Impact of ADHD and Its Treatment on Substance Abuse in Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomoxetine: a New Pharmacotherapeutic Approach in the Management of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

i26 Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.2004.059386 on 21 January 2005. Downloaded from Atomoxetine: a new pharmacotherapeutic approach in the management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder J Barton ............................................................................................................................... Arch Dis Child 2005;90(Suppl I):i26–i29. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059386 Atomoxetine is a novel, non-stimulant, highly selective lifespan including a potential requirement for lifelong treatment.4 Because of the limitations of noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor that has been studied for existing treatments and the paradigm shift in use in the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity thinking about the management of ADHD, there disorder (ADHD). Data from clinical trials show it to be well is an interest in the development of new pharmacological treatments. tolerated and effective in the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults. Improvements were seen ATOMOXETINE HYDROCHLORIDE: A not only in core symptoms of ADHD, but also in broader NOVEL TREATMENT FOR ADHD social and family functioning and self esteem. Once-daily Atomoxetine is the first non-stimulant to be approved for the treatment of ADHD and the first dosing of atomoxetine has been shown to be effective in drug to be licensed for the treatment of ADHD in providing continuous symptom relief. Atomoxetine does adults.5 Atomoxetine was licensed in the US in not appear to have abuse potential and is associated with November 2002 and in the UK in May 2004. At the time of writing, it is under consideration for a benign side effect profile. The development of licensing by the regulatory authorities in a atomoxetine thus represents an important advance in the number of other countries. -

STRATTERA Safely and Effectively

1 HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION serious cardiac problems that may place them at increased These highlights do not include all the information needed to use vulnerability to its noradrenergic effects. Consideration should be STRATTERA safely and effectively. See full prescribing given to not using STRATTERA in adults with clinically significant information for STRATTERA. cardiac abnormalities. (5.3) ® • Emergent Cardiovascular Symptoms – Patients should undergo STRATTERA (atomoxetine) capsules, for oral use prompt cardiac evaluation. (5.3) Initial U.S. Approval: 2002 • Effects on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate – Increase in blood WARNING: SUICIDAL IDEATION IN CHILDREN AND pressure and heart rate; orthostasis and syncope may occur. Use ADOLESCENTS with caution in patients with hypertension, tachycardia, or cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease. (5.4) See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. • Emergent Psychotic or Manic Symptoms – Consider discontinuing • Increased risk of suicidal ideation in children or adolescents treatment if such new symptoms occur. (5.5) (5.1) • Bipolar Disorder – Screen patients to avoid possible induction of a • No suicides occurred in clinical trials (5.1) mixed/manic episode. (5.6) • Aggressive behavior or hostility should be monitored. (5.7) • Patients started on therapy should be monitored closely (5.1) • Possible allergic reactions, including anaphylactic reactions, angioneurotic edema, urticaria, and rash. (5.8) ------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE------------------------------- • Effects on Urine Outflow – Urinary hesitancy and retention may STRATTERA® is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor occur. (5.9) indicated for the treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder • Priapism – Prompt medical attention is required in the event of (ADHD). (1.1) suspected priapism. (5.10, 17) • Growth – Height and weight should be monitored in pediatric -----------------------DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION----------------------- patients. -

