Syrian Arab Republic, Map No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

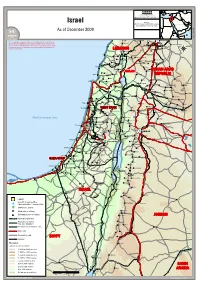

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

Irbid Development Area

Where to Invest? Jordan’s Enabling Platforms Elias Farraj Advisor to the CEO Jordan Investment Board Enabling Platforms A. Development Areas and Zones . King Hussein Business Park (KHBP) . King Hussein Bin Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) . Irbid Development Area . Ma’an Development Area (MDA) B. Aqaba Special Economic Zone C. Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) D. Industrial Estates E. Free Zones Development Area Law • The Government of Jordan Under the Development Areas Law (GOJ) enacted new Income Tax[1] 5% On all taxable income from Development Areas Law in activities within the Area 2008 that provides a clear Sales Tax 0% On goods sold into (or indicator of the within) the Development Area for use in economic Government’s commitment activities to the success of Import Duties 0% On all materials, instruments, development zones. machines, etc to be used in establishing, constructing and equipping an enterprise • This law aims to provides in the Area further streamlining and Social Services Tax 0% On all income accrued within enhance quality-of-service the Area or outside the in the delivery of licensing, Kingdom Dividends Tax 0% On all income accrued within permits and the ongoing the Area or outside the procedures necessary for the Kingdom operations of site manufacturers and 1 No income tax on profits from exports exporters. Areas Under the Development Areas Law Irbid Development King Hussein Bin Area (IDA) Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) ICT, Healthcare Middle & Back Offices, and Research and Industrial Production, Development. -

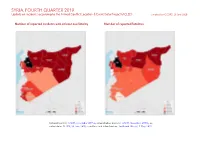

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

1St-Baghdad-International-Water-Conference-Modern-Technologies-CA Lebanon-WO-Videos

th 13th -14 March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE Modern Methods of Remote Data collection in Transboundary Rivers Yarmouk River study case Dr. Chadi Abdallah CNRS-L Lebanon Introduction WATER is a precious natural resource and at the same time complex to manage. 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE 24Font width Times New Roman Font type Take in consider the transparency of the color 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE • Difficulty to acquire in-situ data • Sensitivity in data exchange • Contradiction and gaps in data o Area of the watershed (varies from 6,700 Km2 to 8,378 Km2) o Length of the river (varies from 40 Km to 143 Km) o Flow data (variable, not always clear) • Unavailable major datasets o Long-term accurate precipitation o Flow gauging stations o Springs discharge o Wells extraction o Dams actual retention o Detailed LUC 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE Digital Globe-ESRI- GeoEye (0.5m/2011& CORONA (2m/1966) SPOT (10m/2009) 2019) LUC 1966 CWR estimation LUC 2011& 2020 Landsat 5 to 8 (30m/1982- 2020) MODIS-MOD16 CHIRPS (5Km/1980-2015) 150 images (1Km/2000-2020) 493 images Dams actual retention 255 images Precipitation CWR estimation Evapotranspiration LST, NDVI, ET, SMI 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE Jabal Al Qaly'a Yarmouk River Ash Shaykh .! Raqqad Area: 7,386 Km2 • Quneitra .! Jbab .! Length of Main Tributary from • Sanameyn -

Syria Crisis Situation Update (Issue 38)-UNRWA

3/16/13 Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38)-UNRWA Search Search Home About News Programmes Fields Resources Donate You are here: Home News Emergency Reports Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38) Print Page Email Page Latest News Syria crisis situation update (Issue 38) How you can help Tags: conflict | emergency | refugees | Syria | Yarmouk UNRWA statement Donate $16 on killing of UNRWA 16 March 2013 staff member Damascus, Syria and we could help Syria conflict Regional Overview feed a “messy, violent and family tragic”: interview The unrelenting conflict in Syria continues to exact a heavy toll on civilians – with UNRWA Palestine refugees and Syrians alike. Armed clashes continue throughout Commissioner Syria, particularly in Rif Damascus Governorate, Aleppo, Dera’a and Homs. Related Publications General Filippo With external flight options restricted, Palestine refugees in Syria remain a Grandi particularly vulnerable group who are increasingly unable to cope with the Emergency Appeal socioeconomic and security challenges in Syria. As the armed conflict has 2013 Palestine refugees progressively escalated since the launch of UNRWA’s Syria Crisis Response UNRWA Syria Crisis in greater need as 2013, the number of Palestine refugees in Syria in need of humanitarian Response: January Syria crisis assistance has risen to over 400,000 individuals. The number of Palestine June 2013 escalates, warns refugees from Syria who have fled to Jordan has reached 4,695 individuals UNRWA chief and approximately 32,000 refugees are in Lebanon. Gaza Situation Report, 29 November Japan contributes Syria US$15 million to Hostilities around Damascus claimed the lives of at least 25 Palestine Emergency Appeal UNRWA for refugees during the reporting period, including an UNRWA teacher from progress report 39 Palestine refugees Khan Esheih camp. -

