The Correctional Service of Canada's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

House & Senate

HOUSE & SENATE COMMITTEES / 63 HOUSE &SENATE COMMITTEES ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PRIVACY AND Meili Faille, Vice-Chair (BQ)......................47 A complete list of all House Standing Andrew Telegdi, Vice-Chair (L)..................44 and Sub-Committees, Standing Joint ETHICS / L’ACCÈS À L’INFORMATION, DE LA PROTECTION DES RENSEIGNEMENTS Omar Alghabra, Member (L).......................38 Committees, and Senate Standing Dave Batters, Member (CON) .....................36 PERSONNELS ET DE L’ÉTHIQUE Committees. Includes the committee Barry Devolin, Member (CON)...................40 clerks, chairs, vice-chairs, and ordinary Richard Rumas, Committee Clerk Raymond Gravel, Member (BQ) .................48 committee members. Phone: 613-992-1240 FAX: 613-995-2106 Nina Grewal, Member (CON) .....................32 House of Commons Committees Tom Wappel, Chair (L)................................45 Jim Karygiannis, Member (L)......................41 Directorate Patrick Martin, Vice-Chair (NDP)...............37 Ed Komarnicki, Member (CON) .................36 Phone: 613-992-3150 David Tilson, Vice-Chair (CON).................44 Bill Siksay, Member (NDP).........................33 Sukh Dhaliwal, Member (L)........................32 FAX: 613-996-1962 Blair Wilson, Member (IND).......................33 Carole Lavallée, Member (BQ) ...................48 Senate Committees and Private Glen Pearson, Member (L) ..........................43 ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE Legislation Branch Scott Reid, Member (CON) .........................43 DEVELOPMENT / ENVIRONNEMENT -

Conservative Housing and Construction Caucus Newsletter

Volume 1, Issue 1 CONSERVATIVE HOUSING AND CONSTRUCTION CAUCUS NEWSLETTER A Word from the Chair Welcome to our first balanced, healthy housing and Conservative Housing and construction sector, by dealing Construction Caucus with issues such as affordability, e-newsletter! A big thank you sustainability, and the effective to everyone who was involved provision of social housing for and provided articles for our Canadians. first issue! We have a devoted group of Since our inaugural meeting in Conservative caucus members, October, we have had an and along with the support of extraordinary response from Minister Bergen & Minister key stakeholders, meeting with Kenney, we will continue to work over 10 industry groups, closely with all stakeholders for primarily through a series of the betterment of Canada’s luncheon meetings. Each housing sector. get-together has resulted in robust and passionate Hoping you all have a fantastic discussions, great ideas, and summer, and looking forward to agreement on many common seeing you in the fall! goals. It is of vital importance that we continue to work toward a Inside this issue: The Cost of Housing in Ottawa 1 What has the Caucus been up to? 2 CFAA’s Rental Housing Solution 2 A Message from the Honourable 3 Candice Bergen Budget Submissions 2015 3 Local Housing: Brantford’s Rob Melick 4 Membership List 4 Page 1 CONSERVATIVE HOUSING AND CONSTRUCTION CAUCUS NEWSLETTER What has the Caucus been up to? On October 23rd 2013, the Conservative Housing and and priorities related to the Federal Government. Groups Construction Caucus (CHCC) was launched with strong such as the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association, support from Conservative Members of Parliament. -

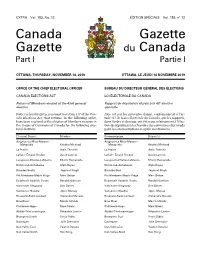

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Core 1..116 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on National Defence NDDN Ï NUMBER 024 Ï 3rd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Wednesday, September 15, 2010 Chair The Honourable Maxime Bernier 1 Standing Committee on National Defence Wednesday, September 15, 2010 Ï (0900) Two and a half years ago, the Government of Canada released the [English] Canada First defence strategy in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In CFDS we committed to rebuilding the Canadian Forces into a first-class The Vice-Chair (Hon. Bryon Wilfert (Richmond Hill, Lib.)): modern military, an integrated, flexible, multi-role, combat-capable Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. This is the Standing military, a military that's able to meet the threats of today and Committee on National Defence, meeting 24. tomorrow. We are at the moment short one minister, the Minister of National Defence, the Honourable Peter MacKay. I understand he was to lead We identified six key missions for our modernized armed forces: off, but we do have two other ministers here, and I'm sure they're conducting daily domestic and continental operations, supporting a quite able to do their presentations. major international event in Canada, responding to a major terrorist attack, supporting civilian authorities during a crisis in Canada, I'm going to make the ground rules clear so we understand what leading or conducting a major international operation for an I'm expecting today. Pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), we are extended period, and deploying forces in response to crises studying the next generation of fighter aircraft. That's what the topic elsewhere in the world for shorter periods. -

