Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vegetation Map of the Valles Caldera National Preserve, New

______________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of the Valles Caldera National Preserve, New Mexico ______________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of Valles Caldera National Preserve, New Mexico 1 Esteban Muldavin, Paul Neville, Charlie Jackson, and Teri Neville2 2006 ______________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY To support the management and sustainability of the ecosystems of the Valles Caldera National Preserve (VCNP), a map of current vegetation was developed. The map was based on aerial photography from 2000 and Landsat satellite imagery from 1999 and 2001, and was designed to serve natural resources management planning activities at an operational scale of 1:24,000. There are 20 map units distributed among forest, shrubland, grassland, and wetland ecosystems. Each map unit is defined in terms of a vegetation classification that was developed for the preserve based on 348 ground plots. An annotated legend is provided with details of vegetation composition, environment, and distribution of each unit in the preserve. Map sheets at 1:32,000 scale were produced, and a stand-alone geographic information system was constructed to house the digital version of the map. In addition, all supporting field data was compiled into a relational database for use by preserve managers. Cerro La Jarra in Valle Grande of the Valles Caldera National Preserve (Photo: E. Muldavin) 1 Final report submitted in April 4, 2006 in partial fulfillment of National Prak Service Award No. 1443-CA-1248- 01-001 and Valles Caldrea Trust Contract No. VCT-TO 0401. 2 Esteban Muldavin (Senior Ecologist), Charlie Jackson (Mapping Specialist), and Teri Neville (GIS Specialist) are with Natural Heritage New Mexico of the Museum of Southwestern Biology at the University of New Mexico (UNM); Paul Neville is with the Earth Data Analysis Center (EDAC) at UNM. -

The National Park System

January 2009 Parks and Recreation in the United States The National Park System Margaret Walls BACKGROUNDER 1616 P St. NW Washington, DC 20036 202-328-5000 www.rff.org Resources for the Future Walls Parks and Recreation in the United States: The National Park System Margaret Walls∗ Introduction The National Park Service, a bureau within the U.S. Department of the Interior, is responsible for managing 391 sites—including national monuments, national recreation areas, national rivers, national parks, various types of historic sites, and other categories of protected lands—that cover 84 million acres. Some of the sites, such as Yellowstone National Park and the Grand Canyon, are viewed as iconic symbols of America. But the National Park Service also manages a number of small historical sites, military parks, scenic parkways, the National Mall in Washington, DC, and a variety of other protected locations. In this backgrounder, we provide a brief history of the Park Service, show trends in land acreage managed by the bureau and visitation at National Park Service sites over time, show funding trends, and present the challenges and issues facing the Park Service today. History National parks were created before there was a National Park Service. President Ulysses S. Grant first set aside land for a “public park” in 1872 with the founding of Yellowstone. Yosemite, General Grant (now part of Kings Canyon), and Sequoia National Parks in California were created in 1890, and nine years later Mount Rainier National Park was set aside in Washington. With passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906, the President was granted authority to declare historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and sites of scientific interest as national monuments. -

417 US National Parks, Historical Sites, Preserves, Seashores and More!

417 US National Parks, Historical Sites, Preserves, Seashores and more! Alabama o Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument o Freedom Riders National Monument o Horseshoe Bend National Military Park o Little River Canyon National Preserve o Russell Cave National Monument o Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site o Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site Alaska o Alagnak Wild River o Aniakchak National Monument o Aniakchak National Preserve o Bering Land Bridge National Preserve o Cape Krusenstern National Monument o Denali National Park o Denali National Preserve o Gates of the Arctic National Park o Gates of the Arctic National Preserve o Glacier Bay National Park o Glacier Bay National Preserve o Katmai National Park o Katmai National Preserve o Kenai Fjords National Park o Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (also Washington) o Kobuk Valley National Park o Lake Clark National Park o Lake Clark National Preserve o Noatak National Preserve o Sitka National Historical Park o World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument (also California, Hawaii) o Wrangell-St. Elias National Park o Wrangell-St. Elias National Preserve o Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Courtesy of ParkRangerJohn.com Arizona o Canyon De Chelly National Monument o Casa Grande Ruins National Monument o Chiricahua National Monument o Coronado National Memorial o Fort Bowie National Historic Site o Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (also Utah) o Grand Canyon National Park o Hohokam Pima National Monument o Hubbel Trading Post National Historic Site -

