Download Balancing Act: the Australian Greens 2008-2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Submission to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission

Roman Oszanski A Submission to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Preamble I have chosen not to follow the issues papers: their questions are more suited to those planning to expand the nuclear industry, and many of the issues raised are irrelevant if one believes that, based on the evidence, the industry should be left to die a natural death, rather than being supported to the exclusion of more promising technologies. Executive Summary The civil nuclear industry is in decline globally. [Ref charts on existing reactors, rising costs]. It is not an industry of the future, but of the past. If it were not for the intimate connection to the military industry, it would not exist today. There is no economic advantage to SA in expanding the existing industry in this state. Nuclear power does not offer a practical solution to climate change: total lifetime emissions are likely to be (at best) similar to those of gas power plants, and there is insufficient uranium to replace all the goal fired generators. A transition to breeder technologies leaves us with major problems of waste disposal and proliferation of weapons material. Indeed, the problems of weapons proliferation and the black market in fissionable materials mean that we should limit sales of Uranium to countries which are known proliferation risks, or are non- signatories to the NNPT: we should ban sales of Australian Uranium to Russia and India. There is a current oversupply of enrichment facilities, and there is considerable international concern at the possibility of using such facilities to enrich Uranium past reactor grade to weapons grade. -

HON. GIZ WATSON B. 1957

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW WITH HON. GIZ WATSON b. 1957 - STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA - ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION DATE OF INTERVIEW: 2015-2016 INTERVIEWER: ANNE YARDLEY TRANSCRIBER: ANNE YARDLEY DURATION: 19 HOURS REFERENCE NUMBER: OH4275 COPYRIGHT: PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS NOTE TO READER Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Parliament and the State Library are not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge. Bold type face indicates a difference between transcript and recording, as a result of corrections made to the transcript only, usually at the request of the person interviewed. FULL CAPITALS in the text indicate a word or words emphasised by the person interviewed. Square brackets [ ] are used for insertions not in the original tape. ii GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS CONTENTS Contents Pages Introduction 1 Interview - 1 4 - 22 Parents, family life and childhood; migrating from England; school and university studies – Penrhos/ Murdoch University; religion – Quakerism, Buddhism; countryside holidays and early appreciation of Australian environment; Anti-Vietnam marches; civil-rights movements; Activism; civil disobedience; sport; studying environmental science; Albany; studying for a trade. Interview - 2 23 - 38 Environmental issues; Campaign to Save Native Forests; non-violent Direct Action; Quakerism; Alcoa; community support and debate; Cockburn Cement; State Agreement Acts; campaign results; legitimacy of activism; “eco- warriors”; Inaugural speech . -

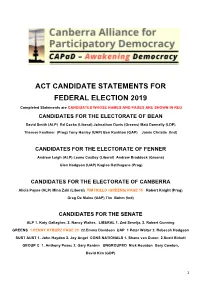

File of Candidate Statements 1

ACTwww.canberra CANDIDATE STATEMENTS-alliance.org.au FOR FEDERAL ELECTION 2019 Completed Statements are CANDIDATES WHOSE NAMES AND PAGES ARE SHOWN IN RED Responses to CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF BEAN [email protected] David Smith (ALP) Ed Cocks (Liberal) Johnathan Davis (Greens) Matt Donnelly (LDP) Enquiries to Bob Douglas Therese Faulkner (Prog) Tony Hanley (UAP) Ben Rushton (GAP) Jamie Christie (Ind)Tel 02 6253 4409 or 0409 233138 CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF FENNER Dear Dr Christie, Andrew Leigh (ALP) Leane Castley (Liberal) Andrew Braddock (Greens) Glen Hodgson (UAP) Kagiso Ratlhagane (Prog) I understand you are a candidate for the forthcoming Federal Election. CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF CANBERRA Congratulations, and best wishes.Alicia Payne (ALP) Mina Zaki (Liberal) TIM HOLLO (GREENS) PAGE 15 Robert Knight (Prog) Greg De Maine (UAP) Tim Bohm (Ind) I am writing on behalf of The Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy (CAPaD), which was formed in 2014, because many CanberransCANDIDATES were FORconcerned THE SENATE at the directions that Australian democracy was taking. ALP 1. Katy Gallagher, 2. Nancy Waites. LIBERAL 1. Zed Seselja, 2. Robert Gunning GREENS 1.PENNY KYBURZ PAGE 23 22.Emma Davidson UAP 1 Peter Walter 2. Rebecah Hodgson CAPaD seeks to enhanceSUST democracy AUST 1. John Haydon 2. Joyin Angel Canberra, CONS NATIONALS 1. Shaneso van Durenthat 2.Scott citizensBirkett can trust their elected GEOUP C 1. Anthony Pesec 2. Gary Kentnn UNGROUPED Nick Houston Gary Cowton, representatives, hold them accountable, engageDavid Kim in (GDP) decision -making, and defend what sustains the public interest. In the lead up to the 2016 ACT Legislative Assembly Elections, the major1 parties were consulted for their views about individual candidate statements, and in the light of those responses, a candidate statement was prepared, which we offered to all registered candidates for lodgement on the CAPaD website. -

