Kritika Vol. 14, No.1 31-58

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Federation. Assistance in The

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] 1.0 ~j ·~ w 111 ~ . ·~ 12.2 ~ -~ ...... 111.1 I!' :~: 25 4 6 111111. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Russian Federation: Explosion

DREF operation n° MDRRU004 Russian Federation: 24 August 2009 Explosion The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 29,973 (USD 28,127 or EUR 19,762) has been allocated from the International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the National Society in delivering immediate assistance to some 2,100 beneficiaries. Summary: An explosion at the Sayano- Shushenskaya hydropower station in eastern Siberia killed 69 people and left another 6 people missing. One settlement close to the station lost its water supply due to the oil slick in the Yenisei river. The Russian Red Cross will distribute bottled water among the most vulnerable people and provide psychosocial support to the families of power station workers affected by the explosion. Consequences of the blast in the turbine room at Sayano- Shushenskaya hydropower station. Photo: Russian Ministry of Emergencies This operation is expected to be implemented over four months, and will therefore be completed by 22 December 2009; a Final Report will be made available by 22 March 2010. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. <click here for the DREF budget, here for contact details, or here to view the map of the affected area> The situation On 17 August 2009 an explosion at Sayano- Shushenskaya hydropower station in eastern Siberia destroyed the walls and the ceiling of a turbine room which then flooded. -

ALTAI SPECIAL on the Trail of Silk Route: Pilgrimage to Sumeru, Altai K

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 18 Nos. 3-4 July-December 2014 ALTAI SPECIAL On the Trail of Silk Route: Pilgrimage to Sumeru, Altai K. Warikoo Eurasian Philosophy of Culture: The Principles of Formation M. Yu. Shishin Altai as a Centre of Eurasian Cooperation A.V. Ivanov, I.V. Fotieva and A.V. Kremneva Altai – A Source of Spiritual Ecology as a Norm of Eurasian Civilization D.I.Mamyev Modeling the Concept “Altai” O.A. Staroseletz and N.N. Simonova The Phenomenon Altai in the System of World Culture E.I. Balakina and E.E. Balakina Altai as One of the Poles of Energy of the Geo-Cultural Phenomenon “Altai-Himalayas” I.A. Zhernosenko Altaian and Central Asian Beliefs about Sumeru Alfred Poznyakov Cross Border Tourism in Altai Mountain Region A.N. Dunets HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K. WARIKOO Guest Associate Editor : I.A. ZHERNOSENKO © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 500.00 Annual (Individual) -

Assessing the Interrelation Between Socio-Economic and Innovative-Technological Development, Institutional Conditions and Urbanization Processes in the Resource-Based

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences … (201… …) 000 ~ ~ ~ УДК 332.055:325.111(571.51) Assessing the Interrelation between Socio-Economic and Innovative-Technological Development, Institutional Conditions and Urbanization Processes in the Resource-Based Regions Using Dynamic Economic and Statistical Models Anna Semenova, Evgenia Bukharova, Irina Popelnitskaya, Natalia Nepomnyashchaya and Veronica Razumovskaya* Siberian Federal University 79/10 Svobodny Prospekt, Krasnoyarsk, 660041 Russia Received 12.11.2018, received in revised form 16.11.2018, accepted 19.11.2018 Relying on the current terms and patterns of development of any given region, strategic goals of the country’s spatial development and its institutional environment, urbanization impact on the economic and innovative-technological modernization of the territory is not identical. This research aims statistic data-based measurement of quantitative indicators which determine interrelation between the process of urbanization and dimensions for economic, innovative- technological and socio-cultural development of the regions with resource economy. In the framework of system analysis urbanized territories are considered as multi-component complex systems. Today’s tendencies in the practice of forecasting, planning and monitoring urbanized territories are focused on tackling a multi-criteria and multi-dimensional problem with a complicated system of constraints which is, traditionally, not judgment-based. This paper observes takes on modeling interrelation between the factors of socio-economic development and the level of urbanization in municipal settlements in the resource region – Krasnoyarskiy Krai – and on integrated ranking of urbanized territories based on dynamic changes of these factors. Keywords: resource-based economy, socio-economic and ecological development of urbanized territories, spatial development, living comfort, dynamic economic and statistical modeling, institutional conditions. -

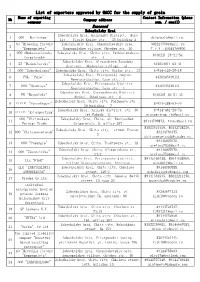

List of Exporters Approved by GACC for the Supply of Grain Name of Exporting Contact Infromation (Phone № Company Address Company Num

