga. people enjoying their favorite will take the stage Friday, By TONY BRITT hobby. while Treble Hook Band [email protected] Brian Lewis, Southside Raceway of Alachua will rock the Hitting the track at full throttle, event coordinator, spent most of the house Saturday. Doors to remote control car racers from day making sure the track had no the Music Hall open at 6 around the world are in Lake City issues and the races were taking p.m. -

800-514-4001 Stay Connected for One Low

PAGE 8B Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan ■ Friday, May 7, 2010 www.yankton.net FRIDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MAY 14, 2010 ARTS 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS From Page 2B Arthur Å WordGirl The Fetch! Cyber- Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Washing- Need to Know (N) McLaugh- Market to Dakota Last of the BBC World Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- America’s Play Like a Girl History PBS (DVS) Å (DVS) Electric With Ruff chase Business Stereo) Å ton Week lin Group Market Å Life “S.D. Summer News Stereo) Å ley (N) Å Heartland of girls basketball in SD. KUSD ^ 8 ^ Company Ruffman Report (N) Å (N) Critters” Wine KTIV $ 4 $ Insider Extra (N) Ellen DeGeneres News (N) News News (N) Ent Friday Night Lights Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å News (N) Jay Leno Late Night Carson News Extra technique relates directly to collage, Deal or Deal or No Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT Two and a Friday Night Lights Dateline NBC (In Stereo) Å KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Jimmy Last Call According Paid Pro- NBC No Deal Deal Å Judy (N) Judy (N) News Å Nightly News Half Men A star player joins the News With Jay Leno (In Fallon (In Stereo) Å With Car- to Jim Å gram relief sculpture and mixed media.