Goluboff on Naroditskaya, 'Song from the Land of Fire: Continuity and Change in Azerbaijanian Mugham'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Conflicts in the Caucasus: History, Present, and Prospects for Resolution Special Issue Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 FOUNDEDTHE CAUCASUS AND& GLOBALIZATION PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 510 32 52 E-mail: [email protected] (IMANOV) Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 6 IssueMembers 2 2012 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. -

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 8 Issue 3-4 2014 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION FOUNDED AND PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 – 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 561 70 54 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 – 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 – 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 – 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 598 27 53 (Ext. 25) (IMANOV) E-mail: [email protected] Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 561 70 54 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 8 IssueMembers 3-4 2014 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. (History), Professor, Corresponding member of the Georgian National Academy of ALEKSIDZE Sciences, head of the scientific department of the Korneli Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts (Georgia) Mustafa AYDIN Rector of Kadir Has University (Turkey) Irina BABICH D.Sc. -

The National Emblem

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y NATIONAL EMBLEM Contents National Emblem ........................................................................................................................... 2 The emblems of provinces ............................................................................................................ 3 The emblems of Azerbaijani cities and governorates in period of tsarist Russia ................... 4 Caspian oblast .............................................................................................................................. 4 Baku Governorate. ....................................................................................................................... 5 Elisabethpol (Ganja) Governorate ............................................................................................... 6 Irevan (Erivan) Governorate ....................................................................................................... 7 The emblems of the cities .............................................................................................................. 8 Baku .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Ganja ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Shusha ....................................................................................................................................... -

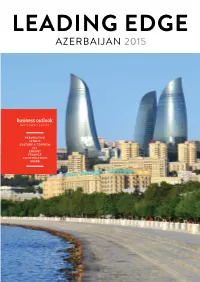

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

Arrival in Baku Itinerary for Azerbaijan, Georgia

Expat Explore - Version: Thu Sep 23 2021 16:18:54 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/15 Itinerary for Azerbaijan, Georgia & Armenia • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Hotel in Baku, Hotel in Yerevan, Please contact us Please contact us from 14:00 hrs 10:00 hrs DAY 1: Arrival in Baku Start in Baku, the largest city on the Caspian Sea and capital of Azerbaijan. Today you have time to settle in and explore at leisure. Think of the city as a combination of Paris and Dubai, a place that offers both history and contemporary culture, and an intriguing blend of east meets west. The heart of the city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, surrounded by a fortified wall and pleasant pedestrianised boulevards that offer fantastic shopping opportunities. Attractions include the local Carpet Museum and the National Museum of History and Azerbaijan. Experiences Expat Explore - Version: Thu Sep 23 2021 16:18:54 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/15 Arrival. Join up with the tour at our starting hotel in Baku. If you arrive early you’ll have free time to explore the city. The waterfront is a great place to stroll this evening, with a cooling sea breeze and plenty of entertainment options and restaurants. Included Meals Accommodation Breakfast: Lunch: Dinner: Hotel Royal Garden DAY 2: Baku - Gobustan National Park - Mud Volcano Safari - Baku Old City Tour After breakfast, dive straight into exploring the history of Azerbaijan! Head south from Baku to Gobustan National Park. This archaeological reserve is home to mud volcanoes and over 600,000 ancient rock engravings and paintings. -

Persia: the Land of the Imams

PERSIA THE LAND OF THE IMAMS A NARRATIVE OF TRAVEL AND RESIDENCE 1871-1885 BY JAMES BASSETT MISSIONARY OF THE PRESBYTERIAN BOARD BLACKIE & SON 49 AND 50 OLD BAILEY GLASGOW, EDINBURGH, AND DUBLIN 1887 1916 PERSIA! LAND OF THE IMAMS. PREFACE. The name Persia is not known to the people inhabiting the country so called by Europeans. Persians call their land, Eran. This name is evidently from Arya or Ariya, whence we have the form Iranian and Iran. The term Persia comes to us from the Greeks, who derived it from the term Fars or Pars, the designation, at this time, of a province of Eran. The country called Persia has been designated by several terms which were emblematic only; as, "The Land of Fire," to denote the worship of fire ; " The Land of the Sun," expressive of the brilliancy of the sunlight, and possibly in allusion to the reverence paid to the sun ; " The Land of the Lion and the Sun," since the flag of Persia has the device of the sun in the form of a human face peering above the back of a lion. The device is the symbol of intelligence, light, power and justice. Per sians frequently call their country, " Memlakate Asna Asherain," or the Kingdom of the Twelve, meaning by this the twelve Imams of the house of Ale. vi PREFACE. The traveller in that land will find in all the people the evidence of the power of the religious system bear ing this name. The people of all classes invoke the names of the Imams. -