List of exporters approved by GACC for the supply of grain Name of exporting Contact Infromation (phone № Company address company num. / email) Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. 1st , Vitaly Kozlov str., 25 building A AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, [email protected] 2 "Komsomolets" Komsomolskoe village, Oktober str. 30 Тел.:89243788800 OOO «Bukachachinsky Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya 3 8(3022) 23-21-54 Izvestyank» str., 4 Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky 4 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 district,. Mankechur village, ul. 5 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, 6 PSK ''Pole'' 8(30243)30111 Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, 7 OOO "Mysovaya" 8(30243)30111 Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, 8 PK "Baygulsky" 8(3026) 56-51-35 Baygul, Shkolnaya str., 6 Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 9 ООО "ForceExport" 8-924-388-67-74 30 building, 7 Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 8-914-461-28-74 10 ООО "Eсospectrum" let Pobedi, 11 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita, ul. Kostyushko- 11 89144709873, [email protected] Foreign Trade Grigorovich, 5, office 207 83022415459, 89242728229, Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, street Frunze, 12 OOO "Chitazoovetsnab" 89243739475, 3 [email protected] 89148007070, 13 OOO "PromAgro" Zabaykalsky -

Clean Energy Sources: Insights from Russia

Article Clean Energy Sources: Insights from Russia Elizaveta Gavrikova1, Yegor Burda1,*, Vladimir Gavrikov2, Ruslan Sharafutdinov2, Irina Volkova1, Marina Rubleva2 and Daria Polosukhina2 1 Department of General and Strategic Management, National Research University Higher School of Economics, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (E.G.); [email protected] (I.V.) 2 Institute of Ecology and Geography, Siberian Federal University, 660041 Krasnoyarsk, pr. Svobodny, 79, Russia; [email protected] (V.G.); [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (D.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-915-286-8934 Received: 1 April 2019; Accepted: 23 April 2019; Published: 1 May 2019 Abstract: The paper is devoted to the assessment of the prospects of implementing clean energy sources in Russia, where the current energy policy goal is to increase the role of renewable and clean energy sources. The research is based on data from the Krasnoyarsk Region as one of the largest territories but also as a representative model of Russia. The aim of the study is to identify where and which renewable energy source (solar, wind, hydro and nuclear) has the highest potential. The novelty of our research lies in its holistic nature: authors consider both geographical and technical potential for renewable energy sources development as well as prospective demand for such resources, while previous research is mostly focused on specific aspects of renewable energy development. We also consider the level of air pollution as an important factor for the development of renewable energy sources. The results of the study show that there is a strong potential for clean energy sources in the Krasnoyarsk Region. -

List of Exporters Interested in Supplying Grain to China

List of exporters interested in supplying grain to China № Name of exporting company Company address Contact Infromation (phone num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1st , Vitaly Kozlov str., 25 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. building A 2 OOO ''Zelenyi List'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Butina str., 93 8-914-469-64-44 AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, Komsomolskoe village, Oktober str. 3 [email protected] Тел.:89243788800 "Komsomolets" 30 4 OOO «Bukachachinsky Izvestyank» Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya str., 4 8(3022) 23-21-54 Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky district,. Mankechur village, ul. 5 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 Tsentralnaya 6 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 7 PSK ''Pole'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 8 OOO "Mysovaya" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 9 OOO "Urulyungui" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Dosatuy,Lenin str., 19 B 89245108820 10 OOO "Xin Jiang" Zabaykalsky Krai,Urban-type settlement Priargunsk, Lenin str., 2 8-914-504-53-38 11 PK "Baygulsky" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, Baygul, Shkolnaya str., 6 8(3026) 56-51-35 12 ООО "ForceExport" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 30 building, 7 8-924-388-67-74 13 ООО "Eсospectrum" Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 let Pobedi, 11 8-914-461-28-74 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya -

HYGIENIC ASSESSMENT of DRINKING WATER QUALITY and HEALTH RISKS for KRASNOYARSK REGION POPULATION D.V. Goryaev, I.V. Tikhonova

Hygienic assessment of drinking water quality and risks to public health in krasnoyarsk region… UDC 614 DOI: 10.21668/health.risk/2016.3.04 HYGIENIC ASSESSMENT OF DRINKING WATER QUALITY AND HEALTH RISKS FOR KRASNOYARSK REGION POPULATION D.V. Goryaev, I.V. Tikhonova, N.N. Torotenkova Federal Service for Surveillance over Consumer Rights Protection and Human Well-being in the Krasnoyarsk Region, 21 Karatanova St., Krasnoyarsk, 660049, Russian Federation The article deals with hygienic assessment of water sources quality for the centralized drinking water supply for resi- dential use in Krasnoyarsk region. The authors have detected violation of hygienic standards, as per such parameters as iron (iron content at the level of 1.8 mg/dm3 or 6MPC has been fixed); fluorine (up to 6MPC); ammonia and ammonium nitrogen (up to 2MPC), nitrates (up to 5MPC); organochlorine compounds (chloroform, carbon tetrachloride – up to 5MPC), manga- nese (up to 5.5MPC), aluminum (up to 2MPC). Such carcinogenic impurities, as benz(a)pyrene, cadmium, arsenic, nickel and lead were detected in water in high concentrations. It’s been found that total lifetime carcinogenic health risk for the cities and districts residents in Krasnoyarsk region, due to carcinogenic chemicals ingestion with drinking water, in 22 areas is being assessed as negligible, and doesn’t require an additional mitigation measures. In 23 areas carcinogenic risk ranges within 1.0e-6 – 1.0e-5, which corresponds to criteria for risk acceptance. In 9 areas (Borodino, Lesosibirsk towns, Yeniseisk, Kazachinskiy, Partisanskiy, Pirovskiy, Rybinskiy, Sayanskiy, Uyarskiy districts) the determined lifetime individual carcino- genic risk level ranges between 1.0e-5 to 2.0e-4, which is inacceptable for the population in general. -