Trudeau Government Adjusting to the New Administration Adjusting Tothe New Administration by DEREK ABMA P

TWENTY-EIGHTH YEAR, NO. 1403 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER MONDAY, JANUARY 30, 2017 $5.00 Joe Nancy Sheila Gerry Warren David Michel Jordan Peckford Copps: Nicholls: Kinsella: Drapeau on how where Crane: on the is In Trump’s Trump’s to fi ght Trump are our Canadian the trade America misogyny drains leaders? Forces House swamp tribalism First p. 10 p. 12 p. 9 p. 9 p. 14 p. 15 p. 16 News Trudeau & Trump News Conservative leadership Top job of new Conservative Trudeau government leader to keep progressive, social conservatives united: Tories ‘concerned’ and BY ABBAS RANA conservatives who have been holding their noses for years The next leader of the Conser- and to keep the party united, say vative Party will have to address Conservatives. ‘worried,’ but not frustrations between the social conservatives and progressive Continued on page 18 ‘panicking’ over Trump News Liberal nomination Free Liberal memberships attract administration, say thousands of new members ahead of Ottawa-Vanier nomination BY ABBAS RANA a nomination meeting there, and political insiders the 10 candidates running in this With the incentive of free safe Liberal riding are focused on party membership, Liberal getting as many of these members Trade and security are among the issues Canada has to pay attention Party membership in the riding out as possible on voting day. of Ottawa-Vanier, Ont., has grown to as U.S. President Donald Trump gets started on his agenda. eight times over in anticipation of Continued on page 30 News Lobbying Health most lobbied topic for third straight month BY DEREK ABMA The fi ve topics cited most often in communication reports fi led for Health was the most-lobbied the last month of 2016 were health subject for the third month in with 176 reports, industry with a row in December, according 158, economic development with to the federal lobbyists registry, 141, taxation and fi nance with 123, while topics such as environment and transportation with 121. -

2010-11 Annual Report

2010-11 Parliamentary Interns 2010-11 Annual Report 83rd Annual Conference Canadian Political Science Association Waterloo, Ontario May 18, 2011 Garth Williams Director In Memorium Dr. Jean-Pierre Gaboury passed away on Thursday, March 17, 2011. Jean-Pierre was the longest-serving Director of the Parliamentary Internship Programme, having fulfilled this role on two occasions from 1975-77 and 2002-08. He was the heart and soul of the Programme for many years, a true friend and mentor to all interns, a kind, erudite and honourable man. He cared deeply for the interns and alumni, friends and sponsors, MPs and others whom he brought into the PIP "family." In his last years as Director, Jean-Pierre worked with former interns to update the website and trace alumni through the years, two thoughtful and prescient steps that have laid an important foundation for the years ahead. He is sorely missed. 2 Introduction The 2010-11 intern year has been one of accomplishment and consolidation: building on major initiatives introduced last year by the Programme and our Alumni Association. It has been marked, also, by the energies of a remarkable group of interns (who share some of their experience through blog extracts in the attached Annex I) and, of course, the 2011 Federal Election. These themes run through the following report on Programme activities, budget and governance issues described below. Please note the recommendation of the Advisory Board, for decision by the CPSA Board, on page 8. Programme Activities Intern activities focused on the three fundamental objectives of the Programme: 1. Support democracy by providing qualified assistants to Members of Parliament 2. -

Core 1..52 Committee

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security SECU Ï NUMBER 056 Ï 3rd SESSION Ï 40th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Thursday, February 17, 2011 Chair Mr. Kevin Sorenson 1 Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security Thursday, February 17, 2011 Ï (0850) approximately $620 million a year for additional operating and [English] maintenance and capital expenditures, and $360 million per year or The Chair (Mr. Kevin Sorenson (Crowfoot, CPC)): Good $1.8 billion over five years for new construction. morning, everyone. This is meeting number 56 of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security, of Thursday, The second point is that parliamentarians have not been provided February 17, 2011. with sufficient fiscal transparency to carry out their fiduciary Today we are commencing a study of the expansion of responsibilities with respect to changes in crime legislation. In the penitentiaries. We will hear from the Minister of Public Safety and case of the TSA, parliamentarians were advised by the government from Correctional Services of Canada a little later on this morning, during review of the draft legislation that estimated costs were a but in our first hour we will hear from the Library of Parliament. cabinet confidence. Estimated costs were revealed by the govern- ment only after the draft legislation became law, and the estimate did We welcome Kevin Page, the Parliamentary Budget Officer. He is not include disclosure with respect to methodology and key accompanied by his officials, including Mostafa Askari, assistant assumptions. parliamentary budget officer for economic and fiscal analysis; Sahir Khan, assistant parliamentary budget officer for expenditure and revenue analysis; also, I believe Ashutosh Rajekar, financial advisor, Parliamentarians do not know whether the fiscal planning will be here as well. -

