An Exploration of ICU Nurses Experiences of Post Mortem Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Care After Death (Replaces Last Offices) Policy and Procedure

Care after Death (replaces Last Offices) Policy and Procedure Document No D&O - 00082 Version No 1.0 Approved by Policy Governance Group Date Approved 13.02.19 Ratified by End of Life Committee Date Ratified 15.05.19 Date implemented ( made live for use) 16.05.19 Next Review Date 15.05.22 Status LIVE Target Audience- who does the document apply to and who Nursing and Health Care should be using it. - The target audience has the Assistant Employees, responsibility to ensure their compliance with this document Agency/Bank/Locum by: workers. Serco Group Ensuring any training required is attended and kept up PLC Porting Staff, to date. Chaplaincy, Mortuary and Ensuring any competencies required are maintained. Bereavement Service Co-operating with the development and implementation employees, Clinical of policies as part of their normal duties and Management. responsibilities. Special Cases Paediatric Cases. This policy does not cover care after death for paediatric patients. Ebola Cases. Handling of deaths resulting from Ebola are covered separately in the Management & Control of Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers Policy (Ref 15). Appendix 12: Care after death. Influenza Cases. Deaths resulting from Influenza are covered in the Influenza (including Pandemic influenza) Policy (Ref 14). Tuberculosis Cases. Deaths resulting from tuberculosis are covered in the Management and Control of Pulmonary Tuberculosis Policy (Ref 13). Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease (CJD) Cases. Deaths resulting from CJD are covered in the Infection Prevention and Control of CJD/vCJD and other Human Prion Diseases Policy (Ref 12). Viewing of the deceased – refer to the Mortuary and Bereavement Services Viewing Policy (Ref 7). -

Harmonized Curriculum for General Nursing Programme for Anglophone Countries of the Ecowas Region

1 HARMONIZED CURRICULUM FOR GENERAL NURSING PROGRAMME FOR ANGLOPHONE COUNTRIES OF THE ECOWAS REGION WEST AFRICAN COLLEGE OF NURSING HARMONIZED CURRICULUM FOR GENERAL NURSING PROGRAMME FOR ANGLOPHONE COUNTRIES OF THE ECOWAS REGION MARCH 2012 2 HARMONIZED CURRICULUM FOR GENERAL NURSING PROGRAMME FOR ANGLOPHONE COUNTRIES OF THE ECOWAS REGION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Table of contents Copyright Brief on West African College of Nursing(WACN) Brief on West African Health Organization(WAHO) Introduction Philosophy Outcome Objectives Competencies (Job Description for Registered Nurse) The Programmes Table of courses General Nursing courses Courses for 1st year 1st semester Human Anatomy and Physiology I Fundamentals of Nursing I Nursing Ethics & Professional Adjustments Use of English / Communications Skills Primary Health Care Nursing I Applied Basic Sciences (Physics, Chemistry) Behavioural Sciences I Introduction to French Language Courses for 1st year 2nd semester Human Anatomy and Physiology II Fundamentals of Nursing II Behavioural Sciences II Family/Reproductive Health I Introduction to traditional and Alternative Medicine Introduction to Information Communication Technology (ICT) First Aid and Bandaging Nutrition and Dietetics Microbiology Courses for 2nd year 1st semester Medical Nursing I Surgical Nursing I Pharmacology / Therapeutics I Primary Health Care Nursing II Pediatric Nursing I Family / Reproductive Health II 3 HARMONIZED CURRICULUM FOR GENERAL NURSING PROGRAMME FOR ANGLOPHONE COUNTRIES OF THE ECOWAS REGION Courses for 2nd year -

Religious and Cultural Beliefs

CG84 - APPENDIX 1 RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL BELIEFS As death When death is Immediately Method of Funeral Mourning approaches imminent after death disposal customs practices Buddhism Resuscitation is an The ideal way to die No special There is no one The funeral usually There is great acceptable procedure in a fully conscious requirements Buddhist death takes place within variation according for Buddhists, but and calm state of relating to the care ritual, type of 3 -7 days; a service to the country of some traditions have mind. of the body; funeral or afterlife may take place origin, e.g. Sri special needs as Buddhists from requirement. within the house Lankan Buddhist death approaches. Dying Buddhists different countries prior to going to the mourners may To assist in the may request that a have their own Buddhists choose cemetery or return to work in passage to the next monk or nun be traditions. to bury or cremate crematorium. three or four days rebirth, which is not present to chant or according to local and place no the same as assist in the passing If monks or traditions. Monks may be religious reincarnation, from this life. religious teacher invited to remind restrictions on wholesome acts such not present, inform Cremation is often the mourners of the widows. as generosity, If a monk is not the monks of the preferred as the impermanence of service, kindness or available a fellow appropriate school. body is considered life. Some Vietnamese pleasant thoughts are Buddhist may chant a vehicle that is Buddhists have a recalled. to encourage a Because rebirth is impermanent. -