Ground Beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) and Zoodiagnostics of Ecological Succession on Technogenic Catenas of Brown Coal Dumps in the KAFEC Area (Krasnoyarsk Krai) V

ISSN 1062-3590, Biology Bulletin, 2019, Vol. 46, No. 5, pp. 500–509. © Pleiades Publishing, Inc., 2019. Russian Text © The Author(s), 2019, published in Izvestiya Akademii Nauk, Seriya Biologicheskaya, 2019, No. 5, pp. 533–543. Ground Beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) and Zoodiagnostics of Ecological Succession on Technogenic Catenas of Brown Coal Dumps in the KAFEC area (Krasnoyarsk Krai) V. G. Mordkovicha and I. I. Lyubechanskiia, * aInstitute of Systematics and Animal Ecology, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, 630091 Russia *e-mail: [email protected] Received March 4, 2019; revised April 15, 2019; accepted April 15, 2019 Abstract—The population of ground beetles on artificial catenas of dumps of brown-coal pits in Krasnoyarsk krai (dump age of one month, seven years, and 25 years) was investigated. The material was collected in the eluvial, transitional, and accumulative positions of each catena. The species diversity and activity of ground beetles after 25 years of succession in all catena positions do not reach the state of natural communities. The rate and direction of succession of the ground beetle taxocenes differed significantly depending on their relief position. The appearance of species typical of zonal forest–steppe ecosystems began after seven years of suc- cession. In the accumulative position, succession developed more slowly than in the eluvial and transitional positions, where ruderal carabid species were gradually replaced by meadow mesophilous, and then by mesoxerophilous species. After 25 years, the taxocene of ground beetles in the accumulative position became similar not to the herb, but to the wood communities of the forest–steppe. DOI: 10.1134/S106235901905008X INTRODUCTION Interest in the study of biota successions on dumps, in particular, of coal enterprises, arose in the 1960s The most important reason for the reduction of (Dunger, 1968). -

List of Exporters Approved by GACC for the Supply of Grain Contact Infromation (Phone № Name of Exporting Company Company Address Num

List of exporters approved by GACC for the supply of grain Contact Infromation (phone № Name of exporting company Company address num. / email) Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1st , Vitaly 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. Kozlov str., 25 building A AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, Komsomolskoe [email protected] 2 "Komsomolets" village, Oktober str. 30 Тел.:89243788800 OOO «Bukachachinsky 3 Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya str., 4 8(3022) 23-21-54 Izvestyank» Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky district,. 4 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 Mankechur village, ul. Tsentralnaya 5 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, Novotsuruhaytuy, 6 PSK ''Pole'' 8(30243)30111 Lazo str., 1 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Novotsuruhaytuy, 7 OOO "Mysovaya" 8(30243)30111 Lazo str., 1 Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, Baygul, 8 PK "Baygulsky" 8(3026) 56-51-35 Shkolnaya str., 6 Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 30 9 ООО "ForceExport" 8-924-388-67-74 building, 7 8-914-461-28-74 10 ООО "Eсospectrum" Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 let Pobedi, 11 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya Foreign Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita, ul. Kostyushko-Grigorovich, 5, 11 89144709873, [email protected] Trade Company" office 207 83022415459, 89242728229, 12 OOO "Chitazoovetsnab" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, street Frunze, 3 89243739475, [email protected] 89148007070, 13 -

Use of Panel Data for Assessing Socio-Economic Situation in the Northern Regions of Krasnoyarsk Krai

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 12 (2017 10) 1905-1915 ~ ~ ~ УДК 314 Use of Panel Data for Assessing Socio-Economic Situation in the Northern Regions of Krasnoyarsk Krai Anna R. Semenova* and Irina M. Popelnitskaya Siberian Federal University 79 Svobodny, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia Received 12.10.2017, received in revised form 22.10.2017, accepted 16.11.2017 The development of resource regions in Siberia including the Northern Areas of Krasnoyarsk Krai falls within the scope of priority economic and geopolitical interests of this country. The strategic development of the resource regions in Northern Arctic Territories squares off against a set of particularly urgent environmental, economic and social problems such as a declining quality of life, labor shortages, increasing transformation rate of the resource-based potential. In this regard, to make the resource regions’ development management even more efficient it is necessary to implement up-top scientific methods and mechanisms on decision-making, forecasting and monitoring of the regional economy. The research novelty is related to formulation of econometric techniques and spatial economics model system relying on panel (longitudinal) studies for assessing spatial development of the regional economy in general and its elements in particular. Firstly, this approach measures how not merely system changes, but also certain management decisions impact the rate of regional development, and secondly – allows for statistically valid matching among different Northern Areas in Russia and other countries. An integrated initial sampling includes urban areas and 56 municipal districts of Krasnoyarsk Krai in 2007 – 2015.