Issn 0017-0615 the Gissing Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Beautiful in Books TO

THE WORLD BEAUTIFUL IN BOOKS BY LILIAN WHITING Author of " The World Beautiful," in three volumes, First, Second, " " and Third Series ; After Her Death," From Dreamland Sent," " Kate Field, a Record," " Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning," etc. If the crowns of the world were laid at my feet in exchange for my love of reading, 1 would spurn them all. — F^nblon BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY ^901 PL Copyright, 1901, By Little, Brown, and Company. All rights reserved. I\17^ I S ^ November, 1901 UNIVERSITY PRESS JOHN WILSON AND SON • CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A. Lilian SMIjttins'fii glMoriiB The World Beautiful. First Series The World Beautiful. Second Series The World Beautiful. Third Series After her Death. The Story of a Summer From Dreamland Sent, and Other Poems A Studv of Elizabeth Barrett Browning The Spiritual Significance Kate Field: a Record The World Beautiful in Books TO One whose eye may fall upon these pages; whose presence in tlie world of thought and achievement enriches life ; whose genius and greatness of spirit inspire my every day with renewed energy and faith, — this quest for " The World Beautiful" in literature is inscribed by LILIAN WHITING. " The consecration and the poeVs dream" CONTENTS. BOOK I. p,,. As Food for Life 13 BOOK II. Opening Golden Doors 79 BOOK III. The Rose of Morning 137 BOOK IV. The Chariot of the Soul 227 BOOK V. The Witness of the Dawn 289 INDEX 395 ; TO THE READER. " Great the Master And sweet the Magic Moving to melody- Floated the Gleam." |0 the writer whose work has been en- riched by selection and quotation from " the best that is known and thought in* the world," it is a special pleasure to return the grateful acknowledgments due to the publishers of the choice literature over whose Elysian fields he has ranged. -

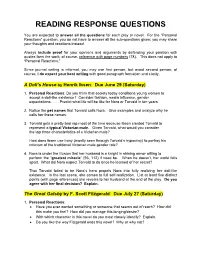

Reading Response Questions

READING RESPONSE QUESTIONS You are expected to answer all the questions for each play or novel. For the “Personal Reactions” question, you do not have to answer all the sub-questions given; you may share your thoughts and reactions instead. Always include proof for your opinions and arguments by defending your position with quotes form the work; of course, reference with page numbers (78). This does not apply to “Personal Reactions.” Since journal writing is informal, you may use first person, but avoid second person; of course, I do expect your best writing with good paragraph formation and clarity. A Doll’s House by Henrik IBsen: Due June 29 (Saturday) 1. Personal Reactions: Do you think that society today conditions young women to accept a doll-like existence? Consider fashion, media influence, gender expectations . Predict what life will be like for Nora or Torvald in ten years. 2. Notice the pet names that Torvald calls Nora. Give examples and analyze why he calls her these names. 3. Torvald gets a pretty bad rap most of the time because Ibsen created Torvald to represent a typical Victorian male. Given Torvald, what would you consider the top three characteristics of a Victorian male? How does Ibsen use irony (mostly seen through Torvald’s hypocrisy) to portray his criticism of the traditional Victorian male gender role? 4. Nora is under the illusion that her husband is a knight in shining armor willing to perform the “greatest miracle” (93, 112) if need be. When he doesn’t, her world falls apart. What did Nora expect Torvald to do once he learned of her secret? That Torvald failed to be Nora’s hero propels Nora into fully realizing her doll-like existence. -

ISSN 0017-0615 the GISSING JOURNAL “More Than Most Men Am I Dependent on Sympathy to Bring out the Best That Is in Me.”

ISSN 0017-0615 THE GISSING JOURNAL “More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me.” – George Gissing’s Commonplace Book. ********************************** Volume XXX, Number 2 April, 1994 ********************************** Contents London Homes and Haunts of George Gissing: An 1 Unpublished Essay by A. C. Gissing, edited by Pierre Coustillas and Xavier Pétremand The Critical Response to Gissing and Commentary about 15 him in the Chicago Evening Post (concluded), by Robert L. Selig Book Reviews, by Bouwe Postmus, Jacob Korg and Pierre Coustillas 22 Thesis Abstract, by Chandra Shekar Dubey 24 Notes and News 36 Recent Publications 39 -- 1 -- London Homes and Haunts of George Gissing An Unpublished Essay by A. C. Gissing Edited by Pierre Coustillas and Xavier Pétremand In our introduction to “George Gissing and War,” which was printed in the January 1992 number of this journal, we mentioned the existence of two other unpublished essays by Alfred Gissing, “Frederic Harrison and George Gissing” and “London Homes and Haunts of George Gissing.” The three of them were doubtless written in the 1930s when he lived with his sole surviving aunt Ellen at Croft Cottage. Alfred did not date these essays, but they all carry his address of the period – Barbon, Westmorland, via Carnforth. Although they were less ambitious pieces than the articles he published in the National Review in August 1929 and January 1937, they were doubtless intended for publication; yet there is no evidence available that their author tried to find them a home in magazines such as T.P.’s Weekly or John o’ London’s Weekly, which sought to offer cultural entertainment and information to a public that cared for literature and any easily digestible comment on writers’ lives and works. -

