Viggo Jacobsen & the Optimist Dinghy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courier Gazette

T he Courier-G r ie. ROCKLAND GAZETTE ESTABLISHED 1S4O.) ROCKLAND COCKIER EHTAIII.ISHEI) 1S74.| O n |1rcss is % ^rtlftmchcan $cber that Iftobcs Ijjc &?lorlb at £too Dollars a ilcar l TWO DOLLARS A YEAR IN ADYANCBi 1 MINGLE COPIES PRICE FIVE CKNT8, V o l. 8 , — N ew S e r ie s . ROCKLAND, MAINE, TUESDAY, APRILS, 1889. N umber 13. ? p p ? W here cnt» I invest my s h t in g s Hint, th e y H.GALI.ERT’S may lie safe nnil yet yield me n good rate of Interest? T I I 13 OFFERINC House Furnishing Co. (O F M A IN E) OF •AYR IT S ST O CK H O LDERDERR 10 PER LADIES’ SPRINC CENT ’cr A nnum DIVIDENDS JANUARY ANU JULY. For full particnlars call on or write JACKETS! DAV1I) W. SEARS, 17 Milk SI. S-20 ROOM f», BOSTON. Or the Treasurer of the Company, Portland, Me JACKETS ! = HOTEL ST. CTEKB5Sfi?HBW3iWH Fifth Ave. and 39th St., N. Y. JACKETS! Zfcu American Plan $4 OD per day; Bath and Parlors extra. European Plan $1.50 per day and upwards, Among the many New Goods we are LON NUTTER, : Proprietor. J now daily receiving for our Spring Fornv-rly op Bangor Steamship Line. j Trade, we call especial attention to ROCKLAND TOW BOAT our COMPAMY. NEW STYLES OF id B ritannia. This Company has Two Good Boats, one large for outside work, and the other smaller for inside Ladies’ Jersey and Cloth work, and are prepared to receive orders for any towing job that may come up, either Inside or Outside, Anywhere Along J a c k e ts ! the Coast of Maine. -

Berliner Regattakalender 2021

Berliner Regattakalender 2021 Stand: 08.03.2021 Die Durchführung von Regatten liegt in der Verantwortung der veranstaltenden Vereine. Eventuelle Absagen sind von diesen zu entscheiden und mitzuteilen. Der Regattakalender 2021 des Berliner Segler-Verbandes wurde am 25.11.2020 vom Wettsegelausschuss beschlossen. Die Klassenobleute und Vereine werden gebeten, Anträge für Berliner Meisterschaften laut Berliner Meisterschaftsordnung bis spätestens 30.11.2020 und die fehlenden oder zu korrigierenden Ranglistenfaktoren bis 31.12.2020 per Email an „wettsegeln @ berliner-segler-verband.de“ beim Berliner Segler-Verband einzu- reichen. März 2021 Dahme Müggelsee Tegel Unterhavel Wannsee Zeuthen Mo 1. Di 2. Mi 3. Do 4. Fr 5. Sa 6. So 7. Mo 8. Di 9. Mi 10. Do 11. Fr 12. Sa 13. So 14. Mo 15. Di 16. Mi 17. Do 18. Fr 19. Sa 20. Frostbite End Laserregatta SZV (1.1) Std, Radial, 4.7 So 21. DBYC SGZ Mo 22. Di 23. Mi 24. Do 25. Fr 26. Sa 27. So 28. Mo 29. Di 30. Mi 31. Tag Datum = Schulferien in Berlin BM = Berliner Meisterschaft BJoM = Berliner Juniorenmeisterschaft BJM = Berliner Jugendmeisterschaft BJüM = Berliner Jüngstenmeisterschaft BE = Berliner Bestenermittlung Graue Schrift = Keine offene Veranstaltung Berliner Regattakalender 2021 Stand 08.03.2021 Seite 2 von 10 April 2021 Dahme Müggelsee Tegel Unterhavel Wannsee Zeuthen Do 1. Kar 2. Fr Preis der Malche Sa 3. Pirat (1.26) Oster TSC 4. So Oster 5. Mo Di 6. Mi 7. Do 8. Fr 9. Frühjahrs-Cup und Klaus-Harte- Piraten-Cup Spandauer Yardstick Auftakt Sa 10. Gedächtnis-Preis/ Finn (1.05), SpYC (Sa) 52. Frühlings-Cup 420 (1.1), VA (1.2), Pirat (1.2), Rüdiger-Weinholz- O-Jolle (1.14) OK (1.1.) Preis So 11. -

