Customized: Automobiles and Advertising Three Decades of Self-Made Automobiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

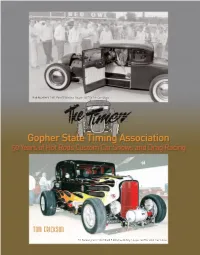

Tom Erickson

Bob Mueller’s 1931 Ford 5 Window Coupe |GSTA’s 1st Car Show Tom Erickson Ed Belkengren’s 1932 Ford 5 Window HiBoy Coupe |GSTA’s 49th Car Show 1951 CHEV............................................................JOHN ORR 1956 1st Annual Entries (partial) 1958 FORD ..............................................MIKE FEESL BOB MCGINLEY ..................................................1935 FORD 1957 FORD..........................................................DAVE LITFIN ERLYN CARLSON ..........................................1952 MERCURY 1957 CHEV ..................................................RICHARD DAME BOYD HARLAN ....................................................1940 OLDS 1954 CHEV ....................................................JAMES WATTS NORM WESP ........................................................1955 OLDS 1955 BUICK................................................BOB TRUCHINSKI GLEN ANDERSON ..................................................ANTIQUE 1946 MERCURY ............................................MAURICEROSSI BOB MUELLER......................................................1931 FORD 1954 FORD ........................................................DAVE BLOW DENNIS DEYO ......................................................1953 FORD GSTA History Queen Contests 1951 DESOTO ................................................JOHN THIELEN DICK COLEMAN ..................................................1956 FORD 1956 CHEV ......................................................DAVID TUFTE AL FEHN ......................................................1950 -

Tom Daniel Grew up in Southern California, a Perfect Place for a Teenager with a Fascination for Cars and the Ability to Draw Th

How many car owners are fortunate enough to have their vehicles featured on a maga- zine cover-much less several in one year? Tom Daniel’s artwork graced three covers in ’65. A wild T-bucket was the single image for the January issue. The June issue shows Tom’s version of a custom Model A woodie. This showstopper would fit in right now as the new millennium woodie. The radical ’32 coupe on September’s cover would be center stage at today’s car show. In the corner of the June ’67 issue is Tom’s rendering of R&C’s "Volksrod" project. One of Tom’s restyling ideas for the new ’67 Camaro was found on the January ’67 cover. Here’s a Daniel rendering that made it to one of street rodding’s most recognizable Track Ts. Tom was given the assignment for the January ’73 issue to design some different Track Ts around an early ‘70s Datsun run- Tom Daniel grew up in Southern ning gear. Their thought was that the over- head fourcylinder powerplant would fit easi- California, a perfect place for a teenager ly under the hood of a street rod T roadster. with a fascination for cars and the ability Well, Tom Prufer liked the drawing so much to draw them. Similar to many young that the nearly duplicated the car, less the fellows, he was always penciling any- fender portion of the original design. where there was an open space—book According to the fanfare in the rod covers, textbook margins, assignment magazines, it remains one of the most papers, and any plain piece of paper he attractive "Trackers" ever built. -

The Automobile and Communication in Twentieth-Century American Literature and Film

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository MOTORCARS AND MAGIC HIGHWAYS: THE AUTOMOBILE AND COMMUNICATION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE AND FILM BY JASON VREDENBURG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English with a minor in Cinema Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee Professor Gordon Hutner, Chair Professor Dale Bauer Professor John Timberman Newcomb Associate Professor José B. Capino ii ABSTRACT Motorcars and Magic Highways examines the nexus between transportation and communication in the development of the automobile across the twentieth century. While early responses to the automobile emphasized its democratizing and liberating potential, the gradual integration of the automobile with communications technologies and networks over the twentieth century helped to organize and regulate automobile use in ways that would advance state and corporate interests. Where the telegraph had separated transportation and communication in the nineteenth century, the automobile’s development reintegrates these functions through developments like the two-way radio, car phones, and community wireless networks. As I demonstrate through a cultural study of literature and film, these new communications technologies contributed to the standardization and regulation of American auto-mobility. Throughout this process, however, authors and filmmakers continued to turn to the automobile as a vehicle of social critique and resistance. Chapter one, “Off the Rails: Potentials of Automobility in Edith Wharton, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis,” establishes the transformative potential that early users saw in the automobile. -

