Revised Away for the Day.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M a R T I N Woolley Landscape Architects

OLDHAM MILLS STRATEGY LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW February 2020 MARTIN WOOLLEY LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DOCUMENT CONTROL TITLE: LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW PROJECT: OLDHAM MILLS STRATEGY JOB NO: L2.470 CLIENT: ELG PLANNING for OLDHAM MBC Copyright of Martin Woolley Landscape Architects. All Rights Reserved Status Date Notes Revision Approved DRAFT 2.3.20 Draft issue 1 MW DRAFT 24.3.20 Draft issue 2 MW DRAFT 17.4.20 Draft issue 3 MW DRAFT 28.7.20 Draft issue 4 MW CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Scope 3 Methodology 3 BACKGROUND Background History 6 Historical Map 1907 7 LANDSCAPE BASELINE Topography & Watercourses 11 Bedrock Geology 12 National Character Areas 13 Local Landscape Character 14 GMC Landscape Sensitivity 15 Conservation Areas 16 Greenbelt 17 Listed, Converted, or Demolished Mills (or consented) 18 ASSESSMENT Assessment of Landscape Value 20 Remaining Mills Assessed for Landscape Value 21 Viewpoint Location Plan 22 Viewpoints 1 to 21 23 High Landscape Value Mills 44 Medium Landscape Value Mills 45 Low Landscape Value Mills 46 CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS Conclusions 48 Recommendations 48 Recommended Mill Clusters 50 APPENDIX Landscape Assessment Matrix 52 1 SCOPE 1.0 SCOPE 1.1 Martin Woolley Landscape Architects were appointed in November 2019 to undertake 2.4 A photographic record of the key views of each mill assisted the assessment stage and a Landscape Overview to accompany a Mill Strategy commissioned by Oldham provided panoramic base photographs for enabling visualisation of the landscape if a Metropolitan Borough Council. particular mill were to be removed. 1.2 The Landscape Overview is provided as a separate report providing an overall analysis 2.5 To further assist the assessment process, a range of ‘reverse montage’ photographs were of the contribution existing mills make to the landscape character of Oldham District. -

The Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns

‘Views Grim But Splendid’ - Te Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns A Roberts PhD 2016 ‘Views Grim But Splendid’ - Te Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns Amber Roberts o 2016 Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 21 01 Literature Review 53 02 Research Methods 81 Region’ 119 155 181 215 245 275 298 1 Acknowledgements 2 3 Abstract ‘What is the urban image of the north- western post-industrial town?’ 4 00 Introduction This research focuses on the urban image of North West English historic cultural images, the built environment and the growing the towns in art, urban planning and the built environment throughout case of Stockport. Tesis Introduction 5 urban development that has become a central concern in the towns. 6 the plans also engage with the past through their strategies towards interest in urban image has led to a visual approach that interrogates This allows a more nuanced understanding of the wider disseminated image of the towns. This focuses on the represented image of the and the wider rural areas of the Lancashire Plain and the Pennines. Tesis Introduction 7 restructuring the town in successive phases and reimagining its future 8 development of urban image now that the towns have lost their Tesis Introduction 9 Figure 0.1, showing the M60 passing the start of the River Mersey at Stockport, image author’s own, May 2013. 10 of towns in the North West. These towns have been in a state of utopianism. persistent cultural images of the North which the towns seek to is also something which is missing from the growing literature on Tesis Introduction 11 to compare the homogenous cultural image to the built environment models to follow. -