Iranian Forces and Shia Militias in Syria

BICOM Briefing Iranian forces and Shia militias in Syria March 2018 Introduction In Iraq, another country where Iran has implemented its proxy policy, the Iranian On Wednesday, 28 February a US media outlet sponsored militias were not disbanded following reported that Iran was building a new military the defeat of ISIS but are standing as a united base 16 km northwest of the Syrian capital, list in the coming elections and will likely lead Damascus. The report included satellite images key institutions in the country. They are also of warehouses which could store short and protected in law as a permanently mobilised medium-range missiles that intelligence officials force, despite the fact that their leaders take said were capable of reaching any part of Israel. orders from Iran rather than the Government in The base, which is operated by the Iranian Baghdad. With the civil war in Syria far from Revolutionary Guard’s (IRGC) special operations over, Iran will likely seek to implement this “Iraq Quds Force, is similar to one established by model” in Syria in the future. the Iranians near the town of al-Kiswah, 15km southwest of Damascus, which was reportedly The sheer number of moving pieces in Syria targeted by Israeli fighter jets last December. – the regime heading south, Iran seeking to establish military bases, Israel becoming more This news followed a feature in the New York active in preventing the establishment of Shia Times which argued that Iran was “redrawing militias and Russia looking to maintain its the strategic map of the region” and that dozens dominance – are creating a combustible situation of bases in Syria were being operated by Iran with high potential for miscalculation, error and and its Shia militia network. -

Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Chapter IV The Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid and Mafraq – A Socio-Economic Perspective With the beginning of the first quarter of 2011, Syrian refugees poured into Jordan, fleeing the instability of their country in the wake of the Arab Spring. Throughout the two years that followed, their numbers doubled and had a clear impact on the bor- dering governorates, namely Mafraq and Irbid, which share a border with Syria ex- tending some 375 kilometers and which host the largest portion of refugees. Official statistics estimated that at the end of 2013 there were around 600,000 refugees, of whom 170,881 and 124,624 were hosted by the local communities of Mafraq and Ir- bid, respectively. This means that the two governorates are hosting around half of the UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan. The accompanying official financial burden on Jordan, as estimated by some inter- national studies, stood at around US$2.1 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit US$3.2 billion in 2014. This chapter discusses the socio-economic impact of Syrian refugees on the host communities in both governorates. Relevant data has been derived from those studies conducted for the same purpose, in addition to field visits conducted by the research team and interviews conducted with those in charge, local community members and some refugees in these two governorates. 1. Overview of Mafraq and Irbid Governorates It is relevant to give a brief account of the administrative structure, demographics and financial conditions of the two governorates. Mafraq Governorate Mafraq governorate is situated in the north-eastern part of the Kingdom and it borders Iraq (east and north), Syria (north) and Saudi Arabia (south and east). -

