Record 2004 Archivist’S Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey 43-51 Cowper Wharf Road September 2013 Woolloomooloo NSW 2011 w: www.mgnsw.org.au t: 61 2 9358 1760 Introduction • This report is presented in two parts: The 2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and the 2013 NSW Small to Medium Museum & Gallery Survey. • The data for both studies was collected in the period February to May 2013. • This report presents the first comprehensive survey of the small to medium museum & gallery sector undertaken by Museums & Galleries NSW since 2008 • It is also the first comprehensive census of the museum & gallery sector undertaken since 1999. Images used by permission. Cover images L to R Glasshouse, Port Macquarie; Eden Killer Whale Museum , Eden; Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, Bathurst; Lighting Ridge Museum Lightning Ridge; Hawkesbury Gallery, Windsor; Newcastle Museum , Newcastle; Bathurst Regional Gallery, Bathurst; Campbelltown arts Centre, Campbelltown, Armidale Aboriginal Keeping place and Cultural Centre, Armidale; Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington; Australian Country Music Hall of Fame, Tamworth; Powerhouse Museum, Tamworth 2 Table of contents Background 5 Objectives 6 Methodology 7 Definitions 9 2013 Museums and Gallery Sector Census Background 13 Results 15 Catergorisation by Practice 17 2013 Small to Medium Museums & Gallery Sector Survey Executive Summary 21 Results 27 Conclusions 75 Appendices 81 3 Acknowledgements Museums & Galleries NSW (M&G NSW) would like to acknowledge and thank: • The organisations and individuals -

Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656

The University of Sydney Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656 The address of the Law School is: The University of Sydney Law School 173-5 Phillip Street Sydney, N.S.W. 2000 Telephone (02) 232 5944 Document Exchange No: DX 983 Facsimile: (02) 221 5635 The address of the University is: The University of Sydney N.S.W. 2006 Telephone 351 2222 Setin 10 on 11.5 Palatino by the Publications Unit, The University of Sydney and printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, Sydney. Text printed on 80gsm recycled bond, using recycled milk cartons. Welcome from the Dean iv Location of the Law School vi How to use the handbook vii 1. Staff 1 2. History of the Faculty of Law 3 3. Law courses 4 4. Undergraduate degree requirements 7 Resolutions of the Senate and the Faculty 7 5. Courses of study 12 6. Guide for law students and other Faculty information 24 The Law School Building 24 Guide for law students 24 Other Faculty information 29 Law Library 29 Sydney Law School Foundation 30 Sydney Law Review 30 Australian Centre for Environmental Law 30 Institute of Criminology 31 Centre for Plain Legal Language 31 Centre for Asian and Pacific Law 31 Faculty societies and student representation 32 Semester and vacation dates 33 The Allen Allen and Hemsley Visiting Fellowship 33 Undergraduate scholarships and prizes 34 7. Employment 36 Main Campus map 39 The legal profession in each jurisdiction was almost entirely self-regulating (and there was no doubt it was a profession, and not a mere 'occupation' or 'service industry'). -

Golden Yearbook

Golden Yearbook Golden Yearbook Stories from graduates of the 1930s to the 1960s Foreword from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal ���������������������������������������������������������5 Message from the Chancellor ��������������������������������7 — Timeline of significant events at the University of Sydney �������������������������������������8 — The 1930s The Great Depression ������������������������������������������ 13 Graduates of the 1930s ���������������������������������������� 14 — The 1940s Australia at war ��������������������������������������������������� 21 Graduates of the 1940s ����������������������������������������22 — The 1950s Populate or perish ���������������������������������������������� 47 Graduates of the 1950s ����������������������������������������48 — The 1960s Activism and protest ������������������������������������������155 Graduates of the 1960s ���������������������������������������156 — What will tomorrow bring? ��������������������������������� 247 The University of Sydney today ���������������������������248 — Index ����������������������������������������������������������������250 Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������� 252 Produced by Marketing and Communications, the University of Sydney, December 2016. Disclaimer: The content of this publication includes edited versions of original contributions by University of Sydney alumni and relevant associated content produced by the University. The views and opinions expressed are those of the alumni contributors and do -

