Notes on Legal Ethics Edward A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

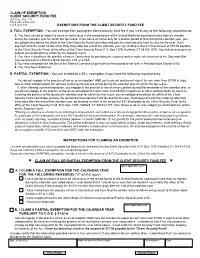

Claim of Exemption -Client Security Fund

CLAIM OF EXEMPTION CLIENT SECURITY FUND FEE JD-GC-22 Rev. 1-17 P.B. § 2-55, 2-55A, 2-70 C.G.S. § 51-81d EXEMPTIONS FROM THE CLIENT SECURITY FUND FEE A. FULL EXEMPTION - You are exempt from paying the client security fund fee if you meet any of the following requirements: 1. You have served or expect to serve on active duty in the armed forces of the United States for a period of more than six months during the calendar year for which the fee is due. If you serve on active duty for a shorter period of time during the calendar year, you are obligated to advise the office of the Client Security Fund Committee and pay the client security fund fee due for the year. Such payment shall be made no later than thirty days after the end of the calendar year, by sending a check in the amount of $75.00 payable to the Client Security Fund, to the office of the Client Security Fund, P.O. Box 1379, Hartford, CT 06143-1379. Your failure to do so may subject you to disciplinary action by the Superior Court. 2. You have retired from the practice of law in Connecticut by providing the required written notice of retirement to the Statewide Bar Counsel pursuant to Practice Book Section 2-55 or 2-55A. 3.You have resigned from the Bar of the State of Connecticut pursuant to the procedure set forth in Practice Book Section 2-52. 4. You have been disbarred. B. PARTIAL EXEMPTION - You are entitled to a 50% exemption if you meet the following requirements: You do not engage in the practice of law as an occupation* AND you have not and do not expect to earn more than $1000 in legal fees or other compensation for services involving the practice of law during the calendar year for which the fee is due. -

Expanding Employee Privacy to Protect the Attorney-Client Privilege from Employer Computer Monitoring

Protecting What You Thought Was Yours: Expanding Employee Privacy to Protect the Attorney-Client Privilege from Employer Computer Monitoring KARA R. WILLIAMS* 1. INTRODUCTION Ashlee has been working at her current job for almost two years, and she was confident that she understood her privacy rights as an employee of the company.1 However, she was completely unaware that one day, by sending a private e-mail to her private attorney from her work computer, she might have jeopardized the confidentiality of her conversations that had occurred in what she thought was strict confidence. 2 Recently, Ashlee had been experiencing some problems with her supervisor at work, and she feared that his conduct might be amounting to sexual harassment. Concerned about her safety and her job, Ashlee sought the advice of a private attorney, who instructed her to keep him informed of the conduct of her employer. One day at work, Ashlee's employer made a lewd remark to her about her body and the outfit she was wearing. Upset by this comment, Ashlee quickly went back to her office and e-mailed her private attorney from her work-provided computer, giving him a great deal of personal information, as well as information about her employer's conduct. In response, her attorney concluded that Ashlee had an actionable claim for sexual harassment, and Ashlee subsequently filed suit against her employer. Despite the private nature of the conversation, during discovery for the pending lawsuit, Ashlee's employer demanded the production of Ashlee's confidential e-mail exchange with her personal attorney. -

