Licensing and Subsidising Pharmaceuticals in Australia - Reforms Needed to Deliver Transparency, Safety and Value for Money

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orphenadrine Hydrochloride 50Mg/5Ml Oral Solution Rare (Affect More Than 1 in 10,000 People) N Forgetting Things More Than Usual

Uncommon (affect more than 1 in 1000 people) n Constipation Package Leaflet: Information for the user n Greater sensitivity to things around you or feeling nervous n Feeling light-headed and an unusual feeling of excitement (elation) n Difficulty sleeping or feeling tired. Orphenadrine Hydrochloride 50mg/5ml Oral Solution Rare (affect more than 1 in 10,000 people) n Forgetting things more than usual. Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. Reporting of side effects n Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor, n If you have any further questions, ask your doctor pharmacist or nurse. This includes any possible side or pharmacist. effects not listed in this leaflet. You can also report n This medicine has been prescribed for you only. side effects directly (see details below). By reporting Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even side effects you can help provide more information on if their signs of illness are the same as yours. the safety of this medicine. n If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or United Kingdom pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this Yellow Card Scheme leaflet. See section 4. Website: www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or What is in this leaflet: Apple App Store. 1. What Orphenadrine Hydrochloride Oral Solution is and what is it used for 2. -

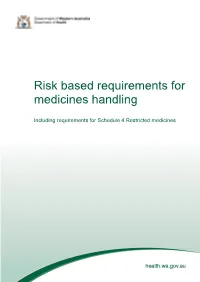

Risk Based Requirements for Medicines Handling

Risk based requirements for medicines handling Including requirements for Schedule 4 Restricted medicines Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of roles and responsibilities 3 3. Schedule 4 Restricted medicines 4 4. Medicines acquisition 4 5. Storage of medicines, including control of access to storage 4 5.1. Staff access to medicines storage areas 5 5.2. Storage of S4R medicines 5 5.3. Storage of S4R medicines for medical emergencies 6 5.4. Access to storage for S4R and S8 medicines 6 5.5. Pharmacy Department access, including after hours 7 5.6. After-hours access to S8 medicines in the Pharmacy Department 7 5.7. Storage of nitrous oxide 8 5.8. Management of patients’ own medicines 8 6. Distribution of medicines 9 6.1. Distribution outside Pharmacy Department operating hours 10 6.2. Distribution of S4R and S8 medicines 10 7. Administration of medicines to patients 11 7.1. Self-administration of scheduled medicines by patients 11 7.2. Administration of S8 medicines 11 8. Supply of medicines to patients 12 8.1. Supply of scheduled medicines to patients by health professionals other than pharmacists 12 9. Record keeping 13 9.1. General record keeping requirements for S4R medicines 13 9.2. Management of the distribution and archiving of S8 registers 14 9.3. Inventories of S4R medicines 14 9.4. Inventories of S8 medicines 15 10. Destruction and discards of S4R and S8 medicines 15 11. Management of oral liquid S4R and S8 medicines 16 12. Cannabis based products 17 13. Management of opioid pharmacotherapy 18 14. -

Atomoxetine: a New Pharmacotherapeutic Approach in the Management of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

i26 Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.2004.059386 on 21 January 2005. Downloaded from Atomoxetine: a new pharmacotherapeutic approach in the management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder J Barton ............................................................................................................................... Arch Dis Child 2005;90(Suppl I):i26–i29. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059386 Atomoxetine is a novel, non-stimulant, highly selective lifespan including a potential requirement for lifelong treatment.4 Because of the limitations of noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor that has been studied for existing treatments and the paradigm shift in use in the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity thinking about the management of ADHD, there disorder (ADHD). Data from clinical trials show it to be well is an interest in the development of new pharmacological treatments. tolerated and effective in the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults. Improvements were seen ATOMOXETINE HYDROCHLORIDE: A not only in core symptoms of ADHD, but also in broader NOVEL TREATMENT FOR ADHD social and family functioning and self esteem. Once-daily Atomoxetine is the first non-stimulant to be approved for the treatment of ADHD and the first dosing of atomoxetine has been shown to be effective in drug to be licensed for the treatment of ADHD in providing continuous symptom relief. Atomoxetine does adults.5 Atomoxetine was licensed in the US in not appear to have abuse potential and is associated with November 2002 and in the UK in May 2004. At the time of writing, it is under consideration for a benign side effect profile. The development of licensing by the regulatory authorities in a atomoxetine thus represents an important advance in the number of other countries. -

