Studies of EIA Practice in Developing Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Forecasting and Warning Networkperformanceapprmsal 2008

FLOOD FORECASTING AND WARNING NETWORKPERFORMANCEAPPRMSAL 2008 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION FLOOD FORECAST MONITORING DIRECTORATE NEW DELHI - 110066 Feb,2010 PREFACE Central Water Commission had made a small beginning in Flood Forecasting & Warning service in India in November 1958 with .one forecasting station at Delhi, the national capital, on the river Yamuna. Today, its network of Flood Forecasting and Warning Stations has gradually extended over the years and covers almost all the major inter-state flood prone river basins throughout the country. The network comprised of 175 Flood Forecasting Stations including 28 inflow forecast during the year 2008, in 9 major river basins and 71 sub basins of the country. It covered 15 states besides NCT Delhi and UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli. The flood forecasting activities of the Commission are being performed every year from May to October through its 21 field divisions which issue flood forecasts and warnings to the civil authorities of the states as well as to other organizations of the central & state governments, as and when the river water level touches or is expected to touch the warning level at the flood forecasting stations. The flood season 2008 witnessed unprecedented flood events in recent history. Both the river Subarnarekha at Rajghat and river Ghaghra at Ayodhya had once again recorded in 2008 a fresh "unprecedented Flood", for the second consecutive year after experiencing a similar event in 2007. In addition, "unprecedented Flood" was recorded on river Puthimari at N.H.Road crossing, river Devi, a distributory of river Mahanadi at Alipingal and Gharghra at Elgin Bridge. -

MMIW" 1. (8Iiira)

..nth Ser... , Vol. ru, No. 11 ...,. July 1., 200t , MMIW" 1. (8IIIra) LOK SABHA DEBATES (Engllah Version) Second Seulon (FourtMnth Lok Sabha) (;-. r r ' ':1" (Vol. III Nos. 11 to 20) .. contains il'- r .. .Ig A g r ~/1'~.~.~~: LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price : Rs. 50.00 EDITORIAL BOARD G.C. MalhotrII Secretary-General Lok Sabha Anand B. Kulkllrnl Joint Secretary Sharda Prued Principal Chief Editor telran Sahnl Chief Editor Parmnh Kumar Sharma Senior Editor AJIt Singh Yed8v Editor (ORIOINAL ENOUSH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGUSH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE.TREATED AS AUTHORITA11VE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION THEREOF) CONTENTS ,.. (Fourteenth Serles. Vol. III. Second Session. 200411926 (Saka) No. 11. Monday. July 19. 2OO4IAudha, 28. 1121 CSU-) Sua.lECT OBITUARY REFERENCE ...... ...... .......... .... ..... ............................................ .......................... .................................... 1·2 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question No. 182-201 ................................................................. ................ ................... ...................... 2-36 Unstarred Question No. 1535-1735 .................... ..... ........ ........ ...... ........ ......... ................ ................. ........ ......... 36-364 ANNEXURE I Member-wise Index to Starred List of Ouestions ...... ............ .......... .... .......... ........................................ ........... 365 Member-wise Index to Unstarred Ust of Questions ........................................................................................ -

Flood Forecasting and Warning Network Performance Appraisal Report 2014

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION FLOOD FORECAST MONITORING DIRECTORATE People being rescued by the army personnels and local people after the floods at Tangpura in Srinagar. FLOOD FORECASTING AND WARNING NETWORK PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL REPORT 2014 NEW DELHI – 110066 March 2016 Member (RM) Central Water Commission Sewa Bhawan, R. K. Puram New Delhi-110066 PREFACE Central Water Commission had started Flood Forecasting & Warning service in India in November 1958 by setting one forecasting station at Old Delhi Bridge, for the national capital, on the river Yamuna. Today, its network of Flood Forecasting and Warning Stations gradually extended covering almost all the major inter-state flood prone river basins throughout the country. It comprises of 175 Flood Forecasting Stations including 28 inflow forecast in 9 major river basins and 71 sub basins of the country. It covers 16 states besides NCT Delhi and UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli. The flood forecasting activities of the Commission are being performed every year from May to October through its 20 field divisions which issue flood forecasts and warnings to the civil authorities of the states as well as to other organizations of the central & state governments, as and when the river water level touches or is expected to cross the warning level at the flood forecasting stations. Inflow Forecasts are issued for 28 reservoir/dam/barrages. The forecasts are formulated whenever the inflow into the dam exceeds the threshold value fixed by the respective project authorities for reservoir regulation as well as flood moderation. The flood season 2014 witnessed unprecedented flood events at 2 stations in the rivers Ghaghra and Rapti in the country. -

