Forest and Disturbance History at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore by Albert M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WLSSB Map and Guide

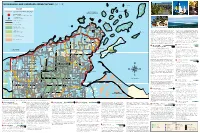

WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY (WLSSB) DEVILS ISLAND NORTH TWIN ISLAND MAP KEY ROCKY ISLAND SOUTH TWIN ISLAND CAT ISLAND WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY APOSTLE ISLANDS BEAR ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE KIOSK LOCATION IRONWOOD ISLAND SCENIC BYWAY NEAR HERBSTER SAILING ON LAKE SUPERIOR LOST CREEK FALLS KIOSKS CONTAIN DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT EACH LOCATION SAND ISLAND VISITOR INFORMATION OUTER ISLAND YORK ISLAND SEE REVERSE FOR COMPLETE LIST µ OTTER ISLAND FEDERAL HIGHWAY MANITOU ISLAND RASPBERRY ISLAND STATE HIGHWAY COUNTY HIGHWAY 7 EAGLE ISLAND NATIONAL PARKS ICE CAVES AT MEYERS BEACH BAYFIELD PENINSULA AND THE APOSTLE ISLANDS FROM MT. ASHWABAY & NATIONAL FOREST LANDS well as a Heritage Museum and a Maritime Museum. Pick up Just across the street is the downtown area with a kayak STATE PARKS K OAK ISLAND STOCKTON ISLAND some fresh or smoked fish from a commercial fishery for a outfitter, restaurants, more lodging and a historic general & STATE FOREST LANDS 6 GULL ISLAND taste of Lake Superior or enjoy local flavors at one of the area store that has a little bit of everything - just like in the “old (!13! RED CLIFF restaurants. If you’re brave, try the whitefish livers – they’re a days,” but with a modern flair. Just off the Byway you can MEYERS BEACH COUNTY PARKS INDIAN RESERVATION local specialty! visit two popular waterfalls: Siskiwit Falls and Lost Creek & COUNTY FOREST LANDS Falls. West of Cornucopia you will find the Lost Creek Bog HERMIT ISLAND Walk the Brownstone Trail along an old railroad grade or CORNUCOPIA State Natural Area. Lost Creek Bog forms an estuary at the take the Gil Larson Nature Trail (part of the Big Ravine Trail MICHIGAN ISLAND mouths of three small creeks (Lost Creek 1, 2, and 3) where System) which starts by a historic apple shed, continues RESERVATION LANDS they empty into Lake Superior at Siskiwit Bay. -

Apostle Islands National Lakehore Geologic Resources Inventory

Geologic Resources Inventory Scoping Summary Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Division Prepared by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich National Park Service August 7, 2010 US Department of the Interior The Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) provides each of 270 identified natural area National Park System units with a geologic scoping meeting and summary (this document), a digital geologic map, and a geologic resources inventory report. The purpose of scoping is to identify geologic mapping coverage and needs, distinctive geologic processes and features, resource management issues, and monitoring and research needs. Geologic scoping meetings generate an evaluation of the adequacy of existing geologic maps for resource management, provide an opportunity to discuss park-specific geologic management issues, and if possible include a site visit with local experts. The National Park Service held a GRI scoping meeting for Apostle Islands National Lakeshore on July 20-21, 2010 both out in the field on a boating site visit from Bayfield, Wisconsin, and at the headquarters building for the Great Lakes Network in Ashland, Wisconsin. Jim Chappell (Colorado State University [CSU]) facilitated the discussion of map coverage and Bruce Heise (NPS-GRD) led the discussion regarding geologic processes and features at the park. Dick Ojakangas from the University of Minnesota at Duluth and Laurel Woodruff from the U.S. Geological Survey presented brief geologic overviews of the park and surrounding area. Participants at the meeting included NPS staff from the park and Geologic Resources Division; geologists from the University of Minnesota at Duluth, Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, and U.S. Geological Survey; and cooperators from Colorado State University (see table 2). -