OL-Sejlere Gennem Tiden

Danske OL-sejlere gennem tiden Sejlsport var for første gang på OL-programmet i 1900 (Paris), mens dansk sejlsport debuterede ved OL i 1912 (Stockholm) - og har været med hver gang siden, dog to undtagelser (1920, 1932). 2016 - RIO DE JANIERO, BRASILIEN Sejladser i Finnjolle, 49er, 49erFX, Nacra 17, 470, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Bronze i Laser Radial: Anne-Marie Rindom Bronze i 49erFX: Jena Mai Hansen og Katja Salskov-Iversen 4. plads i 49er: Jonas Warrer og Christian Peter Lübeck 12. plads i Nacra 17: Allan Nørregaard og Anette Viborg 16. plads i Finn: Jonas Høgh-Christensen 25. plads i Laser: Michael Hansen 12. plads i RS:X(m): Sebastian Fleischer 15. plads i RS:X(k): Lærke Buhl-Hansen 2012 - LONDON, WEYMOUTH Sejladser i Star, Elliot 6m (matchrace), Finnjolle, 49er, 470, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Sølv i Finnjolle: Jonas Høgh-Christensen. Bronze i 49er: Allan Nørregaard og Peter Lang. 10. plads i matchrace: Lotte Meldgaard, Susanne Boidin og Tina Schmidt Gramkov. 11. plads i Star: Michael Hestbæk og Claus Olesen. 13. plads i Laser Radial: Anne-Marie Rindom. 16. plads i 470: Henriette Koch og Lene Sommer. 19. plads i Laser: Thorbjørn Schierup. 29. plads i RS:X: Sebastian Fleischer. 2008 - BEIJING, QINGDAO Sejladser i Yngling, Star, Tornado, 49er, 470, Finnjolle, Laser, Laser Radial og RS:X. Resultater Guld i 49er: Jonas Warrer og Martin Kirketerp. 6. plads i Finnjolle: Jonas Høgh-Christensen. 19. plads i RS:X: Bettina Honoré. 23. plads i Laser: Anders Nyholm. 24. plads i RS:X: Jonas Kældsø. -

Sailing Week Special Edition

Sailing Week special edition August 2013 NEWHAVEN AND SEAFORD SAILING CLUB SAILING WEEK 2013. If you have never been to Sailing Week you are missing out on a great part of being a mem- ber of NSSC. You do not have to attend every part of the week. Pick and Mix. Some members bring their families and camp for the week – without sailing. Some members work mornings and come just for the afternoon races. Some members come for the evening social events. The event is open to non members – so you can bring friends to join in the fun. The Galley will be open all day for food and drinks. The bar is open at lunchtimes and evenings. Make 2013 the year that you come along to the Seaford Clubhouse and experience:- Sailing Week Saturday 3 rd August – Sunday 11 th August If the conditions are not good to sail on the sea we will use facilities at Piddinghoe. Sailing week timetable Day Morning Afternoon Evening Saturday Set up camp Free Fun Sailing ? Bar Open Sunday AM Series 1.8 -2.8 PM race 1.6 Bar Open Monday Cadet Races – approxi- Series Handicap Races Quiz Night mately If possible 2 races per day – 1 Tuesday 45 minutes long for the Len on Friday (prize Giving) if 9 Bring and Burn BBQ Miller Trophy. races – best 6 count. Cook your own! Wednesday Sailing For Adults – a series of Prizes for different classes as Jive Night Thursday informal novelty races. well as fun prizes. Live band and attractions Friday Fish and Chip night Saturday Expedition to the Cuckmere Bar Open Sunday Class Championships 1 &2 PM series 1.7 Bar Open Race and camping fees Race/sailing fees Member Non-member – Camping fees – Camping fees – payable per sailor SMALL TENT (<4) LARGE TENT (4+) Whole event Free £35 £15 £30 (30/7-7/8) Expedition Free £5 Commodores bit As mainsheet is relatively easy to produce, cut and paste, and now we don't try and email so file size doesn't matter, we can now put more photos in, so if you have anything to say or pho- tos to share, let the officers know. -