SHARED CARE AGREEMENT ATOMOXETINE for ADULT ADHD

Shared Care Guideline Atomoxetine for Adult ADHD SHARED CARE AGREEMENT ATOMOXETINE for ADULT ADHD Version: Date: Author: Status: Comment: 1 01/2014 Tracey Green Draft Dr Saif Sharif Document Author Written by: Tracey Green Signed: Date: 15/07/2013 Job Title: Pharmacist Mental Health Approval DAC: 07/03/14 Trust Executive Committee date: April 2014 CCG Board date: April 2014 Review Date: March 2016 Effective Date: March 2014 Version Control History: Version: Date: Author: Status: Comment: 1 March 2014 Tracey Green Approved Dr Saif Sharif Shared Care Guideline February 2014 Isle of Wight NHS Trust 01983 524081 Lead Consultant Dr Saif Sharif Lead Nurse Lead Pharmacist Tracey Green Medicines Information 01983 534622 NB: This Shared Care Agreement relates to the Isle of Wight NHS Trust hereafter referred to as the Trust. This shared care guideline has been produced to support the seamless transfer of prescribing and patient monitoring from secondary to primary care and provides an information resource to support clinicians providing care to the patient. It does not replace discussion about sharing care on an individual patient basis. This guideline was prepared using information available at the time of preparation, but users should always refer to the manufacturer’s current edition of the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC or “data sheet”) for more details. The Trust holds full responsibility for any adverse events preventable by monitoring stated within the agreement at all times that prescribing continues within the limits set by the -

Nevada Medicaid Formulary

Nevada Medicaid-Approved Preferred Drug List Effective August 15, 2021 Legend In each class, drugs are listed alphabetically by either brand name or generic name. Brand name drug: Uppercase in bold type Generic drug: Lowercase in plain type AL: Age Limit Restrictions DO: Dose Optimization Program GR: Gender Restriction OTC: Over the counter medication available with a prescription. (Prescribers please indicate OTC on the prescription) PA: Prior authorization is required. Prior authorization is the process of obtaining approval of benefits before certain prescriptions are filled. QL: Quantity limits; certain prescription medications have specific quantity limits per prescription or per month. SP: Specialty Pharmacy ST: Step therapy is required. You may need to use one medication before benefits for the use of another medication can be authorized. Drug Name Reference Notes *ADHD/ANTI-NARCOLEPSY/ANTI- OBESITY/ANOREXIANTS* *ADHD AGENT - SELECTIVE ALPHA ADRENERGIC AGONISTS*** clonidine hcl er oral tablet extended release Kapvay AL; QL 12 hour *ADHD AGENT - SELECTIVE NOREPINEPHRINE REUPTAKE INHIBITOR*** atomoxetine hcl oral capsule Strattera DO; AL; QL *AMPHETAMINE MIXTURES*** amphetamine-dextroamphet er oral capsule extended release 24 hour 10 mg, 15 mg, 5 Adderall XR DO; AL; QL mg amphetamine-dextroamphet er oral capsule extended release 24 hour 20 mg, 25 mg, 30 Adderall XR AL; QL mg amphetamine-dextroamphetamine oral Adderall DO; AL; QL tablet 10 mg, 12.5 mg, 15 mg, 5 mg, 7.5 mg amphetamine-dextroamphetamine oral Adderall AL tablet 20 mg, -

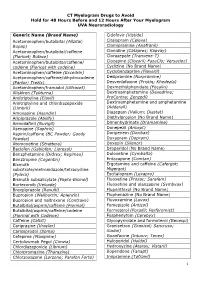

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders Second Edition

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Substance Use Disorders Second Edition WORK GROUP ON SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Herbert D. Kleber, M.D., Chair Roger D. Weiss, M.D., Vice-Chair Raymond F. Anton Jr., M.D. To n y P. G e o r ge , M .D . Shelly F. Greenfield, M.D., M.P.H. Thomas R. Kosten, M.D. Charles P. O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D. Bruce J. Rounsaville, M.D. Eric C. Strain, M.D. Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D. Grace Hennessy, M.D. (Consultant) Hilary Smith Connery, M.D., Ph.D. (Consultant) This practice guideline was approved in December 2005 and published in August 2006. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available in the Psychiatric Practice section of the APA web site at www.psych.org. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. -

Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Substance Use Disorders

ADVISORY Behavioral Health Is Essential To Health • Prevention Works • Treatment Is Effective • People Recover Adults With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Substance Use Disorders Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Which ADHD symptoms are most prominent is one of the most common childhood mental varies with age and circumstance. The hyper- disorders, and it can persist through adolescence activity symptoms are usually the most noticeable and adulthood. The medications most commonly during the preschool and elementary school used to treat ADHD are stimulants, and survey years. Late in elementary and middle school, the inattention symptoms come to the fore.2 data show that abuse of prescription stimulants Among adolescents, hyperactivity may be limited is on the rise. This Advisory discusses the co- to fidgeting and be experienced as feelings of occurrence of ADHD and substance use disorders jitteriness and impatience. DSM-5 notes that (SUDs), the misuse of prescription stimulants, ADHD symptoms wax and wane depending and treatment and prevention approaches to on the circumstance. Close supervision, a new these problems. setting, an engrossing activity, or frequent rewards for appropriate behavior may make symptoms go The Definition of ADHD away temporarily.1 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Adult ADHD Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5),1 the essential feature of ADHD is a persistent For many years, experts believed that children 3 pattern of inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity and adolescents outgrew ADHD. However, (they are grouped together), or both that interferes research that followed children with ADHD into adulthood showed that the condition can persist with normal functioning and development.1 into adulthood. -

Ketamine: a Novel Antidepressant with a Fast Onset of Action?† COMMENTARY ON… COCHRANE CORNER Katharine Smith & Mary Jane Attenburrow

BJPsych Advances (2016), vol. 22, 216–221 doi: 10.1192/apt.22.4.216 ROUND THE CORNER Ketamine: a novel antidepressant with a fast onset of action?† COMMENTARY ON… COCHRANE CORNER Katharine Smith & Mary Jane Attenburrow Katharine Smith is an honorary For bipolar depression, the treatment challenge SUMMARY consultant psychiatrist at the is even greater. There is scarce evidence that National Institute for Health Glutamate receptor modulators, including antidepressants are effective as a first-line Research (NIHR) Oxford cognitive ketamine, are possible candidates for new health Clinical Research Facility treatment (Sidor 2012), and mood instability is an antidepressants with a novel mode of action. and Oxford University Department additional challenge. Current recommendations The pair of reviews discussed in this month’s of Psychiatry. Mary Jane (Kendall 2014) focus on the use of quetiapine; Attenburrow is Clinical Lead at Round the Corner considered their use in treating the NIHR Oxford cognitive health unipolar major depression and bipolar depression. lamotrigine, fluoxetine plus olanzapine and Clinical Research Facility, a Senior Promising results were seen for ketamine, but lithium are also recommended. A recent trial Research Fellow at Oxford University further studies are needed, in particular to (CEQUEL) demonst ra ted that there may be benefit Department of Psychiatry and an investigate whether the benefits are sustained in the combination of lamotrigine with quetiapine honorary consultant psychiatrist. Correspondence Dr Katharine or can be extended by repeated or adjunctive (Geddes 2016). Smith, NIHR Oxford cognitive health treatment, whether ketamine is effective in Although the differences in treatment response Clinical Research Facility, Warneford treatment resistance, whether other modes of between unipolar and bipolar depression Hospital, Oxford OX3 7JX, UK. -

Stratteraä (Atomoxetine Hcl)

1 [FDA APPROVED PPI FOR NDA 21-411/S-001 ATTACHMENT TO APPROVAL LETTER] NL 3740 AMP INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS OR THEIR PARENTS OR CAREGIVERS STRATTERAä (atomoxetine HCl) Read this information before you start taking STRATTERA (Stra-TAIR-a). Read this information you get each time you get more STRATTERA. There may be new information. This information does not take the place of talking to your doctor about your medical condition or treatment. What is STRATTERA? STRATTERA is a non-stimulant medicine used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). STRATTERA contains atomoxetine hydrochloride, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Your doctor has prescribed this medicine as part of an overall treatment plan to control your symptoms of ADHD. What is ADHD? ADHD has 3 main types of symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness. Symptoms of inattention include not paying attention, making careless mistakes, not listening, not finishing tasks, not following directions, and being easily distracted. Symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsiveness include fidgeting, talking excessively, running around at inappropriate times, and interrupting others. Some patients have more symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsiveness while others have more symptoms of inattentiveness. Some patients have all 3 types of symptoms. Symptoms of ADHD in adults may include a lack of organization, problems starting tasks, impulsive actions, daydreaming, daytime drowsiness, slow processing of information, difficulty learning new things, irritability, lack of motivation, sensitivity to criticism, forgetfulness, low self-esteem, and excessive effort to maintain some organization. The symptoms shown by adults who primarily have attention problems but not hyperactivity have been commonly described as Attention-Deficit Disorder (ADD). -