Andover-1913.Pdf (7.550Mb)

TOWN OF ANDOVER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Receipts and Expenditures ««II1IUUUI«SV FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JANUARY 13, 1913 ANDOVER, MASS. THE ANDOVER PRESS *9 J 3 CONTENTS Almshouse Expenses, 7i Memorial Day, 58 Personal Property at, 7i Memorial Hall Trustees' Relief of, out 74 Report, 57, 121 Repairs on, 7i Miscellaneous, 66 Superintendent's Report, 75 Moth Suppression, 64 Animal Inspector, 86 Notes Given, Appropriations, 1912, 17 58 Art Gallery, 146 Notes Paid, 59 Assessors' Report 76 Overseers of Poor, 69 Assets, 93 Park Commissioner, 56 Auditor's Report, 105 Park Commissioners' Report 81 Board of Health, 65 Playstead, 55 Board of Public Works, Appen dix, Police, 53, 79 Sewer Maintenance, 63 Sewer Sinking Funds, 63 Printing and Stationery, 55 Water Maintenance, 62 Punchard Free School, Report Water Construction, 63 of Trustees, 101 Water Sinking Funds, 63 Repairs on old B. V. School, 68 Bonds, Redemption of, 62 Schedule of Town Property, 82 Collector's Account, 89 Schoolhouses, 29 Cornell Fund, 88 Schools, 23 County Tax, 56 School Books and Supplies, 3i Daughters of Revolution 68 Dog Tax 56 Selectmen's Report, 23 Dump, care of 58 Sidewalks, 42 Earnings Town Horses, 48 Soldiers' Relief, 74 Elm Square Improvements, 43 Snow, Removal of, 43 Fire Department, 51 77 Spring Grove Cemetery, 57, 87 Haggett's Pond Land, 68 State Aid, 74 Hay Scales, 58 State Tax, 55 Highways and Bridges, 33 Street Lighting, 50 Highway Surveyor, 46 Street List, 109 Horses and Drivers, 4i Town House, 54 Insurance, 63 Town Meeting, 7 Interest on Notes and Funds, 59 Town Officers, Liabilities, ior 4, 49 Town Warrant, 117 Librarian's Report, 125 Account, Macadam, 35 Treasurer's 93 Andover Street, 37 Tree Warden, 50 Salem Street, 39 Report, 85 TOWN OFFICERS, 1912 Selectmen, Assessors and Overseers of the Poor HARRY M. -

Place and Class in George Gissing' S "Slum" Novels, Part I, by Pat Colling 3

Contents Knowing Your Place: Place and Class in George Gissing' s "Slum" Novels, Part I, by Pat Colling 3 Gissing Reviewed on Amazon, by Robin Friedman 19 Notes and News 42 Recent Publications 43 ISSN 017-0615 The Gissing Journal Volume 50, Number 1,January 2014 "More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me." Commonplace Book Knowing Your Place: Place and Class in George Gissing's "Slum" Novels, Part 1 PAT COLLING The Gissing Trust Between 1880 and 1889 five of Gissing' s seven novels Workers in the Dawn (1880), The Unclassed (1884), Demos (1886), Thyrza (1887), and The Nether World (1889)--were set in deprived neighbourhoods. All were concerned with life in penury, and had major characters who were working class. Contemporarynovelists and readers tended to see the poor as a cause; by the time Thyrza was published in 1887 George Gissing did not. By then he was not romanticising the working classes, nor presenting them as victims, nor necessarily as unhappy, and in this he can seem, to the reader expecting the established Victorian norm of philanthropic compassion, uncaring, even contemptuous. But his distinct representation of the poor-good, bad, and average-as they are, in the same way that novelists were already presenting the middle and upper classes, is respectfulrather than jaundiced. He sees them as individuals with differing characteristics, values, abilities, and aspirations, not as a lumpenproletariat in need of rescue and redemption. Gissing goes further than other novelists in 3 being willing to criticise the inhabitants as well as the slums, and he differs from them in his frequent presentation of the family as a scene of conflict rather than as the more familiar Victorian ideal of refuge. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