New GP Design Unveiled at the Worlds in Sri Lanka Editor’S Letter Contents

S pr in g www.gp14.org GP14 Class International Association 20 11 New GP design unveiled at the worlds in Sri Lanka Editor’s letter Contents One of the most important themes of this issue is training. The Features importance of getting newcomers into the sport cannot be over- emphasised in these days when there is so much competition for 4 President’s piece Return to Abersoch everyone’s time and money. With any luck the recession will make Ian Dobson on expectation people think twice about flying off abroad and more interested in a 6 Welcome to Gill Beddow 13 versus reality at the Nationals local low-cost hobby which will teach them and their children a 8 From the forum new skill while providing an instant social life. View from astern Phil Green on the Nationals Phil Hodgkins, a young sailor from ??, has recently been elected to Racing 16 from the other end of the fleet the Association Committee with responsibility for training and you 11 Championship round-up can read about his plans for training days organised for those clubs Book review who would like them. The RYA is also very interested in training and Hugh Brazier tells how Goldilocks Overseas reports 32 has recently expanded their remit to getting adults onto the water, learned the racing rules rather than concentrating on youngsters with their OnBoard 18 News from Ireland scheme. You can read about their latest initiative, Activate your 21 The Australian trapeze Fleet, and how it can help you. I have seen first-hand how a good training scheme, pulling in Area reports newcomers, helping them to build their skills and – most 24 North West Region importantly – to become involved in the work of helping others in the club, can build up a club from only having a few half-hearted 26 North East Area GP sailors in ageing boats to a large, young and competitive fleet in 27 Scottish Area the space of a few years. -

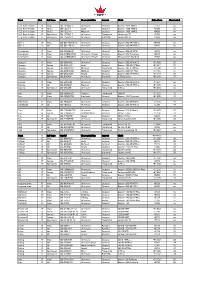

Boat Nat Sail Type Model Characteristics Layout Cloth Price Euro Class Label

Boat Nat Sail type Model Characteristics Layout Cloth Price Euro Class Label 12,5 Kvm Krysser IT Main OD-125MA-1 All-round Crosscut Dacron 190B HMTO € 763 no 12,5 Kvm Krysser IT Jib C1 OD-125JL-1 Light Crosscut Dacron 190B HMTO € 480 no 12,5 Kvm Krysser IT Jib C2 OD-125JA-1 Medium Crosscut Dacron 190B HMTO € 428 no 12,5 Kvm Krysser IT Spinnaker OD-125SPIT-1 All-round Trioptimal Superkote 75 € 502 no 12,5 Kvm Krysser IT Spinnaker OD-125SPIB-1 All-round Butterfly Superkote 75 € 428 no BB 11 IT Main OD-BB11MAIN-12 All-round Crosscut Dacron 200 AP HTPlus € 769 no BB 11 IT Jib OD-BB11JIB-12 All-round Crosscut Dacron 200 AP HTPlus € 493 no Contender IT Main OD-CONMA01 All-round Crosscut Dacron 200 AP MTO € 874 no Contender IT Main OD-CONMAIT02 All-round / Power Crosscut Dacron 4,52 Polypreg € 874 no Contender IT Main OD-CONMAIT03 All-round / Power Crosscut Flexx Aramid Black 07 € 998 no Dragon IT Main OD-DRMA05 All-round Crosscut Dacron 280 AP HMTO € 1.550 37 Dragon IT Genoa OD-DRGLC01 Light Crosscut Dacron 180 OD HTPlus € 1.217 37 Dragon IT Genoa OD-DRGMT02 Medium Trioptimal Dacron 240 B HTPlus € 1.248 37 Dragon IT Genoa OD-DRGMC02 Medium Crosscut Dacron 240 B HTPlus € 1.165 37 Dragon IT Genoa OD-DRGHC05 Heavy Crosscut Dacron 280 AP HTPlus € 1.144 37 Dragon IT Spinnaker OD-DRSA01 All-round Butterfly 0,75 Dynalite € 1.342 37 Express IT Main OD-EXMA09 All-round Crosscut Dacron 280 AP HTPlus € 1.581 no Express IT Jib OD-EXJM09 Medium Crosscut Dacron 240 AP HTPlus € 1.165 no Express IT Spinnaker OD-EXSA09 All-round Trioptimal 0,75 oz € 1.506 no -

