Thomas Fisher and the Fisher Bequest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scottish Background of the Sydney Publishing and Bookselling

NOT MUCH ORIGINALITY ABOUT US: SCOTTISH INFLUENCES ON THE ANGUS & ROBERTSON BACKLIST Caroline Viera Jones he Scottish background of the Sydney publishing and bookselling firm of TAngus & Robertson influenced the choice of books sold in their bookshops, the kind of manuscripts commissioned and the way in which these texts were edited. David Angus and George Robertson brought fi'om Scotland an emphasis on recognising and fostering a quality homegrown product whilst keeping abreast of the London tradition. This prompted them to publish Australian authors as well as to appreciate a British literary canon and to supply titles from it. Indeed, whilst embracing his new homeland, George Robertson's backlist of sentimental nationalistic texts was partly grounded in the novels and verse written and compiled by Sir Walter Scott, Robert Bums and the border balladists. Although their backlist was eclectic, the strong Scottish tradition of publishing literary journals, encyclopaedias and religious titles led Angus & Robertson, 'as a Scotch firm' to produce numerous titles for the Presbyterian Church, two volumes of the Australian Encyclopaedia and to commission writers from journals such as the Bulletin. 1 As agent to the public and university libraries, bookseller, publisher and Book Club owner, the firm was influential in selecting primary sources for the colony of New South Wales, supplying reading material for its Public Library and fulfilling the public's educational and literary needs. 2 The books which the firm published for the See Rebecca Wiley, 'Reminiscences of George Robertson and Angus & Robertson Ltd., 1894-1938' ( 1945), unpublished manuscript, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ML MSS 5238. -

Guide to the Christopher Brennan Collection

RARE BOOKS & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS University Library GUIDE TO THE CHRISTOPHER BRENNAN COLLECTION DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Collection Number: RB017 Collection Dates: 1887 - 1976 Title: Christopher Brennan Collection Creator: E.L. Hadley and M. Delmer Languages Represented: English, French, Latin Extent: 2 boxes Repository: University of Sydney Library, Rare Books and Special Collections Abstract: Christopher Brennan (1870-1932) was an Australian poet and scholar. He was a graduate of the University of Sydney (philosophy and classics) and studied at the University of Berlin from 1892-94. After discovering the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé he returned to Australia to devote the next ten years of his life to poetry, in which he explored the theme of the search for Eden. He worked at the Public Library of New South Wales from 1895 to 1907. He was appointed lecturer in French and German at the University of Sydney in 1909. From 1920 to 1925 he was associate professor in German and Comparative Literature. The Christopher Brennan Collection contains correspondence, part of a proof copy of Brennan's poems (1913), lecture notes, books, newspaper cuttings and etchings. ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Provenance Purchased from and donated by Miss E.L. Hadley and Miss M. Delmer. Miss Esme Hadley (died 1970) studied at the University of Sydney, graduating in 1914 with a BA Honours in French and German. It was during her time at the university that she met Christopher Brennan. During the 1930s she studied in Germany where she saw Hitler's first rally and attended the Berlin Olympic Games. She taught at Sydney Girls High from 1933 - 37 and from 1945 to her retirement in 1956. -

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey 43-51 Cowper Wharf Road September 2013 Woolloomooloo NSW 2011 w: www.mgnsw.org.au t: 61 2 9358 1760 Introduction • This report is presented in two parts: The 2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and the 2013 NSW Small to Medium Museum & Gallery Survey. • The data for both studies was collected in the period February to May 2013. • This report presents the first comprehensive survey of the small to medium museum & gallery sector undertaken by Museums & Galleries NSW since 2008 • It is also the first comprehensive census of the museum & gallery sector undertaken since 1999. Images used by permission. Cover images L to R Glasshouse, Port Macquarie; Eden Killer Whale Museum , Eden; Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, Bathurst; Lighting Ridge Museum Lightning Ridge; Hawkesbury Gallery, Windsor; Newcastle Museum , Newcastle; Bathurst Regional Gallery, Bathurst; Campbelltown arts Centre, Campbelltown, Armidale Aboriginal Keeping place and Cultural Centre, Armidale; Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington; Australian Country Music Hall of Fame, Tamworth; Powerhouse Museum, Tamworth 2 Table of contents Background 5 Objectives 6 Methodology 7 Definitions 9 2013 Museums and Gallery Sector Census Background 13 Results 15 Catergorisation by Practice 17 2013 Small to Medium Museums & Gallery Sector Survey Executive Summary 21 Results 27 Conclusions 75 Appendices 81 3 Acknowledgements Museums & Galleries NSW (M&G NSW) would like to acknowledge and thank: • The organisations and individuals -