1968 Hot Wheels

1968 - 2003 VEHICLE LIST 1968 Hot Wheels 6459 Power Pad 5850 Hy Gear 6205 Custom Cougar 6460 AMX/2 5851 Miles Ahead 6206 Custom Mustang 6461 Jeep (Grass Hopper) 5853 Red Catchup 6207 Custom T-Bird 6466 Cockney Cab 5854 Hot Rodney 6208 Custom Camaro 6467 Olds 442 1973 Hot Wheels 6209 Silhouette 6469 Fire Chief Cruiser 5880 Double Header 6210 Deora 6471 Evil Weevil 6004 Superfine Turbine 6211 Custom Barracuda 6472 Cord 6007 Sweet 16 6212 Custom Firebird 6499 Boss Hoss Silver Special 6962 Mercedes 280SL 6213 Custom Fleetside 6410 Mongoose Funny Car 6963 Police Cruiser 6214 Ford J-Car 1970 Heavyweights 6964 Red Baron 6215 Custom Corvette 6450 Tow Truck 6965 Prowler 6217 Beatnik Bandit 6451 Ambulance 6966 Paddy Wagon 6218 Custom El Dorado 6452 Cement Mixer 6967 Dune Daddy 6219 Hot Heap 6453 Dump Truck 6968 Alive '55 6220 Custom Volkswagen Cheetah 6454 Fire Engine 6969 Snake 1969 Hot Wheels 6455 Moving Van 6970 Mongoose 6216 Python 1970 Rrrumblers 6971 Street Snorter 6250 Classic '32 Ford Vicky 6010 Road Hog 6972 Porsche 917 6251 Classic '31 Ford Woody 6011 High Tailer 6973 Ferrari 213P 6252 Classic '57 Bird 6031 Mean Machine 6974 Sand Witch 6253 Classic '36 Ford Coupe 6032 Rip Snorter 6975 Double Vision 6254 Lolo GT 70 6048 3-Squealer 6976 Buzz Off 6255 Mclaren MGA 6049 Torque Chop 6977 Zploder 6256 Chapparral 2G 1971 Hot Wheels 6978 Mercedes C111 6257 Ford MK IV 5953 Snake II 6979 Hiway Robber 6258 Twinmill 5954 Mongoose II 6980 Ice T 6259 Turbofire 5951 Snake Rail Dragster 6981 Odd Job 6260 Torero 5952 Mongoose Rail Dragster 6982 Show-off -

TMPCC MEDIAMEDIA RADIO, TELEVISION & PRINT REPORTING the 2014 GRAND NATIONAL ROADSTER SHOW Written and Photographed By: Ken Latka

TMPCCTMPCC MEDIAMEDIA RADIO, TELEVISION & PRINT REPORTING THE 2014 GRAND NATIONAL ROADSTER SHOW Written and photographed by: Ken Latka The Grand National Roadster Show is the longest running indoor car show in the world. It is also one of the most respected car shows in the United States. There are 500 roadsters, customs, hot rods and motorcycles filling eight buildings at the Fairplex in Pomona, California, all vying for top awards, including one of the most coveted honors in the custom car building world, being named “America’s Most Beautiful Roadster”. The first show was organized by Al Slonaker in 1949 and it ran for 54 years in various cities in Northern California. Originally called “The Oakland Roadster Show”, the show has since changed it’s name to “The Grand National Roadster Show”. The GNRS moved to Pomona in 2004 and this is fitting, because many Wes Rydell’s 1935 Chevrolet Phaeton “Black Bowtie” consider Southern California the birthplace of hot rodding. Now in its 65th year, this truly is “The Grand Daddy of all Roadster Shows”. The GNRS attracts the best designers, builders and of course, thousands of eager spectators from all over the world who are ready to take in the sights and sounds of the event. John Buck of Rod Shows has been organizing the event for some years now, and I can tell you that the GNRS never disappoints. The GNRS is a hot rod and custom car lovers dream and the competition at this level has produced some famous and radical customs, including Silhouette and Ed Roth's Mysterion. -