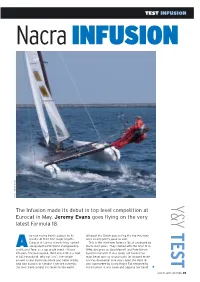

Yachts Yachting Magazine NACRA F18 Infusion Test.Pdf

TEST INFUSION Nacra INFUSION S N A V E Y M E R E J O T O H P Y The Infusion made its debut in top level competition at & Eurocat in May. Jeremy Evans goes flying on the very latest Formula 18. Y T ny new racing boat is judged by its although the Dutch guys racing the top Infusions results. At their first major regatta — were clearly pretty good as well. Eurocat in Carnac in early May, ranked This is the third new Formula 18 cat produced by E A alongside the F18 World championship Nacra in 10 years. They started with the Inter 18 in and Round Texel as a top grade event — Nacra 1996, designed by Gino Morrelli and Pete Melvin S Infusions finished second, third and sixth in a fleet based in the USA. It was quick, but having the of 142 Formula 18. Why not first? The simple main beam and rig so unusually far forward made answer is that Darren Bundock and Glenn Ashby, it tricky downwind. Five years later, the Inter 18 T who won Eurocat in a Hobie Tiger are currently was superseded by a new Nacra F18 designed by the most hard-to-beat cat racers in the world, Alain Comyn. It was quick and popular, but could L YACHTS AND YACHTING 35 S N A V E Y M E R E J S O T O H P Above The Infusion’s ‘gybing’ daggerboards have a thicker trailing edge at the top, allowing them to twist in their cases and provide extra lift upwind. -

Société Des Régates De Douarnenez, Europe Championship Application

Société des Régates de Douarnenez, Europe championship Application Douarnenez, an ancient fishing harbor in Brittany, a prime destination for water sports lovers , the land of the island, “Douar An Enez” in Breton language The city with three harbors. Enjoy the unique atmosphere of its busy quays, wander about its narrows streets lined with ancient fishermen’s houses and artists workshops. Succumb to the charm of the Plomarch walk, the site of an ancient Roman settlement, visit the Museum Harbor, explore the Tristan island that gave the city its name and centuries ago was the lair of the infamous bandit Fontenelle, go for a swim at the Plage des Dames, “the ladies’ beach”, a stone throw from the city center. The Iroise marine park, a protected marine environment The Iroise marine park is the first designated protected marine park in France. It covers an area of 3500 km2, between the Islands of Sein and Ushant (Ouessant), and the national maritime boundary. Wildlife from seals and whales to rare seabirds can be observed in the park. The Société des Régates de Douarnenez, 136 years of passion for sail. The Société des Régates de Douarnenez was founded in 1883, and from the start competitive sailing has been a major focus for the club. Over many years it has built a strong expertise in the organization of major national and international events across all sailing series. sr douarnenez, a club with five dynamic poles. dragon dinghy sailing kiteboard windsurf classic yachting Discovering, sailing, racing Laser and Optimist one Practicing and promoting Sailing and promoting the Preserving and sailing the Dragon. -

WBYC Membership Packet

Willow Bank Yacht Club has been a fixture on the Cazenovia Lake shoreline since 1949. Originally formed as a sailing club, over the years it has become a summer home to many Cazenovia and surrounding area families. Willow Bank provides its members with outstanding lake frontage and views, docks, private boat launch, picnic area, beach, swimming area, swimming lessons, sailing lessons, children’s programming, Galley take-out restaurant and a lively social program. The adult sailing program at Willow Bank is one of the most active in Central New York. Active racing fleets include: Finn, Flying Dutchman, Laser, Lightning and Sunfish. Each of these fleets host a regatta over the summer and fleet members will often travel to other area clubs for regattas as well. Formal club point races are held on Sundays. These are races to determine a club champion in each fleet. This format provides for a fun competition within the fleets. On Saturdays, the club offers Free-for-All races which allow members to go out and get some experience racing in any class of sailboat. Adults also have sailing opportunities during the week with our Women of Willow Bank fleet sailing and socializing on Wednesday evenings and, on Thursday evenings, we now have an informal sailing and social program for all members. In addition, we offer group adult lessons and private lessons for anyone looking to learn how to sail. For our youngest members we have a great sand beach and a lifeguarded swimming area which allows hours of summer fun! Swimming lessons, sailing lessons, and Junior Fleet racing, round out our youth programs. -