Camperdown and Darlington Campuses

Map Code: 0102_MAIN Camperdown and Darlington Campuses A BCDEFGHJKLMNO To Central Station Margaret 1 ARUNDEL STREETTelfer Laurel Tree 1 Building House ROSS STREETNo.1-3 KERRIDGE PLACE Ross Mackie ARUNDEL STREET WAY Street Selle Building BROAD House ROAD Footbridge UNIVERSITY PARRAMATTA AVENUE GATE LARKIN Theatre Edgeworth Botany LANE Baxter's 2 David Lawn Lodge 2 Medical Building Macleay Building Foundation J.R.A. McMillan STREET ROSS STREET Heydon-Laurence Holme Building Fisher Tennis Building Building GOSPER GATE AVENUE SPARKES Building Cottage Courts STREET R.D. Watt ROAD Great Hall Ross St. Building Building SCIENCE W Gate- LN AGRICULTURE EL Bank E O Information keepers S RUSSELL PLACE R McMaster Building P T Centre UNIVERSITY H Lodge Building J.D. E A R Wallace S Badham N I N Stewart AV Pharmacy E X S N Theatre Building E U ITI TUNN E Building V A Building S Round I E C R The H Evelyn D N 3 OO House ROAD 3 D L L O Quadrangle C A PLAC Williams Veterinary John Woolley S RE T King George VI GRAFF N EK N ERSITY Building Science E Building I LA ROA K TECHNOLOGY LANE N M Swimming Pool Conference I L E I Fisher G Brennan MacCallum F Griffith Taylor UNIV E Centre W Library R Building Building McMaster Annexe MacLaurin BARF University Oval MANNING ROAD Hall CITY R.M.C. Gunn No.2 Building Education St. John's Oval Old Building G ROAD Fisher Teachers' MANNIN Stack 4 College Manning 4 House Manning Education Squash Anderson Stuart Victoria Park H.K. -

ITER: the Way for Australian Energy Research?

The University of Sydney School of Physics 6 0 0 ITER: the Way for Australian 2 Energy Research? Physics Alumnus talks up the Future of Fusion November “World Energy demand will Amongst the many different energy sources double in the next 50 years on our planet, Dr Green calls nuclear fusion the – which is frightening,” ‘philosopher’s stone of energy’ – an energy source s a i d D r B a r r y G r e e n , that could potentially do everything we want. School of Physics alumnus Appropriate fuel is abundant, with the hydrogen and Research Program isotope deuterium and the element lithium able to Officer, Fusion Association be derived primarily from seawater (as an indication, Agreements, Directorate- the deuterium in 45 litres water and the lithium General for Research at the in one laptop battery would supply the fuel for European Commisison in one person’s personal electricity use for 30 years). Brussels, at a recent School Fusion has ‘little environmental impact or safety research seminar. concerns’: there are no greenhouse gas emissions, “The availability of and unlike nuclear fission there are no runaway cheap energy sources is a nuclear processes. The fusion reactions produce no thing of the past, and we radioactive ash waste, though a fusion energy plant’s Artists’s impression of the ITER fusion reactor have to be concerned about structure would become radioactive – Dr Green the environmental impacts reckoned that the material could be processed and of energy production.” recycled within around 100 years. Dr Green was speaking in Sydney during his nation-wide tour to promote ITER, the massive Despite all these benefits, international research collaboration to build a fusion-energy future is still a long an experimental device to demonstrate the way off. -

5-7 December, Sydney, Australia

IRUG 13 5-7 December, Sydney, Australia 25 Years Supporting Cultural Heritage Science This conference is proudly funded by the NSW Government in association with ThermoFisher Scientific; Renishaw PLC; Sydney Analytical Vibrational Spectroscopy Core Research Facility, The University of Sydney; Agilent Technologies Australia Pty Ltd; Bruker Pty Ltd, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences; and the John Morris Group. Conference Committee • Paula Dredge, Conference Convenor, Art Gallery of NSW • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Boris Pretzel, (IRUG Chair for Europe & Africa), Victoria and Albert Museum, London • Beth Price, (IRUG Chair for North & South America), Philadelphia Museum of Art Scientific Review Committee • Marcello Picollo, (IRUG chair for Asia, Australia & Oceania) Institute of Applied Physics “Nello Carrara” Sesto Fiorentino, Italy • Danilo Bersani, University of Parma, Parma, Italy • Elizabeth Carter, Sydney Analytical, The University of Sydney, Australia • Silvia Centeno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA • Wim Fremout, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium • Suzanne de Grout, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, The Netherlands • Kate Helwig, Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, Canada • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Richard Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA • Gillian Osmond, Queensland Art Gallery|Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia • Catherine Patterson, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA -

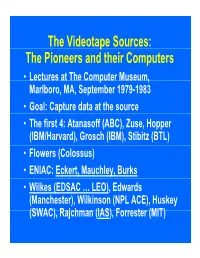

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

The University Archives – Record 2015

THE UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES 2015 Cover image: Students at Orientation Week with a Dalek, 1983. [G77/1/2360] Forest Stewardship Council (FSC®) is a globally recognised certification overseeing all fibre sourcing standards. This provides guarantees for the consumer that products are made of woodchips from well-managed forests, other controlled sources and reclaimed material with strict environmental, economical social standards. Record The University Archives 2015 edition University of Sydney Telephone Directory, n.d. [P123/1085] Contact us [email protected] 2684 2 9351 +61 Contents Archivist’s notes............................... 2 The pigeonhole waltz: Deflating innovation in wartime Australia ............................ 3 Aboriginal Photographs Research Project: The Generous Mobs .......................12 Conservatorium of Music centenary .......................................16 The Seymour Centre – 40 years in pictures ........................18 Sydney University Regiment ........... 20 Beyond 1914 update ........................21 Book review ................................... 24 Archives news ................................ 26 Selected Accession list.................... 31 General information ....................... 33 Archivist‘s notes With the centenary of WWI in 1914 and of ANZAC this year, not seen before. Our consultation with the communities war has again been a theme in the Archives activities will also enable wider research access to the images during 2015. Elizabeth Gillroy has written an account of where appropriate. a year’s achievements in the Beyond 1914 project. The impact of WWI on the University is explored through an 2015 marks another important centenary, that of the exhibition showing the way University men and women Sydney Conservatorium of Music. To mark this, the experienced, understood and responded to the war, Archives has made a digital copy of the exam results curated by Nyree Morrison, Archivist and Sara Hilder, from the Diploma of the State Conservatorium of Music, Rare Books Librarian. -

A Check-List of the Fishes Recorded from Australia. Part I. Australian Museum Memoir 5: 1–144

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS McCulloch, Allan R., 1929. A check-list of the fishes recorded from Australia. Part I. Australian Museum Memoir 5: 1–144. [29 June 1929]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1967.5.1929.473 ISSN 0067-1967 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia CHECK~LIST OF THE FISHES RECORDED FROM AUSTRALIA. By (the late) ALLAN R. MCOULLOCH. Class LEPTOCARDII. Order AMPHIOXI. Family BRANOHIOSTOMID1E. Genus BRANCHIOSTOMA Costa, 1834. 1834. Brachiostoma Oosta, Ann. Zoo!. (Oenni Zoo!.) Napol. 1834, p. 49. Type, Limax lanceolatus Pall as (fide Jordan, Gen. Fish.). BRACHIOSTOMA BELCHERI (Gray). 1847. Amphioxus belcheri Gray, Proc. ZooL Soc. (Lond.), pt. xv, May 17, 1847, p. 35. Lundu R., Borneo. Queensland, East Indies, Maldives, Oeylon, Japan. Family EPIGONIOHTHYID..;E. Genus EPIGONICHTHYS Peters, 1877. 1877. Epigonichthys Peters, Monatsb. Akad. Wiss. Berlin, June 1876 (1877), p. 322. Orthotype, E. cultdlus Peters. 1893. Paramphioxus Haeckel, ZooI. Forschr. Austr. (Semon) i, 1893, p. xiii. Logotype, Epigonichthys cultellus Peters. EPIGONICHTHYS AUSTRALIS (Raff). 1912. Asymmetron australis Raff, ZooI. Res. Endeavour, pt. iii, 1912, p. 303, pI. xxxvii, figs. 1-16. South of St. Francis Is., Great Australian Bight; 35 faths. South Australia. EPIGONICHTHYS BASSANUS (Gunther). 1884. Branchiostomabassanum Giinther, Rept. Zool. OolI. Alert, Aug. 1, 1884, p. 31. Bass Straits. New South Wales, Tasmania, South Austrrulia. EPIGONICHTHYS CULTELLUS Peters. 1877. Epigonichthys cultellus Peters, Monatsber. Akad. Wiss. Berlin, June 1876 (1877), p. -

The Bunyip As Uncanny Rupture: Fabulous Animals, Innocuous Quadrupeds and the Australian Anthropocene