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019 The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | Friday April 26 and Saturday April 27, 2019 10am BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS 580 Madison Avenue Rupert Banner +1 (212) 644 9001 New York, New York 10022 +1 (917) 340 9652 +1 (212) 644 9009 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90046 Evan Ide From April 23 to 29, to reach us at +1 (917) 340 4657 the Tupelo Automobile Museum: 220 San Bruno Avenue [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6514 San Francisco, California 94103 +1 (212) 644 9009 John Neville +1 (917) 206 1625 bonhams.com/tupelo To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] bonhams.com/tupelo PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION Eric Minoff The Tupelo Automobile Museum +1 (917) 206-1630 Please see pages 4 to 5 and 223 to 225 for 1 Otis Boulevard [email protected] bidder information including Conditions Tupelo, Mississippi 38804 of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Automobilia PREVIEW Toby Wilson AUTOMATED RESULTS SERVICE Thursday April 25 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 8700 273 619 +1 (800) 223 2854 Friday April 26 [email protected] Automobilia 9am - 10am FRONT COVER Motorcars 9am - 6pm General Information Lot 450 Saturday April 27 Gregory Coe Motorcars 9am - 10am +1 (212) 461 6514 BACK COVER [email protected] Lot 465 AUCTION TIMES Friday April 26 Automobilia 10am Gordan Mandich +1 (323) 436 5412 Saturday April 27 Motorcars 10am [email protected] 25593 AUCTION NUMBER: Vehicle Documents Automobilia Lots 1 – 331 Stanley Tam Motorcars Lots 401 – 573 +1 (415) 503 3322 +1 (415) 391 4040 Fax ADMISSION TO PREVIEW AND AUCTION [email protected] Bonhams’ admission fees are listed in the Buyer information section of this catalog on pages 4 and 5. -

Kustom Kulture Von Dutch, Ed Big Daddy Roth, Robert Williams and Others 1St Edition Download Free

KUSTOM KULTURE VON DUTCH, ED BIG DADDY ROTH, ROBERT WILLIAMS AND OTHERS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE C R Stecyk | 9780867194050 | | | | | Kustom Kulture: Von Dutch, Ed "Big Daddy" Roth, Robert Williams and Others He was fearless. It was at this time that the lowbrow art movement began to take on steam. Readers also enjoyed. Ed Roth and the late "Von Dutch" have had a growing following for the past 45 years. Ed Roth and the late "Von Dutch" have had a growing following for the past 45 years. Eventually Roth gained the upper hand and "just started to beat the living crap out of the guy". His brother Gordon also became a Latter-day Saint. The Dutch Institute. Brucker said that Roth was very loyal and a very hard worker, even though he was not making much money. William Faulkner Paperback Books. Edwin Vazquez marked it as to-read Jan 14, William Shakespeare Paperback Books. Mainstream motorcycle magazines refused to run his articles and ads, so he started his own publication called ChoppersEd Big Daddy Roth featured articles on extending forks, custom sissy bars, etc. His mix of California car culture, cinematic apocalypticism, and film noir helped to create a new genre of psychedelic imagery. Dutch Kustom Kulture Von Dutch. After this incident, Roth burned his biker posters, leaving the lifestyle behind. Namespaces Article Talk. Home 1 Books 2. One of Roth's personal drivers was a tangerine orange Chevy 2-door post with a Ford cu. Tennessee Williams Paperback Books. Tom Luca rated it really liked it Dec 20, Skip to main content. -