Ambassade De France En Australie – Service De Presse Et Information Site : Tél

Online Press review 7 May 2015 The articles in purple are not available online. Please contact the Press and Information Department. FRONT PAGE New Greens leaders seek ‘common ground’ on reform (AUS) Crowe The Greens are promising a fresh look at major budget savings after the sudden installation of Richard Di Natale as the party’s new leader signalled a dramatic shift in power to a new generation but stirred internal rancour. Get over historical indigenous wrongs: Noel Pearson (AUS) Bita Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson has challenged indigenous Australians to get over their traumatic history in the same way that Jews survived the Holocaust. Federal budget 2015: GST on Netflix and more on the way (CAN+SMH) Martin The federal government will move to impose the goods and services tax on services such as Netflix under new rules set to be included in next week's budget. Federal budget 2015: Census saved, $250m investment in Bureau of Statistics (CAN) Martin The census has been saved and the Australian Bureau of Statistics will get a $250 million funding boost as part of the biggest technology upgrade in its 110-year history. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS POLITICS Abbott rejects slur on Paris meeting as Fairfax Media slammed (AUS) Owens Tony Abbott has denied knowing that ambassador Stephen Brady’s male partner had been instructed to leave the tarmac of a Paris airport before the Prime Minister’s arrival on Anzac Day. Smearing Tony Abbott as a homophobe is victory for hatred (AUS/Comment) Kenny Given Tony Abbott has been dubbed a misogynist, Islamophobe and racist, I suppose the - occasional allegation of homophobia shouldn’t be a surprise. -

Senator Bob Brown - Australian Greens

Senator Bob Brown - Australian Greens Bob Brown, born in 1944, was educated in rural New South Wales, became captain of Blacktown Boys High School in Sydney and graduated in medicine from Sydney University in 1968. He became the Director of the Wilderness Society which organised the blockade of the dam-works on Tasmania’s wild Franklin River in 1982/3. Some 1500 people were arrested and 600 jailed, including Bob Brown who spent 19 days in Risdon Prison. On the day of his release, he was elected as the first Green into Tasmania's Parliament. After federal government intervention, the Franklin River was protected in 1983. As a State MP, Bob Brown introduced a wide range of private member's initiatives, including for freedom of information, death with dignity, lowering parliamentary salaries, gay law reform, banning the battery-hen industry and nuclear free Tasmania. Some succeeded, others not. Regrettably, his 1987 bill to ban semi-automatic guns was voted down by both Liberal and Labor members of the House of Assembly, seven years before the Port Arthur massacre. In 1989, he led the parliamentary team of five Greens which held the balance of power with the Field Labor Government. The Greens saved 25 schools from closure, instigated the Local Employment Initiatives which created more than 1000 jobs in depressed areas, doubled the size of Tasmania's Wilderness World Heritage Area to 1.4 million hectares, created the Douglas-Apsley National Park and supported tough fiscal measures to recover from the debts of the previous Liberal regime. Bob resigned from the State Parliament in 1993 and Christine Milne took over as leader of the Tasmanian Greens. -

The Charter and Constitution of the Australian Greens May 2020 Charter

The Charter and Constitution of the Australian Greens May 2020 Charter .......................................................................................................................................................................3 Basis of The Charter ..............................................................................................................................................3 Ecology ..................................................................................................................................................................3 Democracy.............................................................................................................................................................3 Social Justice .........................................................................................................................................................3 Peace ....................................................................................................................................................................3 An Ecologically Sustainable Economy ....................................................................................................................4 Meaningful Work ....................................................................................................................................................4 Culture ...................................................................................................................................................................4 -