The Bunyip as Uncanny Rupture: Fabulous Animals, Innocuous Quadrupeds and the Australian Anthropocene Penny Edmonds ‘But it is also said to be something more than animal, and among its supernatural attributes is the cold, awesome, uncanny feeling which creeps over a company at night when the Bunyip becomes the subject of conversation’ Rosa Praed, ‘The Bunyip’, 1891. Y LOVE AFFAIR WITH MUSEUMS BEGAN WHEN I WAS SEVEN. I SAW A BUNYIP’S HEAD in a glass case, a strange, unsettling creature with a one-eyed blind M stare, a cycloptic monster. I was small and I stood up on my toes to see the creature through the glass. On show, the bunyip was mounted in a tall, ornate nineteenth-century wooden cabinet. The typed paper label gave scientific verification: ‘A bunyip’s head, New South Wales. 1841.’ I recall the palpable shock of it, and my mixed childhood emotions: bunyips were real. With its long jawbone wrapped in fawn-coloured fur, it was a decapitated Australian swamp- dweller preserved. Yet, the horrific creature looked so sad, and with its sightless eye, gaping mouth and cartoonish backward drooping ears. It was a creature of pathos—a gormless, goofy redhead, a ranga, a total outsider.1 1 A ‘ranga’ is Australian slang for a red headed person, once pejorative, but now also used in the positive. The term was entered into the Australian Oxford Dictionary in 2012. Thanks to Lynette Russell for re-acquainting me with this object, known as the Macleay Museum ‘bunyip’ (The Macleay Museum, Sydney University, Registration number MAMU NHM.45). -

SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine

SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine Spring 2006 SYDNEY ALUMNI Magazine 8 10 14 18 RESEARCH: THE GENDER SELECTOR FEATURE: PEAK PERFORMERS PROFILE: COONAN THE AGRARIAN ESSAY: DEAD MEDIA Spring 2006 features 10 PEAK PERFORMERS Celebrating 100 years of physical and health education. 14 COONAN THE AGRARIAN Federal Communications Minister Helen Coonan: Editor Dominic O'Grady a girl from the bush done good. The University of Sydney, Publications Office Room K6.06, Main Quadrangle A14, NSW 2006 18 DEAD MEDIA Telephone +61 2 9036 6372 Fax +61 2 9351 6868 The death of each media format not only alters Email [email protected] the way we communicate, but changes the way Sub-editor John Warburton we think. Design tania edwards design Contributors Gregory Baldwin, Tracey Beck, Vice-Chancellor Professor Gavin Brown, Graham Croker, regulars Jeff Hargrave, Stephanie Lee, Rodney Molesworth, Maggie Renvoize, Chris Rodley, Ted Sealy, Melissa Sweet, 4 OPINION Margaret Simons. International research hubs are the way of the future. Printed by Offset Alpine Printing on 55% recycled fibre. Offset Alpine is accredited with ISO 14001 for environ- 6 NEWS mental management, and only uses paper approved by Alumnus becomes Reserve Bank Governor. the Forest Stewardship Council. 8 RESEARCH: THE GENDER SELECTOR Cover illustration Gregory Baldwin. New sperm-sorting technology will make gender Advertising Please direct all inquiries to the editor. selection a commercial reality. Editorial Advisory Committe 23 NOW SHOWING The Sydney Alumni Magazine is supported by an Editorial Seymour Centre hosts theatre with bite. Advisory Committee. Its members are: Kathy Bail, Associate Editor, The Bulletin; Martin Hoffman (BEcon '86), consultant; 26 SPORT Helen Trinca, Editor, Boss (Australian Financial Review); Macquarie Bank’s David Clarke lends a hand. -

Chau Chak Wing Museum, the University of Sydney SSD 7894

STATE SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENT ASSESSMENT REPORT: Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney SSD 7894 Environmental Assessment Report Section 89H of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 February 2018 ABBREVIATIONS Applicant The University of Sydney, or anyone else entitled to act on this consent AS Australian Standard CBD Central Business District CIV Capital Investment Value Consent Development Consent Council City of Sydney DA Development Application DCP Development Control Plan Department Department of Planning and Environment EIS Environmental Impact Statement EPA Environment Protection Authority EP&A Act Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 EP&A Regulation Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulation 2000 EPI Environmental Planning Instrument ESD Ecologically Sustainable Development GANSW Government Architect New South Wales GFA Gross floor area HI Health Infrastructure ICNG Interim Construction Noise Guideline INP Industrial Noise Policy LEP Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 LGA Local Government Area LOS Level of Service Minister Minister for Planning NCC National Construction Code OEH Office of Environment and Heritage RMS Roads and Maritime Services RtS Response to Submissions SEARs Secretary’s Environmental Assessment Requirements Secretary Secretary of the Department of Planning and Environment SEPP State Environmental Planning Policy SRD SEPP State Environmental Planning Policy (State and Regional Development) 2011 SSD State Significant Development STP Sustainable Travel Plan TfNSW Transport