Saints of Sindh by Peter Mayne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Drama of Saintly Devotion Performing Ecstasy and Status at the Shaam-E-Qalandar Festival in Pakistan Amen Jaffer

A Drama of Saintly Devotion Performing Ecstasy and Status at the Shaam-e-Qalandar Festival in Pakistan Amen Jaffer Figure 1. Dancing the dhama\l in Sehwan in front of Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb, 7 February 2011. (Photo by Saad Hassan Khan) On the evening of 16 February 2017, the dhamal\ 1 ritual at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan, Pakistan, was tragically cut short when a powerful bomb ripped through a crowd of devotees, killing 83 and injuring hundreds (Khan and Akbar 2017).2 Seven years prior, in January 2010, I was witness to another dhama\l performance in the same courtyard of this 13th- century Sufi saint’s shrine (fig. 2). On that evening, the courtyard, which faces Qalandar’s tomb, 1. Dhama\l is a ritualized expression of love, desire, and connection with a saint as well as a celebration of the saint’s powers and miracles. It can take the form of dance or music. For treatments of the ritual sensibilities of this genre see Frembgen (2012) and Abbas (2002:33–35). For an analysis of its musical form and style see Wolf (2006). 2. Sehwan is a small city in the southeast province of Sindh that is best known as the site for Shahbaz Qalandar’s tomb and shrine. TDR: The Drama Review 62:4 (T240) Winter 2018. ©2018 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 23 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram_a_00791 by guest on 24 September 2021 was also crowded with human bodies — but those bodies were very much alive. -

Filmmakers' Biography Filming 'Shahbaz Qalandar': From

Issue 2 I 2020 Filmmakers’ Biography Hasan Ali Khan Hasan Ali Khan is Assistant Professor at Habib and University, Karachi. A historian of religion, he completed Aliya Iqbal-Naqvi his Ph.D. from SOAS in 2009 and has published extensively on medieval Sufi orders, the Hindu community Karachi of Sindh, contemporary Sufi practices in Pakistan, the Qadiriyya Order in Istanbul, and the city of Sehwan. He also works with film and visual ethnography. Aliya Iqbal-Naqvi is faculty of Social Sciences and Liberal Arts at I.B.A., Karachi. Her areas of expertise are Islamic intellectual history and South Asian history. She holds a Master’s degree from Harvard University and is working towards a Ph.D. Filming ‘Shahbaz Qalandar’: From Spectacle to Meaning Introduction Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, the ‘Red Falcon,’ God’s beloved friend, is the pulsing heart of Sehwan, a small town in Sindh, 300 km north of Karachi. Known in common parlance as Sehwan Sharif (‘Revered Sehwan’), the life of the town revolves around the shrine of the Qalandari Sufi Saint Syed Muhammad Usman Marwandi (d. 1274) or Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. Sehwan is the last remaining center of the Qalandariyya Sufi order in the world today. Attracting over 5 million pilgrims a year, Sehwan is not only one of the most visited and venerated sacred geographies in South Asia, but it is also Shahbaz Qalandar 37 arguably one of the most uniquely vibrant. Often characterized in popular discourse as ‘the greatest party on earth,’1 the shrine culture's very uniqueness and vibrancy have served to obscure the core realities of the Qalandariyya spiritual path integral to the ritual at Sehwan. -

Budget Execution Report 2Nd QUARTER 2020-21

Budget Execution Report 2nd QUARTER 2020-21 31th December, 2020 Government of Sindh Finance Department Table of contents: Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Table 1 Interim Fiscal Statement .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Table 2 Revenue by Object .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 3 Revenue by Department........................................................................................................................................... 7 Table 4 Expenditure by Department .................................................................................................................................... 9 Table 5 Recurrent Expenditure by Department, Grant and Object ............................................................................... 20 Table 6 Provincial ADP by Sector and Sub-sector .......................................................................................................... 41 Table 7 Development Expenditure by Sector, Subsector and Scheme ....................................................................... 42 Table 8 Current Capital Expenditure ............................................................................................................................... -

Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No

FINAL REPORT Mid-Term Evaluation /' " / " kku / Kondioro k I;sDDHH1 (Koo1,, * Nowbshoh On$ Hyderobcd Bulei Pt.ochi 7 godin Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No. 391-0480 Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development Islamabad, Pakistan IOC PDC-0249-1-00-0019-00 * Delivery Order No. 23 prepared by DE LEUWx CATHER INTERNATIONAL LIMITED May 26, 1993 Table of Contents Section Pafle Title Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables and Figures iv List of Abbieviations, Acronyms vi Basic Project Identification Data Sheet ix AID Evaluation Summary x Chapter 1 - Introduction 1-1 Chapter 2 - Background 2-1 Chapter 3 - Road Maintenance 3-1 Chapter 4 - Road Rehabilitation 4-1 Chapter 5 - Training Programs 5-1 Chapter 6 - District Revenue Sources 6-1 Appendices: - A. Work Plan for Mid-term Evaluation A-1 - B. Principal Officers Interviewed B-1 - C. Bibliography of Documents C-1 - D. Comparison of Resources and Outputs for Maintenance of District Roads in Sindh D-1 - E. Paved Road System Inventories: 6/89 & 4/93 E-1 - F. Cost Benefit Evaluations - Districts F-1 - ii Appendices (cont'd.): - G. "RRM" Road Rehabilitation Projects in SINDH PROVINCE: F.Y.'s 1989-90; 1991-92; 1992-93 G-1 - H. Proposed Training Schedule for Initial Phase of CCSC Contract (1989 - 1991) H-1 - 1. Maintenance Manual for District Roads in Sindh - (Revised) August 1992 I-1 - J. Model Maintenance Contract for District Roads in Sindh - August 1992 J-1 - K. Sindh Local Government and Rural Development Academy (SLGRDA) - Tandojam K-1 - L. -

PMD # Amount Date Name of Sponsors Amount Date Name of Scheme Cost Expenditure Savings % Utilization 1 357 100 9/25/2012 Dr

PM Directives Funds Released Sr. # Executing Agency Detail of Scheme Approved / Executed Under PMDs Financial Progress Name of PMD # Amount Date Amount Date Name of Scheme Cost Expenditure Savings sponsors % Utilization 1 402 200 10/16/2012 Dr. Fahmida Highway Division Badin 50 10/30/2012 Construction of Golarchi by pass road 289.864 187.545 0 64.7 Urban water supply scheme Shaheed Fazal 67.3 2 221 50 9/17/2012 Dr. Fahmida XEN PHE Division Badin 200 12/17/2012 90.127 60.652 14.348 Mirza, MNA Rahu Golarchi 50.6 Urban drainage Scheme Shaheed Fazal Rahu 107.85 54.58 10.42 Improvent & extention of Rural water supply 38.9 15.367 5.984 9.383 scheme Lawari Sharif 3 785 50 1/8/2013 Ghulam Ali DG Rural Development Department 50 2/14/2013 5.3 Construction of CC block in Mosque Qadir 4 0.21 3.79 Nizamani, Bux Colony District Badin MNA Construction of CC block at village Andhani 5.3 4 0.21 3.79 Nizamani district Badin Construction of CC block at village jaffar khan 100.0 4 4 0 chandio Reconditioning of metallic road Dargha 53.7 4 2.148 1.852 Jumman shah Construction of metallic road for Dargha 55.0 1.187 0.653 0.534 bukhair to zafarabad Construction of metallic road for village Kazi 49.2 10.377 5.102 5.275 Ibrahim 52.3 At village Dewani faqeer to Ghulam shah road 2.505 1.311 1.194 Village Pir Bux chandio 1.398 1.387 0.011 99.2 In village Ali Akber Paryal 1.398 1.398 0 100.0 Village Allahdino jamali 1.398 1.398 0 100.0 Village Urs Rahimoon 1.398 1.18 0.218 84.4 Village haji allah warayo 1.398 1.179 0.219 84.3 Village allahdino Notkani 1.398 1.398 -

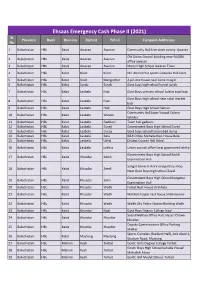

UPDATED CAMPSITES LIST for EECP PHASE-2.Xlsx

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Phase II (2021) Sr. Province Bank Division Distrcit Tehsil Campsite Addresses No. 1 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Community Hall Live stock colony Awaran Old Union Council building near NADRA 2 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran office awaran 3 Balochistan HBL Kalat Awaran Awaran Model High School Awaran Town 4 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Kalat Mir Ahmed Yar sports Complex Hall kalat 5 Balochistan HBL Kalat Kalat Mangochar A private house near Jame masjid 6 Balochistan HBL Kalat Surab Surab Govt boys high school hostel surab 7 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys primary school Adalat road hub Govt Boys high school near sabzi market 8 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub hub 9 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Hub Govt Boys High School Sakran Community Hall Jaam Yousuf Colony 10 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Winder Winder 11 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Gaddani Town hall gaddani 12 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Government Boys High School Dureji 13 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Dureji Govt boys school hasanabad dureji 14 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Bela B&R Office Mohalla Rest House Bela 15 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Uthal District Council Hall Uthal 16 Balochistan HBL Kalat Lasbela Lakhra Union council office local goverment lakhra Government Boys High School Karkh 17 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Karkh Examination Hall Sangat General store and poltary shop 18 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zeedi Near Govt Boys high school Zeedi Government Boys High School Norgama 19 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Zehri Examination Hall 20 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Forest Rest House Drakhala 21 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Mohbat Faqeer rest house Shahnoorani 22 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Wadh Wadh City Police Station Building Wadh 23 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Naal Govt Boys Degree College Naal Social Welfare Office Hall, Hazari Chowk 24 Balochistan HBL Kalat Khuzdar Khuzdar khuzdar. -

Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated List of Campsites and Bank Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments Campsites Ehsaas Emergency Cash List of campsites for biometrically enabled payments in all 4 provinces including GB, AJK and Islamabad AZAD JAMMU & KASHMIR SR# District Name Tehsil Campsite 1 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 2 Bagh Bagh Boys High School Bagh 3 Bagh Bagh Boys inter college Rera Dhulli Bagh 4 Bagh Harighal BISP Tehsil Office Harigal 5 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 6 Bagh Dhirkot Boys Degree College Dhirkot 7 Hattain Hattian Girls Degree Collage Hattain 8 Hattain Hattian Boys High School Chakothi 9 Hattain Chakar Boys Middle School Chakar 10 Hattain Leepa Girls Degree Collage Leepa (Nakot) 11 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 12 Haveli Kahuta Boys Degree Collage Kahutta 13 Haveli Khurshidabad Boys Inter Collage Khurshidabad 14 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Post Graduate College Kotli 15 Kotli Kotli Inter Science College Gulhar 16 Kotli Kotli Govt. Girls High School No. 02 Kotli 17 Kotli Kotli Boys Pilot High School Kotli 18 Kotli Kotli Govt. Boys Middle School Tatta Pani 19 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Girls High School Sehnsa 20 Kotli Sehnsa Govt. Boys High School Sehnsa 21 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Govt. Boys Degree College Fatehpur Thakyala 22 Kotli Fatehpur Thakyala Local Govt. Office 23 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Charhoi 24 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Middle School Gulpur 25 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys Higher Secondary School Rajdhani 26 Kotli Charhoi Govt. Boys High School Naar 27 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Boys High School Khuiratta 28 Kotli Khuiratta Govt. Girls High School Khuiratta 29 Bhimber Bhimber Govt. -

Pakistan, First Quarter 2018

PAKISTAN, FIRST QUARTER 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Updated 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 20 December 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; China/India border status: CIA, 2006; Kashmir border status: CIA, 2004; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, November 2015a; Natural Earth, undated; incident data: ACLED, 15 December 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 PAKISTAN, FIRST QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - UPDATED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 20 DECEMBER 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Riots/protests 1266 2 3 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 68 48 133 Development of conflict incidents from March 2016 to March 2018 2 Remote violence 37 17 33 Violence against civilians 22 12 18 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 16 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Total 1409 79 187 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 15 December 2018). Localization of conflict incidents 4 Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from March 2016 to March 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 15 December 2018). 2 PAKISTAN, FIRST QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - UPDATED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 20 DECEMBER 2018 Methodology Geographic map data is primarily based on GADM, complemented with other sources if necessary. -

MIFS Newsletter N°2 2009

MI French Interdisciplinary Mission in Sindh FS Fieldwork in a sensitive context In the last IIAS issue devoted to Pakistan, Kristoffel Lieten article was entitled: “Pakistan, an abundance of problems and scant knowledge”. He followed Stephen Cohen who claimed in 2004 that, the USA has “only a few true Pakistan experts and knows remarkably little about the country. Much of what has been written is palpably wrong, or at best superficial” (IIAS Newsletter 49, Autumn 2008, p. 3). For instance, one of the most neglected aspects regarding Pakistan 9 is the segmentation of the country and its society. However by segmentation, we do not mean that the country is about to be dismembered, contrary to common 0 assumptions by so-called experts. 0 We claim that the spread of radical Islam is mainly a response to social problems that depend on the history and the structure of local societies. Islamist groups tend to focus naturally on places where there is a lack of social cohesiveness and more particularly on places where the State fails to interact with local society. y 2 But then we can ask why some areas in Pakistan seem to be spared by the r influence of radical Islam, as it is the case of Sindh (Karachi excluded)? Even though social injustice and violence are found there, based on tribal, ethnic or a religious differences, the province of Sindh is an interesting case study. During our latest field trip in Sehwan Sharif, a major pilgrimage centre in contemporary u Pakistan, we observed that the “Sufi system” produces a certain form of social cohesiveness. -

