Detailed Species Accounts from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

“China’s Global Quest for Resources and Implications for the United States” January 26, 2012 Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Elizabeth Economy C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and Director, Asia Studies Council on Foreign Relations Introduction China’s quest for resources to fuel its continued rapid economic growth has brought thousands of Chinese enterprises and millions of Chinese workers to every corner of the world. Already China accounts for approximately one-fourth of world demand for zinc, iron and steel, lead, copper, and aluminum. It is also the world’s second largest importer of oil after the United States. And as hundreds of millions of Chinese continue to move from rural to urban areas, the need for energy and other commodities will only continue to increase. No resource, however, is more essential to continued Chinese economic growth than water. It is critical for meeting basic human needs, as well as demands for food and energy. As China’s leaders survey their water landscape, the view is not reassuring. More than 40 mid to large sized cities in northern China, such as Beijing and Tianjin, boast crisis- level water shortages.1 As a result, northern and western cities have been drawing down their groundwater reserves and causing subsidence, which now affects a 60 thousand kilometer area of the North China Plain. 2 According to the director of the Water Research Centre at Peking University Zheng Chunmiao, the water table under the North China Plain is falling at a rate of about a meter per year.3 -

Scope for Reallocation of River Waters for Agriculture in the Indus Basin Z

Scope for Reallocation of River Waters for Agriculture in the Indus Basin Z. Habib To cite this version: Z. Habib. Scope for Reallocation of River Waters for Agriculture in the Indus Basin. Environmental Sciences. Spécialité Sciences de l‘eau, ENGREF Paris, 2004. English. tel-02583835 HAL Id: tel-02583835 https://hal.inrae.fr/tel-02583835 Submitted on 14 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cemagref / d'Irstea ouverte archive : CemOA Recherches Coordonnées sur les Systèmes Irrigués RReecchheerrcchheess CCoooorrddoonnnnééeess ssuurr lleess SSyyssttèèmmeess IIrrrriigguuééss ECOLE NATIONALE DU GENIE RURAL, DES EAUX ET DES FORÊTS N° attribué par la bibliothèque /__/__/__/__/__/__/__/__/__/__/ THESE présentée par Zaigham Habib pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l'ENGREF en Spécialité: Sciences de l’eau Cemagref / Scope for Reallocation of River Waters for d'Irstea Agriculture in the Indus Basin ouverte archive à l'Ecole Nationale du Génie Rural, des Eaux et Forêts : Centre de Paris CemOA soutenue publiquement 23 septembre 2004 devant -

Pops in South Asia Status and Environmental Health Impacts

POPs in South Asia Status and environmental health impacts A survey of the available information of POPs in the South East Asian Region. The information is examined to reveal the nature and extent of the POPs problem. July 2004; Toxics Link Acknowledgements: The report entailed extensive research work involving data collection from various research institutes and organizations. We have been much assisted in our endeavor at data collection by scientists from Industrial Toxicological Research Institute (ITRC), National Institute of Occupational Heath (NIOH), National Environmental Engineering Re- search Institute (NEERI), NIO, Regional Research Laboratory (RRL) Trivandrum, Consumer Education Research Center (CERC), Institute for Toxicological Studies (INTOX), Bhaba Atomic Research Centre (BARC), Malaria Research Centre (MRC), Ministry of Environment and Forest (MOEF), Indian Council of Agriculture Research (ICAR), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Central Electricity Authority (CEA), Power Grid Corporation, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), Bose Institute, Centre for Study of Man and Environment (CSME), Centre for Science and environment (CSE), Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON), Wildlife Institute of India (WII), National Anti Malaria Program (NAMP), Educational Research Institute ERI (Pakistan), The Central Pulp and Paper Research Institute (CPPRI), Confederation of Indian Industries (CII), Delhi University, Jadavpur University, Kolkata University, Kalyani University, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay, Karachi University and Indian Agriculture Re- search Institute (IARI). We are also thankful to all the scientists who have spared their time, informally interacting with us and sharing their knowledge and experience. -

