Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve Project Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential Spray Drift Damage: What Steps to Take?

[email protected] • (479) 575-7646 www.nationalaglawcenter.org An Agricultural Law Research Publication Potential Spray Drift Damage: What Steps to Take? by Tiffany Dowell Lashmet Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service This material is based upon work supported by the National Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. An Agricultural & Food Law Consortium Project Potential Spray Drift Damage: What Steps to Take? Tiffany Dowell Lashmet Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service As many farmers know all too well, applications of various pesticides can result in drift and cause damage to neighboring property owners. In recent years, incidences of spray drift damage have been frequent and well-publicized. In the event a farmer discovers damage to his or her own crop, it is important for the injured producer to know some steps to take. Document, Document, Document First and foremost, any farmer who suspects possible injury from drift should document all potential evidence, including taking photographs or samples of damaged crops or foliage, keeping a log of spray applications made by neighboring landowners, noting any custom applicators applying pesticide in the area, documenting environmental conditions like wind speed, direction, and temperatures, and getting statements from any witnesses who might have seen recent pesticide applications. Photographs should be taken continually for several days, as the full extent of damage may not occur for several weeks after application. The more documentation a landowner has, the better his chances of recovery will be; whether it is from the offender, the offender’s insurance or potentially even the injured party’s insurance. -

Bwsr Featured Plant Minnesota's Milkweeds

BWSR FEATURED PLANT MINNESOTA’S MILKWEEDS Publication Date: 6‐1‐13 Milkweeds play a key role in wetlands, prairies, savannas and forests in Minnesota. The genus (Asclepias) is particularly important as a nectar and larval food source for a wide range of insect species. The best known example is the monarch butterfly whose larvae appear to feed only on milkweeds. Milkweeds have a unique pollination mechanism where pollen grains are enclosed in waxy sacs called “pollina” that attach to the legs of butterflies, moths, bees, ants and wasps and are then deposited in another milkweed flower if they step into a specialized anther opening. Most milkweeds are toxic to vertebrate herbivores due to cardiac glycosides that are in their plant cells. In addition to supporting insect populations, Butterfly Milkweed milkweeds also provide other landscape benefits due to their extensive root systems (sometimes deep roots, sometimes horizontal) that Photos by Dave Hanson decrease compaction, add organic material to the soil and improve unless otherwise stated water infiltration. Common milkweed is probably the best known milkweed species as it is found in all counties of the state and was included on some county prohibited noxious weed lists. The species was considered a common agricultural weed as its extensive root network made it difficult to remove from agricultural fields with cultivators. Now the species is effectively removed from genetically modified corn and soybean fields that are sprayed with herbicide. This practice has contributed to significant declines in milkweed species, with an estimated 58% decline in the Midwest between 1999 and 2010 and a corresponding 81% decline in monarch butterfly production (Pleasants & Oberhauser, 2013). -

Elements by Townrange for Racine County

Elements by Townrange for Racine County The Natural Heritage Inventory (NHI) database contains recent and historic element (rare species and natural community) observations. A generalized version of the NHI database is provided below as a general reference and should not be used as a substitute for a WI Dept of Natural Resources NHI review of a specific project area. The NHI database is dynamic, records are continually being added and/or updated. The following data are current as of 03/26/2014: Town Range State Federal State Global Group Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Rank Rank Name Agalinis auriculata Earleaf Foxglove SC S1 G3 Plant Asclepias lanuginosa Woolly Milkweed THR S1 G4? Plant Asclepias purpurascens Purple Milkweed END S3 G5? Plant Asclepias sullivantii Prairie Milkweed THR S2S3 G5 Plant Carex garberi Elk Sedge THR S2 G5 Plant~ Carex swanii Swan Sedge SC S1 G5 Plant Cypripedium candidum Small White Lady's-slipper THR S3 G4 Plant~ Dryopteris clintoniana Clinton's Woodfern SC SH G5 Plant Lespedeza leptostachya Prairie Bush-clover END LT S2 G3 Plant Phegopteris hexagonoptera Broad Beech Fern SC S2 G5 Plant Plantago cordata Heart-leaved Plantain END S1 G4 Plant~ Prenanthes aspera Rough Rattlesnake-root END S1 G4? Plant Ranunculus cymbalaria Seaside Crowfoot THR S2 G5 Plant~ Thamnophis proximus Western Ribbonsnake END S1 G5 Snake~ Thamnophis sauritus Eastern Ribbonsnake END S1 G5 Snake~ 001N019E Moxostoma carinatum River Redhorse THR S2 G4 Fish~ 001N020E Moxostoma carinatum River Redhorse THR S2 G4 Fish~ 001N022E Aphredoderus -