Maltreatment Report #: HL28659005M Compliance

Protecting, Maintaining and Improving the Health of All Minnesotans Office of Health Facility Complaints Investigative Public Report Maltreatment Report #: HL28659005M Date Concluded: May 31, 2019 Compliance #: HL28659006C Name, Address, and County of Licensee Name, Address, and County of Housing with Investigated: Services location: A‐1 Reliable Home Care A‐1 Reliable Home Care 2353 Rice Street Suite 107 5716 42nd Avenue North Saint Paul, MN 55113 Robbinsdale, MN 55422 Ramsey County Ramsey County Facility Type: Home Care Provider Investigator’s Name: Earl F. Bakke, RN, MSOL, BSN, CEN Special Investigator Revised Date: July 30, 2019 Finding: Inconclusive Nature of Visit: An investigator from the Minnesota Department of Health investigated an allegation of maltreatment, in accordance with the Minnesota Reporting of Maltreatment of Vulnerable Adults Act, Minn. Stat. 626.557, and to evaluate compliance with applicable licensing standards for the provider type. Allegation(s): It is alleged that a client was exploited when the alleged perpetrator (AP) took money from the client’s account without permission. Investigative Findings and Conclusion: Financial exploitation was inconclusive. The AP billed a client to clean a carpet damaged due to the client urinating on the floor. The AP sent the invoice to the client’s representative payee, who paid the sum in monthly installments. The AP believed s/he had justification for billing the client for the damage under the rental agreement signed by the client. There is not a preponderance of evidence to conclude that the AP intended to financially exploit the client by billing the client for the repairs to damaged property. An equal opportunity employer. -

Global 20: K&L Gates

Portfolio Media. Inc. | 860 Broadway, 6th Floor | New York, NY 10003 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Global 20: K&L Gates By Gavin Broady Law360, New York (August 06, 2013, 6:20 PM ET) -- The past year has seen K&L Gates LLP make a major push into the Asia-Pacific region by establishing new footholds in Australia and South Korea while further developing its formidable stateside practice as the firm continues to climb the ranks in its third straight appearance on Law360's Global 20. With each expansion underscored by a guiding philosophy of borderless firm integration, K&L Gates has grown a worldwide practice that now sees more than a quarter of its projected $1.2 billion revenue generated through work undertaken at multiple offices around the globe. "Through our market positioning and unique organizational structure, we try to locate the firm at what we call the critical crossroads of the 21st century: the intersection of globalization, regulation and innovation," global managing partner Peter Kalis said. "We have pursued with religious fervor a totally integrated law firm. We are indeed the largest integrated network of offices of any global law firm." Major moves made by K&L Gates in the last year include the establishment of a seventh Asian office in Seoul, the launch of two new stateside branches in the energy industry center of Houston and the business formation hub of Delaware, and the firm's expansion onto a fifth continent via its combination with Australian law firm Middletons. -

The Office Trivia Questions & Answers

Trivia Questions The Office Trivia Questions & Answers Trivia Question: The casting team originally wanted who to audition for the role of Dwight? Answer: John Krasinski Trivia Question: John Krasinski, Mindy Kaling, and who else were all, at one point, interns at Late Night With Conan O’Brien? Answer: Angela Kinsey Trivia Question: Who almost didn’t work in The Office because he was committed to another NBC show called Come to Papa? Answer: Steve Carell Trivia Question: During his embarrassing Dundie award presentation, whom is Michael Scott presenting a Dundie award when he sings along to “You Sexy Thing” by ’70s British funk band Hot Chocolate? Answer: Ryan Trivia Question: In “The Alliance” episode, Michael is asked by Oscar to donate to his nephew’s walkathon for a charity. How much money does Michael donate, not realizing that the dona- tion is per mile and not a flat amount? Answer: $25 Trivia Question: Which character became Jim’s love interest after he moved to the Stamford branch in season three and joined the Scranton office during the merger? Answer: Karen Filippelli Trivia Question: What county in Pennsylvania is Dunder Mifflin Scranton branch located? Answer: Lackawanna County Trivia Question: What is the exclusive club that Pam, Oscar, and Toby Flenderson establish in the episode “Branch Wars”? Answer: Finer Things Club Trivia Question: What substance does Jim put office supplies owned by Dwight into? Answer: Jello Trivia Question: What is the name of the employee who started out as “the temp” in the Dunder Mifflin office? Answer: Ryan Trivia Question: Rainn Wilson did not originally audition for the part of the iconic beet farm- ing Dwight Schrute, instead he auditioned for which part? Answer: Michael Scott Trivia Question: Dwight owns and runs a farm in his spare time. -