Prescription Regulations Summary Chart Who Hold an Approval to Prescribe Methadone from Their

Products included in the Triplicate Prescription Program* This is a reference list provided for convenience. While all generic medication names appear, only sample brand names are provided and it should not be viewed as an all-inclusive listing of all trade names of drugs included in the Triplicate Prescription Program. BUPRENORPHINE METHADONE BuTrans, Suboxone** Metadol, Methadose - May only be prescribed by physicians Prescription regulations summary chart who hold an approval to prescribe methadone from their BUTALBITAL PREPARATIONS provincial regulatory body*** Summary of federal and provincial laws governing prescription drug ordering, Fiorinal, Fiorinal C ¼ & C ½, Pronal, Ratio-Tecnal, records, prescription requirements, and refills Ratio-Tecnal C ¼ & C ½, Trianal, Trianal C ½ METHYLPHENIDATE Biphentin®, Foquest®, and Concerta® brands are excluded Revised 2019 BUTORPHANOL from TPP prescr ip t i o n p a d req u ir e m e n t s (generic versions Butorphanol NS, PMS-Butorphanol, Torbutrol (Vet), of these products require a triplicate presc ription) Torbugesic (Vet) Apo-Methyphenidate, PHL-Methylphenidate, PMS- Prescription regulations DEXTROPROPOXYPHENE Methylphenidate, PMS-Methylphenidate ER, Ratio- None identified Methylphenidate, Ritalin, Ritalin SR, Sandoz- According to the Standards of Practice for Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians: Methylphenidate SR, Teva-Methylphenidate ER-C FENTANYL/SUFENTANIL/ALFENTANIL 6.4 Neither a pharmacist nor a pharmacy technician may dispense a drug or blood product under a Alfentanil Injection, -

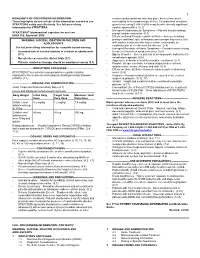

STRATTERA Safely and Effectively

1 HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION serious cardiac problems that may place them at increased These highlights do not include all the information needed to use vulnerability to its noradrenergic effects. Consideration should be STRATTERA safely and effectively. See full prescribing given to not using STRATTERA in adults with clinically significant information for STRATTERA. cardiac abnormalities. (5.3) ® • Emergent Cardiovascular Symptoms – Patients should undergo STRATTERA (atomoxetine) capsules, for oral use prompt cardiac evaluation. (5.3) Initial U.S. Approval: 2002 • Effects on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate – Increase in blood WARNING: SUICIDAL IDEATION IN CHILDREN AND pressure and heart rate; orthostasis and syncope may occur. Use ADOLESCENTS with caution in patients with hypertension, tachycardia, or cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease. (5.4) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. • Emergent Psychotic or Manic Symptoms – Consider discontinuing • Increased risk of suicidal ideation in children or adolescents treatment if such new symptoms occur. (5.5) (5.1) • Bipolar Disorder – Screen patients to avoid possible induction of a • No suicides occurred in clinical trials (5.1) mixed/manic episode. (5.6) • Aggressive behavior or hostility should be monitored. (5.7) • Patients started on therapy should be monitored closely (5.1) • Possible allergic reactions, including anaphylactic reactions, angioneurotic edema, urticaria, and rash. (5.8) ------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE------------------------------- • Effects on Urine Outflow – Urinary hesitancy and retention may STRATTERA® is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor occur. (5.9) indicated for the treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder • Priapism – Prompt medical attention is required in the event of (ADHD). (1.1) suspected priapism. (5.10, 17) • Growth – Height and weight should be monitored in pediatric -----------------------DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION----------------------- patients. -