Dukinfield) OLD CHAPEL and the UN1 TA R I a N STORY

OLD CHAPEL AND THE UNITARIAN- - STORY (Dukinfield) OLD CHAPEL AND THE UN1 TA R I A N STORY DAVID C. DOEL UNITARIAN PUBLICATION Lindsey Press 1 Essex Street Strand London WC2R 3HY ISBN 0 853 19 049 6 Printed by Jervis Printers 78 Stockport Road Ashton-Under-Lyne Tameside CONTENTS PREFACE CHAPTER ONE: AN OLD CHAPEL HERITAGE TRAIL CHAPTER TWO: BIDDLE AND THE SOCINIANS CHAPTER THREE: THE CIVIL WAR CHAPTER FOUR: MILTON AND LOCKE CHAPTER FIVE: SAMUEL ANGIER AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES CHAPTER SIX: JOSEPH PRIESTLEY CHAPTER SEVEN: WILLIAM ELLERY CHANNING CHAPTER EIGHT: FIRST HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY CHAPTER NINE: HOPPS, MARTINEAU AND WICKSTEED CHAPTER TEN: FIRST HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY CHAPTER ELEVEN: SECOND HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY APPENDIX Ai WHERE THE STORY BEGINS APPENDIX B: THE TRINITY APPENDIX C: THE ALLEGORICAL METHOD APPENDIX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDIX E: GLOSSARY SIX ILLUSTRATIONS: a) Old Chapel exterior b) Old Chapel interior c) The original Chapel d) The Old School e) The New School f) The Original Schoc! OLD CHAPEL, DUKlNFlELD PREFACE Old Testament prophets, or was he a unique expression, once and once only, of God on earth in human form? OLD CHAPEL AND THE UNITARIAN STORY is an account of the life and history of Old Chapel, Dukinfield, set within the As I point out in the Appendix on The Trinity, there emerged larger context of the story of the growth and devlopment of from all this conflict not one doctrine of the Trinity, but many. Unitarianism, which we, the present congregation, inherit from the trials and tribulations, the courage, vision and the joy The Trinity is a theological model for expressing the Nature of of our ancestors. -

Yorkshire Rail Campaigner Number 48 – March 2020

Yorkshire Rail Campaigner Number 48 – March 2020 Yorkshire President: Alan Whitehouse: Vice-Presidents: Mike Crowhurst, Alan Williams & Chris Hyomes Trans-Pennine Upgrade Under Threat! By Mark Parry With the proposed trans-Pennine high speed line being supported, we feared the upgrade of the existing line had been quietly forgotten. Transpennine Express new rolling stock at Manchester Piccadilly–Photo by Robert Pritchard The following is a joint press release from our branch and HADRAG: The Halifax & District Rail Action Group; SHRUG: Stalybridge to Huddersfield Rail Users Group; UCVRSTG: Upper Calder Valley Renaissance Sustainable Transport Group. CAMPAIGNERS in West Yorkshire are extremely concerned about lack of progress by the Government and Network Rail on infrastructure proposals that should deliver improvements for travellers in the next few years, including the TransPennine Route Upgrade (TRU). Three rail user groups and the Yorkshire Branch of Railfuture have written to Andrew Haines, Chief Executive of Network Rail, who was recently been quoted as casting doubt on TRU. In a magazine interview (RAIL 897, 29 Jan’2020) Haines had said the scope of TRU could depend on the high-speed rail proposal “Northern Powerhouse Rail” (NPR). The campaigners say NPR is decades away and will not benefit stations on regional routes that desperately need investment now. Continued overleaf… Railfuture, Yorkshire & North West Joint Branch Meeting This meeting has been postponed because of concerns about the Coronavirus. We will contact members later about alterative arrangements. 1 | Railfuture: Yorkshire Rail Campaigner 4 8 – M a r c h 2020 The campaigners have also written to Secretary of State for Transport Grant Shapps MP, and to the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak, calling for urgent, overdue projects to go ahead without further delay. -

Margaret Joyce Fountain Acey

Addendum #2 2003 April 12, 2004 To celebrate what would have been her 66th birthday in 2003, the author decided to create a timeline covering 1937 to 1957. Anyone reading this can feel free to add in some dates or tidbits of information! Margaret Joyce Fountain 1937-1958, BIRTH TO MARRIAGE Birth Beech Mount Maternity Home in Harpurhey October 15, 1937 (North Manchester Maternity Home) (see Appendix A for more on this facility) Address 15 Chesney Avenue, Chadderton (see center of map below) notes per her mother, Elsie Taylor Fountain Paine, 1992 … And now the church going. When she was young, some neighbors took a few of the children to a small Methodist Church in Turf Lane, Chadderton. Later she went to the Anglican Church in New Moston, much nearer home. After we moved to the shop at Grotton, she went to Lees Methodist Church. Church Methodist, Turf Lane, Chadderton (see map on previous page, NE corner) Turf Lane, Methodist Church, Chadderton1 “With reference to your e-mail enquiry of 7 July concerning Turf Lane Methodist Church, Chadderton. The church was completed in November 1889. Turf Lane closed in 1967 when it amalgamated with Washbrook, Eaves Lane, Edward Street, Werneth and Cowhill Methodist Churches. A new South Chadderton Methodist Church was built in 1969. Chadderton Council bought the old church building in September 1969. 1 E-mail received 7/10/03, Jennifer Clark - Local Studies Assistant, Oldham Local Studies & Archives, 84 Union Street, OLDHAM, OL1 1DN, [email protected] The building was demolished and the site later re-developed.” NOTE: according to Manchester Archives site, this was apparently a Wesleyan Methodist Church. -