Introduction to R&C Database Compilation & Index

Introduction to R&C Database Compilation & Index I have a long history and fondness for Rod & Custom magazine. This is the first magazine I purchased at age 10, and I’ve been hooked ever since. I often refer back to my collection, but find it hard to quickly lay my hands on a given article. This is for fellow HAMB members who share a love for this little magazine. This Index covers Rod & Custom Magazine from May 1953 through May 1974. I stopped at 1974 since R&C went out of print then. R&C was restarted in December 1988 and lasted until October 2014. This index is created for general reference, technical reference, research, tracing automobile histories, and genealogy. I have attempted to use a consistent categorization or article grouping scheme across all 20+ years, even though editors or previous compilations may not have used this convention. This index contains the following specific information: Title of each article along with a descriptive supplement such as club affiliation, noted customizers, past owners, professions, etc. The author’s and/or photographer’s name where space allowed. Featured vehicle year, make, model, & engine and/or engine displacement where available or where space allowed. Vehicle owner name, city and state. Where the country is other than the United States, I listed the country Product manufacturer name, city and state. Address may be included if space allowed. The month and page number of each feature article or photograph. The index is sorted by year, and a title at the top of each page indicates which year. -

Ford Model T Kits Through the Years More Than a Dozen Different Configurations Possible

AMT’s Double T kit included parts for two complete mod- els, a stock T road- ster and a chopped coupe hot rod. It was also possible to build the hot rod as a roadster. AMT produced several promotional kits for the Ford Motor Company in 1964 and ’65. The ’65 edition of the AMT Double T eliminated the AMT has produced a chopped coupe in favor of a stock “phone booth” coupe body. That kit number of different T was rereleased as part of the company’s Street Rods series. Rick kits over the years. Hanmore backdated this kit to reflect hot rod trends in the early ’60s. The company’s first was the 1960 edition im e Latham supercharger. The kit contained two complete models, a of the Double T with “T”T stock roadster/pickup and a chopped coupe. Nearly 200 parts made the chopped coupe Ford Model T kits through the years more than a dozen different configurations possible. It was a great kit, option. Subsequent and though it may seem dated now, it’s still one of the nicest vintage kits included the ’27 Ford kits. phaeton and fire by TERRY JESSEE Later versions of the kit included a tall, unchopped coupe, a police engine, and a paddy wagon, and a fruit wagon. In all cases, the kit still provided parts retooled ’23 road- -BUC K E T . Th a t ’ s one of those immortal hot rod The Ford Model T topped many “Car of the Century” for two complete models – one stock and one street rod. -

Showbizshowbiz ER CAR SL C Y L R U H B

ER CAR SL C Y L R U H B C O F A I S L O A U R TH AUST Adelaide’s Largest Chrysler, Jeep & Dodge Dealer FOR THE DRIVEN. FOR THE DRIVEN CHRYSLER 300 Introducing the reborn Chrysler 300. With a bold new face, smooth handling and a luxurious interior with 7-airbags, a reverse camera and an 8.4-inch colour touchscreen, travel life’s journey in style and comfort. The Chrysler 300 isn’t just for anyone. It’s for the driven. Discover more at adrianbrienjeep.com.au Corner of 1305 South Rd & 1 Ayliffes Road, ST MARYS Phone 8374 5444 Rick McLoughlin - 0400 273 699 | Alan Anderson - 0451 972 212 adrianbrienjeep.com.au LVD173. Chrysler is a registered trademark of FCA US LLC. AB1094 ShowbizShowbiz ER CAR SL C Y L R U H B C O F A I S L O october 2O17 - february 2o18 U A T TR H AUS General monthly meetings are held on the FIRST Tuesday of every month at: The West Adelaide Football Club, 57 Milner Rd, Richmond. President Iain Carlin Vice President Andrew Ingleton Secretary Di Hastwell Treasurer Greg Helbig Events Coordinator Damian Tripodi ACF Coordinator Jason Rowley Events Organisers John Leach Chris Taylor Historic Registrar Stuart Croser Inspectors North John Eckermann Jason Rowley South Chris Hastwell Charles Lee Central Rob McBride Dave Hocking Sponsorship & Marketing Evan Lloyd Club Library Iain Carlin Editorial / Design Dave Heinrich Webmasters Iain Carlin Dave Heinrich Photography Lesley Little Zoran Kanti-Paul Hiskia Adi Putra Alan Smart John Antinow Mary Heath David Rawnsley Damian Tripodi Andy Miller Luke Balzan Bruce England Andrew Lax Ingrid Matschke Contributors Zoran Kanti-Paul Hiskia Adi Putra Buddy Fadillah Danny Caiazza Luke Balzan John Antinow Tim White Geoff Pine Rod Taylor Paul Cronin Ron Neighbour Regular - $40.00 per year (& quarterly magazine) Marg Neighbour Historic Registration - $50 per year (& quarterly magazine) Source Street Machine Hot Rod DISCLAIMER Mopar Muscle ® The Distributor Chrysler, Jeep , Dodge and Mopar are registered trademarks of FCA LLC and are used with permission by the Chrysler Car Club of South Australia. -