Choice of Drugs in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

RHEUMATOLOGY IN GENERAL PRACTICE 7 Those with predominant but never exclusive involvement of the terminal finger joint, usually associated with changes in the nail of the same finger; they are serologically negative. There may be a swollen finger with loss of the skin markings-a sort of dactylitis, again serologically negative. (2) Those with a much more severe process which produces loss of movement in the spine and changes in the sacroiliac joints much the same as those in ankylosing spondylitis; unlike ankylosing spondylitis, it produces severe deformity often with ankylosis in peripheral joints. Many of the finger joints become deformed and ankylosed. (3) Those cases indistinguishable from rheumatoid arthritis although the majority are sero-negative. The Stevens Johnson syndrome produces acute effusions, particularly in large joints. It is sometimes associated with the rash of erythema multiforme, always with ulceration in the mouth and genital tract; the mouth ulcers are accompanied by sloughing, unlike those of Beh9et's syndrome which we come to next. BehCet's syndrome, originally described as a combination of orogenital ulceration with relapsing iritis, is now expanded to include skin lesions, other eye lesions, lesions of the central nervous system, thrombophlebitis migrans, and arthropathy (occurring in 64 per cent). The onset is acute, often affecting only a single joint and settling without residual trouble. Choice of drugs in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis Dr Dudley Hart, M.D., F.R.C.P. (Consultant physician, Westminster Hospital and Medical School) There are many potential drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid disease, but what are we treating in this disorder? Pain in rheumatoid arthritis is but one of the symp- toms. -

SHARED CARE AGREEMENT ATOMOXETINE for ADULT ADHD

Shared Care Guideline Atomoxetine for Adult ADHD SHARED CARE AGREEMENT ATOMOXETINE for ADULT ADHD Version: Date: Author: Status: Comment: 1 01/2014 Tracey Green Draft Dr Saif Sharif Document Author Written by: Tracey Green Signed: Date: 15/07/2013 Job Title: Pharmacist Mental Health Approval DAC: 07/03/14 Trust Executive Committee date: April 2014 CCG Board date: April 2014 Review Date: March 2016 Effective Date: March 2014 Version Control History: Version: Date: Author: Status: Comment: 1 March 2014 Tracey Green Approved Dr Saif Sharif Shared Care Guideline February 2014 Isle of Wight NHS Trust 01983 524081 Lead Consultant Dr Saif Sharif Lead Nurse Lead Pharmacist Tracey Green Medicines Information 01983 534622 NB: This Shared Care Agreement relates to the Isle of Wight NHS Trust hereafter referred to as the Trust. This shared care guideline has been produced to support the seamless transfer of prescribing and patient monitoring from secondary to primary care and provides an information resource to support clinicians providing care to the patient. It does not replace discussion about sharing care on an individual patient basis. This guideline was prepared using information available at the time of preparation, but users should always refer to the manufacturer’s current edition of the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC or “data sheet”) for more details. The Trust holds full responsibility for any adverse events preventable by monitoring stated within the agreement at all times that prescribing continues within the limits set by the -

Literature Review of Prescription Analgesics in the Causal Path to Pain

Literature Review: Opioids and Death compiled by Bill Stockdale ([email protected]) This review is the result of searches for the terms opioid/opioid-related-disorders and death/ADE done in the PubMed database. This bibliography includes selected articles from the 1,075 found by searching during May, 2008, which represent key findings in the study of opioids. Articles for which there is no abstract are excluded. Also case reports and initial clinical trial reports are excluded. This is a compendium of all articles and do not lead to a specific target. There are three major topics developed in the literature as shown in this table of contents; • Topic One: Opioids in Causal Path to Death (page 1) o Prescription Drug Deaths (page 1) o Illicit Drug Deaths (page 30) o Neonatal Deaths (page 49) • Topic Two: Deaths in Palliative Care and Pain Treatment (page 57) • Topic Three: Pharmacology, Psychology, Origins of Abuse Relating to Death (page 72) • Bibliography (page 77) The three topics are presented below; each is followed in chronological order. Topic One: Opioids in Causal Path to Death Prescription Drug Deaths Karlson et al. describe differences in treatment of acute myocardial infarction, including different opioid use among men and women. The question whether women and men with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are treated differently is currently debated. In this analysis we compared pharmacological treatments and revascularization procedures during hospitalization and during 1 year of follow-up in 300 women and 621 men who suffered an AMI in 1986 or 1987 at our hospital. During hospitalization, the mean dose of morphine (+/- SD) during the first 3 days was higher in men compared to women (14.5 +/- 15.7 vs. -