Canada Gazette, Part I, Extra

EXTRA Vol. 149, No. 7 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 149, no 7 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 2015 OTTAWA, LE MARDI 3 NOVEMBRE 2015 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 42nd general election Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 42e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of Com- ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de député(e)s à mons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Député(e)s Saint Boniface—Saint Vital Dan Vandal Saint-Boniface—Saint-Vital Dan Vandal Whitby Celina Whitby Celina Caesar-Chavannes Caesar-Chavannes Davenport Julie Dzerowicz Davenport Julie Dzerowicz Repentigny Monique Pauzé Repentigny Monique Pauzé Salaberry—Suroît Anne Minh-Thu Quach Salaberry—Suroît Anne Minh-Thu Quach Saint-Jean Jean Rioux Saint-Jean Jean Rioux Beloeil—Chambly Matthew Dubé Beloeil—Chambly Matthew Dubé Terrebonne Michel Boudrias Terrebonne Michel Boudrias Châteauguay—Lacolle Brenda Shanahan Châteauguay—Lacolle Brenda Shanahan Ajax Mark Holland Ajax Mark Holland Oshawa Colin Carrie Oshawa -

Graduation Convocation

22nd Graduation Convocation M.vy 9' 7009 CONCORDIAUniversity College of Alberta Welcome and History The Board of Regents, students, faculty, and staff of Concordia University College of Alberta extend a warm welcome to all who join us as we confer degrees upon members of our twenty-second graduating class. We celebrate the achievements of this graduating class and give thanks as they join the growing ranks of Concordia alumni who are serving others with the academic and leadership skills they have attained. This Convocation marks the end of a year of accomplishments and new develop ments in the life of Concordia. Concordia continues to rank near the top in the category of smaller universities in the annual Globe and Mall "Report Card" survey getting A-i-'s and A's in areas such as the quality of teaching,the faculty's interaction with students, and the quality of the overall university experience.This fall, Concordia will begin offering a Master of Arts degree in Biblical and Christian Studies, with areas of concentration in Old and New Testament Studies, and Christian Theology and History, Concordia's role in the educational history of the province began in 1921, when the institution was founded to prepare young men for preaching and teaching ministries in the Lutheran church. In 1939, Concordia expanded to include women and to offer general courses of study and an accredited high school program. In 1967, Concordia began offering first-year university courses in affiliation with the University of Alberta.Today Concordia offers three- and four- year Bachelor of Arts degrees, three- and four-year Bachelor of Science degrees, a four-year Bachelor of Management degree, a Bachelor of Education (After Degree), a Bachelor of Environmental Health (After Degree), a Master's degree In Information Systems Security Management, a Director of Parish Services Program and colloquy programs for the church, as well as extensive professional and continuing education programs. -

DEPLETED URANIUM and CANADIAN VETERANS Report Of

DEPLETED URANIUM AND CANADIAN VETERANS Report of the Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs Greg Kerr Chair JUNE 2013 41st PARLIAMENT, FIRST SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. The House of Commons retains the right and privilege to find users in contempt of Parliament if a reproduction or use is not in accordance with this permission. -

The Fragility of Fear: the Contentious Politics of Emotion and Security in Canada

The Fragility of Fear: the Contentious Politics of Emotion and Security in Canada by Eric Van Rythoven A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2017, Eric Van Rythoven Abstract International Relations (IR) theory commonly holds security arguments as powerful instruments of political mobilization because they work to instill, circulate, and intensify popular fears over a threat to a community. Missing from this view is how security arguments often provoke a much wider range of emotional reactions, many of which frustrate and constrain state officials’ attempts to frame issues as security problems. This dissertation offers a corrective by outlining a theory of the contentious politics of emotion and security. Drawing inspiration from a variety of different social theorists of emotion, including Goffman’s interactionist sociology, this approach treats emotions as emerging from distinctive repertoires of social interaction. These emotions play a key role in enabling audiences to sort through the sound and noise of security discourse by indexing the significance of different events to our bodies. Yet popular emotions are rarely harmonious; they’re socialized and circulated through a myriad of different pathways. Different repertoires of interaction in popular culture, public rituals, and memorialization leave audiences with different ways of feeling about putative threats. The result is mixed and contentious emotions which shape both opportunities and constraints for new security policies. The empirical purchase of this theory is illustrated with two cases drawn from the Canadian context: indigenous protest and the F-35 procurement.