2018.3.16 Axel Backlund Ba in Fine Arts; Fashion Design Degree Work

2018.3.16 AXEL BACKLUND BA IN FINE ARTS; FASHION DESIGN DEGREE WORK 1. Abstract 1. Abstract 6. Result 1.1 Keywords 6.1 Outft 1 6.2 Outft 2 2. Background 6.3 Outft 3 2.1 Defnition of Raggare 6.4 Outft 4 2.2 History of Raggare 6.5 Outft 5 2.3 Similar Subcultures 6.6 Outft 6 2.4 Car Culture 6.7 Outft 7 2.4.1 Hot Rods 6.8 Outft 8 2.4.2 Pilsnerbil 2.5 Action Painting 7. Tech Pack 2.5.1 McQueen 7.1 Outft 1 2.6 Graffti and Street Art In this project a collection of clothes, based on the raggar culture has been developed. Te work is intended to be 7.2 Outft 3 2.7 Airbrush 7.3 Outft 5 a modernization of the clothing, exploring the subculture and developing it, however without loosing its attitude. 2.7.1 “The Shirt Kings” Infuences from other related subcultures have also taken part in the work. 7.4 Outft 8 3. Motive Te aim is to investigate the technique of spray painting directly on garments, as a method for developing prints, 8. Discussion taking visual inspiration from the culture of raggare. Sources for inspiration to the painting have been grafti, 3.1 State of the Art airbrush and action painters. In order to keep the attitude of the raggar culture, the collection is largely based 3.1.1 Graffti in Fashion on vintage clothing, linked to the culture in question. Te result in this project is a collection containing eight 3.1.2 Reworking Vintage Garments 9. -

F16 Art Titles - August 2016 Page 1

Art Titles Fall 2016 {IPG} Death and Memory Soane and the Architecture of Legacy Helen Dorey, Tom Drysdale, Susan Palmer, Frances S... Summary This book of essays is published to coincide with an exhibition of the same title at Sir John Soane's Museum, Lincoln's Inn Fields, London (October 23, 2015–March 26, 2016) commemorating the 200th anniversary of Soane's beloved wife Eliza's death on November 22, 1815. Its relevance to Soane studies, is, however, much broader, with essays shedding new light on the architecture of legacy in Sir John Soane's Museum; Soane's preoccupation with memorialization as revealed in the design process for the Soane family tomb; the legacy of his drawings collection; and Soane's Pimpernel Press attempt shortly before his death to sustain future interest in his collections by creating a series of 9780993204111 time capsules. The essays, written by the curatorial team at Sir John Soane's Museum, are Pub Date: 9/28/16 accompanied by 39 illustrations in full color, some of them published for the first time. Ship Date: 9/28/16 $16.95/$33.95 Can. Contributor Bio Discount Code: LON Trade Paperback Helen Dorey is Deputy Director and Inspectress of Sir John Soane’s Museum. Tom Drysdale was the Museum's Soane Drawings Cataloguer and now works for Historic Royal Palaces. Susan Palmer is 48 Pages Archivist and Head of Library Services at Sir John Soane's Museum. Dr. Frances Sands is Catalogue Carton Qty: 70 Editor of the Adam Drawings Project, Sir John Soane's Museum. Architecture / Historic Preservation ARC014000 11 in H | 8.5 in W | 0.2 in T | 0.6 lb Wt A Whakapapa of Tradition One Hundred Years of Ngato Porou Carving, 1830-1930 Ngarino Ellis, Natalie Robertson Summary From the emergence of the chapel and the wharenui in the nineteenth century to the rejuvenation of carving by Apirana Ngata in the 1920s, Maori carving went through a rapid evolution from 1830 to 1930.