Azerbaijan in Transition

Istituto Affari Internazionali IAI WORKING PAPERS 12 | 20 – July 2012 ISSN 2280-4331 Azerbaijan in Transition Jens Hölscher Abstract Azerbaijan has been the fastest growing economy of the world and it increasingly attracts the interest of foreign investors. This paper analyses the Azerbaijani economy in transition from communism to capitalism over the past decade with a focus on investment climate. Facts and figures of the apparent economic miracle are presented and a number of political obstacles considered. Azerbaijan’s transition towards a market economy has not gone very far and it is mainly slowed down by low levels of trust and high levels of corruption. There are also human rights issues and freedom or press is limited. Unless and until Azerbaijan deals with these problems, shadows will continue to loom over its economic miracle. Keywords: Azerbaijan economy / Economic transition / Foreign investments / Business climate / Corruption / Human rights © 2012 IAI ISBN 978-88-98042-57-9 IAI Working Papers 1220 Azerbaijan in Transition Azerbaijan in Transition by Jens Hölscher Introduction Azerbaijan has an ancient history, sometimes referred to as “the land of fire”. In Greek mythology, Prometheus was chained to the Caucasus Mountains, as he stole the fire from the gods and brought it to human beings. Indeed, an abundance of gas and oil resources give rise to open fires in Azerbaijan, there where mankind struggled to discover fire elsewhere for a long time. These energy riches are the core of the economy of Azerbaijan. The purpose of this paper is to analyse the Azerbaijani economy in transition from communism to capitalism. -

Iran the US and Azerbaijan

Wednesday, December 5, 2012 Iran, the U.S. and Azerbaijan: the Land of Fire By Stanley A. Weiss LONDON -- In December 1991, shortly after the fall of the Council. Soviet Union, United States Secretary of State James Baker gave a speech at Princeton University on the relationship between the One of the most surprising aspects of Azerbaijan -- which is 85 U.S. and the "Newly Independent States" of the former USSR. percent Shi'ite Muslim -- is its close alliance with Israel. Prime In his remarks, Baker took aim at a curious target: the tiny Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited during his first term in Republic of Azerbaijan -- about the size of the state of Maine -- office, in 1997, and the partnership has only deepened since -- which Baker described as undeserving of American recognition particularly as long-time Israeli ally Turkey has turned its back until it accepted a long list of conditions the U.S. had required of on Tel Aviv. Israel is now the second-largest importer of few other nations. Soviet watchers saw it as the work of the U.S. Azerbaijani oil, and with the recent signing of a $1.6 billion lobby of Azerbaijan's neighbor and sworn enemy, Armenia, to arms agreement, the military relationship between the two blacklist the ancient nation in the Caucuses region on the countries has raised eyebrows. Earlier this year, Iran accused Caspian Sea. Azerbaijan of supporting anti-Iranian activity by Israel's Mossad, while Azerbaijan charged 22 suspects in an Iranian plot But it proved to be the shortest blacklist in history. -