Talking to Strangers: the Use of a Cameraman in the Office and What

Running Head: TALKING TO STRANGERS 1 Talking to Strangers The Use of a Cameraman in The Office and What It Reveals about Communication Sarah Stockslager A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2010 TALKING TO STRANGERS 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Lynnda S. Beavers, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Robert Lyster, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James A. Borland, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date TALKING TO STRANGERS 3 Abstract In the television mock-documentary The Office, co-workers Jim and Pam tell the cameraman they are dating before they tell their fellow co-workers in the office. The cameraman sees them getting engaged before anyone in the office has a clue. Even the news of their pregnancy is witnessed first by the camera crew. Jim and Pam’s boss, Michael, and other employees, such as Dwight, Angela and others, also share this trend of self-disclosure to the cameraman. They reveal secrets and embarrassing stories to the cameraman, showing a private side of themselves that most of their co-workers never see. First the term “mock-documentary” is explained before specifically discussing the The Office. Next the terms and theories from scholarly sources that relate the topic of self-disclosure to strangers are reviewed. Consequential strangers, weak ties, the stranger- on-a-train phenomenon, and para-social interaction are studied in relation to the development of a new listening stranger theory. -

Client Science Instructor's Guide

THE CLIENT SCIENCE COURSE INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE By Marjorie Corman Aaron Professor of Practice Director, Center for Practice University of Cincinnati College of Law The Client Science Course | Instructor’s Guide | ©Marjorie Corman Aaron, 2013. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 1 ALTERNATIVE COURSE STRUCTURES ....................................................................................................... 2 THE FOUR‐DAY PRE‐SEMESTER CLIENT COUNSELING WORKSHOP .................................................... 3 WORKSHOP TIMING ................................................................................................................................. 3 LOGISTICS ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Workshop Days .................................................................................................................................. 4 Faculty Coverage ................................................................................................................................ 4 THE TEN‐WEEK CLIENT COUNSELING COURSE .................................................................................... 5 Timing and logistics ........................................................................................................................... 5 -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

Pension Withdrawal Liability and EFCA Arbitration

Inside 3Q2009 2...Oxymorons and Indexes 4...Pension Withdrawal Liability and EFCA Arbitration 5...Echoes of Echostar: Practical Issues Confronting Clients Accused of Patent Infringement After Seagate 8...Give Me Back My Stuff: Adding Bite to An Employer’s Demand Through the CFAA 9...Welcome New Members FOCUS President’s Message Mark Rogers There’s no doubt about it: I am taking the What that means, principally, is that we are including past easy way on this president’s letter for our providing world-class learning support in the list of items we will third quarter newsletter. I’m doing it for a and development opportunities consider in determining which very good reason, though. I want to share for our members. To that end, we firms will be selected as sponsors with the entire Arizona Chapter the letter are looking for sponsors to help us for the upcoming program year. that was sent two weeks ago to past, pres- meet that goal. For law firms, we ent and potential sponsors. Along with have three levels of sponsorship To all potential sponsors for an accompanying set of materials, it was opportunities (Platinum, Gold 2009–2010, please read through mailed to 21 law firms and eight businesses and Silver) this year (October the attached materials carefully that provide services to in-house counsel. 2009–September 2010), and, and send any questions well for the first time, we have in advance of the August 25th I am also very excited about the upcoming new categories of sponsorship deadline to accarizona@yahoo. 2009–2010 year. -