Whitlam's Children? Labor and the Greens in Australia (2007-2013

Whitlam’s Children? Labor and the Greens in Australia (2007-2013) Shaun Crowe A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University March 2017 © Shaun Crowe, 2017 1 The work presented in this dissertation is original, to the best of my knowledge and belief, except as acknowledged in the text. The material has not been submitted, in whole or in part, for a degree at The Australian National University or any other university. This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. 2 Acknowledgments Before starting, I was told that completing a doctoral thesis was rewarding and brutal. Having now written one, these both seem equally true. Like all PhD students, I never would have reached this point without the presence, affirmation and help of the people around me. The first thanks go to Professor John Uhr. Four and half years on, I’m so lucky to have stumbled into your mentorship. With such a busy job, I don’t know how you find the space to be so generous, both intellectually and with your time. Your prompt, at times cryptic, though always insightful feedback helped at every stage of the process. Even more useful were the long and digressive conversations in your office, covering the world between politics and philosophy. I hope they continue. The second round of thanks go to the people who aided me at different points. Thanks to Guy Ragen, Dr Jen Rayner and Alice Workman for helping me source interviews. Thanks to Emily Millane, Will Atkinson, Dr Lizzy Watt, and Paul Karp for editing chapters. -

The Australian Women's Health Movement and Public Policy

Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Reaching for Health The Australian women’s health movement and public policy Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Gray Jamieson, Gwendolyn. Title: Reaching for health [electronic resource] : the Australian women’s health movement and public policy / Gwendolyn Gray Jamieson. ISBN: 9781921862687 (ebook) 9781921862670 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Birth control--Australia--History. Contraception--Australia--History. Sex discrimination against women--Australia--History. Women’s health services--Australia--History. Women--Health and hygiene--Australia--History. Women--Social conditions--History. Dewey Number: 362.1982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents Preface . .vii Acknowledgments . ix Abbreviations . xi Introduction . 1 1 . Concepts, Concerns, Critiques . 23 2 . With Only Their Bare Hands . 57 3 . Infrastructure Expansion: 1980s onwards . 89 4 . Group Proliferation and Formal Networks . 127 5 . Working Together for Health . 155 6 . Women’s Reproductive Rights: Confronting power . 179 7 . Policy Responses: States and Territories . 215 8 . Commonwealth Policy Responses . 245 9 . Explaining Australia’s Policy Responses . 279 10 . A Glass Half Full… . 305 Appendix 1: Time line of key events, 1960–2011 . -

News Release

HELP RESCUE THE FORESTS WITH THIS FOREST PROTECTION STRATEGY THIS was ASPIRING TO BE AUSTRALIA'S BIGGEST EVER PUBLIC PETITION News Release The Earth Repair Foundation (ERF), an innovative environmental and community education organisation based in the Blue Mountains, is aiming to achieve Australia's most signed petition. This petition calls for the permanent protection of all native forests and an ecologically sustainable future. The petition is already supported by more than 160 diverse community groups, union, business, environmental, indigenous, ethnic, religious and political organisations representing millions of Australians (see list of endorsees overleaf). The petition is seeking to collect over a million signatures. The Forest Protection Petition outlines viable and achievable solutions aiming to protect in perpetuity, Australia's irreplaceable high-conservation value native forests including old-growth and rainforests. It also recommends practical plantation strategies which can sustain the important pulp, paper and timber industries in Australia. The petition began in the early 90's when a group of dedicated forest defenders began a Fast for the Forests on Macquarie Street, Sydney in front of NSW Parliament House. Two individuals fasted for over 30 days as a personal protest and the action ran for 60 days. Since that time the petition has gained an unprecedented support base and aims to be the most influential petition in Australia's history. It advocates a long-term approach to ecologically-sustainable forestry practices, by assisting rural communities with much-needed employment in developing plantation timbers and annual fibre crops and effectively 'reaping only what we sow'. It is a well-known fact that Australia's native forests are being sacrificed to export woodchips to Japan and other countries, while those countries preserve their own native forests as national treasures. -

University of Tasmania Law Review

UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37, NUMBER 2 SPECIAL ISSUE: IMAGINING A DIFFERENT FUTURE, OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO CLIMATE JUSTICE University of Tasmania Law Review VOLUME 37 NUMBER 2 2018 SPECIAL ISSUE: IMAGINING A DIFFERENT FUTURE, OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO CLIMATE JUSTICE Introduction NICKY VAN DIJK, JAN LINEHAN AND PETER LAWRENCE 1 Articles Imagining Different Futures through the Courts: A Social Movement Assessment of Existing and Potential New Approaches to Climate Change Litigation in Australia DANNY NOONAN 25 Justice and Climate Transitions JEREMY MOSS AND ROBYN KATH 70 Ecocide and the Carbon Crimes of the Powerful ROB WHITE 95 Individual Moral Duties Amidst Climate Injustice: Imagining a Sustainable Future STEVE VANDERHEIDEN 116 Lawfare, Standing and Environmental Discourse: A Phronetic Analysis BRENDON MURPHY AND JEFFREY MCGEE 131 Non-Peer Reviewed Article Climate, Culture and Music: Coping in the Anthropocene SIMON KERR 169 The University of Tasmania Law Review (UTLR) has been publishing articles on domestic, international and comparative law for over 50 years. Two issues are published in each volume. One issue is published in winter, and one is published in summer. Contributors We welcome the submission of scholarly and research articles of any length (preferably 4000–10 000 words) on legal topics, particularly those concerning Tasmania, Australia or international law. Articles and papers should be accompanied by a brief (200 word) abstract. Contributions are to be submitted using the online form available at: http://www.utas.edu.au/law/publications/university-of-tasmania-law- review/submission-form. Co-authored articles should be identified as such in the ‘Comments to the Editors’ field and all authors other than the lead author are required complete the University of Tasmania Law Review Submission and Publication Agreement using the form available at: http://www.utas.edu.au/law/publications/university-of-tasmania-law- review/co-author-submission-form. -