Last Offices Policy February 2009 Reference Number: Corp09/002

Last Offices Policy February 2009 Reference Number: Corp09/002 Implementation Date: February 2009 Review Date: February 2011 Responsible Officer: Assistant Director of Nursing for Governance, Quality & Performance Last Offices Policy Page 2 of 19 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 4 Scope ........................................................................................................ 4 Definition ................................................................................................... 5 Aim ........................................................................................................... 5 Objectives .................................................................................................. 5 If Death is Imminent ................................................................................... 5 Sudden Unexpected Death ........................................................................... 6 Spiritual Needs ........................................................................................... 7 Relatives Viewing / Visiting the Deceased Patient. ........................................... 7 Requests to View the Deceased After the Body Has Left the Ward. .................... 8 Verification of Death .................................................................................... 8 Certification of the Death ............................................................................. 8 Registration of -

Care After Death and Bereavement Policy: Operational Policy for Staff to Follow in the Event of a Patient Death

PAT/T 60 v.2 Care after Death and Bereavement Policy: Operational Policy for Staff to follow in the event of a Patient Death This procedural document supersedes: PAT/T 60 v.1 (amended) – Death of a Patient Did you print this document yourself? The Trust discourages the retention of hard copies of policies and can only guarantee that the policy on the Trust website is the most up-to-date version. If, for exceptional reasons, you need to print a policy off, it is only valid for 24 hours. Executive Sponsor(s): Moira Hardy – Directory of Nursing, Midwifery and Quality Author/reviewer: (this Mandy Dalton. Mortality Review Lead version) Date written/revised: June 2018 Approved by: Policy Approval and Compliance Group Date of approval: 5 July 2018 Date issued: 9 July 2018 Next review date: June 2021 Target audience: All staff involved following the death of a patient - Trust wide Page 1 of 38 PAT/T 60 v.2 Amendment Form Please record brief details of the changes made alongside the next version number. If the procedural document has been reviewed without change, this information will still need to be recorded although the version number will remain the same. Version Date Issued Brief Summary of Changes Author Version 2 9 July 2018 This policy has been re-formatted into new Mandy Dalton APD template. Changes made to viewing arrangements Notification of GP Completion of Medical Certificate of Cause of Death) (MCCD) Version 1 30 Oct 2015 Due to changes in the Standard Operating Mark Boocock (amended) Procedure for the reporting of deaths occurring at Bassetlaw District General hospital to Her Majesty’s Coroner for Nottinghamshire. -

Multi Faith Booklet

Thomas Drive Liverpool L14 3PE Tel: 0151 600 1616 Fax: 0151 600 1862 www.lhch.nhs.uk Department of Spiritual Care Multi-Faith Book Meeting the Religious Needs of Patients & Families CONTENTS PAGE NO The Individual 3 The Anglican/Church of England Patient 6 The Roman Catholic Patient 8 The Free Church Patient 10 The Baha’i Patient 12 The Buddhist Patient 14 The Christian Scientist Patient 16 The Hari Krishna Patient 17 The Hindu Patient 18 The Humanist Patient 20 The Jain Patient 22 The Jehovah’s Witness Patient 24 The Jewish Patient 26 The Mormon Patient 28 The Muslim Patient 29 The Pagan Patient 31 The Rastafarian Patient 32 The Religious Society of Friends Patient 34 The Seventh Day Adventist Patient 35 The Shinto Patient 36 The Sikh Patient 37 The Spiritualist Patient 39 The Zoroastrian Patient 40 Culture 41 Local Directory of Faiths 43 National Contacts 45 Other Useful Contacts 50 2 V2 Reviewed February 2016 Patient & Family Support Team The Individual This information is intended as a guideline, and the most important point is to ask the individual (and/or their family) what is needed and what staff should be aware of. Whatever religious or cultural beliefs a patient has, they will have preferences and needs which are individual and personal to them alone. The individual has a right to have these wishes respected as long as this is possible and does not impose excessively on the rights of others. Everyone has spiritual needs, some of which may be expressed in an explicitly religious form. These needs may basically be expressed as: The right to love and be loved The need for meaning and purpose in life The need to feel worthwhile and be respected Glossary – an Explanation of Terms While often taken as synonymous, “culture”, “ethnicity” and “religion” express different concepts. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology by JW