Notes. [299 .1 the Heywoods of Heywood

127 _ Jfriba , Auguzt 9th, 1907 . NOTES. [299 .1 THE HEYWOODS OF HEYWOOD . THE FAMILY IN THE ISLE OF MAN . SOME FURTHER NOTES . To supplement and correct the article from the "Manx Note Book," printed at No . 297, let me offer the following brief notes :- First as to the date of the Heywood char- ter, I would refer the reader to the note een- tribu,ted to this column by Dr. Hunt, a few months--ago . The assertion that "Peter Hey- wood, who died in 1657, was sixteenth in descent from Piers, living 1164," is not, I think, strictly correct, the pedigree from which that statement is taken being not quite ecmplete . Most of the sons and daughters of Gover- nor Heywood were buried, married, and bap- tised in Kirk Malew, and their names entered in the parish registers . During a recent stay at the Isle of Man, I viuited this old church . My visit was really a pilgrimage . Not an affectionate pilgrimage, not a religious pil- grimage, merely a pilgrimage of idle curiosity! I had seen this place mentioned so often in the Heywood pedigree that I thought I would like to see it. After looking up the locality on the map, I started off one fine morning in early June-fine, for the bad weather of that awful month had not yet commenced . Leav- ing Peel, changing trains at Douglas, and dis- mounting at - Ballasalla was the first part of my journey . Near Ballasalla stands Rushen Abbey, now only a few bare ruins, a tower, a Crypt, and a remnant of the -walls . -

The Bugle ------Royton Local History Society's Newsletter

No 38 March 2015 ------------------------------------------------------ The Bugle ------------------------------------------------------ Royton Local History Society's Newsletter Although we have not met between December 2014 and March 2015 the Society has continued operating in the background. I had a long and fruitful conversation with Cllr. Stephen Bashforth where he outlined future plans for our town and how he would like our input before work begins. Construction of the new leisure centre is now well under way and is due to open in September 2015. The old baths will then be demolished to make way for a car park for the new centre. We have already made representation to our councillors to try to preserve the carved stonework above the entrance to the old baths and somehow display/incorporate it into the new building. Cllr. Bashforth is fully supportive and would like to hear suggestions on how this should be done. If you have any thoughts on this matter please let me know and I will log all suggestions and present them to Cllr. Bashforth at a meeting to be arranged sometime soon. If you would like to be present at the meeting and put forward your suggestion personally I can arrange that too. Secondly, due to changes to be made to the Youth services in the Oldham Borough, a large room on the top floor of the Town Hall will soon become available and could become a Royton Museum. Once again Cllr. Bashforth is asking for our help in planning, and although there are already some exhibits in storage he would like donations of artefacts, either on loan or as gifts to the town, that can be put on display. -

Owls 2020 11

'e-Owls' Contact us : Branch Website: https://www.mlfhs.uk/oldham MLFHS homepage : https://www.mlfhs.uk/ Email Chairman : [email protected] Emails General : [email protected] Email Newsletter Ed : [email protected] MLFHS mailing address is: Manchester & Lancashire Family History Society, 3rd Floor, Manchester Central Library, St. Peter's Square, Manchester, M2 5PD, United Kingdom November 2020 MLFHS - Oldham Branch Newsletter Where to find things in the newsletter: Oldham Branch News : ............... Page 3 From the e-Postbag : ....................Page 10 Other Branch Meetings : ............. Page 3 Peterloo Bi-Centenary : .................Page 20 MLFHS Updates : ....................... Page 3 Need Help! : ...................................Page 21 Societies not part of MLFHS : ..... Page 4 Useful Website Links : ....................Page 22 'A Mixed Bag' : .............................Page 4 For the Gallery : ..............................Page 23 Branch News : Following March's Annual Meeting of the MLFHS Oldham Branch Branch Officers for 2020 -2021 : Committee Member : Chairman : Linda Richardson Committee Member : Treasurer : Gill Melton Committee Member : Secretary : Position vacant Committee Member : Newsletter : Sheila Goodyear Committee Member : Webmistress : Sheila Goodyear '1820s Market Street, Manchester' Committee Member : Dorothy Clegg from, Committee Member : Joan Harrison 'Old Manchester - a Series of Views' Intro. by James Croston, pub. 18975 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Oldham Branch Meetings : Coronavirus Pandemic Please note ... with great regret but in-line with the updated Statement, issued by the M&LFHS Trustees, and on the home page of the Society website, all M&LFHS Meetings, Branch Meetings and other public activities are to be suspended indefinitely. Please check with the website for updated information. The newsletter will be sent out as usual. There will be further updates on the Society website Home Page and on the Branch pages. -