The Mindlessness Called River Linking Proposals

It does not rain on Rivers alone; Rivers don’t carry water alone. The Mindlessness called River Linking Proposals May 2003 South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People SANDRP New Delhi [email protected] It does not rain in Rivers alone; Rivers don’t carry water alone. The Mindlessness called River Linking Proposals Index GOI Resolution on Constitution of Task Force 3 Supreme Court Orders on River Linking issues 4 SC remark was only a suggestion 5 Relevant Extracts from Speech of President of India on 14.08.02 5 R Iyer on SC order 5 River Link in Parliament 6 River Basins in India 8 River Link Proposals: Some Basic Information 10 Govt’s blue ribbon commission is sceptical about River Link Proposals 11 Let’s have our feet on Ground, Mr Prabhu 13 HOW OPPOSITION IS MOUNTING 16 Famine of Good Deeds and Ideas 18 An Appeal by Concerned Scientists of W Bengal 19 Can we manage existing systems? 20 Govt of India in SC 21 Rising Scepticism about River Link Rhetoric 22 Trade Union in Maharashtra against River Link Proposals 23 Water & Constitution of India: Aspects of Federalism 24 Why River Linking is such a mindless idea? 27 Why is the River Linking Proposal being pushed? 29 A Report in Bihar Vidhan Parishan meeting on River Linking 31 Who will remind PM about his words on Rain Water Harvesting? 34 SANDRP 2 May 2003 It does not rain in Rivers alone; Rivers don’t carry water alone. The Mindlessness called River Linking Proposals GOVERNMENT OF INDIA RESOLUTION ON CONSTITUTION OF THE TASK FORCE ON RIVER LINKING RESOLUTION NO.2/21/2002-BM; MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES; New Delhi, the 13th Dec 2002 The Ministry of Water Resources (then known as Ministry of Irrigation) in the year 1980 formulated a National Perspective Plan for water resources development by transferring water from water surplus basins to water deficit basins/regions by inter-linking of rivers. -

Reconciling Drainage and Receiving Basin Signatures of the Godavari River System

Biogeosciences, 15, 3357–3375, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-3357-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Reconciling drainage and receiving basin signatures of the Godavari River system Muhammed Ojoshogu Usman1, Frédérique Marie Sophie Anne Kirkels2, Huub Michel Zwart2, Sayak Basu3, Camilo Ponton4, Thomas Michael Blattmann1, Michael Ploetze5, Negar Haghipour1,6, Cameron McIntyre1,6,7, Francien Peterse2, Maarten Lupker1, Liviu Giosan8, and Timothy Ian Eglinton1 1Geological Institute, ETH Zürich, Sonneggstrasse 5, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland 2Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 2, 3584 CS Utrecht, the Netherlands 3Department of Earth Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, 741246 Mohanpur, West Bengal, India 4Division of Geological and Planetary Science, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, California 91125, USA 5Institute for Geotechnical Engineering, ETH Zürich, Stefano-Franscini-Platz 3, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 6Laboratory of Ion Beam Physics, ETH Zürich, Otto-Stern-Weg 5, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 7Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre AMS Laboratory, Rankine Avenue, East Kilbride, G75 0QF Glasgow, Scotland 8Geology and Geophysics Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 86 Water Street, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Correspondence: Muhammed Ojoshogu Usman ([email protected]) Received: 12 January 2018 – Discussion started: 8 February 2018 Revised: 18 May 2018 – Accepted: 24 May 2018 – Published: 7 June 2018 Abstract. The modern-day Godavari River transports large sediment mineralogy, largely driven by provenance, plays an amounts of sediment (170 Tg per year) and terrestrial organic important role in the stabilization of OM during transport carbon (OCterr; 1.5 Tg per year) from peninsular India to the along the river axis, and in the preservation of OM exported Bay of Bengal. -

![DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN. [Dowr] ****************************************** 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6501/disaster-management-plan-dowr-1-1816501.webp)

DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN. [Dowr] ****************************************** 1

DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN. [DoWR] ****************************************** 1. Introduction The state Odisha is ranked as the 5th most flood prone state of the country after UP, Bihar, Assam and West Bengal with a flood prone area of 33400 km2. The south-west monsoon brings rains to the state from June to September every year. The state receives an average annual rainfall of 1500 mm and more than 80% of it occurs during monsoon period only. The coastal districts of the state are more vulnerable to frequent low pressure, cyclonic storms, depression and deep depression. The state has five major river basins namely Mahanadi, Brahmani, Baitarani, Subarnarekha and Rushikulya which cause high floods in their respective deltas. The rivers like Vamshadhara and Burhabalang also cause flash floods due to instant runoff from their hilly catchment. It is a fact that the three major river system Mahanadi, Brahmani and Baitarani forms a single delta during high flood and in most of the cases the flood water of these three systems blend together causing considerable flood havoc. Besides the state has 476.40 kms of coastline on the west of Bay of Bengal. The flood problem becomes more severe when the flood synchronies with high tides causing slow recede of flood. The silt deposited constantly by the waves in the delta area raises the flood level and the rivers often overflow their banks. The flood problem in the state generally aggravated due to some or all of the reasons as below: - Erratic monsoon, heavy monsoon rainfall accompanied by low pressures, depressions, deep depressions and cyclones. - Dam releases due to heavy inflows, thus causing massive outflows in the river. -