The Land of Fire - Azerbaijan

Beat: Travel THE LAND OF FIRE - AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN Baku, 14.02.2016, 20:08 Time USPA NEWS - Today, we would like to talk about a miraculous country of Azerbaijan with its unlimited natural resources, centuries- old culture, history and ancient people, whose lifestyle presents a unique and harmonious combination of the traditions and ceremonies of different cultures and civilizations. Azerbaijan is a geographical name. On the one hand this name is linked with the population, which lived in this region for thousand of years before our era, and who were mostly fire-worshippers. Local population considered that fire was their God and so they worshipped the fire. "Azer" means fire. The Turkic name "Azer" was used for this territory for a long time. The word "Azer" consists of two parts - "az" and "er". In Turkic languages, "az" means a good intention and a fate of success. Thus, the word "Azer" means "a brave man", "a brave boy", "the fire keeper". The word "Azerbaijan" originates from the name of an ancient Turkish tribe, who resided in those territories. Azerbaijan is one of the most ancient sites of humankind. The humankind was present here at every stage of their historical development. There were living settlements in Azerbaijan even at the earliest stages of humankind. Azerbaijan made its own contribution into the establishment of the current culture and civilization, progress and dialectics. The time kept a range of ancient archeological and architectural monuments for us. The ancient headstones, manuscripts and models of carpets, preserved to the present times from the ancient ages, can provide much information to those who can and want to read them. -

Country Report 2011

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty ティ s け Thi uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnAZERBAIJAN COUNTRY REPORT mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert 9/28/2011 yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopaEMIN NAZAROV sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjkl zxcvbnmqwertyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjkl zxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq Disclaimer This report was compiled by an ADRC visiting researcher (VR) from ADRC member countries. The views expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADRC. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on the maps in the report also do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the ADRC. 2 Table of Contents 1.COUNTRY PROFILE ................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 LANDSCAPE AND TOPOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 CLIMATE ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Melanie Krebs from Cosmopolitan

Melanie Krebs From cosmopolitan Baku to tolerant Azerbaijan – Branding “The Land of Fire” Abstract Over the last years the Azerbaijani government made strong efforts to brand the country as a symbol of a century-long coexistence of different ethnicities and religions, while at the same time neglecting or even de- stroying the traces of what is remembered by elderly inhabitants as the “cosmopolitan” Baku of the 1960’s and 1970’s. The paper analyzes how the inhabitants of Baku are going “behind the branding strategy” as the branding expert Anholt claims for good branding (Anholt 2003) and at which points they refuse the new image of their city, which neglects parts of their own biography. The paper is based on print media, websites and videos issued by the Azerbaijani government and on interviews with Bakuvians between the ages of 20 and 70 from different social and eth- nic backgrounds. Keywords: Azerbaijan, Baku, post-soviet city, nation branding, urban identity From cosmopolitan Baku to tolerant Azerbaijan – Branding “The Land of Fire” Holding the Eurovision Song Contest 2012 in Baku was just the high- light of many efforts made over the last decade by the Azerbaijani govern- ment to present the country, and especially the capital Baku, to a global audi- ence. Place branding – either for the capital or the whole country – had be- come very important for Azerbaijan and the impact of these branding efforts on the identity of the population will be the primary focus of this paper. The aim is to brand Azerbaijan as a modern and well-off country with a multi- cultural history and a hospitable and tolerant population in order to attract tourists and foreign investors, as well as create an international environment of sympathy for a country that lost parts of its territory to neighbouring Ar- menia after the war over Karabakh in 1994. -

National Urban Assessment 2017

Strengthening Functional Urban Regions in Azerbaijan National Urban Assessment This publication helps guide investment planning and financing across key urban infrastructure sectors of Azerbaijan to improve the performance of cities—with a focus on economy, equity, and environment. The National Urban Assessment for Azerbaijan is among a series prepared by the Asian Development Bank for selected developing countries under its Urban Operational Plan 2012–2020. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty. Established in 1966, it is owned by 67 members— 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. STRENGTHENING FUNCTIONAL URBAN REGIONS IN AZERBAIJAN National Urban Assessment 2017 DECEMBER 2018 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org STRENGTHENING FUNCTIONAL URBAN REGIONS IN AZERBAIJAN National Urban Assessment 2017 DECEMBER 2018 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2018 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2018. ISBN 978-92-9261-378-5 (print), 978-92-9261-379-2 (electronic) Publication Stock No. TCS179176 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS179176 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent.