Chapter 2. Economic Impact of Remittances from Migrants On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix J.2.3)

Supplementary Appendix H.1 NORTHWEST IRRIGATION SECTOR PROJECT LINK CANAL SUBPROJECT RESETTLEMENT PLAN List of Contents Page 1. The Project 3 2. Impact on Structures and Land Acquisition 4 3. Mitigating Project Impact 5 4. Socio-Economic Situation in the Project Area. 6 4.1 Project Socioeconomic Surveys 6 4.2 Socio-Economic Characteristics Of The Wider Project Area 6 5. Objectives, Policy Framework and Entitlements 16 6. Mitigating Impact and Ensuring the Restoration of Livelihoods of APs 18 7. Participation, Information and Consultation and Grievance Redress 21 7.1 AP Participation 21 7.2 Disclosure of Information to APs 21 7.3 The Grievance Process 22 8. Management and Organisation 24 9. Resettlement Budget 26 10.Implementation Schedule 28 11.Monitoring and Evaluation 28 List of Tables: Number Title Page No. 3.1 Development Agents Working in Area 7 4.1 Demographics of Subproject Area 8 4.2 Village Demographics 8 4.3 Age-Sex distribution of APs 9 4.4 Size of AP households 9 4.5 Incidence of Overall Poverty in Subproject Area 9 4.6 APs Deficit in rice production for household 9 4.7 APs Duration of Rice Deficit last year (months) 9 4.8 Literacy of household head and spouse 10 i Supplementary Appendix H.1 4.9 School attendance of children of primary school age 10 4.10 Reason for non-attendance school 10 4.11 Attendance of school age children: Lower secondary 10 4.12 Reason for non-attendance at secondary school 10 4.13 Village Land, Farming System, Non-Farming Occupations and Mines or UXO Pesence 12 4.14 Bavel District, Kdol Commune, Villages -

General Population Census of Cambodia 1998 Final Census Results

KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA Nation - Religion - King General Population Census of Cambodia 1998 Final Census Results (2nd Edition) National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning Phnom Penh, Cambodia Funded by: United Nations Population Fund August, 2002 CONTENTS Page Foreword by HE Minister of Planning 3 Foreword by UNFPA Representative, Cambodia 5 Cambodia-Province Map 6 Figures at a Glance 7 SECTION 1- Introduction 10 SECTION 2- Brief Analysis of Final Census Results of Cambodia 17 GLOSSARY 37 SECTION 3- Census Tables 41 Cambodia 42 Provinces / Municipalities (with Analytical Notes) 45 01. Banteay Mean Chey 46 02. Bat Dambang 56 03. Kampong Cham 67 04. Kampong Chhnang 80 05. Kampong Spueu 91 06. Kampong Thum 102 07. Kampot 113 08. Kandal 124 09. Kaoh Kong 136 10. Kracheh 146 11. Mondol Kiri 156 12. Phnom Penh Municipality 165 13. Preah Vihear 176 14. Prey Veaeng 186 15. Pousat 198 16. Rotanak Kiri 208 17. Siem Reab 218 1 18. Krong Preah Sihanouk 229 19. Stueng Traeng 238 20. Svay Rieng 248 21. Takaev 259 22. Otdar Mean Chey 270 23. Krong Kaeb 279 24. Krong Pailin 288 Annexes Annex 1- Form A - Houselisting and 297 Form B - Households Questionnaires 298 Annex 2- List of Priority Tables 302 Annex 3- Publication Programme 304 2 TOC FOREWORD By HE Minister of Planning, Cambodia It is with great pleasure that I present this report containing the final population figures and some important results of the 1998 Census of Cambodia. Earlier, in August 1998, the provisional population figures were released based on a quick tabulation of summary figures provided by the enumerators. -

Quarterly Report #21 Helping Address Rural Vulnerabilities and Ecosystem Stability (Harvest) Program

Prepared by Fintrac Inc. QUARTERLY REPORT #21 HELPING ADDRESS RURAL VULNERABILITIES AND ECOSYSTEM STABILITY (HARVEST) PROGRAM January – March 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Fintrac Inc. under contract # AID-442-C-11-00001 with USAID/Cambodia. HARVEST ANNUAL REPORT #1, DECEMBER 2010 – SEPTEMBER 2011 1 Fintrac Inc. www.fintrac.com [email protected] US Virgin Islands 3077 Kronprindsens Gade 72 St. Thomas, USVI 00802 Tel: (340) 776-7600 Fax: (340) 776-7601 Washington, D.C. 1400 16th St. NW, Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20036 USA Tel: (202) 462-8475 Fax: (202) 462-8478 Cambodia HARVEST No. 34 Street 310 Sangkat Beong Keng Kang 1 Khan Chamkamorn, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tel: 855 (0) 23 996 419 Fax: 855 (0) 23 996 418 QUARTERLY REPORT #21 HELPING ADDRESS RURAL VULNERABILITIES AND ECOSYSTEM STABILITY (HARVEST) PROGRAM January – March 2016 The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Program Description ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Geographic Focus ........................................................................................................................................... -

Kamping Pouy Subproject

Irrigated Agriculture Improvement Project (RRP CAM 51159-002) Feasibility Study Report November 2019 Cambodia: Irrigated Agriculture Improvement Project Kamping Pouy Subproject Prepared by the Pacific Rim Innovation and Management Exponents, Inc. on behalf of the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). FEASIBILITY STUDY REPORT: KAMPING POUY SUBPROJECT Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables iii List of Figures v List of Appendixes vi List of Abbreviations vii Executive Summary ix I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. SUBPROJECT ASSESSMENT 4 A. Review of Current Situation and Options for Improvement and Modernization 4 B. Proposal for System Modernization 9 C. Proposed Civil Works for System Modernization, Option 2 14 III. HYDROLOGY AND WATER AVAILABILITY 17 A. Introduction 17 B. Rainfall 18 C. Evaporation 18 D. Runoff from Kamping Pouy Reservoir Catchment 19 E. Diversion Flow from Mongkol Borey River 20 F. Reservoir Routing 22 G. Reservoir Balance 23 IV. AGRICULTURE 27 A. Current Farming Practices 27 B. Current Cropping Pattern 28 C. Soil Condition 28 D. Agro-inputs 29 E. Constraints to Yield and Field Recovery of Yield 30 F. Increasing Crop Production and Modernization of Irrigation Systems 30 G. Proposed Intensive Rice Cropping Pattern and Diversified Cropping System 31 H. Nutrient Management for Rice Production in Kamping Pouy 32 I. Proposed Cropping Pattern 32 J. Capacity Building 37 K. Economic Benefits 38 V. MANAGEMENT OF IMPROVED SYSTEM PERFORMANCE 40 A. Introduction 40 B. Main System Operation 40 C. Climate Proofing 46 D. On-farm Water Management (OFWM) 49 E. Irrigation Maintenance: Institutional Arrangements 53 F. -

Type of the Paper (Article

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 8 November 2016 doi:10.20944/preprints201611.0046.v1 Article An Analysis of Technical Efficiency for Household's Rice Production in Cambodia: A Case Study of Three Districts in Battambang Province Sokvibol Kea 1,2,*, Hua Li 1,* and Linvolak Pich 3 1 College of Economics and Management (CEM), Northwest A&F University, 712100 Shaanxi, China 2 Faculty of Sociology & Community Development, University of Battambang, 053 Battambang, Cambodia 3 College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering (CWRAE), Northwest A&F University, 712100 Shaanxi, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (H.L.); Tel.: +855-96-986-6668 (S.K.); +86-133-6393-6398 (H.L.) Abstract: The aims of this study are to measure the technical efficiency (TE) of Cambodian household’s rice production and trying to determine its main influencing factors using the stochastic frontier production function. The study utilized primary data collected from 301 rice farmers in three selected districts of Battambang by structured questionnaires. The empirical results indicated the level of household rice output varied according to differences in the efficiency of production processes. The mean TE is 0.34 which means that famers produce 34% of rice at best practice at the current level of production inputs and technology, indicates that rice output has the potential of being increased further by 66% at the same level of inputs if farmers had been technically efficient. Furthermore, between 2013-2015 TE of household’s rice production recorded -14.3% decline rate due to highly affected of drought during dry season of 2015. -

Technical Efficiency Analysis of Cambodian Household's Rice

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: E Economics Volume 16 Issue 3 Version 1.0 Year 2016 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Technical Efficiency Analysis of Cambodian Household's Rice Production By Sokvibol Kea, Hua Li & Linvolak Pich College of Economics and Management Abstract- The aims of this study are to measure the technical efficiency (TE) of Cambodian household’s rice production and its main influencing factors using SFA model. Primary data was collected from 301 rice farmers in three selected districts of Battambang by structured questionnaires. The empirical results indicated the mean TE is 0.34 which means famers produce 34% of rice at best practice at the current level of production inputs and technology, reveling that rice output has the potential of being increased further by 66% at the same level of inputs if farmers had been technically efficient. Evidence also reveals that land, fertilizer, and pesticide are the major influencing input factors of household’s rice production. However, between 2013 and 2015 TE recorded -14.3% decline rate due to highly affected of drought during dry season of 2015. Keywords: agricultural productivity, battambang, cambodia, rice production, stochastic frontier production function (sfa model), technical efficiency. GJHSS-E Classification: FOR Code: 149999 TechnicalEfficiencyAnalysisofCambodianHouseholdsRiceProduction Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2016. Sokvibol Kea, Hua Li & Linvolak Pich. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

RDJR0658 Paddy Market

Appendix Appendix 1: The selected 3 areas for feasibility study A-1 Mongkol Borei, Banteay Meanchey + Babel & Thma Koul, Battambang Koy Maeng Ruessei Kraok # N #Y# Feasibility Study Area Bat Trang Mongkol Borei Mongkol Borei, Bavel and Thma Koul Districts # # # Ta Lam # Rohat Tuek Srah Reang # Ou Prasat # # Chamnaom Kouk Ballangk # # Sambuor P# hnum Touch Soea # Boeng Pring # # Prey Khpo#s Lvea Chrouy Sdau # Thmar Koul Kouk Khmum Ta Meun Ampil Pram Daeum Khnach Romeas # # # # # # # Bansay TraenY#g# Bavel Y# Bavel Rung Chrey Ta Pung BANTEAY MEAN CHEY Kdol Ta Hae#n (/5 Ru ess ei K rao k #Ko y Ma en g # Bat Tr an g #Mong kol Borei Ta La m #Ban te ay #YNea ng # Anlong Run # Sra h Re a ng Roha t Tu e k # Ou Ta Ki # Kou k Ba l ang k #Ou Pras a t # Sa m bu o r Ch am n #aom # BANTEAY ME AN CHEY Phnu m To uc h # #So e a # Bo en g Pri ng Lve a Pre y Kh p#o s # # Chro u y Sd au BAT TAMB ANG # Kou k Kh mum Thma K ou l Kh nac h R om e as Ta Meu n Ampil Pra m Daeu m Bav e l Bans a y Tr aen g # Ru ng Ch#re y ## Ta Pu n g # Y#B#av el # Y# Chrey# # Kd ol T a Hae n BATTAMBANG An lon g Ru #n # Ou Ta K i # Chre y Provincial road 8 0 8 16 Kilometers National road Railway A-2 Moung Ruesssei, Battambang + Bakan, Pursat Feasibility Study Area N Moung Ruessei and Bakan Districts Prey Touch # Thipakdei # # Kakaoh 5 Ta Loas /( # Moung Ruessei # Chrey Moung Ruessei #Y# # Kear # Robas Mongkol Prey Svay # Ruessei Krang Me Tuek # # Svay Doun Kaev # # #Ou Ta Paong Preaek Chik Boeng Khnar # # Bakan Sampov Lun Boeng Bat Kandaol Trapeang Chong #Phnum Proek BATTAM BANG -

Battambang(PDF:320KB)

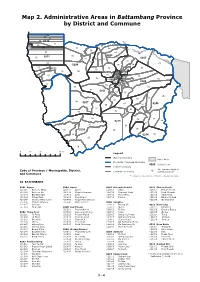

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 06 05 04 03 0210 01 02 07 04 03 04 06 03 01 02 06 0211 05 0202 05 01 0205 01 10 09 08 02 01 02 07 0204 05 04 05 03 03 0212 05 03 04 06 06 06 04 05 02 03 04 02 02 0901 03 04 08 01 07 0203 10 05 02 0208 08 09 01 06 10 08 06 01 04 07 0201 03 07 02 05 08 06 01 04 0207 01 0206 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 06 03 09 03 0213 04 02 07 04 01 05 0209 06 04 0214 02 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water Area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0211 Phnom Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 -

Comparison of Cambodian Rice Production Technical 2 Efficiency At

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 29 September 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201709.0161.v1 1 Article 2 Comparison of Cambodian Rice Production Technical 3 Efficiency at National and Household Level 4 Sokvibol Kea 1,2,*, Hua Li 1,* and Linvolak Pich 3 5 1 College of Economics and Management (CEM), Northwest A&F University, 712100 Shaanxi, China 6 2 Faculty of Sociology & Community Development, University of Battambang, 053 Battambang, Cambodia 7 3 College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering (CWRAE), Northwest A&F University, 712100 8 Shaanxi, China; [email protected] 9 * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (H.L.); Tel.: +855-96-986-6668 (S.K.); 10 +86-133-6393-6398 (H.L.) 11 Abstract: Rice is the most important food crop in Cambodia and its production is the most 12 organized food production system in the country. The main objective of this study is to measure 13 technical efficiency (TE) of Cambodian rice production and also trying to identify core influencing 14 factors of rice TE at both national and household level, for explaining the possibilities of increasing 15 productivity and profitability of rice, by using translog production function through Stochastic 16 Frontier Analysis (SFA) model. Four-years dataset (2012-2015) generated from the government 17 documents was utilized for the national analysis, while at household-level, the primary three-years 18 data (2013-2015) collected from 301 rice farmers in three selected districts of Battambang province 19 by structured questionnaires was applied. The results indicate that level of rice output varied 20 according to the different level of capital investment in agricultural machineries, total actual 21 harvested area, and technically fertilizers application within provinces, while level of household 22 rice output varied according to the differences in efficiency of production processes, techniques, 23 total annual harvested land, and technically application of fertilizers and pesticides of farmers. -

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune

Map 2. Administrative Areas in Battambang Province by District and Commune 06 05 04 03 0210 01 02 07 04 03 04 06 03 01 02 06 05 0202 05 0211 01 0205 01 10 09 08 02 01 02 07 0204 05 04 05 03 03 0212 05 03 04 06 06 06 04 05 02 03 04 02 02 0901 03 04 08 01 07 0203 10 05 02 0208 08 09 01 06 10 08 06 01 04 07 0201 03 07 02 05 08 06 01 04 0207 01 0206 05 07 02 03 03 05 01 02 06 03 09 03 0213 04 02 07 04 01 05 0209 06 04 0214 02 02 01 0 10 20 40 km Legend National Boundary Water Area Provincial / Municipal Boundary 0000 District Code District Boundary The last two digits of 00 Code of Province / Municipality, District, Commune Boundary Commune Code* and Commune * Commune Code consists of District Code and two digits. 02 BATTAMBANG 0201 Banan 0204 Bavel 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0211 Phnom Proek 020101 Kantueu Muoy 020401 Bavel 020701 Sdau 021101 Phnom Proek 020102 Kantueu Pir 020402 Khnach Romeas 020702 Andaeuk Haeb 021102 Pech Chenda 020103 Bay Damram 020403 Lvea 020703 Phlov Meas 021103 Chak Krey 020104 Chheu Teal 020404 Prey Khpos 020704 Traeng 021104 Barang Thleak 020105 Chaeng Mean Chey 020405 Ampil Pram Daeum 021105 Ou Rumduol 020106 Phnum Sampov 020406 Kdol Ta Haen 0208 Sangkae 020107 Snoeng 020801 Anlong Vil 0212 Kamrieng 020108 Ta Kream 0205 Aek Phnum 020802 Norea 021201 Kamrieng 020501 Preaek Norint 020803 Ta Pun 021202 Boeung Reang 0202 Thma Koul 020502 Samraong Knong 020804 Roka 021203 Ou Da 020201 Ta Pung 020503 Preaek Khpob 020805 Kampong Preah 021204 Trang 020202 Ta Meun 020504 Preaek Luong 020806 Kampong Prieng 021205 Ta Saen 020203 -

(UNRISD) Is an Autonomous Agency Engaging in Multi-Disciplinary Research on the Social Dimensions of Contemporary Problems Affecting Development

The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multi-disciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Business Responsibility for Sustainable Development; Emerging Mass Tourism in the South; Gender, Poverty and Well-Being; Globalization and Citizenship; Grassroots Initiatives and Knowledge Networks for Land Reform in Developing Countries; New Information and Communication Technologies; Public Sector Reform and Crisis-Ridden States; Technical Co-operation and Women’s Lives: Integrating Gender into Development Policy; and Volunteer Action and Local Democracy: A Partnership for a Better Urban Future. Recent research programmes have included: Crisis, Adjustment and Social Change; Culture and Development; Environment, Sustainable Development and Social Change; Ethnic Conflict and Development; Participation and Changes in Property -

EMR: Cambodia: Rural Roads Improvement Project

Environmental Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report January–June 2012 CAM: Rural Roads Improvement Project Consulting Services for Detailed Design and Implementation Supervisio Prepared by the Korea Consultants International in association with Filipinas Dravo Corporation for the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, the Kingdom of Cambodia, and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 July 2012) Currency unit – riel (KR) KR1.00 = $0.00024 $1.00 = KR4,082 NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA MINISTRY OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT ADB LOAN 2670-CAM (SF) RURAL ROADS IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Consulting Services for Detailed Design and Implementation Supervision (DDIS) SEMI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENT MONITORING REPORT AUGUST 2012 KOREA CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL in association with Filipinas Dravo Corporation CONTENTS DEFINITION AND ABBREVIATIONS BASIC DATA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LOCATION MAP OF PROJECT ROADS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. ENVIRONMENT MONITORING MECHANISM 3 2.1 Introduction 3 2.2 Environment Management Plan (EMP) 3 2.3 Environment Monitoring Program 3 2.4 Measurements 3 2.5 Timing of Monitoring 5 2.6 Monitoring of CEMP 5 3.