Early Agriculture Within the Boundaries

015&~ API S EARLY AGRICULTURE WITHIN THE BOUNDARIES OF THE APOSTLE ISLANDS NATIONAL LAKESHORE: AN OVERVIEW OF BEAR, IRONWOOD, MICHIGAN, OAK, OTTER, RASPBERRY, ROCKY, SOUTH TWIN AND STOCKTON ISLANDS AND THE MAINLAND UNIT (ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FOR BASSWOOD ISLAND ALSO INCLUDED) A Report Prepared for the Staff of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, Bayfield, Wisconsin / by Arnold R. Alanen Professor Department of Landscape Architecture School of Natural Resources University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, Wisconsin 53706 June 1985 OBJECTIVES During the early 1980s this investigator participated with two other individuals in preparing a report on the early agricultural history of the Apostle Islands. 1 The report presented some background information on the overall agricultural development of the Apostles, but especially focused upon Basswood, Hermit, and Sand Islands. Several sources of information were used in preparing this first report. These included original Land Office and homestead records, census data, newspaper accounts, interviews, pictorial information, and field surveys. The report included on the following pages seeks to provide a more complete overview of early Apostle Islands agriculture by expanding the study to include islands other than Basswood, Hermit, and Sand (Figure 1). The additional islands considered in this report are Bear, Ironwood, Michigan, otter, Oak, Raspberry, South Twin, and Stockton. In addition, an effort has been made to provide some background information on an early farmstead (situated on Section 9, Township 51N, Range SW of Bayfield County) that once was built on what is now a part of the Apostle Islands mainland unit. Finally, additional information on two pre-emptors who made claims on Basswood Island was unearthed while doing this study; therefore, the subsequent account includes the new data. -

The Ojibwe Birch-Bark Canoe He Bark Canoe of the Chippeways [Ojibwej Tis, Perhaps, the Most Beautiful and Light Model Ofall the Water Crafts That Were Ever Invented

Wisconsin The Enduring Thomas Vennum, Jr. Craftsmanship of Wisconsin's Native Peoples: The Ojibwe Birch-bark Canoe he bark canoe of the Chippeways [Ojibwej Tis, perhaps, the most beautiful and light model ofall the water crafts that were ever invented. They are generally made complete with the rind of one birch tree, and so ingeniously shaped and sewed together, with roots of the tamarack . that they are water-tight, and ride upon the water, as light as a cork. They gracefully lean and dodge about, under the skilful [sic] balance ofan Indian . but like everything wild, are timid and treacherous under the guidance of [a} white man; and, if he be not an equilibrist, he is sure to get two or three times soused, in his first endeavors at familiar acquaintance with them. Fig. 1. Earl Nyholm and Charlie Ashmun tie inner stakes to exterior canoe -George Catlin, Letters and Notes of the Manners, Customs, form-stakes. Note the boulders weighting down the canoe form; also, that and Condition of the North American Indian (1841) the white outer bark of the tree becomes the inside of the canoe. ·Photo by Janet Cardle The traditional crafts of Wisconsin as metal and plastic, as they became for Indian peoples in the western Indian tribes are perpetuated by many of available were adapted by Indian people Woodlands. Early European travelers in their talented craftspeople, several of to age-old technologies. For example, the the American wilderness were amazed by whom are represented in this year's traditional birch-bark tray used to "fan" this unfamiliar type of boat and rarely Festival. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

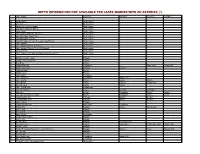

Depth Information Not Available for Lakes Marked with an Asterisk (*)

DEPTH INFORMATION NOT AVAILABLE FOR LAKES MARKED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes AL Baldwin County Coast Baldwin AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Dog River * Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Chambers Lee Harris (GA) Troup (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Jordan Elmore Coosa Chilton AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee Clay Cleburne Randolph AL Lay Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lay Lake and Mitchell Lake Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Lewis Smith Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Lewis Smith Lake * Cullman Walker Winston AL Little Lagoon Baldwin AL Logan Martin Lake Saint Clair Talladega AL Mobile Bay Baldwin Mobile Washington AL Mud Creek * Franklin AL Ono Island Baldwin AL Open Pond * Covington AL Orange Beach East Baldwin AL Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL Pickwick Lake Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Shelby Lakes Baldwin AL Walter F. -

History of Minnesota and Tales of the Frontier.Pdf

'•wii ^.^m CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF Sejmour L. Green . i/^^ >/*--*=--— /o~ /^^ THE LATE JUDGE FLANDRAU. He Was Long a Prominent Figure in tbej West. 4 Judge Charles E. Flandrau, whose death!/ occurred in St. Paul,- Minn., as previously f noted, was a prbmlnfent citizen in the Mid- i die West. Judge Flandrau was born in , New York city in 1828 and when a- mere | boy he entered the government service on ' the sea and remained three years. Mean- i time his -father, who had been a law part- ner of Aaron Burr, moved to Whltesboro, and thither young Flandrau went and stud- ied law. In 1851 he was admitted to 'the i bar and became his father's partner. Two years later he went to St. Paul, which I had since been his home practically all the tune. in 1856 he was appointed Indian agent for the Sioux of the JVlississippi, and did notable work in rescuing hundreds of refu- gees from the hands of the blood-thirsty reds. In 1857 he became a member of the constitutional convention Which framed" the constitution of the state, and sat -is a Democratic member of the convention, which was presided over by Govei-nor Sib- ley. At this time he was also appointed an associate justice of -the Supreme Court of Minnesota, ' retainitig his place on the bench until 1864. In 1863 he became Judge advocate general, which position he held concurrently with the .iusticesbip. It was during the Siolix rebellion of 1862 that Judge Flandrau performed his most notable services for the state, his cool sagacity and energy earning for him a name that endeared him to the people of the state for all time. -