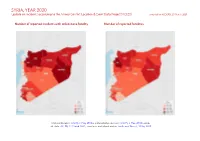

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

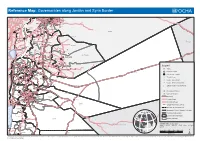

Reference Map: Governorates Along Jordan and Syria Border

Reference Map:] Governorates along Jordan and Syria Border Qudsiya Yafur Tadmor Sabbura Damascus DAMASCUS Obada Nashabiyeh Damascus Maliha Qisa Otayba Yarmuk Zabadin Deir Salman Madamiyet ElshamDarayya Yalda Shabaa Haran Al'awameed Qatana Jdidet Artuz Sbeineh Hteitet Elturkman LEBONAN Artuz Sahnaya Buwayda ] Hosh Sahya Jdidet Elkhas A Tantf DarwashehDarayya Ghizlaniyyeh Khan Elshih Adleiyeh Deir Khabiyeh MqeilibehKisweh Hayajneh Qatana ZahyehTiba Khan Dandun Mazraet Beit Jin Rural Damascus Sa'sa' Hadar Deir Ali Kanaker Duma Khan Arnaba Ghabagheb Jaba Deir Elbakht SYRIA Quneitra Kafr Shams Aqraba Jbab Nabe Elsakher Quneitra As-Sanamayn Hara As-Sanamayn IRAQ Nimer Ankhal Qanniyeh I Jasim Shahba Mahjeh S Nawa Shaqa R Izra' Izra' Shahba Tassil Sheikh Miskine Bisr Elharir A Al Fiq Qarfa Nemreh Abtaa Nahta E Ash-Shajara As-Sweida Da'el Alma Hrak Western Maliha Kherbet Ghazala As-Sweida L Thaala As-Sweida Saham Masad Karak Yadudeh Western Ghariyeh Raha Eastern Ghariyeh Um Walad Bani kinana Kharja Malka Torrah Al'al Mseifra Kafr Shooneh Shamaliyyeh Dar'a Ora Bait Ras Mghayyer Dar'a Hakama ManshiyyehWastiyya Soom Sal Zahar Daraa] Dar'a Tiba Jizeh Irbid Boshra Waqqas Ramtha Nasib Moraba Legend Taibeh Howwarah Qarayya Sammo' Shaikh Hussein Aidoon ! Busra Esh-Sham Arman Dair Abi Sa'id Irbid ] Milh AlRuwaished Salkhad Towns Kofor El-Ma' Nassib Bwaidhah Salkhad Mazar Ash-shamaliCyber City Mghayyer Serhan Mashari'eKora AshrafiyyehBani Obaid ! National Capital Kofor Owan Badiah Ash-Shamaliyya Al_Gharbeh Rwashed Kofor Abiel NULL Ketem ! Jdaitta No'ayymeh -

Downloadpap/Privetrepo/Sitreport.Pdf

Palestinians of Syria Betweenthe Bitterness of Reality and the Hope of Return Palestinians Return Centre Action Group for Palestinians of Syria Palestinians of Syria Between the Bitterness of Reality and the Hope of Return A Documentary Report that Monitors the Development of Events Related to the Palestinians of Syria during January till June2014 Prepared by: Researcher Ibrahim Al Ali Report Planning Introduction......................................................................................................4 The.Field.and.humanitarian.reality.for.Palestinian.camps.and.compounds .in.Syria............................................................................................................7 The.Victims.(January.till.June.014).............................................................4 Civil.work....temporary.alternative................................................................8 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.to.Lebanon..................................................4 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.to.Jordan.....................................................4 Palestinian.refugees.in.Algeria.......................................................................46 Palestinian.Syrian.refugees.in.Libya..............................................................47 Palestinian.refugees.from.Syria.in.Tunisia....................................................49 Palestinian.refugees.in.Turkey.......................................................................5 Refugees.in.the.road.of.Europe......................................................................55 -

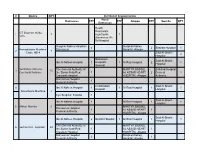

Distribution List in ENG 22 6.Xlsx

# Device QTY Distribution by governorates Rural Damascus QTY QTY Aleppo QTY Sweida QTY Damascus Health Directorate CT Scanner 16/32- 1 1 countryside 1 slice Damascus /Al- Tal Hospital Surgical Kidney Hospital - Surgical Kidney 2 2 Shahba Hospital 1 Hemodialysis Machine Damascus Hospital -Aleppo 2 7 Code: HE-4 Zaid Al-Shariti 2 Hospital Qalamoun Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 Hospitals 1 Al-Razi Hospital 2 1 Hospital General Ventilators Intensive Authority 3 10 The General Authority of MARTYR BASSEL Salkhad Hospital Care Adult Pediatric the Syrian Arab Red 1 AL ASSAD HEART 2 General 1 Crescent Hospital HOSPITAL -Aleppo Authority Damascus Hospital 1 General Authority Al-Zabadani Zaid Al-Shariti 4 Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital Hospital Anesthesia Machine 5 Eye Surgical hospital 1 Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital 5 Mobail Monitor 5 MARTYR BASSEL Damascus Hospital 1 AL ASSAD HEART 1 General Authority HOSPITAL -Aleppo Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 2 Qutaifa Hospital 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital The General Authority of MARTYR BASSEL 6 Suction Unit , Aspirator 10 the Syrian Arab Red 1 AL ASSAD HEART 1 Crescent Hospital HOSPITAL -Aleppo Damascus Hospital Surgical Kidney 2 1 General Authority Hospital -Aleppo Zaid Al-Shariti Ibn Al-Nafees Hospital 1 Qatana Hospital 1 Al-Razi Hospital 1 1 Hospital The General Authority of MARTYR BASSEL the Syrian Arab Red 1 AL ASSAD HEART 1 Shahba Hospital 1 Crescent Hospital HOSPITAL -Aleppo 7 Ultrasonic Nebulizer 10 General