March-April 2003

Dams, Rivers & People UPDATE ON RELATED ISSUES SANDRP VOL 1-ISSUE 2-3 MARCH-APRIL 2003 INDEX About DRP 1 Let’s have feet on ground, Mr Prabhu (Himanshu Thakkar, SANDRP) 2 River Link News: How the Opposition is Mounting 5 Famine of Good deeds and ideas (Anupam Mishra) 7 Appeal by Scientists of West Bengal (Kalyan Rudra and Samar Bagchi) 8 Thoughts on Linking Rivers: Can We manage existing systems? (GK Bhat) 9 Bhakra: Reality behind legend (Shripad Dharmadhikary and Swathi Seshadri) 10 Bankrupt Math of WWF (Patrick McCully) 11 Pesticides in YOUR bottled water (Compiled by Bipin Chandra, SANDRP) 12 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- News from the Narmada Valley 14 Publications available at SANDRP 29 Hydro Projects 15 Water Privatisation 30 Dams in South Asia 16 QUOTES 32 Silted Reservoirs of Japan 18 Koshi Victims of Flood Protection 33 92 dams scrapped in Japan 19 Muhane River struggle in Bihar 34 HR Crisis at Three Gorges 20 “Death by Hunger is Murder” 35 Irrigation Scams 21 Punjab village for sale 36 Poor Performance in Bihar 22 Power Options 38 RIDF is flop 23 Small Hydro 39 Water a Human Right: UN 24 Uttaranchal Invites Private sector 40 Groundwater 25 Public washing of dirty linen 41 Rainwater Harvesting 26 Foreign Investors are going out 42 Plan to save Nagpur water bodies 27 YOUR RESPONSES 44 Toti Bachao Morcha in Punjab 28 ABOUT Dams, Rivers & People The DRP will be available both in electronic (text To clearly reflect the issues we are dealing with, we and word versions) and printed versions. The DRP have decided to change the name of our periodical are also available at www.narmada.org/sandrp and to Dams, Rivers & People. -

India Upper Indravati Irrigation Project Field Survey

India Upper Indravati Irrigation Project Field Survey: July 2003 1. Project Profile and Japan’s ODA Loan China New Delhi Nepal Bhutan Bangladesh Calcutta Myanmar India Bhubaneshwar Mumbai Project Site Site Map Indravati Main Canal 1.1 Background In India, expansion and improvement of irrigation facilities has been emphasized as a measure to alleviate repeatedly occurring drought damage, as a part of the country’s food self-sufficiency policy. Irrigation facilities are absolutely indispensable in low precipitation regions because the amount of rainfall in India is unpredictable and varies substantially by region, season, and year. Moreover even in heavy precipitation regions, irrigation facilities are extremely important for providing water for agricultural use during the summer season when demand for water is at its peak. The total land area under irrigation in India was scheduled to increase to approximately 57 million hectares by the conclusion of the sixth 5-year plan (March 1985) and to approximately 68 million hectares by the conclusion of the seventh plan (FY 1985- FY1989). The Orissa State Government launched the Upper Indravati Multipurpose Project in 1978 to promote the comprehensive development of the region, which tends to suffer from drought. The project was composed of three units, Unit I (dams and reservoirs), Unit II (irrigation), and Unit III (hydroelectric power). The purpose of this project was to construct a dam on the upper Indravati River, a branch of the Godavari River, discharge the water to the Mahanadi River basin, and produce 600 MW (four generators at 150 MW per generator) of hydroelectric power. In conjunction, the water used to generate the hydroelectric power would then be used for irrigation of approximately 109,000 ha. -

A Review of Methods of Hydrological Estimation at Ungauged Sites in India. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute

WORKING PAPER 130 A Review of Methods of Hydrological Estimation at Ungauged Sites in India Ramakar Jha and Vladimir Smakhtin Postal Address P O Box 2075 Colombo Sri Lanka Location 127, Sunil Mawatha Pelawatta Battaramulla Sri Lanka Telephone +94-11 2880000 Fax +94-11 2786854 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.iwmi.org SM International International Water Management IWMI isaFuture Harvest Center Water Management Institute supportedby the CGIAR ISBN: 978-92-9090-693-3 Institute Working Paper 130 A Review of Methods of Hydrological Estimation at Ungauged Sites in India Ramakar Jha and Vladimir Smakhtin International Water Management Institute IWMI receives its principal funding from 58 governments, private foundations and international and regional organizations known as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Support is also given by the Governments of Ghana, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The authors: Ramakar Jha is a Research Scientist at the National Institute of Hydrology (NIH), Roorkee, India. Vladimir Smakhtin is Principal Scientist in Hydrology and Water Resources at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, Sri Lanka. Jha, R.; Smakhtin, V. 2008. A review of methods of hydrological estimation at ungauged sites in India. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute. 24p. (IWMI Working Paper 130) / hydrology / models / river basins / runoff / flow / low flows/ flow duration curves/ estimation / flooding /unit hydrograph/ungauged basins/ India / ISBN 978-92-9090-693-3 Copyright © 2008, by IWMI. All rights reserved. Please direct inquiries and comments to: [email protected] ii Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................ v Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Estimating Low Flows and Duration Curves at Ungauged Sites .............................................. -

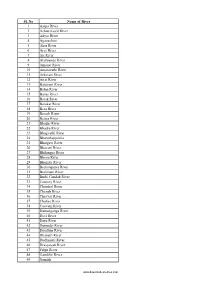

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90 -

Flood Forecasting and Warning Network Performance Appraisal Report 2013

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION FLOOD FORECAST MONITORING DIRECTORATE Uttarakhand Floods on the bank of River Mandakini in Rudraprayag June, 2013 FLOOD FORECASTING AND WARNING NETWORK PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL REPORT 2013 NEW DELHI – 110066 July 2014 Member (RM) Central Water Commission Sewa Bhawan, R. K. Puram New Delhi-110066 PREFACE Central Water Commission had started Flood Forecasting & Warning service in India in November 1958 by setting one forecasting station at Old Delhi Bridge, for the national capital, on the river Yamuna. Today, its network of Flood Forecasting and Warning Stations gradually extended covering almost all the major inter-state flood prone river basins throughout the country. It comprises of 175 Flood Forecasting Stations including 28 inflow forecast in 9 major river basins and 71 sub basins of the country. It covers 15 states besides NCT Delhi and UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli. The flood forecasting activities of the Commission are being performed every year from May to October through its 20 field divisions which issue flood forecasts and warnings to the civil authorities of the states as well as to other organizations of the central & state governments, as and when the river water level touches or is expected to cross the warning level at the flood forecasting stations. Inflow Forecasts are issued for 28 reservoir/dam/barrages. The forecasts are formulated whenever the inflow into the dam exceeds the threshold value fixed by the respective project authorities for reservoir regulation as well as flood moderation. The flood season 2013 witnessed unprecedented flood events at 3 stations in the rivers Alaknanda, Ganga and Yamuna in the country. -

Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter

CROCODILE SPECIALIST GROUP _____________________________________________________________________________________ NEWSLETTER VOLUME 21 No. 3 ! JULY 2002 – SEPTEMBER 2002 IUCN - World Conservation Union ! Species Survival Commission The CSG NEWSLETTER is produced and distributed by the Crocodile Specialist Group of the Species Survival CROCODILE Commission, IUCN – The World Conservation Union. CSG NEWSLETTER provides information on the conservation, status, news and current events concerning crocodilians, and on the activities of the SPECIALIST CSG. The NEWSLETTER is distributed to CSG members and, upon request, to other interested individuals and organizations. All subscribers are asked to contribute news and other materials. A GROUP voluntary contribution (suggested $40.00 US per year) is requested from subscribers to defray expenses of ____________________________ producing the NEWSLETTER. All communications should be addressed to: Dr. J. P. Ross, Executive Officer CSG, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA. Fax 1 352 392 9367, E- NEWSLETTER mail [email protected] ____________________________ VOLUME 21 Number 3 PATRONS JULY 2002 – SEPTEMBER 2002 We gratefully express our thanks to the following patrons who have donated to the CSG conservation program during 2002. IUCN−The World Conservation Union Species Survival Commission Big Bull Crocs! ($25,000 or more annually or in aggregate donations) ____________________________ Japan, JLIA − Japan Leather & Leather Goods Industries Association, CITES Promotion Committee & All Japan Reptile Skin and Prof. Harry Messel, Chairman Leather Association, Tokyo, Japan. IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group Mainland Holdings Ltd., Lae, Papua New School of Physics Guinea. University of Sydney Heng Long Leather Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore. Australia Reptilartenshutz, Offenbach am Main, Germany. D. & J. Lewkowicz, France Croco et Cie-Inter Reptile, Paris, France.