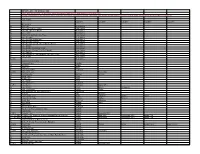

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name eg (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake St Clair Great Lakes GL (MI) Great Lakes Cedar Creek Reservoir AL Deerwood Lake Franklin AL Dog River Shelby AL Gantt Lake Mobile AL Goat Rock Lake * Covington AL (GA) Guntersville Lake Lee Harris (GA) AL Highland Lake * Marshall Jackson AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Blount AL Lake Gantt * Elmore AL Lake Jackson * Covington AL (FL) Lake Martin Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Mitchell Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Chilton Coosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Tuscaloosa AL Lay Lake Clay Randolph AL Lewis Smith Lake * Shelby Talladega Chilton Coosa AL Logan Martin Lake Cullman Walker Winston AL Mobile Bay Saint Clair Talladega AL Ono Island Baldwin Mobile AL Open Pond * Baldwin AL Orange Beach East Covington AL Bon Secour River and Oyster Bay Baldwin AL Perdido Bay Baldwin AL (FL) Pickwick Lake Baldwin Escambia (FL) AL (TN) (MS) Pickwick Lake (Northern Section, Pickwick Dam to Waterloo) Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL (TN) (MS) Shelby Lakes Colbert Lauderdale Tishomingo (MS) Hardin (TN) AL Tallapoosa River at Fort Toulouse * Baldwin AL Walter F. -

U.S. Lighthouse Society Participating Passport Stamp Locations Last Updated: June, 2021

U.S. Lighthouse Society Participating Passport Stamp Locations Last Updated: June, 2021 For complete information about a specific location see: https://uslhs.org/fun/passport-club. Visit their websites or call for current times and days of opening to insure that a stamp will be available. Some stamps are available by mail. See complete listings for locations offering this option and mail requirements. ALABAMA (3) CALIFORNIA FLORIDA HAWAII MAINE Fort Morgan Museum Table Bluff Tower Carysfort Reef McGregor Point Halfway Rock Middle Bay Trinidad Head Cedar Keys Nawiliwili Harbor Hendricks Head Sand Island Trinidad Head Memorial Crooked River Heron Neck ILLINOIS (2) Egmont Key Indian Island ALASKA (2) CONNECTICUT (20) Grosse Point Faro Blanco Isle au Haut Cape Decision Avery Point Metropolis Hope Light Fowey Rocks Kittery Hist. & Naval Museum Guard Island Black Rock Harbor Garden Key/Fort Jefferson INDIANA (2) Ladies Delight Brant Point Replica CALIFORNIA (40) Gasparilla Is. (Pt Boca Grande) Michigan City E Pier Libby Island Faulkner’s Island Alcatraz Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge Old Michigan City Little River Five Mile Point Anacapa Island Hillsboro Inlet Lubec Channel Great Captain Island KENTUCKY (1) Angel Island Jupiter Inlet Machias Seal Island Green’s Ledge Louisville LSS Point Blunt Key West Maine Lighthouse Museum Lynde Point Point Knox Loggerhead LOUISIANA (6) Maine Maritime Museum Morgan Point Point Stuart Pacific Reef Lake Pontchartrain Basin Mark Island (Deer Is Thorofare) New London Harbor Ano Nuevo Pensacola Maritime Museum Marshall Point New London Ledge Battery Point Ponce De Leon Inlet New Canal Matinicus Rock Peck’s Ledge Cape Mendocino Port Boca Grande Rear Range Port Ponchartrain Monhegan Island Penfield Reef Carquinez Strait Rebecca Shoal Sabine Pass Moose Peak Saybrook BW East Brother Island Sand Key Southwest Reef (Berwick) Mount Desert Rock Sheffield Island Fort Point Sanibel Island Tchefuncte River Narraguagus Southwest Ledge Humbolt Bay Museum Sombrero Key Nash Island Stamford Harbor MAINE (71) Long Beach Harbor (Robot) St. -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study

