Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Anglican Books

Our current stock of Anglican books. Last updated 27/04/2017 Ang11236) ; WHAT WAS THE OXFORD MOVEMENT? (OUTSTANDING CHRISTIAN THINKERS) £3.00 PUBLISHED BY (2002); CONTINNUUM; 2002; xii + 146pp; Paperback. slight wear only.() Ang12200) A Priest; OUR PRIESTS AND THEIR TITHES; Kegan Paul; 1888; xii+221 +[48]pp; £15.00 Hardback, boards slightly dampstained. Owner's inscription to title. Sl. Edge foxing.() Ang12248) A. B. Wildered Parishioner; THE RITUALIST'S PROGRESS; A SKETCH OF THE REFORMS £35.00 AND MINISTRATIONS OF OUR NEW VICAR THE REV. SEPTIMIUS ALBAN, MEMBER OF THE E.C.U., VICAR OF ST. ALICIA, SLOPERTOWN.; Samuel Tinsley; 1876; [6] + 103pp; Bound in shaken green decorative cloth. Endpapers inscribed . Text, cracks between gathers, a little light foxing. Anonymous, a satirical poem.() Ang12270) Addleshaw, G.W.O.; THE HIGH CHURCH TRADITION: A STUDY IN THE LITURGICAL £5.00 THOUGHT OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.; Faber and Faber; 1941; 204pp; 1st ed. Hardback, no dustjacket. Slight edge foxing otherwise clean and crisp.() Ang12213) Anon.; TALES OF KIRKBECK; OR THE PARISH IN THE FELLS. SECOND EDITION.; W. J. £3.00 Cleaver; 1848; [2] + 210 + 6pp; Original blue cloth, slight rubbing. Owner's inscription on the pastedown. A few fingermarks in places.() Ang12295) ANSON PETER F.; THE CALL OF THE DESERT: THE SOLITARY LIFE IN THE CHRISTIAN £7.00 CHURCH; S.P.C.K.; 1964; xx +278pp; Cloth boards foxing, front hinge weak. Ex. Lib. With usual stamps and markings. The text has some light foxing, otherwise clean and crisp.() Ang12232) Anson, Peter F.; THE BENEDICTINES OF CALDEY: THE STORY OF THE ANGLICAN £8.00 BENEDICTINES OF CALDEY AND THEIR SUBMISSION TO THE CATHOLIC CHURCH.; CATHOLIC BOOK CLUB; 194; xxx + 205pp; Hardback, slightly shaken, a little grubby, library mark to spine. -

The Bishop of Rochester, the Rt Rev James Langstaff, Has Presided at a Ceremony to Dedicate the Newly Opened Bishop Chavasse Church of England Primary School

The Bishop of Rochester, the Rt Rev James Langstaff, has presided at a ceremony to dedicate the newly opened Bishop Chavasse Church of England Primary School. The Bishop was welcomed by Headteacher Donna Weeks and reception pupils to a grand opening ceremony on Friday 1st December. Based on land next to the new Somerhill Green development, Bishop Chavasse Church of England Primary School opened its doors in September to its first two classes of reception children. The opening of this traditionally run primary school marks the return of Church of England education to Tonbridge. Until recently, parents who wanted a Church of England education had to travel outside of the town to the nearest church school in Tunbridge Wells. The new school, which has been made possible with money from central government, adds new primary places and significant capacity to Tonbridge and the families it serves. Tom Tugendhat MP for Tonbridge and Malling, who marked the event by cutting the ribbon and officially opening the school, said “I am delighted to have had the privilege of opening Bishop Chavasse Primary School today. This is already a fantastic school adding to the range serving the needs of our community here, in Tonbridge. I’m proud to have played a small part in making today a reality. I’m pleased that we can celebrate all the hard work that has gone into this school today and I wish everyone involved best wishes for the future.” Bishop Chavasse Church of England School is part of the Tenax Schools Trust that is led by the highly acclaimed Bennett Memorial Diocesan School in Tunbridge Wells. -