Mojave National Preserve California

A fact sheet from 2017 Dougall Photography/iStockphoto Mojave’s $131.8 million maintenance backlog includes repairs to historic buildings such as the Kelso Depot. Shane McMurphy/iStockphoto Mojave National Preserve California Overview Two hours from the hustle and bustle of Las Vegas and 100 miles from the nearest lodging lies California’s Mojave National Preserve. The Las Vegas Review-Journal dubbed this vast desert in San Bernardino County the “perfect escape for those seeking serenity.” The preserve spans 1.6 million acres, making it the third-largest National Park Service (NPS) unit in the contiguous United States. Mojave is ecologically and geologically diverse, with towering sand dunes, dun-colored mesas, and volcanic formations providing habitat for its abundant plants and wildlife. In addition to the densest forest of Joshua trees in the world, visitors can see bighorn sheep, bobcats, golden eagles, and breathtaking displays of seasonal wildflowers. The preserve also has a rich cultural heritage. Lands first inhabited by the Chemehuevi and Mojave tribes attracted gold miners in the late 19th century and were later crossed by several railroad lines. Visitors can learn more about this history through exhibits at the visitor center and by exploring archaeological sites, abandoned mines, and preserved homesteads and other buildings. The ghost town of Kelso, which once served as a Union Pacific Railroad depot and mining outpost, is one of the park’s most popular destinations. Unfortunately, Mojave faces over $131 million in deferred maintenance. Maintenance challenges Nearly all of Mojave’s needed repairs are for its road network. Severe deterioration of some sections of pavement has prompted the NPS to warn visitors of dangerous potholes. -

Land Cover Mapping of the National Park Service Northwest Alaska Management Area Using Landsat Multispectral and Thematic Mapper Satellite Data

Land Cover Mapping of the National Park Service Northwest Alaska Management Area Using Landsat Multispectral and Thematic Mapper Satellite Data By Carl J. Markon and Sara Wesser Open-File Report 00-51 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey LAND COVER MAPPING OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NORTHWEST ALASKA MANAGEMENT AREA USING LANDSAT MULTISPECTRAL AND THEMATIC MAPPER SATELLITE DATA By Carl J. Markon1 and Sara Wesser2 1 Raytheon SIX Corp., USGS EROS Alaska Field Office, 4230 University Drive, Anchorage, AK 99508-4664. E-mail: [email protected]. Work conducted under contract #1434-CR-97-40274 2National Park Service, 2525 Gambell St., Anchorage, AK 99503-2892 Land Cover Mapping of the National Park Service Northwest Alaska Management Area Using Landsat Multispectral Scanner and Thematic Mapper Satellite Data ABSTRACT A land cover map of the National Park Service northwest Alaska management area was produced using digitally processed Landsat data. These and other environmental data were incorporated into a geographic information system to provide baseline information about the nature and extent of resources present in this northwest Alaskan environment. This report details the methodology, depicts vegetation profiles of the surrounding landscape, and describes the different vegetation types mapped. Portions of nine Landsat satellite (multispectral scanner and thematic mapper) scenes were used to produce a land cover map of the Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Noatak National Preserve and to update an existing land cover map of Kobuk Valley National Park Valley National Park. A Bayesian multivariate classifier was applied to the multispectral data sets, followed by the application of ancillary data (elevation, slope, aspect, soils, watersheds, and geology) to enhance the spectral separation of classes into more meaningful vegetation types. -

Climate Change and Florida's National Parks

Climate Change and Florida’s National Parks Florida is among the most climate change-threatened states in the United States. Florida’s treasured national parks—spanning the Greater Everglades ecosystem northward into Gulf Islands National Seashore and beyond—are being impacted by our changing climate. Climate change is the greatest threat science-based policies that enhance the Florida’s economy. NPCA’s Sun Coast America’s national parks have ever faced. resilience of our incredible system of region is systematically assessing, through Nearly everything we know and love about national parks. With Florida’s low elevation, research and analysis, the most serious the parks—their plants and animals, rivers national park sites in the state are especially climate impacts threatening national and lakes, beaches, historic structures, susceptible to the threats associated with park landscapes. This regional climate and more—is already under stress from climate change. Sea level rise, changing dispatch thus serves a twofold purpose: to our changing climate. As America’s ocean conditions, and shifting weather shine a light on climate case studies across leading voice for our national parks, patterns are impacting our landscapes. iconic Floridian places, and to share what National Parks Conservation Association All of these climate impacts converge to NPCA’s Sun Coast team is doing to help (NPCA) is at the forefront of efforts to present unprecedented challenges to park address and adapt to climate threats to address climate impacts and promote management, preservation, tourism, and our treasured national park ecosystems. Above: Florida Bay in Everglades National Park ©South Florida Water Management District NATIONAL PARK Rising Sea Levels Threaten THREAT Biodiversity & Cultural Resources While all national park units in Florida Importance, Everglades National Park are threatened by sea level rise, some protects an abundance of biodiversity parks are more vulnerable than others. -