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology by J. W. Mackail Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology by J. W. Mackail [We have both a 7 bit version and an 8 bit version. The 7 bit version does not contain accents, the 8 [binary] bit version does] This is the 8 bit version. SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY By J. W. Mackail First Published 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co. Etext prepared by John Bickers, [email protected] and Dagny, [email protected] SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY EDITED WITH A REVISED TEXT, TRANSLATION, AND NOTES BY page 1 / 371 J. W. MACKAIL Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER'S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. {eti pou proima leuxoia} Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil'd, Like the soil'd tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather'd, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. page 2 / 371 PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. -

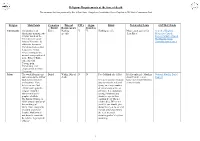

Religious Requirements at the Time of Death

Religious Requirements at the time of death This document has been produced by Rev’d Dom Jones, Hampshire Constabulary Force Chaplain & LRF Faith Communities Link Religion Main Points Cremation Funeral PM’s Organ Ritual Noteworthy Points COVID-19 Links / Burial Requirements Donation Christianity Christianity is an Either Nothing Y Y Nothing specific May request a priest for Church of England Abrahamic monotheistic specific ‘Last Rites’ Methodist Church religion based on the Roman Catholic Church life and teachings of The Baptist Union Jesus of Nazareth. Its United Reform Church adherents, known as Christians, believe that Jesus is the Christ, whose coming as the messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible, called the Old Testament in Christianity, and chronicled in the New Testament Islam The word Islam means Burial Within 24hr of N N Face Makkah (the Qibla) Ideally only male Muslims National Muslim Burial submission to the will of death should handle a male Council God and its followers It is an important religious body, and female Muslims are Muslims. They duty to visit the sick and a female body. believe in one God dying, so a large number (Allah) and regard the of visitors may arrive at religion’s founder all hours. It is customary Mohammed as the among Pakistanis and prophet of Allah. Arabs to express their The Koran (Quran), is emotion freely when a Allah’s word consists of relative dies. Whenever the teachings of possible you should give Islam. This, along with them privacy to do so; and recorded sayings of explain gently but firmly Prophet Mohammed the need to avoid and his acts, constitute disturbing other’s by their the Islamic legal system mourning. -

Last Offices Care of the Deceased UHL Policy

Last Offices Care of the Deceased UHL Policy Approved by: Policy & Guideline Committee Date Approved: 13 August 2010 Trust Reference: B28/2010 Version: 4 – PGC 3 June 2016 Supersedes: V3 Author / Jeanette Halborg Head of Nursing Clinical Originator(s): Support and Imaging Mark Burleigh Head Of Chaplaincy and Bereavement Services Name of Responsible Last Offices Care of the Deceased Patient Policy Committee/Individual: Task and Finish Group/End of Life and Palliative Care Committee Latest Review Date 3 June 2016 Next Review Date: May 2022 – Review Date Extension Approved at PGC 21.05.2021 CONTENTS Section Page 1 Introduction 3 2 Policy Aims 3 3 Policy Scope 3 4 Definitions 3 5 Roles and Responsibilities 4 6 Policy Statements, Standards, Procedures, Processes and Associated 5 Documents 7 Education and Training 5 8 Process for Monitoring Compliance 5 9 Equality Impact Assessment 6 10 Legal Liability 6 11 Supporting References, Evidence Base and Related Policies 6 12 Process for Version Control, Document Archiving and Review 7 Appendices Page One Declaring life extinct 10 Two Actions to be taken for suspicious death 12 Three Review referral to and contact with H.M. Coroner 14 Four Communication with the family 20 Five Post-mortem examination/taking tissue samples after death 25 Six Removal of Endotracheal Tubes (ET) 30 Seven Preparation of the deceased adult (“Last Offices”) 31 Eight Preparation of the deceased child (“Last Offices”) 38 Nine Transfer to the mortuary 46 Ten Risk of infection and use of body bags 54 Eleven Cultural and religious requirements 58 REVIEW DATES AND DETAILS OF CHANGES MADE DURING THE REVIEW V4 - review of V3 in May 2016, reformatted into latest Trust template. -

Guidance for Staff Responsible for Care After Death (Last Offices)