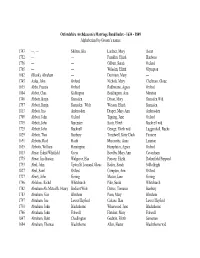

Alphabetized by Groom's Names

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Alphabetized by Groom’s names 1743 ---, --- Shilton, Bks Lardner, Mary Ascot 1752 --- --- Franklin, Elizth Hanboro 1756 --- --- Gilbert, Sarah Oxford 1765 --- --- Wilsden, Elizth Glympton 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1745 Aales, John Oxford Nichols, Mary Cheltnam, Glouc 1635 Abba, Francis Oxford Radbourne, Agnes Oxford 1804 Abbot, Chas Kidlington Boddington, Ann Marston 1746 Abbott, Benjn Ramsden Dixon, Mary Ramsden Wid 1757 Abbott, Benjn Ramsden Widr Weston, Elizth Ramsden 1813 Abbott, Jno Ambrosden Draper, Mary Ann Ambrosden 1709 Abbott, John Oxford Tipping, Jane Oxford 1719 Abbott, John Burcester Scott, Elizth Bucknell wid 1725 Abbott, John Bucknell George, Elizth wid Luggershall, Bucks 1829 Abbott, Thos Banbury Treadwell, Kitty Clark Finmere 1691 Abbotts, Ricd Heath Marcombe, Anne Launton 1635 Abbotts, William Hensington Humphries, Agnes Oxford 1813 Abear, Edmd Whitfield Greys Bowlby, Mary Ann Caversham 1775 Abear, Jno Burton Walgrove, Bks Piercey, Elizth Rotherfield Peppard 1793 Abel, John Upton St Leonard, Glouc Bailey, Sarah St Rollright 1827 Abel, Saml Oxford Compton, Ann Oxford 1727 Abery, John Goring Mason, Jane Goring 1796 Ablolom, Richd Whitchurch Pike, Sarah Whitchurch 1742 Abraham Als Metcalfe, Henry Bodicot Widr Dawes, Tomasin Banbury 1783 Abraham, Geo Bloxham Penn, Mary Bloxham 1797 Abraham, Jno Lower Heyford Calcote, Han Lower Heyford 1730 Abraham, John Blackthorne Whorwood, Jane Blackthorne 1766 Abraham, John Fritwell Fletcher, Mary Fritwell 1847 -

Xk Roll the Sons and Daughters of the Anglican Church Clergy

kfi’ XK R O L L the son s an d d au g hters o f the A ng lican C hu rch C lerg y throu g hou t the w orld an d o f t h e Nav al an d M ilitary C h ap lains o f the sam e w h o g av e the ir liv es in the G re at War 1914- 1918 Q ua: reg io le rrw n os t ri n o n ple n a lo baris ' With th e mo m th se A n e l aces smile o g f , Wh i h I h ave lo v ed l s i ce and lost awh ile c ong n . , t r i r Requiem e e n am do na e is Dom n e e t lax pe pet ua luceat eis . PR INTED IN G REAT B RITA I N FOR TH E E NGLIS H CR A FTS ME L S OCIETY TD M O U TA L . N N , . 1 A KE S I GTO PLA CE W 8 , N N N , . PREFA C E k e R e b u t I have ta en extreme care to compil this oll as ac curately as possibl , it is al m ost t d m d ke d inevitable that here shoul be o issions an that mista s shoul have crept in . W d c d u e ith regar to the former , if su h shoul unfort nately prov to be the case after this k d can d d o d boo is publishe , all I o is t o issue a secon v lume or an appen ix to this ' d t h e d can d with regar to secon , all I o is to apologise , not for want of care , but for inac curate information . -

Annex 8 – Academy Trusts Consolidated Into SARA 2018/19 This Annex Lists All Ats Consolidated Into SARA 2018/19, with Their Constituent Academies

Annex 8 – Academy Trusts consolidated into SARA 2018/19 This annex lists all ATs consolidated into SARA 2018/19, with their constituent Academies. * These Academies transferred into the AT from another AT during the year. ** Newly opened or converted to academy status during 2018/19. ^ These Academies transferred out of the AT into another AT during the year. + Closed during the year to 31 August 2019. ++ Closed prior to 31 August 2018. +++ ATs where the Academies had all transferred out over the course of 2018/19. # City Technology colleges (CTC) are included in the SARA consolidation, but do not appear in Annex 1 – Sector Development Data. Further details can be found at www.companieshouse.gov.uk by searching on the company number. -