The Gissing Newsletter

THE GISSING NEWSLETTER “More than most men am I dependent on sympathy to bring out the best that is in me.” – George Gissing’s Commonplace Book. ********************************** Volume IX, Number 4 October, 1973 ********************************** -- 1 -- The Guilty Secret Gillian Tindall [This is an extract from chapter III of a book about Gissing to be published next spring by Maurice Temple Smith in London and probably by Harcourt Brace in America. The title, the author told me some months ago, is to be George Gissing, Writer. Gillian Tindall has made herself an enviable reputation among modern English novelists with a number of stories like The Youngest, Someone Else and Fly Away Home, the last of which was awarded the 1972 Somerset Maugham Award. She recently published a collection of short stories, Dances of Death (Hodder & Stoughton). There have been translations of her novels into Polish, Italian and French. – P.C.] *************************************************** Editorial Board Pierre Coustillas, Editor, University of Lille Shigeru Koike, Tokyo Metropolitan University Jacob Korg, University of Washington, Seattle Editorial correspondence should be sent to the editor: 10, rue Gay-Lussac, 59110-La Madeleine, France, and all other correspondence to: C. C. KOHLER, 141 High Street, Dorking, Surrey, England. Subscriptions Private Subscribers: £1.00 per annum Libraries: £1.50 per annum *************************************************** -- 2 -- Of the various personal themes which run like significant, persistent yet often irrelevant threads through Gissing’s novels and stories, that of the Guilty Secret is perhaps the most ubiquitous and at the same time the most elusive. You can read a number of his books before even spotting it as a theme, yet, once noticed, it makes its presence felt everywhere. -

Mitsuharu Matsuoka, Ed

Mitsuharu Matsuoka, ed., Society and Culture in the Late Victorian Age with Special Reference to Gissing: In the Year of the Sesquicentennial of His Birth, Hiroshima: Keisuisha, 2007. xiii+540 pp. In commemoration of the sesquicentennial of Gissing’s birth, a substan- tial study of the long-neglected novelist and his era was issued last year in Japan. The late Victorian age is analyzed from five angles—society, era, gender, author, and ideologies—Gissing constituting the core of the socio- cultural study. The book is no doubt a treasure trove of knowledge. The following are summaries of the 26 chapters, including the biographical introduction: Pierre Coustillas’s Introduction consists in a short biography of Gissing (trans. by Mitsuharu Matsuoka) whom he sees as a man of two worlds: the world of bitter destitution and frustration which he was forced to endure, and the world of classical literature in which his imagination sought a refuge. He then surveys Gissing’s life, incorporating biographical facts in chronological order. The reader is reminded that, in Japan, Gissing’s value was first recognized by the intelligentsia of the 1920s and the author con- cludes his account by observing that the genial, shy, and altruistic Gissing was a pacifist and humanistic intellectual who represented the conscience of his time. Part One: Society. In Chapter 1: “Education: Form and Substance,” Shigeru Koike first argues that the reform of the educational system in 19th- century England was intended to emphasize the importance of scientific methodologies, and then discusses Workers in the Dawn, Born in Exile, The Emancipated, and New Grub Street as images of Gissing’s view of educa- tion. -

George Gissing and the Place of Realism

George Gissing and the Place of Realism George Gissing and the Place of Realism Edited by Rebecca Hutcheon George Gissing and the Place of Realism Edited by Rebecca Hutcheon This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Rebecca Hutcheon and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6998-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6998-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Rebecca Hutcheon Chapter 1 .................................................................................................. 14 George Gissing, Geographer? Richard Dennis Chapter 2 .................................................................................................. 36 Workers in the Dawn, Slum Writing and London’s “Urban Majority” Districts Jason Finch Chapter 3 .................................................................................................. 55 Four Lady Cyclists José Maria Diaz Lage Chapter 4 .................................................................................................. 70 Gissing’s Literary -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Notes

How to Read Literature Like a Professor (Thomas C. Foster) Notes Introduction Archetypes: Faustian deal with the devil (i.e. trade soul for something he/she wants) Spring (i.e. youth, promise, rebirth, renewal, fertility) Comedic traits: tragic downfall is threatened but avoided hero wrestles with his/her own demons and comes out victorious What do I look for in literature? - A set of patterns - Interpretive options (readers draw their own conclusions but must be able to support it) - Details ALL feed the major theme - What causes specific events in the story? - Resemblance to earlier works - Characters’ resemblance to other works - Symbol - Pattern(s) Works: A Raisin in the Sun, Dr. Faustus, “The Devil and Daniel Webster”, Damn Yankees, Beowulf Chapter 1: The Quest The Quest: key details 1. a quester (i.e. the person on the quest) 2. a destination 3. a stated purpose 4. challenges that must be faced during on the path to the destination 5. a reason for the quester to go to the destination (cannot be wholly metaphorical) The motivation for the quest is implicit- the stated reason for going on the journey is never the real reason for going The real reason for ANY quest: self-knowledge Works: The Crying of Lot 49 Chapter 2: Acts of Communion Major rule: whenever characters eat or drink together, it’s communion! Pomerantz 1 Communion: key details 1. sharing and peace 2. not always holy 3. personal activity/shared experience 4. indicates how characters are getting along 5. communion enables characters to overcome some kind of internal obstacle Communion scenes often force/enable reader to empathize with character(s) Meal/communion= life, mortality Universal truth: We all eat to live, we all die. -

Henry James and Romantic Revisionism: the Quest for the Man of Imagination in the Late Work

HENRY JAMES AND ROMANTIC REVISIONISM: THE QUEST FOR THE MAN OF IMAGINATION IN THE LATE WORK A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (OF ENGLISH ) By Daniel Rosenberg Nutters May 2017 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Alan Singer, English Steve Newman, English Robert L. Caserio, External Member, Pennsylvania State University Jonathan Arac, External Member, University of Pittsburgh © Copyright 2017 by Daniel Rosenberg Nutters All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This study situates the late work of Henry James in the tradition of Romantic revisionism. In addition, it surveys the history of James criticism alongside the academic critique of Romantic-aesthetic ideology. I read The American Scene, the New York Edition Prefaces, and other late writings as a single text in which we see James refashion an identity by transforming the divisions or splits in the modern subject into the enabling condition for renewed creativity. In contrast to the Modernist myth of Henry James the master reproached by recent scholarship, I offer a new critical fiction – what James calls the man of imagination – that models a form of selfhood which views our ironic and belated condition as a fecund limitation. The Jamesian man of imagination encourages the continual (but never resolvable) quest for a coherent creative identity by demonstrating how our need to sacrifice elements of life (e.g. desires and aspirations) when we confront tyrannical circumstances can become a prerequisite for pursuing an unreachable ideal. This study draws on the work of post-war Romantic revisionist scholarship (e.g. -

2010 Exam Day Lunch Schedule

Ontario H. S. 2016-17 English Department Reading Material Freshmen Books: Summer: Animal Farm School Year: To Kill a Mockingbird Romeo and Juliet The Odyssey Sophomore Books Summer: Of Mice and Men ...alternative The Pearl Honors: Summer: The Hunger Games by Collins Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card School Year: Dover Thrift edition of Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton Dover Thrift edition of Bullfinch's Mythology Julius Caesar by Shakespeare Lord of the Flies by William Golding Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes Twelve Angry Men by Reginald Rose A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah Junior Books: Summer: Celia Garth by Gwen Bristow Recommended- not required: Celebrate Liberty! Famous Patriotic Speeches and Sermons Complied by David Barton Thomas Paine’s Common Sense School Year: 1984 by Orwell The Scarlet Letter by Hawthorne The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Twain The Athena Project by Brad Thor Anthem by Ayn Rand Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand Salem’s Lot by Stephen King Advanced Placement: The Language of Composition: Reading. Writing. Rhetoric by Shea(2013) 5 Steps to a 5 AP English Language : McGraw Hill American Literature opposite College Credit +: Celia Garth by Gwen Bristow Senior Books: Summer: No Fear Shakespeare: Hamlet by Shakespeare School Year: Dover Thrift edition of Daisy Miller by James Dover Thrift Edition of A Doll’s House by Ibsen Dover Thrift Edition of Metamorphosis by Kafka Dover Thrift edition of The Importance of Being Ernest by Wilde Novel of Choice from the Multi-Genre book list (200+ books) Textbook: Literature