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

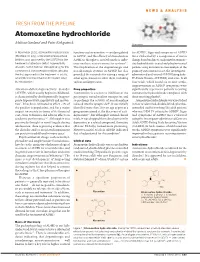

Atomoxetine Hydrochloride

NEWS & ANALYSIS FRESH FROM THE PIPELINE Atomoxetine hydrochloride Melissa Garland and Peter Kirkpatrick Atomoxetine In November 2002, atomoxetine hydrochloride functions such as attention — are dysregulated for ADHD9.Signs and symptoms of ADHD (Strattera; Eli Lilly), a noradrenaline-reuptake in ADHD, and the efficacy of stimulants in were evaluated by a comparison of mean inhibitor, was approved by the US FDA for the ADHD is thought to result from their influ- change from baseline to endpoint for atomoxe- treatment of attention-deficit–hyperactivity ence on these neurotransmitter systems4,5. tine hydrochloride-treated and placebo-treated disorder. As the first non-stimulant drug for this The implication of the dopaminergic and patients using an intent-to-treat analysis of the common but controversial condition, and also noradrenergic systems in ADHD has also primary outcome measure, the investigator- the first approved for the treatment of adults, provided the rationale for testing a range of administered and -scored ADHD Rating Scale- what influence has it had on the market since other agents known to affect them, including IV-Parent Version (ADHDRS) total score. In all its introduction? various antidepressants. four trials, which lasted six to nine weeks, improvements in ADHD symptoms were Attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder Drug properties significantly superior in patients receiving (ADHD), which usually begins in childhood, Atomoxetine is a selective inhibitor of the atomoxetine hydrochloride compared with is characterized by -

List of Formulary Drug Removals

July 2021 Formulary Drug Removals Below is a list of medicines by drug class that have been removed from your plan’s formulary. If you continue using one of the drugs listed below and identified as a Formulary Drug Removal, you may be required to pay the full cost. If you are currently using one of the formulary drug removals, ask your doctor to choose one of the generic or brand formulary options listed below. Category Formulary Drug Formulary Options Drug Class Removals Acromegaly SANDOSTATIN LAR SOMATULINE DEPOT SIGNIFOR LAR SOMAVERT Allergies dexchlorpheniramine levocetirizine Antihistamines Diphen Elixir RyClora CARBINOXAMINE TABLET 6 MG Allergies BECONASE AQ flunisolide spray, fluticasone spray, mometasone spray, DYMISTA Nasal Steroids / Combinations OMNARIS QNASL ZETONNA Anticonvulsants topiramate ext-rel capsule carbamazepine, carbamazepine ext-rel, clobazam, divalproex sodium, (generics for QUDEXY XR only) divalproex sodium ext-rel, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lamotrigine ext-rel, levetiracetam, levetiracetam ext-rel, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, phenytoin sodium extended, primidone, rufinamide, tiagabine, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide, FYCOMPA, OXTELLAR XR, TROKENDI XR, VIMPAT, XCOPRI BANZEL SUSPENSION clobazam, lamotrigine, rufinamide, topiramate, TROKENDI XR ONFI SABRIL vigabatrin ZONEGRAN carbamazepine, carbamazepine ext-rel, divalproex sodium, divalproex sodium ext-rel, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lamotrigine ext-rel, levetiracetam, levetiracetam ext-rel, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, phenytoin sodium