National Nurse Consultant Group (Palliative Care) Guidance for staff responsible for care after death (last offices) Developed by the National End of Life Care Programme and National Nurse Consultant Group (Palliative Care) The Royal College of Pathologists Pathology: the science behind the cure Contents 1 Foreword 2 Introduction 4 Pathways of care for the deceased person 5 Care before death 6 Care at the time of death 7 Best practice and legal issues 8 Care after death 10 Personal care after death 12 Transfer of the deceased person 13 Recording care after death 14 Glossary 14 Appendix 1: deaths requiring coronial investigations 15 Appendix 2: information required by mortuary staff and funeral directors 15 Appendix 3: key stakeholders involved in the development of this guidance To be reviewed: April 2014 Foreword Caring for a person at the end of their life, individuals – representing all organisations and after death, is enormously important and with a responsibility for caring for people a privilege. There is only one chance to get after death – have demonstrated a willingness it right and it is not at all easy to coordinate to work together and share professional everything that needs to happen. This expertise. We view these people as our guidance will help with that. partners in this work and they have shaped a cogent and cohesive pathway for delivery The DH End of Life Care Strategy (2008) for of care after death that honours the integrity England set out a pathway of care covering and wishes of the person who has died. each step in the end of life care journey. -

Fall 2020, Kumhera

Fall 2020, Kumhera Table of Contents Year Author and Title Page ca.1780 BCE Hammurabi’s Code of Laws………………………………………………. 3 ca.2300 BCE The Epic of Gilgamesh, selections………………………………………..... 8 ca.1950 BCE The Book of the Dead, “Judgment of the Dead”…………………………… 19 ca.950 BCE Selections from the Book of Genesis………………………………………..26 950-450 BCE Selections from Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy……..……………….35 600-550 BCE Selections from the First Book of Kings…………………………………… 42 750-700 BCE Homer, excerpts from the Odyssey, Book 11……………………………….48 ca.700 BCE Hesiod, selections from Works and Days……………………………….…..50 ca.650 BCE Tyrtaeus, Selection of Lyric Poems…………………………………………55 ca.380 BCE Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, Book 1…………………. 58 ca.100 CE Plutarch, selections from the Life of Lycurgus…………………………….. 60 ca.411 BCE Thucydides, “Pericles’ Funeral Oration” from The History of the Peloponnesian War………………………………………………… 63 ca.440 BCE Sophocles, Antigone……………………………………………………….. 68 ca.360 BCE Plato, selection from the Phaedo ………………………………………….. 93 ca.385 BCE Plato, selection from the Symposium………………………………………. 98 ca.340 BCE Aristotle, selection from The Politics…………………………………….... 102 ca.130 CE Arrian, selections from History of Alexander the Great……………………108 ca.146 BCE Polybius, “Analysis of Roman Government” from History……………….. 113 14 CE Augustus, The Deeds of the Divine Augustus……………………………… 118 ca.75 CE Pliny the Elder, selection from Natural History………………………….... 123 ca.100 CE Juvenal, Satire 6…………………………………………….……………... 125 2 CE Ovid, selections from The Art of Love…………………………………….. 128 18BCE-9 CE Augustus’ Marriage Legislation…………………………………………….136 ca.70 CE Selections from the Gospel according to Matthew ……………………….. 139 ca.90 CE Selections from the Gospel according to John……………………………. -

Spiritual Care

The following section gives brief guidelines on care for patients from Ethnic Minority backgrounds as well as from different faith-traditions. These seek to draw staff's attention to some relevant points pertinent to the care patients receive while being a patient within the Hospital. Further information or advice can be sought where necessary from the Trust's Religious and Culture Policy from the Hospital's Administration or the Hospital Chaplaincy Team. AFRO-CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY the main religion is some form of Christianity usually Anglican, Methodist and Pentecostal. prayer is important for those who are regular churchgoers : the opportunity of privacy for prayer and even hymn-singing, would be appreciated. Families often feel emotionally-restricted and inhibited in hospitals in the United Kingdom. Ward staff should anticipate the need for a single room for a dying patient as visitors are important to the dying person. Family will probably not give consent for a post-mortem examination as the body must be intact for after-life and will therefore be deeply offended by its disfigurement. no religious objection to others handling the body as long as respect is shown at all times. BUDDHISTS may seek counselling from a fellow Buddhist or seek the help of the Hospital Chaplain in arranging for a time of peace and quiet for meditation. some form of chanting from the patient's family and friends may be used to influence the state of mind at death so that it may be peaceful. are encouraged to meditate for as long as they are able, resist unconsciousness. Because wakefulness is important drugs which may depress the C.N.S.