Annual General Meeting Season 2008 - 2009

Annual General Meeting Season 2008 - 2009 AGENDA FOR ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING, 26 MAY 2009 1. Attendance & Apologies 2. Confirmation of Minutes of AGM held 21st May 2008 3. Business arising from 21st May 2008 meeting 4. Reports 5. Affiliation Fees for 2008/2009 Season 6. Election of Board Members 7. Confirmation of Sub-Committee Chairpersons for 2008/2009 8. Confirmation of Yachting Australia Delegates 9. Confirmation of Auditor 10. Close of Meeting 2008/09 Yachting SA Roll of Honour The Board of Yachting SA congratulates the following South Australian sailors on their outstanding achievements. YSA Awards for Season 2007/2008 Sailor of the Year ~ jointly awarded to Craig McPhee & Gillian Berry Junior Sailor of the Year ~ awarded jointly to Lauren Thredgold & Megan Soulsby Volunteer of the Year ~ awarded jointly to Gary Day & Greg Hampton President’s Award ~ jointly awarded to Les Harper & David Tillett 2008/2009 National Champions Australian Sharpie Malcolm Higgins Sam Sanderson Andrew Chisolm National Champion Brighton & Seacliff YC Brighton & Seacliff YC Brighton & Seacliff YC International Fireball Robins Inns Joel Coultas National Champion Adelaide SC Adelaide SC International 505 Alexander Higgins Jordan Spencer National Champion Brighton & Seacliff YC Brighton & Seacliff YC Laser Sean Homan Grand Master Adelaide SC National Champion Mosquito Mk II Cat. Warwick Kemp Emily Fink National Champion Adelaide SC Adelaide SC Yvonne 20 Paul Hawkins Graham Lovell National Champion Victor Harbor YC Victor Harbor YC Yachting SA Annual Report 2008/2009 May 2009 ITEM 1 Attendance & Apologies Attendance Register and Voting Rights All attendees are required to sign the attendance register before the meeting commences or upon arrival. -

Performance Award Archives

Performance Award Archives The Performance Award category was introduced in 1994 and since this time many great achievements in the sport of yachting have been recognised. The category was previously known as the Merit Award, in 2010 the category was renamed the Performance Award. Year Awardees Details Peter Burling & Blair Tuke 1st 49er World Championships 2019 & 2020 Logan Dunning Beck & Oscar 5th 49er World Championships 2019 Gunn Honda Marine - David 1st JJ Giltinan Trophy for 3rd consecutive year McDiarmid, Matt Steven & Brad Collins Josh Junior 1st Finn Gold Cup 2020 (World Championships) Knots Racing - Nick Egnot- 2nd World Sailing Match Race Rankings 2020 Johnson, Sam Barnett, Bradley McLaughlin & Zak 2020 Merton Scott Leith 1st Laser World Masters 2020 Alex Maloney & Molly Meech 1st 49erFX Oceania Championship 2019 2nd 49erFX Oceania Championship 2020 2nd World Cup Series Enoshima 2019 Andy Maloney 6th Finn Gold Cup 2020 (World Championships) Sam Meech 8th Laser World Championships 2020 Lukas Walton-Keim & Justina 3rd Mixed Formula Kite European Championships 2019 Kitchen Micah Wilkinson & Erica 7th Nacra17 World Championships 2020 Dawson Peter Burling & Blair Tuke 1st 49er European Championships 2019 1st 49er Olympic Test Event 2019 Logan Dunning Beck & Oscar 1st 49er Kiel Week 2019 Gunn George Gautrey 3rd place Laser Worlds 2019 Knots Racing: Nick Egnot- 1st Grade 1 Match Race Germany 2019 Johnson, Sam Barnett, 1st New Zealand Match Racing Nationals 2019 Bradley McLaughlin, Zak 3rd World Sailing Match Race Rankings 2019 Merton -

NOTICE of RACE 29Er Midwinters West

Coronado Yacht Club NOTICE OF RACE 1631 Stand Way Coronado Ca. 92118 Office 619-435-0522 29er Midwinters West Cell 619-994-1687 March 22nd – 24th, 2019 This is a selection event for U.S. sailors for the Youth Sailing World Championships. As such, it is a Protected Competition per US Sailing Regulation 12.03, see NoR 10 and NoR 11 below. The Organizing Authority (OA) for this event is Coronado Yacht Club. 1. VENUE 1.1 All on-shore activities will occur at Coronado Yacht Club (CYC), which is located at 1631 Strand Way, Coronado CA 92118 1.2 The racing area will be on San Diego South Bay. 2. RULES 2.1 The regatta will be governed by the rules as defined in the 2017-2020 Racing Rules of Sailing. 2.2 All competitors (i.e. both skipper and crew) shall carry a SOLAS approved whistle while aboard their boat. A Discretionary Penalty [DP] shall apply to violations of this rule. 2.3 All competitors shall wear, except briefly to change clothes, an inherently buoyant (i.e. not inflatable) Personal Flotation Device (PFD) certified to either US Coast Guard, CE EN393, or ISO 12402-5 (Level 50) standards while aboard their boat. This replaces similar International 420 and International 29er Class Association rules. A Discretionary Penalty [DP] shall apply to violations of this rule. 2.4 International 29er Class Rule C.10.3(a)(vi), concerning all-women teams carrying a red rhombus shape on their mainsail, shall not apply. 3. ELIGIBILITY 3.1 This event is open to boats of the International 29er Class 3.2 All competitors shall be current members of the International 29er Class Association.