The Case of Dunlavin, County Wicklow 1600 -1910

The establishment and evolution of an Irish village: the case of Dunlavin, county Wicklow 1600 -1910. Vol. 2 of 2 Chris Lawlor M.A., H.D.E. Thesis for the degree of PhD Department of History, St. Patrick’s College Drumcondra, A college of Dublin City University Head of department: Professor James Kelly Supervisor of research: Professor James Kelly May 2010 CHAPTER FIVE. DISASTER AND READJUSTMENT: DUNLAVIN, 1845-1901. Introduction. The Great Famine killed off all attempts to restore paternalistic landlordism, with its associated levels o f deference from the tenantry, which the Tynte family tried to restore in the early nineteenth century. There is a perception that county Wicklow was not badly affected by the Famine. 1 However, this chapter demonstrates that the Dunlavin region experienced acute levels of distress. Population losses in the area were significant, with a quarter of the village population, and a third o f the population o f the region no longer resident in the aftermath o f the disaster. Post-Famine Dunlavin emerged scarred and demographically frail. The lack o f employment opportunities and, the effects o f impartible inheritance o f land meant that emigration remained the only option for many young people in the Dunlavin region. Long-term demographic decline, attested to economic stagnation, but strong farming families consolidated their landholding position and provided the local economy with the means to stage a gradual recovery in the post-Famine era. Despite this, Dunlavin failed to grow in any respect during this time; no improvements were made to village furniture, and no new houses were erected. -

Trinity College Oxford Report 2010–11 0000 Cover.Qxp:S4493 Cover 20/12/2011 11:23 Page 2

0000_cover.qxp:S4493_cover 20/12/2011 11:23 Page 1 Trinity College Oxford Report 2010–11 0000_cover.qxp:S4493_cover 20/12/2011 11:23 Page 2 ©2010 Gillman & Soame 10017_text.qxp:Layout 1 20/12/2011 14:14 Page 1 Trinity College Oxford | Report 2010-11 | 1 CONTENTS THE TRINITY COMMUNITY.....................2 Margaret Malpas...........................................................................56 President’s Report...........................................................................2 Nigel Timms .................................................................................57 The Governing Body, Fellowship and Lecturers............................4 Members of College ....................................................................57 News of the Governing Body .........................................................7 JUNIOR MEMBERS ................................78 Members of Staff ..........................................................................12 JCR Report ...................................................................................78 Staff News ....................................................................................14 MCR Report .................................................................................79 New Undergraduates ....................................................................16 Clubs and Societies.......................................................................80 New Postgraduate Students ..........................................................18 Blues .............................................................................................88 -

HISTORY of the CHOIR of ROCHESTER CATHEDRAL James Strike: Editor

ROCHESTER CATHEDRAL OLD CHORISTERS’ ASSOCIATION HISTORY OF THE CHOIR OF ROCHESTER CATHEDRAL James Strike: editor. Chorister 1950-52. RCOCA Archivist. 604 Rochester Cathedral was founded in 604 when Archbishop Augustus ordained Justus as Bishop of Rochester. This first church was a simple stone building, the outline of which can be seen marked out on the paving at the west end of the present Cathedral. The earliest record of singing in the Cathedral is attributed to The Venerable Bede; monk, scholar and historian, who cites, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, Book IV : ‘When Archbishop Theodore of Tarsus arrived in England in 664, sacred music was only known in Kent. And when Putta was consecrated Bishop of Rochester in 669, he was extraordinarily skilful in the Roman style of music which he had learned from the disciples of the Holy Pope Gregory’. Rev. R. Johnstone, Rochester Cathedral Choir School. p.2. 1077 In 1077, Gundulf became Bishop of Rochester in 1077. He was a skilful builder, being favoured by the king, William I, for the construction of the White Tower at the Tower of London. During his thirty years as Bishop of Rochester he re-built the Cathedral and built the great Gundulf Tower by the North Transept. (used now for the Choir Practice Room and Music Library ) Palmer, The Cathedral Church of Rochester, p.121. 1082 In 1082 Bishop Gundulf founded the Benedictine Priory dedicated to St Andrew. At his death there were sixty monks. A.F.Leach, Medieval Schools. There seems little doubt that the Monks of the Priory had ‘Song-boys’ or ‘Cloister-boys’. -