Practice Questions for Professional Responsibility Course Supplement

2018 PRACTICE QUESTIONS FOR PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY COURSE SUPPLEMENT Prof. Drury Stevenson 1 © 2018 Drury D. Stevenson Cover photo: Stone frieze of law professor lecturing while his students sleep, from the main entrance of the Yale Law School. Photo © Rena Tobey, used by permission. Note for students: These 235 questions have the same format and style as the questions on the current Multistate Professional Responsibility Exam (MPRE). The multiple-choice format also provides a useful way to test students’ knowledge of each provision or clause in each of the Model Rules, as well as the drafters’ official Comments (which the MPRE tests along with the Model Rules themselves). This particular archive of questions is a supplement to the author’s recently-published Glannon Guide to Professional Responsibility. The Glannon Guide provides detailed explanations for each of its questions (approximately 200 questions), as well as a helpful introduction to each topic. This book provides only an answer key, but has more questions. All the questions will be very useful in preparing for the exam in Professor Stevenson’s course, as well as the MPRE itself. 2 Table of Contents PART I: Material Covered on the Mid-Term Exam And Final Exam…………………….5 1. Conflicts of interest………………………………..7 2. The Client-Lawyer Relationship…………………28 3. Litigation & Other Forms of Advocacy…………46 4. Competence, Malpractice, & Other Liability…...63 PART II: Material Covered Only on the Final Exam….66 5. Client Confidentiality…………………………….67 6. Regulation of the Legal Profession……………...72 7. Communications About Legal Services……........99 8. Different Roles of the Lawyer…………………...116 9. Transactions and Communications with Persons Other Than Clients……………………..125 10. -

The Invisible Journalist: Understanding the Role of the Documentary Filmmaker As Portrayed in the Office

The Invisible Journalist: Understanding the Role of the Documentary Filmmaker as Portrayed in The Office Massiel Bobadilla JOUR575 –Joe Saltzman Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture May 5, 2011 Bobadilla 2 ABSTRACT: This study aims to shed light on the enigmatic ‘mockumentary’ filmmaker of The Office by using specific examples from the show’s first six seasons to understand how the filmmaker is impacted by and impacts concepts of journalism and the invasion of privacy. Similarly, the filmmaker in the American version of The Office will not only be compared and contrasted to the role of the filmmaker in the British version, but also will be compared to the anthropologic ethnographer an “outsider” attempting to capture life as faithfully as possible in a community to which he/she does not belong. The American interpretation of The Office branched out of Ricky Gervais’s British original of the same name with the pilot episode hitting the airwaves on NBC on March 24, 2005,1 to largely mixed reviews from critics, but a strong showing among viewers.2 The show’s basic premise is that of a faux documentary providing an inside look at the day-to-day life of the employees of a mid-level paper company. The primary focus centers on the socially inept branch manager, his even more inept right-hand-man, and the budding romance of the young and earnest paper salesman and the mild-mannered receptionist who happens to be inconveniently engaged to one of the branch’s warehouse workers. What was the Slough branch of Wernham Hogg in the U.K. -

Croatian Bar Association on 18 February, 1995

The Attorneys' Code of Ethics* * The Attorneys' Code of Ethics was passed at the Assembly of the Croatian Bar Association on 18 February, 1995. The "Amendments" were adopted at the Assembly of the CBA on 12 June, 1999. I. GENERAL PRINCIPLES 1. The Attorneys' Code of Ethics (hereinafter called: the Code) establishes the principles and rules of conduct that attorneys shall at all times follow in fulfilling their professional responsibilities and in order to preserve the dignity of, and respect for, the legal profession. 2. The basic principles are contained in the solemn oath that every attorney takes when beginning his or her professional legal activity. These principles must be a component part of each attorney's own conscience and belief. 3. The attorney's relationship towards his or her client, the adverse party and the opposing attorney, other attorneys, courts, public attorneys and other government bodies and agencies possessing public authority shall be determined by the attorney's role as the protector of the rights of citizens and legal entities. 4. In his or her appearances, submissions, speeches and other official acts and public and private appearances in general, an attorney shall always consider the requirements of professional and general culture. 5. In fulfilling his or her professional responsibilities, an attorney shall behave in such a way as to gain and maintain the trust of the client, and of the judicial and other bodies he or she appears before. 6. An attorney shall fulfill conscientiously all his or her duties that arise from the attorney's profession and preserve the reputation and the dignity of the profession both at work and in his or her private life.