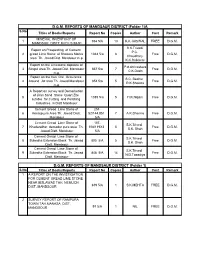

D.G.M. REPORTS of MANDSAUR DISTRICT (Folder 1)A D.G.M

D.G.M. REPORTS OF MANDSAUR DISTRICT (Folder 1)A S.No Titles of Books/Reports Report No Copies Author Cost Remark . MINERAL INVENTORY OF 1 934 5/A 13 K.K.JAISWAL FREE D.G.M. MANDSOR DISTT M.P.F.S 88-91 S.K.Trivedi Report on Prospecting of Cement P.C. 2 gread Lime Stone of Shakera Morka 1044 5/a 8 Free D.G.M. Choudhary area Th. Jawad Dist. Mandsaur m.p. K.K.Raikhere Report on the Limestone deposite of P.d.shrivastava 3 Singoli area Th. Jawad Dist. Mandsaur 867 5/a 7 Free D.G.M. C.K.Doshi m.p. Report on the Iron Ore Occurance S.C. Beohar 4 Around Jat area Th. Jawad Mandsaur 854 5/a 5 Free D.G.M. R.K.Sharma m.p. A Report on survey and Demarketion of Jiran Sand Stone Quart Zite 5 1089 5/a 5 H.K.Nigam Free D.G.M. sutable for Cutting and Polishing Industries in Distt Mandsour Cement Gread Lime Stone of 251- 6 Kesarpuyra Area Th. Jawad Distt. 52/144.851 7 A.K.Sharma Free D.G.M. Mandsour 5/A Cement Gread Lime Stone of 107- S.K.Trivedi 7 Khedarathor demodar pura area Th. 108/119X3 5 Free D.G.M. S.K. Shah Jawad Distt. Mandsour 5/A Cement Gread Lime Stone of S.K.Trivedi 8 Sukedha Extension Block Th. Jawad 805 5/A 5 Free D.G.M. S.K. Shah Distt. Mandsour Cement Gread Lime Stone of S.K.Trivedi 9 Sukedha Extension Block Th. -

Flood Management Strategy for Ganga Basin Through Storage

Flood Management Strategy for Ganga Basin through Storage by N. K. Mathur, N. N. Rai, P. N. Singh Central Water Commission Introduction The Ganga River basin covers the eleven States of India comprising Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, West Bengal, Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh and Delhi. The occurrence of floods in one part or the other in Ganga River basin is an annual feature during the monsoon period. About 24.2 million hectare flood prone area Present study has been carried out to understand the flood peak formation phenomenon in river Ganga and to estimate the flood storage requirements in the Ganga basin The annual flood peak data of river Ganga and its tributaries at different G&D sites of Central Water Commission has been utilised to identify the contribution of different rivers for flood peak formations in main stem of river Ganga. Drainage area map of river Ganga Important tributaries of River Ganga Southern tributaries Yamuna (347703 sq.km just before Sangam at Allahabad) Chambal (141948 sq.km), Betwa (43770 sq.km), Ken (28706 sq.km), Sind (27930 sq.km), Gambhir (25685 sq.km) Tauns (17523 sq.km) Sone (67330 sq.km) Northern Tributaries Ghaghra (132114 sq.km) Gandak (41554 sq.km) Kosi (92538 sq.km including Bagmati) Total drainage area at Farakka – 931000 sq.km Total drainage area at Patna - 725000 sq.km Total drainage area of Himalayan Ganga and Ramganga just before Sangam– 93989 sq.km River Slope between Patna and Farakka about 1:20,000 Rainfall patten in Ganga basin -

"Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 10 Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan Nadia Yousuf Bioresource Research Centre, Isalamabad, Pakistan Kainaat William Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan Madeeha Manzoor Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Balqees Khanum Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Yousuf, N., William, K., Manzoor, M., & Khanum, B. (2015). Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan, Journal of Bioresource Management, 2 (3). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.5102.0034 ISSN: 2309-3854 online This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal -

Flood Forecasting and Warning Networkperformanceapprmsal 2008

FLOOD FORECASTING AND WARNING NETWORKPERFORMANCEAPPRMSAL 2008 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION FLOOD FORECAST MONITORING DIRECTORATE NEW DELHI - 110066 Feb,2010 PREFACE Central Water Commission had made a small beginning in Flood Forecasting & Warning service in India in November 1958 with .one forecasting station at Delhi, the national capital, on the river Yamuna. Today, its network of Flood Forecasting and Warning Stations has gradually extended over the years and covers almost all the major inter-state flood prone river basins throughout the country. The network comprised of 175 Flood Forecasting Stations including 28 inflow forecast during the year 2008, in 9 major river basins and 71 sub basins of the country. It covered 15 states besides NCT Delhi and UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli. The flood forecasting activities of the Commission are being performed every year from May to October through its 21 field divisions which issue flood forecasts and warnings to the civil authorities of the states as well as to other organizations of the central & state governments, as and when the river water level touches or is expected to touch the warning level at the flood forecasting stations. The flood season 2008 witnessed unprecedented flood events in recent history. Both the river Subarnarekha at Rajghat and river Ghaghra at Ayodhya had once again recorded in 2008 a fresh "unprecedented Flood", for the second consecutive year after experiencing a similar event in 2007. In addition, "unprecedented Flood" was recorded on river Puthimari at N.H.Road crossing, river Devi, a distributory of river Mahanadi at Alipingal and Gharghra at Elgin Bridge. -

The Conservation Action Plan the Ganges River Dolphin

THE CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN FOR THE GANGES RIVER DOLPHIN 2010-2020 National Ganga River Basin Authority Ministry of Environment & Forests Government of India Prepared by R. K. Sinha, S. Behera and B. C. Choudhary 2 MINISTER’S FOREWORD I am pleased to introduce the Conservation Action Plan for the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica) in the Ganga river basin. The Gangetic Dolphin is one of the last three surviving river dolphin species and we have declared it India's National Aquatic Animal. Its conservation is crucial to the welfare of the Ganga river ecosystem. Just as the Tiger represents the health of the forest and the Snow Leopard represents the health of the mountainous regions, the presence of the Dolphin in a river system signals its good health and biodiversity. This Plan has several important features that will ensure the existence of healthy populations of the Gangetic dolphin in the Ganga river system. First, this action plan proposes a set of detailed surveys to assess the population of the dolphin and the threats it faces. Second, immediate actions for dolphin conservation, such as the creation of protected areas and the restoration of degraded ecosystems, are detailed. Third, community involvement and the mitigation of human-dolphin conflict are proposed as methods that will ensure the long-term survival of the dolphin in the rivers of India. This Action Plan will aid in their conservation and reduce the threats that the Ganges river dolphin faces today. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. R. K. Sinha , Dr. S. K. Behera and Dr. -

ABSTRACT LU, CHI. Natural and Human Impacts on Recent

ABSTRACT LU, CHI. Natural and Human Impacts on Recent Development of Yangtze River and Mekong River Deltas. (Under the direction of Dr. Paul Liu). The Yangtze River Delta is the largest delta in China and is also a highly populated delta where metropolitan cities such as Shanghai are located. The evolution of Yangtze River Delta will directly influence the economics and environment in this area. The sediment flux from Yangtze into the delta decreased during the past three decades and the operation of world’s largest hydropower project, Three Gorges Dam, made this situation much more severe. In the delta area, another large project called Deep Water Navigation Channel was also completed in recent years. Mekong River Delta is another major delta in Asia and also has a lot of dams in the river basin. To document the relationship between human impacts on the large river basin and coastal evolution, in this study, we used Jiuduan Island of Yangtze River Delta and two islands of Mekong River Delta as examples and utilized Landsat data to show how these island’s shoreline changed with the trend of decreased sediment discharge. In Mekong River Delta, the shoreline change agreed well with the sediment flux, eroding from 1989 to 1996 and prograding from 1996 to 2002. In Yangtze River Delta, shoreline kept growing before Three Gorges Dams was operating, eroded from 2003 to 2009 and then prograded again from 2011 to 2013. The main reason for the shoreline progradation from 2011 to 2013 was the impact of the Deep Water Navigation Channel project which totally changed the sediment transport process around Jiuduan Island. -

Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan

Socio#Hydrology of Channel Flows in Complex River Basins: Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Wescoat, James L., Jr. et al. "Socio-Hydrology of Channel Flows in Complex River Basins: Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan." Water Resources Research 54, 1 (January 2018): 464-479 © 2018 The Authors As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2017wr021486 Publisher American Geophysical Union (AGU) Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/122058 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ PUBLICATIONS Water Resources Research RESEARCH ARTICLE Socio-Hydrology of Channel Flows in Complex River Basins: 10.1002/2017WR021486 Rivers, Canals, and Distributaries in Punjab, Pakistan Special Section: James L. Wescoat Jr.1 , Afreen Siddiqi2 , and Abubakr Muhammad3 Socio-hydrology: Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of 1School of Architecture and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2Institute of Data, Coupled Human-Water Systems, and Society, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 3Lahore University of Management Systems Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan Key Points: This paper presents a socio-hydrologic analysis of channel flows in Punjab province of the Coupling historical geographic and Abstract statistical analysis makes an Indus River basin in Pakistan. The Indus has undergone profound transformations, from large-scale canal irri- important contribution to the theory gation in the mid-nineteenth century to partition and development of the international river basin in the and methods of socio-hydrology mid-twentieth century, systems modeling in the late-twentieth century, and new technologies for discharge Comparing channel flow entitlements with deliveries sheds measurement and data analytics in the early twenty-first century. -

B.A. 6Th Semester Unit IV Geography of Jammu and Kashmir

B.A. 6th Semester Unit IV Geography of Jammu and Kashmir Introduction The state of Jammu and Kashmir constitutes northern most extremity of India and is situated between 32o 17′ to 36o 58′ north latitude and 37o 26′ to 80o 30′ east longitude. It falls in the great northwestern complex of the Himalayan Ranges with marked relief variation, snow- capped summits, antecedent drainage, complex geological structure and rich temperate flora and fauna. The state is 640 km in length from north to south and 480 km from east to west. It consists of the territories of Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh and Gilgit and is divided among three Asian sovereign states of India, Pakistan and China. The total area of the State is 222,236 km2 comprising 6.93 per cent of the total area of the Indian territory including 78,114 km2 under the occupation of Pakistan and 42,685 km2 under China. The cultural landscape of the state represents a zone of convergence and diffusion of mainly three religio-cultural realms namely Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists. The population of Hindus is predominant in Jammu division, Muslims are in majority in Kashmir division while Buddhists are in majority in Ladakh division. Jammu is the winter capital while Srinagar is the summer capital of the state for a period of six months each. The state constitutes 6.76 percent share of India's total geographical area and 41.83 per cent share of Indian Himalayan Region (Nandy, et al. 2001). It ranks 6th in area and 17th in population among states and union territories of India while it is the most populated state of Indian Himalayan Region constituting 25.33 per cent of its total population. -

MMIW" 1. (8Iiira)

..nth Ser... , Vol. ru, No. 11 ...,. July 1., 200t , MMIW" 1. (8IIIra) LOK SABHA DEBATES (Engllah Version) Second Seulon (FourtMnth Lok Sabha) (;-. r r ' ':1" (Vol. III Nos. 11 to 20) .. contains il'- r .. .Ig A g r ~/1'~.~.~~: LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price : Rs. 50.00 EDITORIAL BOARD G.C. MalhotrII Secretary-General Lok Sabha Anand B. Kulkllrnl Joint Secretary Sharda Prued Principal Chief Editor telran Sahnl Chief Editor Parmnh Kumar Sharma Senior Editor AJIt Singh Yed8v Editor (ORIOINAL ENOUSH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGUSH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE.TREATED AS AUTHORITA11VE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION THEREOF) CONTENTS ,.. (Fourteenth Serles. Vol. III. Second Session. 200411926 (Saka) No. 11. Monday. July 19. 2OO4IAudha, 28. 1121 CSU-) Sua.lECT OBITUARY REFERENCE ...... ...... .......... .... ..... ............................................ .......................... .................................... 1·2 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question No. 182-201 ................................................................. ................ ................... ...................... 2-36 Unstarred Question No. 1535-1735 .................... ..... ........ ........ ...... ........ ......... ................ ................. ........ ......... 36-364 ANNEXURE I Member-wise Index to Starred List of Ouestions ...... ............ .......... .... .......... ........................................ ........... 365 Member-wise Index to Unstarred Ust of Questions ........................................................................................