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas

Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas Texas milkweed (Asclepias texana), courtesy Bill Carr Compiled by Jason Singhurst and Ben Hutchins [email protected] [email protected] Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas and Walter C. Holmes [email protected] Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas Identification of Milkweeds (Asclepias, Family Apocynaceae) in Texas Created in partnership with the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Design and layout by Elishea Smith Compiled by Jason Singhurst and Ben Hutchins [email protected] [email protected] Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas and Walter C. Holmes [email protected] Department of Biology Baylor University Waco, Texas Introduction This document has been produced to serve as a quick guide to the identification of milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) in Texas. For the species listed in Table 1 below, basic information such as range (in this case county distribution), habitat, and key identification characteristics accompany a photograph of each species. This information comes from a variety of sources that includes the Manual of the Vascular Flora of Texas, Biota of North America Project, knowledge of the authors, and various other publications (cited in the text). All photographs are used with permission and are fully credited to the copyright holder and/or originator. Other items, but in particular scientific publications, traditionally do not require permissions, but only citations to the author(s) if used for scientific and/or nonprofit purposes. Names, both common and scientific, follow those in USDA NRCS (2015). When identifying milkweeds in the field, attention should be focused on the distinguishing characteristics listed for each species. -

Utilizing Novel Grasslands for the Conservation and Restoration Of

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2014 Utilizing novel grasslands for the conservation and restoration of butterflies nda other pollinators in agricultural ecosystems John Thomas Delaney Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons Recommended Citation Delaney, John Thomas, "Utilizing novel grasslands for the conservation and restoration of butterflies and other pollinators in agricultural ecosystems" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 14097. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/14097 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Utilizing novel grasslands for the conservation and restoration of butterflies and other pollinators in agricultural ecosystems by John Thomas Delaney A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Program of Study Committee: Diane M. Debinski, Major Professor David M. Engle Mary A. Harris Amy L. Toth Brian J. Wilsey Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2014 Copyright © John Thomas Delaney, 2014. All rights reserved. ii Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to all of my family, friends, and mentors who have helped me along in this journey. -

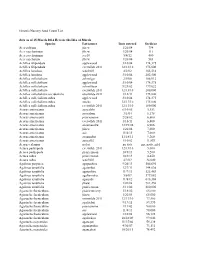

Q Seed Counts

Genesis Nursery Seed Count List data as of 15 March 2014 Beware ths Ides of March Species Lot/source Date entered Seeds/oz Acer rubrum jfnew 1/26/04 794 Acer saccharinum jfnew 1/26/04 111 Acer saccharinum aes10 5/4/12 400 Acer saccharum jfnew 1/26/04 563 Achillea filipendula applewood 3/10/04 174,375 Achillea filipendula everwilde 2011 12/13/10 175,000 Achillea lanulosa wns2001 4/2/02 165,516 Achillea lanulosa applewood 3/10/04 202,500 Achillea millefoilium achmilgo 2/9/06 166,912 Achillea millefoilium applewood 3/10/04 174,375 Achillea millefoilium achmil0san 9/21/02 179,022 Achillea millefoilium everwilde 2011 12/13/10 200,000 Achillea millefoilium occidentalis everwilde 2011 1/16/11 175,000 Achillea millefoilium rubra applewood 3/10/04 174,375 Achillea millefoilium rubra stocks 12/13/10 175,000 Achillea millefoilium rubra everwilde 2011 12/13/10 180,000 Acorus americanus acocalshi 6/10/05 5,553 Acorus americanus acocalsan 3/1/04 6,175 Acorus americanus prairiemoon 2/26/02 6,600 Acorus americanus everwilde 2011 1/16/11 6,800 Acorus americanus acoameroku 12/19/06 6,906 Acorus americanus jfnew 1/26/04 7,000 Acorus americanus aes 11/4/11 7,000 Acorus americanus acoamebat 11/18/11 9,260 Acorus americanus acocal02 1/10/02 11,853 Acorus calamus no lot no date zip, nada, zilch Actaea pachypoda everwilde 2011 12/13/10 5,000 Actaea pachypoda prairiemoon 10/3/13 5,200 Actaea rubra prairiemoon 10/3/13 4,450 Actaea rubra wns2001 4/2/02 34,000 Agalinus purpurea agapuuhiru 9/26/13 506,696 Agalinus tenuifolia agatenbat 12/7/11 144,036 Agalinus tenuifolia -