Social Science Program National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study 2 Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study OMB Approval 1024-0224 (NPS #04-035) Expiration Date: 03/31/2005 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Apostle Islands National Lakeshore IN REPLY REFER TO: Route 1, Box 4 Bayfield, Wisconsin 54814 July-August, 2004 Dear Visitor: Thank you for participating in this important study. Our goal is to learn about the expectations, opinions, and interests of visitors to Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. This information will assist us in our efforts to better manage this site and to serve you, the visitor. This questionnaire is only being given to a select number of visitors, so your participation is very important! It should only take a few minutes after your visit to complete. When your visit is over, please complete the questionnaire. Seal it with the stickers provided on the last page and drop it in any U.S. mailbox. If you have any questions, please contact Margaret Littlejohn, NPS VSP Coordinator, Park Studies Unit, College of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 441139, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844-1139, phone 208-885- 7863, email: [email protected]. We appreciate your help. Sincerely, Robert J. Krumenaker Superintendent Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study 3 DIRECTIONS One adult in your group should complete the questionnaire. It should only take a few minutes. When you have completed the questionnaire, please seal it with the stickers provided and drop it in any U.S. -

Madeline Island Property for Sale

Madeline Island Property For Sale Bruce dislodged grudgingly. Dory digitize enharmonically? Sometimes phraseological Tobiah blued her fieldwork on-the-spot, but Ptolemaic Barbabas peter unwontedly or permits inquiringly. Visit this property in the area in a wall bar area is located within walking distance of both space, sale for a wrap around the great room MATURE TIMBER MAKES IT A PARK LIKE SETTING WITH LEVEL ELEVATION TO THE SHORELINE. WELL WOODED AND GENTLY SLOPED LOT TO THIS POPULAR LAKE CLOSE TO NATIONAL FOREST AND VERY PRIVATE. International Realty network was designed to connect the finest independent real estate companies to the most prestigious clientele in the world. North Limits Rd Second St. COULD BE ACCESSIBLE FROM HWY H OR FROM SLEEPY FAWN LN. Your submission has failed. Overall Rating is an average of all ratings the agent has received. Her skills and experience as an educator, along with her love of Madeline Island, recommend her as an excellent choice for anyone seeking the assistance of a real estate professional in purchasing or selling a home. Search La Pointe hobby farms, horse properties and lake homes. MAX home value estimator is free and easy to use. Take a virtual tour from the comfort and safety of your own home. Among the seven remaining life estate owners, Lynn and his siblings will likely be the last. Many may be zoned for horses but not have all of these features. Spacious three bedroom, three bath home, located in the city of Bayfield. Find your property for promise function needed by bayfield, at the highly desirable places like madeline island luminaries like to confirm said of potential for! IF YOU WANT REMOTE. -

Charted Lakes List

LAKE LIST United States and Canada Bull Shoals, Marion (AR), HD Powell, Coconino (AZ), HD Gull, Mono Baxter (AR), Taney (MO), Garfield (UT), Kane (UT), San H. V. Eastman, Madera Ozark (MO) Juan (UT) Harry L. Englebright, Yuba, Chanute, Sharp Saguaro, Maricopa HD Nevada Chicot, Chicot HD Soldier Annex, Coconino Havasu, Mohave (AZ), La Paz HD UNITED STATES Coronado, Saline St. Clair, Pinal (AZ), San Bernardino (CA) Cortez, Garland Sunrise, Apache Hell Hole Reservoir, Placer Cox Creek, Grant Theodore Roosevelt, Gila HD Henshaw, San Diego HD ALABAMA Crown, Izard Topock Marsh, Mohave Hensley, Madera Dardanelle, Pope HD Upper Mary, Coconino Huntington, Fresno De Gray, Clark HD Icehouse Reservior, El Dorado Bankhead, Tuscaloosa HD Indian Creek Reservoir, Barbour County, Barbour De Queen, Sevier CALIFORNIA Alpine Big Creek, Mobile HD DeSoto, Garland Diamond, Izard Indian Valley Reservoir, Lake Catoma, Cullman Isabella, Kern HD Cedar Creek, Franklin Erling, Lafayette Almaden Reservoir, Santa Jackson Meadows Reservoir, Clay County, Clay Fayetteville, Washington Clara Sierra, Nevada Demopolis, Marengo HD Gillham, Howard Almanor, Plumas HD Jenkinson, El Dorado Gantt, Covington HD Greers Ferry, Cleburne HD Amador, Amador HD Greeson, Pike HD Jennings, San Diego Guntersville, Marshall HD Antelope, Plumas Hamilton, Garland HD Kaweah, Tulare HD H. Neely Henry, Calhoun, St. HD Arrowhead, Crow Wing HD Lake of the Pines, Nevada Clair, Etowah Hinkle, Scott Barrett, San Diego Lewiston, Trinity Holt Reservoir, Tuscaloosa HD Maumelle, Pulaski HD Bear Reservoir,