Water Quality in Big Cypress National Preserve and Everglades National Park—Trends and Spatial Characteristics of Selected Constituents

Water Quality in Big Cypress National Preserve and Everglades National Park—Trends and Spatial Characteristics of Selected Constituents By Ronald L. Miller, U.S. Geological Survey, St. Petersburg, Florida; Benjamin F. McPherson, U.S. Geological Survey, Tampa, Florida; and Robert Sobczak, and Christine Clark, Big Cypress National Preserve, Ochopee, Florida Water Resources Investigations Report 03-4249 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virgina: 2004 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to repro- duce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. iii Contents Abstract. 1 Introduction . 2 Data Sources . 4 Objective and Scope . 4 Data Analysis . 4 Problems in Long-Term Trend Analyses. 5 Statistics . 5 Trends in Rainfall, Water Levels, and Flows . 6 Water Quality in South Florida . 8 Water Quality Changes Over Time. 9 Eastern Everglades . 9 Taylor Slough Bridge. 9 Shark River Slough. 11 Western Everglades and Big Cypress Swamp . 11 Site P-34 . 15 Bridge 105 Site. 15 Spatial Patterns in Water Quality . 18 Park Boundary Water-Quality Conditions . -

Big Thicket Bulletin, Issue

BIG THICKET BULLETIN April . May . June 2015 Issue #126 BIG THICKET SCIENCE CONFERENCE ATBI slime mold researcher Plenary speaker Dr. Kirk Winemiller Tonkawa Sand Hills trip leader Plenary speaker Julie Shackleford Katie Winsett Dr. James Van Kley (front lef) checking his species list. Te 2015 Big Ticket Science Conference: Biodiversity Live music was provided by the Sawmill Vagrants from and Ecology of the West Gulf Coastal Plain Landscape Kennard, Texas. On Saturday research presentations was hosted at Stephen F. Austin University’s Student were given in a concurrent session format. Results of Center in Nacogdoches, April 17-19. Afer a welcome 33 ecologic and management studies were presented by the Conference hosts, two Plenary speakers led of Saturday morning and afernoon. Tese included one by the conference on Friday morning. Julie Shackleford of Big Ticket National Preserve ATBI slime mold researcher, Te Conservation Fund presented an overview of Te Katie Winsett, a Lecturer in the Environmental Studies Conservation Fund’s mission in East Texas and provided Program at North Carolina State University. an update of recent land acquisitions made by the Fund. A choice of three feld trips was ofered on Sunday. Dr. Dr. Kirk Wine-miller, a Regents Professor in Texas A&M’s James Van Kley led a trip to the Tonkawa Sandhills Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, presented a talk north of Nacogdoches where natural springs and sandy based on his ecological research. soils derived from the 45+ million-year-old beach sands A poster session followed with 21 posters on a variety of the Carrizo Sand formation provide both moist and of research topics conducted across the Western Coastal dry habitats for unique foras. -