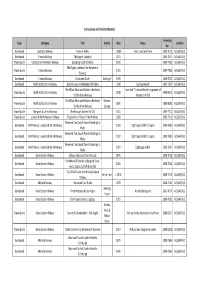

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

South Yorkshire

INDUSTRIAL HISTORY of SOUTH RKSHI E Association for Industrial Archaeology CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 STEEL 26 10 TEXTILE 2 FARMING, FOOD AND The cementation process 26 Wool 53 DRINK, WOODLANDS Crucible steel 27 Cotton 54 Land drainage 4 Wire 29 Linen weaving 54 Farm Engine houses 4 The 19thC steel revolution 31 Artificial fibres 55 Corn milling 5 Alloy steels 32 Clothing 55 Water Corn Mills 5 Forging and rolling 33 11 OTHER MANUFACTUR- Windmills 6 Magnets 34 ING INDUSTRIES Steam corn mills 6 Don Valley & Sheffield maps 35 Chemicals 56 Other foods 6 South Yorkshire map 36-7 Upholstery 57 Maltings 7 7 ENGINEERING AND Tanning 57 Breweries 7 VEHICLES 38 Paper 57 Snuff 8 Engineering 38 Printing 58 Woodlands and timber 8 Ships and boats 40 12 GAS, ELECTRICITY, 3 COAL 9 Railway vehicles 40 SEWERAGE Coal settlements 14 Road vehicles 41 Gas 59 4 OTHER MINERALS AND 8 CUTLERY AND Electricity 59 MINERAL PRODUCTS 15 SILVERWARE 42 Water 60 Lime 15 Cutlery 42 Sewerage 61 Ruddle 16 Hand forges 42 13 TRANSPORT Bricks 16 Water power 43 Roads 62 Fireclay 16 Workshops 44 Canals 64 Pottery 17 Silverware 45 Tramroads 65 Glass 17 Other products 48 Railways 66 5 IRON 19 Handles and scales 48 Town Trams 68 Iron mining 19 9 EDGE TOOLS Other road transport 68 Foundries 22 Agricultural tools 49 14 MUSEUMS 69 Wrought iron and water power 23 Other Edge Tools and Files 50 Index 70 Further reading 71 USING THIS BOOK South Yorkshire has a long history of industry including water power, iron, steel, engineering, coal, textiles, and glass. -

Dear Old Dirty Stalybridge’, C.1830-1875

Leisure and Masculinity in ‘Dear Old Dirty Stalybridge’, c.1830-1875. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Nathan Booth School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Table of Contents List of Illustrations .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Copyright Statement ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 10 The Provinces in Urban History ...................................................................................................................... -

Greater Manchester Transport Campaign

Greater Manchester Transport Campaign OCTOBER 2008 Website: http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/gmtransportcampaign/ No.9 After four years of repeated requests for a shelter here outside Urbis, we’ve finally received a firm promise one will soon be provided — but we won’t be celebrating until we see it in position (page 8). INVITATION Dear Members and Friends, Our next Open Public Meeting is to be held on Tuesday 28th October at 7 pm at the Friends’ Meeting House, Mount Street, Manchester (behind the Central Library, St Peter’s Square) to which you are invited. Light refreshments will be available from 6.30 pm and our speaker will be Mr Philip Purdy, the new Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive Director for Metrolink. Mr Purdy was previously the Asset Development Manager at Yarra Trams which operates 150 miles of tramway in Melbourne, Australia. The Independent Voice for Public Transport Users in Greater Manchester This is an opportunity to learn about the future plans and hopes for our Metrolink and of course there will be time for your questions. Do come and bring a friend. RAIL UPDATE BY ANDREW MACFARLANE We now have a closure date for the Manchester Victoria – Oldham – Rochdale “Oldham Loop” line. The last trains will run on Saturday 3rd October 2009. As mentioned in the last issue, the highly regrettable decision was made to go for closure of the line in one fell swoop rather than a staged closure. It would have been possible to convert the line as far as Shaw with a new Metrolink station to the south of the level crossing whilst maintaining a rail service from the existing Shaw & Crompton station via Rochdale to Manchester.