List of Institutes Where Diploma in Commerce Is Being Offered

LIST OF INSTITUTES WHERE DIPLOMA IN COMMERCE IS BEING OFFERED 1. Banking with Computer 2. Accounts with Computer 3. Office Secretarial Practicewith English Shorthand &Typing (ES&T) 4. Insurance with Computer 5. Salesmanship with Computer S.# Region Name Of Institutions Address 1 GIB & CE, Azizabad Azizabad No. 2, Karachi 2 GIB & CE, Gulistan-e-Jauhar Block-12, Near Telephone Exchange, Gulistan-e-Jauhar, Karachi Karachi 3 GIB & CE, Lyari Plot No. 2593, Rangiwara, Lyari, Karachi 4 GIB & CE, Malir Saudabad, Near Urdu Nagar, Malir, Karachi 5 GIB & CE, Orangi Town Sector 11 1/2 Orangi Town, Karachi 1 GIB & CE, Digri Govt. Boys High School Digri 2 GIB & CE, Mirpurkhas Sattelite Town Mirpurkhas 3 GIB & CE, Khipro Near Sanghar Bye pass Khipro 4 Mirpurkhas GIB & CE, Sanghar Bakhoro Road Sanghar 5 GIB & CE, Tando Adam Near Bye Pass Tando Adam 6 GIB & CE, Mithi Near Al Mehdi Hospital, Naukot Road, Mithi 7 GIB & CE, Umerkot Near Grid Station Mirpurkhas Road Umerkot 1 GIB & CE, Jacobabad Near Shahbaz Air Base, Jacobabad 2 GIB & CE, Mirokhan Near Taluka Hospital, Mirokhan 3 GIB & CE, Shahdadkot Near Grid Station, Shahdadkot 4 Larkana GIB & CE, Kandhkot Government High School, Gulsher Muhalla 5 GIB & CE, Larkana Near Main Dari Police Station, Bakrani Road, Larkana 6 GIB & CE, Lakhi Near Water Cantt, Lakhi 7 GIB & CE, Shikarpur Near Lakhi Dar, Shikarpur 1 GIB & CE, Badin Near Total Petrol Pump, Hyderabad Road, Badin 2 GIB & CE, Dadu Court Road, Dadu 3 GIB & CE, Mehar Near Degree College, Mehar 4 GIB & CE, Latifabad Behind BISE, Latifabad-9, Hyderabad -

List of Agriculture Designated Branches

LIST OF AGRICULTURE DESIGNATED BRANCHES Sr. No. Name of Branch Telephone Number 1: Sindh Province Karachi West Region 1 C.O.D 9248530/6035436 2 Kashmir Road 4553053 3 Korangi Creek 5091122 4 Korangi Fish Harbour 5016832/5015096 5 Korangi Indus.Area 5115312/5062491 6 Landhi Township` 5010351 7 M.A Jinnah Road 2294739/2294738 8 Malir City 4516099/4116109 9 Nazimabad 9260669 10 New Fruit & Veg.Market 6871034 11 North Karachi 6971672 12 Orangi Town 6651200 13 PNAD Mauripur 2814392/2039362 14 Port Qasim 9272093 15 S.I.T.E 2567788 16 Shaheed-e-Millat Road 4532771/4532587/4521142 17 Shamsi C.H Society 9248546 18 Pak Marine Academy 9241245/9241201 Hyderabad Region 1 Fatima Jinnah Road Br. 022-9200142/9200082 2 Market Area Br. 022-9210091-3 3 Muncipal Corporation Br. 022-9210170/9210172 4 C.A.Labad 022-9260135/9260037 5 New Cloth Mkt: 022-9210390 6 Tando Jam 022-2765355 7 Wapda Colony Br. 022-9260221/9260223 8 Site Area Br. 022-3880496/3884067 9 Latifabad Br. 022-9260036-38-39 Distt:Thatta 10 Chuhar Jamali Br. 0298-778021 11 Gharo Br. 0298-760013 12 Jati Br. 0298-777020/77252 13 Makli Br. 0298-920087/920088 14 Mirpur Bathoro Br. 0298-77919/779399 15 Mirpur Sakro Br. 0298-775279/775207 16 Sujawal Br. 0298-510348/510125 17 Thatta Br. 0298-923021-22 18 Var Br. 0298-774020 Distt:Mirpur Khas 19 Main Br. Mirpurkhas 0233-9290255/9290258 20 Kot Ghulam Muhammad Br. 0233-866313 21 uncipal Committee Br.Mirpurkha 0233-9290398/9290258 22 Mirwah Gorchani Br. -

PAKISTAN, YEAR 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018

PAKISTAN, YEAR 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; China/India bor- der status: CIA, 2006; Kashmir border status: CIA, 2004; geodata of disputed borders: GADM, November 2015a; Nat- ural Earth, undated; incident data: ACLED, June 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 PAKISTAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Riots/protests 3644 6 7 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 325 249 915 Development of conflict incidents in 2017 2 Remote violence 169 74 388 Violence against civilians 124 85 291 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 67 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Total 4329 414 1601 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). Localization of conflict incidents 4 Disclaimer 6 Development of conflict incidents in 2017 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). 2 PAKISTAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Methodology an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province is known.