Nevada Medicaid Formulary

Nevada Medicaid-Approved Preferred Drug List Effective August 15, 2021 Legend In each class, drugs are listed alphabetically by either brand name or generic name. Brand name drug: Uppercase in bold type Generic drug: Lowercase in plain type AL: Age Limit Restrictions DO: Dose Optimization Program GR: Gender Restriction OTC: Over the counter medication available with a prescription. (Prescribers please indicate OTC on the prescription) PA: Prior authorization is required. Prior authorization is the process of obtaining approval of benefits before certain prescriptions are filled. QL: Quantity limits; certain prescription medications have specific quantity limits per prescription or per month. SP: Specialty Pharmacy ST: Step therapy is required. You may need to use one medication before benefits for the use of another medication can be authorized. Drug Name Reference Notes *ADHD/ANTI-NARCOLEPSY/ANTI- OBESITY/ANOREXIANTS* *ADHD AGENT - SELECTIVE ALPHA ADRENERGIC AGONISTS*** clonidine hcl er oral tablet extended release Kapvay AL; QL 12 hour *ADHD AGENT - SELECTIVE NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITOR*** atomoxetine hcl oral capsule Strattera DO; AL; QL *AMPHETAMINE MIXTURES*** amphetamine-dextroamphet er oral capsule extended release 24 hour 10 mg, 15 mg, 5 Adderall XR DO; AL; QL mg amphetamine-dextroamphet er oral capsule extended release 24 hour 20 mg, 25 mg, 30 Adderall XR AL; QL mg amphetamine-dextroamphetamine oral Adderall DO; AL; QL tablet 10 mg, 12.5 mg, 15 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg amphetamine-dextroamphetamine oral Adderall AL tablet 20 mg, -

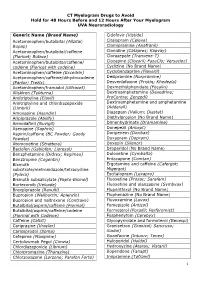

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

PCF4 Revised Monographs (Since Publication September 2011 to July 2014)

www.palliativedrugs.com PCF4 revised monographs (since publication September 2011 to July 2014) Monograph Chapter number Date updated 5HT3 antagonists Chapter 04 Correction Apr-13 5HT3 antagonists Chapter 04 Jun-14 Adjuvant analgesics Chapter 05 Jun-14 Alfentanil Chapter 05 May-14 Amitriptyline Chapter 04 Oct-13 Anaemia Chapter 09 Apr-14 Analgesic drugs and fitness to drive Chapter 19 Jun-14 Anaphylaxis Chapter 27 May-13 Anaphylaxis Chapter 27 Correction Oct-13 Anaphylaxis Chapter 27 Jul-14 Antacids Chapter 01 Sep-12 Antacids Chapter 01 Minor update Jun-14 Antibacterials in palliative care Chapter 06 Sep-12 Antibacterials in palliative care Chapter 06 Minor update Apr-14 Anticoagulants Chapter 02 Minor update Aug-13 Anticoagulants (new) Chapter 02 New May-13 Antidepressants Chapter 04 Oct-13 Anti-emetics Chapter 04 Jun-14 Anti-epileptics pre-synaptic calcium channel blockers Chapter 04 Discontinued May-14 Anti-epileptics sodium channel blockers Chapter 04 Discontinued May-14 Anti-epileptics Chapter 04 Merged monograph May-14 Antifibrinolytics Chapter 02 Aug-13 Antihistaminic antimuscarinic anti-emetics Chapter 04 Jun-14 Antimuscarinics Chapter 01 Correction Apr-13 Antimuscarinics Chapter 01 Apr-14 Antipsychotics Chapter 04 Jun-14 Antitussives Chapter 03 Mar-14 Artificial saliva Chapter 11 Jun-14 Ascorbic acid Chapter 09 Nov-12 Baclofen Chapter 10 Jun-14 Barrier products Chapter 12 Apr-14 Benzodiazepines Chapter 04 Jun-14 Bisphosphonates Chapter 07 Merged monograph Jun-14 Buprenorphine Chapter 05 Jun-13 Buprenorphine Chapter 05 Jun-14 -

Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders Second Edition WORK GROUP ON SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Herbert D. Kleber, M.D., Chair Roger D. Weiss, M.D., Vice-Chair Raymond F. Anton Jr., M.D. To n y P. G e o r ge , M .D . Shelly F. Greenfield, M.D., M.P.H. Thomas R. Kosten, M.D. Charles P. O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D. Bruce J. Rounsaville, M.D. Eric C. Strain, M.D. Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D. Grace Hennessy, M.D. (Consultant) Hilary Smith Connery, M.D., Ph.D. (Consultant) This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in August 2006. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available in the Psychiatric Practice section of the APA web site at www.psych.org. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M.