Celebrating Australian Greens

MURRAY DARLING BASIN TASSIE FOREST PEACE DEAL THE NZ CAMPAIGN MEMBER PROFILES CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OF THE AUSTRALIAN GREENS CLAIRE JANSEN HAS JUST HAD HER FIRST giving program. “Political parties need money to fund BOOK PUBLISHED, PLAYS ROLLER DERBY their campaigns. Financial support assists with our & SHE IS INVOLVED WITH THE GREENS... capacity to win seats, and when we win enough seats we have the opportunity to implement green policies laire (26 years old) of Hobart works for in government.” Tasmanian Greens Minister Cassy O’Connor, More and more supporters and members of The C volunteers for the Party, is a Greens Party Greens are choosing to join their state regular giving member AND a regular Greens donor. program. Regular gifts enable the party to plan and Claire joined The Greens in 2002 at the age of 16. budget for election campaigns – and manage the day “The Greens were a part of how I grew up. But to day running of the party. “I am glad to help – I know there’s also a time when you decide what you think that my contributions – along with those of others – for yourself and why, and that’s when I joined. help put the party in a stronger position to take on Growing up under John Howard, his policies towards the major parties on important issues of our time asylum seekers and refusal to apologise to the Stolen like climate change, treatment of asylum seekers and Generations, watching Labor get trumped by the equality for same sex marriages” forestry industry - the Greens offered a future for society and the environment that no other party did.” Claire’s keen interest in The Greens – and the future If you, like Claire, would like to become a regular donor of the party motivated her to join Tas Greens regular please fill out and send us the form below. -

Sida Application

SIDA APPLICATION VO1 2016-2018 Green Forum Pustegränd 1-3 118 20 Stockholm [email protected] ABBREVIATIONS AGF African Greens Federation AGP Albanian Green Party CDN Cooperation & Development Network of Eastern Europe CEMAT Centro Mesoamericano de Estudios sobre Tecnolgìa Apropriada, Guatemala CEPROCA Centro de Produccion, Promocion y Capacitacion, Bolivia CSO Civil Society Organization EE Eastern Europe EGP European Green Parties (The Green group of the EU Parliament) ENoPS European Network of Political Foundations EVS European Voluntary Service (Programme) FYEG Federation of Young European Greens GEF Green European Foundation (PAO for the Green Group in EU) GeYG Georgian Young Greens GGWN Global Greens Women’s Network Groen Flemish Greens LGBT (Q) Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual, Transsexual (Questioning) NGO Non-Governmental Organization ODA Official Development Assistance PAO Politically Affiliated Organization PVE Partido verde ecología (The Bolivian Green Party) PME Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation PWC Price Waterhouse Coopers – Previous auditors of Green Forum PYPA Programme for Young Politicians in Africa Sage Accounting Software, used in AGF SDGs Sustainable Development Goals SGY Serbian Green Youth WF Westminster Foundation (UK). British found. handling PAO-support of British greens INDEX A. ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION 4 B. PROGRAMME DESCRIPTION 5 2 1. SUMMARY PROGRAMME DESCRIPTION AND APPROACH 5 2. GREEN FORUM AND THE GREEN MOVEMENT 6 3. OVERALL CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS 7 4. ANALYSIS OF PROBLEMS AND PARTNERS 8 4.1 Problem Analysis 8 4.2 Analysis of prospects for the programme’s feasibility 8 4.3 Analysis of cooperation partners and programmes 9 5. GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND THE STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK 10 5.1 The revised Green Forum Strategy and the overall objectives of the programme 10 5.2 Indicators 11 5.3 Human Rights Based Approach 11 6.