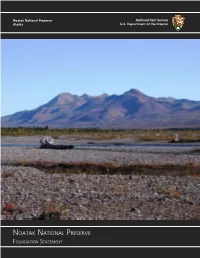

Noatak National Preserve Foundation Statement 2009

Noatak National Preserve National Park Service Alaska U.S. Department of the Interior NOATAK NATIONAL PRESERVE FOUNDATION STATEMENT This page left intentionally blank. Noatak National Preserve Foundation Statement July, 2009 Prepared By: Western Arctic National Parklands National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office National Park Service, Denver Service Center This page left intentionally blank. Table of Contents Noatak National Preserve – Foundation Statement Elements of a Foundation Statement…2 Establishment of Alaska National Parks…3 Summary Purpose Statement…4 Significance Statements…4 Location Regional Map…5 Purpose Statement…6 Significance Statements / Fundamental Resources and Values / Interpretive Themes 1. Arctic-Subarctic River Basin Ecosystem…7 2. Scientific Research...8 3. Subsistence …9 4. Arctic Wilderness…10 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments…11 Workshop Participants…12 Appendix A - Legislation Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act – Selected Excerpts …14 Appendix B – Legislative History Proclamation 4624 – Noatak National Monument, 1978…24 Elements of a Foundation Statement The Foundation Statement is a formal description of Noatak National Preserve’s (preserve) core mission. It is a foundation to support planning and management of the preserve. The foundation is grounded in the preserve’s legislation and from knowledge acquired since the preserve was originally established. It provides a shared understanding of what is most important about the preserve. This Foundation Statement describes the preserve’s -

Public Law 106–530 106Th Congress An

PUBLIC LAW 106–530—NOV. 22, 2000 114 STAT. 2527 Public Law 106–530 106th Congress An Act To provide for the establishment of the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve and the Baca National Wildlife Refuge in the State of Colorado, and Nov. 22, 2000 for other purposes. [S. 2547] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Great Sand Dunes National SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. Park and Preserve Act of This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Great Sand Dunes National 2000. Park and Preserve Act of 2000’’. 16 USC 410hhh note. SEC. 2. FINDINGS. 16 USC 410hhh. Congress finds that— (1) the Great Sand Dunes National Monument in the State of Colorado was established by Presidential proclamation in 1932 to preserve Federal land containing spectacular and unique sand dunes and additional features of scenic, scientific, and educational interest for the benefit and enjoyment of future generations; (2) the Great Sand Dunes, together with the associated sand sheet and adjacent wetland and upland, contain a variety of rare ecological, geological, paleontological, archaeological, scenic, historical, and wildlife components, which— (A) include the unique pulse flow characteristics of Sand Creek and Medano Creek that are integral to the existence of the dunes system; (B) interact to sustain the unique Great Sand Dunes system beyond the boundaries of the existing National Monument; (C) are enhanced by the serenity and rural western setting of the area; and (D) comprise a setting of irreplaceable -

Mojave National Preserve

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Enjoy the View – Visual Resources Inventory Inventory Report Mojave National Preserve Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJA/NRR—2016/1322 ON THE COVER Photograph of View of Ivanpah Valley from Morning Star Mine Photograph courtesy of NPS Enjoy the View – Visual Resources Inventory Report Mojave National Preserve Natural Resource Report NPS/MOJA/NRR–2016/1322 Mark Meyer National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science – Air Resources Division Lakewood, CO 80235 Debra Hughson National Park Service Mojave National Preserve Barstow, CA 92311 October 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Denver, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Oregon Caves Draft Preserve Management Plan

OREGON CAVES NATIONAL MONUMENT AND PRESERVE Preserve Management Plan Oregion Caves National Monument and Preserve 19000 Caves Hwy Cave Junction, OR 97523 Contact: Vicki Snitzler, Superintendent Prepared by: National Park Service Pacific West Region—San Francisco Office Park Planning and Environmental Compliance 333 Bust St. #500 San Francisco, CA 94104 Please refer to “How to Use This Document” to navigate through the chapters. To comment on this document, please refer to “How to Comment on This Document.” These sections can be found on the following pages. Marshall’s Gooseberry, a regional endemic near Bigelow Lakes. Photo: NPS. LETTER FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT Greetings! Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve is inviting public comment on the management plan and environmental assessment for the recently designated national preserve, as well as a wild and scenic river study. The legislation that created the 4,070 acre preserve was signed into law on December 19, 2014. This plan addresses management of roads, trails, commercial activities, hunting, hiking, use of pack animals, and backcountry camping, among other things. The preserve contains a campground, nearly 20 miles of gravel roads and 17 miles of trails. There is a federally listed endangered species (spotted owl) and a species of concern (fisher). The area contains a number of rare plants as well as areas that have Port Orford Cedar root rot disease which will need to be kept contained. The preserve planning process is happening at the same time as the wild and scenic river study authorized in the December 2014 legislation. The study examines whether five creek segments on the monument and preserve should be included in the national wild and scenic rivers system.