Amorpha Canescens Pursh Leadplant

leadplant, Page 1 Amorpha canescens Pursh leadplant State Distribution Best Survey Period Photo by Susan R. Crispin Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Status: State special concern the Mississippi valley through Arkansas to Texas and in the western Great Plains from Montana south Global and state rank: G5/S3 through Wyoming and Colorado to New Mexico. It is considered rare in Arkansas and Wyoming and is known Other common names: lead-plant, downy indigobush only from historical records in Montana and Ontario (NatureServe 2006). Family: Fabaceae (pea family); also known as the Leguminosae. State distribution: Of Michigan’s more than 50 occurrences of this prairie species, the vast majority of Synonym: Amorpha brachycarpa E.J. Palmer sites are concentrated in southwest Lower Michigan, with Kalamazoo, St. Joseph, and Cass counties alone Taxonomy: The Fabaceae is divided into three well accounting for more than 40 of these records. Single known and distinct subfamilies, the Mimosoideae, outlying occurrences have been documented in the Caesalpinioideae, and Papilionoideae, which are last two decades from prairie remnants in Oakland and frequently recognized at the rank of family (the Livingston counties in southeast Michigan. Mimosaceae, Caesalpiniaceae, and Papilionaceae or Fabaceae, respectively). Of the three subfamilies, Recognition: Leadplant is an erect, simple to sparsely Amorpha is placed within the Papilionoideae (Voss branching shrub ranging up to ca. 1 m in height, 1985). Sparsely hairy plants of leadplant with greener characterized by its pale to grayish color derived from leaves have been segregated variously as A. canescens a close pubescence of whitish hairs that cover the plant var. -

Vegetative Growth and Organogenesis 555

Vegetative Growth 19 and Organogenesis lthough embryogenesis and seedling establishment play criti- A cal roles in establishing the basic polarity and growth axes of the plant, many other aspects of plant form reflect developmental processes that occur after seedling establishment. For most plants, shoot architecture depends critically on the regulated production of determinate lateral organs, such as leaves, as well as the regulated formation and outgrowth of indeterminate branch systems. Root systems, though typically hidden from view, have comparable levels of complexity that result from the regulated formation and out- growth of indeterminate lateral roots (see Chapter 18). In addition, secondary growth is the defining feature of the vegetative growth of woody perennials, providing the structural support that enables trees to attain great heights. In this chapter we will consider the molecular mechanisms that underpin these growth patterns. Like embryogenesis, vegetative organogenesis and secondary growth rely on local differences in the interactions and regulatory feedback among hormones, which trigger complex programs of gene expres- sion that drive specific aspects of organ development. Leaf Development Morphologically, the leaf is the most variable of all the plant organs. The collective term for any type of leaf on a plant, including struc- tures that evolved from leaves, is phyllome. Phyllomes include the photosynthetic foliage leaves (what we usually mean by “leaves”), protective bud scales, bracts (leaves associated with inflorescences, or flowers), and floral organs. In angiosperms, the main part of the foliage leaf is expanded into a flattened structure, the blade, or lamina. The appearance of a flat lamina in seed plants in the middle to late Devonian was a key event in leaf evolution. -