ISSUE 2440 | Antiquestradegazette.Com | 2 May 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2440 | antiquestradegazette.com | 2 May 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Calendar begins revival via the virtual rostrum After a month’s hiatus, remotely. Some firms will also that Christie’s have run for a for June 3-4), with more than remote means, Fisher said the a number of top-tier be using timed online auctions. number of years, we felt this 700 lots, and an Oxford two- firm is not physically receiving regional auction houses are Mallams, one of many UK was the format that we should day of Jewellery, Watches, any new consignments. returning to the rostrum to regional firms that temporarily adopt,” said director Robin Silver & Objets de vertu sale “Travelling to a saleroom conduct ‘live online’ sales. closed their doors on March Fisher. on June 17-18. does not qualify as an essential In accordance with social- 23, has taken the decision to “Vendors have been very The merchandise offered journey and using couriers distancing rules, these will begin selling remotely in early positive and understanding.” was consigned pre-lockdown presents unnecessary risk. We typically be held by an June via live online only The revised calendar will before the saleroom closed and have decided to wait until the auctioneer alone in the auctions. -

Diocesan Schools' Overseas Links

School leader awarded CBE ochesterLink Education / July/August 2017 see page 3 Diocesan Schools’ Overseas links By Richard Tyson By Emma Honey & Cerys Siney By Leah Myles, Assistant Director of Sixth Form ince 2009, there have been five visits by rinity School have been visiting Mpwapwa for five and trip facilitator. SBennett Memorial students and two professional Tyears and recently celebrated a partnership with n 7 July 2017, 11 students from Bishop Justus development visits by teachers to Mwanakianga Queen Esther’s Secondary School for Girls. So far, 22 OSecondary School, Bromley will touch down secondary school, Mpwapwa, with a sixth visit planned students have taken part, with 12 already planning for in Kilimanjaro for a two-week ‘once in a lifetime’ for this July. our visit in 2018. Our mission is central to our School’s experience. This is the third year that students have core Christian value of compassion. The mission is a had the opportunity to visit the districts of Kondoa and Our students are able to offer those at Mwanakianga life-changing experience for all who attend, deepening Chemba where they will experience life beyond the lots of help with their English, maths and science in their own faith and spirituality. tourist trails of Kilimanjaro. As well as continuing to particular. The students play sport and hold formal help build a brand new school in Chemba, students debates together. They travel for a day trip to Our mission is aimed at enriching and supporting will be sharing skills and knowledge with the children. Tanzania’s capital city, Dodoma, together. -

CORRESPONDENCE, Length, and Never Graduated, I Have Used This Expedient So- That I May Know Exactly Where the Point Is ;And I Never, Except-In Certain URINARY FEVER

Dee. 29, 1888.] THB BRITJS.S ?DACJJRNAL 1319 It is respecting the first or "transient" form, that I am reported as saying, "it occurs in persons wh6 have not the most healthy ASSOCIATION. INTELLIGENCE urinary organs." The word " not." isthe error;' the exact reverse is that' which- I desired to express. - This' transient attack may; aud COUNCIL. commonly does, happen in persons who have hio sign whatever of NOTICE OF QUARTERLY MEETINGS FOR 1884: renal disease, or of inadequate excreting power. It is thus unlike ELECTION OF MEMBERS. to the second or - recurring" formh, which is associated, in many MEETINGS of the Council will be held on Wednesday, January 16th, cases, with some affection of the kidney, but one which is--not April 9th, July 9th, and October 15th, 1884. Gentlemen desirous of 'necessarily severe. On' the other hand -the recurring attacks may becoming members of the Association must send in their forms of prove to be the signs of a septicemic infection, or a«prelude -to .uremic application for election to the General Secretary not later than poisoning. It is unlike also to the third or " o6ntinuous " form, in twenty-onedaysbeforeeach meeting, viz., March 20th, June 20th, and which the renal organs are mostly considerably diseased. September 25th, 1884, in accordance with the regulation for the The "transient" form arises at any age after puberty, -often, election of members passed at the meeting of theCommittee of probably, as the result of absorption of a minute quantity of urine Council of October 12th, 1881. after a very slight injury to the urethra.