Hophornbeam Copperleaf

Extension W120 Hophornbeam Copperleaf Larry Steckel, Assistant Professor, Plant Sciences Hophornbeam Copperleaf Acalypha ostryifolia Riddell. Also known as pineland three-seeded mercury. Classifi cation and Description Hophornbeam (H) copperleaf is a member of the Euphorbiaceae or spurge family. H copperleaf has a very characteristic heart-shaped serrated leaf. The other cop- perleaf species in Tennessee, Virginia copperleaf, does not have serrations on the leaves. H copperleaf can grow to heights of 1 to 4 feet. Its leaves are alternate; blades simple. Tennessee producers sometimes misidentify it as a pig- weed. The reason for this mistake is that H copperleaf has a similar emergence pattern as pigweed. In addition, it is very tolerant to ALS-inhibiting herbicides such as Envoke®, Classic® and Steadfast®, which is also consistent with the pigweed species Palmer amaranth. H copperleaf typically emerges from June to September and reproduces by seeds Late-emerging copperleaf in cotton numbering as high as 12,500 seeds per plant, according to a Kansas study. The male owers of H copperleaf are found on auxillary spikes, while the female owers are on a long terminal spike. Historical H copperleaf is native to Tennessee and can be found throughout the state in agronomic crops, pastures, or- chards, roadsides and waste areas. H copperleaf was not a major problem in Tennessee agronomic crops until early this decade. The advent of no-till row crop production along with Roundup Ready® crops has become a good niche environment for this weed. The reduction in the use of cultivation and applications of soil-applied residual her- bicides has helped this weed become more established in Tennessee. -

Open Myers THESIS.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Science, Engineering, and Technology IMPACT OF OZONE ON MILKWEED (ASCLEPIAS) SPECIES A Thesis in Environmental Pollution Control by Abigail C. Myers 2016 Abigail C. Myers Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2016 The thesis of Abigail C. Myers was reviewed and approved* by the following: Dennis R. Decoteau Professor of Horticulture and Plant Ecosystem Health Thesis Advisor Donald D. Davis Professor of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology Richard Marini Professor of Horticulture Shirley Clark Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering Graduate Program Coordinator, Environmental Engineering and Environmental Pollution Control *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Tropospheric (or ground level) ozone in ambient concentrations can damage vegetation and interfere with the human respiratory system. Plants as bioindicators of ozone are commonly used to detect phytotoxic levels of tropospheric ozone where physical/chemical/electrical monitoring equipment cannot be utilized due to expense, electrical needs, or availability of instruments. Asclepias syriaca (Common Milkweed) has been effectively used as a bioindicator for ozone. Visual ozone injury on Common Milkweed is characterized as purple stippling of the upper surface of older leaves as the season progresses, the purple coloration of the upper leaf surface may encompass most of the leaf surface. While sensitivity to ozone has been documented on Common Milkweed, less is known about the ozone sensitivity of other Asclepias species and little is known regarding the concentration dose response of Common Milkweed to ozone and timing of visual symptoms. Of the Asclepias species evaluated Tropical Milkweed (A. -

Grasses of the Texas Hill Country: Vegetative Key and Descriptions

Hagenbuch, K.W. and D.E. Lemke. 2015. Grasses of the Texas Hill Country: Vegetative key and descriptions. Phytoneuron 2015-4: 1–93. Published 7 January 2015. ISSN 2153 733X GRASSES OF THE TEXAS HILL COUNTRY: VEGETATIVE KEY AND DESCRIPTIONS KARL W. HAGENBUCH Department of Biological Sciences San Antonio College 1300 San Pedro Avenue San Antonio, Texas 78212-4299 [email protected] DAVID E. LEMKE Department of Biology Texas State University 601 University Drive San Marcos, Texas 78666-4684 [email protected] ABSTRACT A key and a set of descriptions, based solely on vegetative characteristics, is provided for the identification of 66 genera and 160 grass species, both native and naturalized, of the Texas Hill Country. The principal characters used (features of longevity, growth form, roots, rhizomes and stolons, culms, leaf sheaths, collars, auricles, ligules, leaf blades, vernation, vestiture, and habitat) are discussed and illustrated. This treatment should prove useful at times when reproductive material is not available. Because of its size and variation in environmental conditions, Texas provides habitat for well over 700 species of grasses (Shaw 2012). For identification purposes, the works of Correll and Johnston (1970); Gould (1975) and, more recently, Shaw (2012) treat Texas grasses in their entirety. In addition to these comprehensive works, regional taxonomic treatments have been done for the grasses of the Cross Timbers and Prairies (Hignight et al. 1988), the South Texas Brush Country (Lonard 1993; Everitt et al. 2011), the Gulf Prairies and Marshes (Hatch et al. 1999), and the Trans-Pecos (Powell 1994) natural regions. In these, as well as in numerous other manuals and keys, accurate identification of grass species depends on the availability of reproductive material.