Marjorie Barnard: a Re-Examination of Her Life and Work

Marjorie Barnard: a re-examination of her life and work June Owen A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales Australia School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Science Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Australia's Global UNSWSYDNEY University Surname/Family Name OWEN Given Name/s June Valerie Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar PhD Faculty Arts and Social Sciences School School of the Arts and Media Thesis Title Marjorie Barnard: a re-examination of her life and work Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) A wealth of scholarly works were written about Marjorie Barnard following the acclaim greeting the republication, in 1973, of The Persimmon Tree. That same year Louise E Rorabacher wrote a book-length study - Marjorie Barnard and M Barnard Eldershaw, after agreeing not to write about Barnard's private life. This led to many studies of the pair's joint literary output and short biographical studies and much misinformation, from scholars beguiled into believing Barnard's stories which were often deliberately disseminated to protect the secrecy of the affair that dominated her life between 1934 and 1942. A re-examination of her life and work is now necessary because there have been huge misunderstandings about other aspects of Barnard's life, too. Her habit of telling imaginary stories denigrating her father, led to him being maligned by his daughter's interviewers. Marjorie's commonest accusation was of her father's meanness, starting with her student allowance, but if the changing value of money is taken into account, her allowance (for pocket money) was extremely generous compared to wages of the time. -

Graham Clifton Southwell

Graham Clifton Southwell A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Department of Art History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2018 Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney A Hidden Artistic, Literary and Symbolic Treasure Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction and Literature Review Chapter Two: The Invention of Printing in Europe and Printers’ Marks Chapter Three: Mitchell Library Building 1906 until 1987 Chapter Four: Construction of the Bronze Southern Entrance Doors Chapter Five: Conclusion Bibliography i! Abstract Title: Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney. The building of the major part of the Mitchell Library (1939 - 1942) resulted in four pairs of bronze entrance doors, three on the northern facade and one on the southern facade. The three pairs on the northern facade of the library are obvious to everyone entering the library from Shakespeare Place and are well documented. However very little has been written on the pair on the southern facade apart from brief mentions in two books of the State Library buildings, so few people know of their existence. Sadly the excellent bronze doors on the southern facade of the library cannot readily be opened and are largely hidden from view due to the 1987 construction of the Glass House skylight between the newly built main wing of the State Library of New South Wales and the Mitchell Library. These doors consist of six square panels featuring bas-reliefs of different early printers’ marks and two rectangular panels at the bottom with New South Wales wildflowers. -

Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656

The University of Sydney Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 Faculty of Law Handbook 1995 ©The University of Sydney 1994 ISSN 1034-2656 The address of the Law School is: The University of Sydney Law School 173-5 Phillip Street Sydney, N.S.W. 2000 Telephone (02) 232 5944 Document Exchange No: DX 983 Facsimile: (02) 221 5635 The address of the University is: The University of Sydney N.S.W. 2006 Telephone 351 2222 Setin 10 on 11.5 Palatino by the Publications Unit, The University of Sydney and printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, Sydney. Text printed on 80gsm recycled bond, using recycled milk cartons. Welcome from the Dean iv Location of the Law School vi How to use the handbook vii 1. Staff 1 2. History of the Faculty of Law 3 3. Law courses 4 4. Undergraduate degree requirements 7 Resolutions of the Senate and the Faculty 7 5. Courses of study 12 6. Guide for law students and other Faculty information 24 The Law School Building 24 Guide for law students 24 Other Faculty information 29 Law Library 29 Sydney Law School Foundation 30 Sydney Law Review 30 Australian Centre for Environmental Law 30 Institute of Criminology 31 Centre for Plain Legal Language 31 Centre for Asian and Pacific Law 31 Faculty societies and student representation 32 Semester and vacation dates 33 The Allen Allen and Hemsley Visiting Fellowship 33 Undergraduate scholarships and prizes 34 7. Employment 36 Main Campus map 39 The legal profession in each jurisdiction was almost entirely self-regulating (and there was no doubt it was a profession, and not a mere 'occupation' or 'service industry'). -

Ii: Mary Alice Evatt, Modern Art and the National Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cultivating the Arts Page 394 CHAPTER 9 - WAGING WAR ON THE ESTABLISHMENT? II: MARY ALICE EVATT, MODERN ART AND THE NATIONAL ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES The basic details concerning Mary Alice Evatt's patronage of modern art have been documented. While she was the first woman appointed as a member of the board of trustees of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, the rest of her story does not immediately suggest continuity between her cultural interests and those of women who displayed neither modernist nor radical inclinations; who, for example, manned charity- style committees in the name of music or the theatre. The wife of the prominent judge and Labor politician, Bert Evatt, Mary Alice studied at the modernist Sydney Crowley-Fizelle and Melbourne Bell-Shore schools during the 1930s. Later, she studied in Paris under Andre Lhote. Her husband shared her interest in art, particularly modern art, and opened the first exhibition of the Contemporary Art Society in Melbourne 1939, and an exhibition in Sydney in the same year. His brother, Clive Evatt, as the New South Wales Minister for Education, appointed Mary Alice to the Board of Trustees in 1943. As a trustee she played a role in the selection of Dobell's portrait of Joshua Smith for the 1943 Archibald Prize. Two stories thus merge to obscure further analysis of Mary Alice Evatt's contribution to the artistic life of the two cities: the artistic confrontation between modernist and anti- modernist forces; and the political career of her husband, particularly knowledge of his later role as leader of the Labor opposition to Robert Menzies' Liberal Party. -

Camperdown and Darlington Campuses

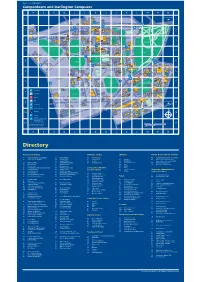

Map Code: 0102_MAIN Camperdown and Darlington Campuses A BCDEFGHJKLMNO To Central Station Margaret 1 ARUNDEL STREETTelfer Laurel Tree 1 Building House ROSS STREETNo.1-3 KERRIDGE PLACE Ross Mackie ARUNDEL STREET WAY Street Selle Building BROAD House ROAD Footbridge UNIVERSITY PARRAMATTA AVENUE GATE LARKIN Theatre Edgeworth Botany LANE Baxter's 2 David Lawn Lodge 2 Medical Building Macleay Building Foundation J.R.A. McMillan STREET ROSS STREET Heydon-Laurence Holme Building Fisher Tennis Building Building GOSPER GATE AVENUE SPARKES Building Cottage Courts STREET R.D. Watt ROAD Great Hall Ross St. Building Building SCIENCE W Gate- LN AGRICULTURE EL Bank E O Information keepers S RUSSELL PLACE R McMaster Building P T Centre UNIVERSITY H Lodge Building J.D. E A R Wallace S Badham N I N Stewart AV Pharmacy E X S N Theatre Building E U ITI TUNN E Building V A Building S Round I E C R The H Evelyn D N 3 OO House ROAD 3 D L L O Quadrangle C A PLAC Williams Veterinary John Woolley S RE T King George VI GRAFF N EK N ERSITY Building Science E Building I LA ROA K TECHNOLOGY LANE N M Swimming Pool Conference I L E I Fisher G Brennan MacCallum F Griffith Taylor UNIV E Centre W Library R Building Building McMaster Annexe MacLaurin BARF University Oval MANNING ROAD Hall CITY R.M.C. Gunn No.2 Building Education St. John's Oval Old Building G ROAD Fisher Teachers' MANNIN Stack 4 College Manning 4 House Manning Education Squash Anderson Stuart Victoria Park H.K. -

Sf Commentary 76

SF COMMENTARY 76 30TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION October 2000 THE UNRELENTING GAZE GEORGE TURNER’S NON-FICTION: A SELECTION SF COMMENTARY No. 76 THIRTIETH ANNIVERSARY EDITION OCTOBER 2000 THE UNRELENTING GAZE GEORGE TURNER’S NON-FICTION: A SELECTION COVER GRAPHICS Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Introductions 3 GEORGE TURNER: THE UNRELENTING GAZE Bruce Gillespie 4 GEORGE TURNER: CRITIC AND NOVELIST John Foyster 6 NOT TAKING IT ALL TOO SERIOUSLY: THE PROFESSION OF SCIENCE FICTION No. 27 12 SOME UNRECEIVED WISDOM Famous First Words 16 THE DOUBLE STANDARD: THE SHORT LOOK, AND THE LONG HARD LOOK 20 ON WRITING ABOUT SCIENCE FICTION 25 The Reviews 31 GOLDEN AGE, PAPER AGE or, WHERE DID ALL THE CLASSICS GO? 34 JOHN W. CAMPBELL: WRITER, EDITOR, LEGEND 38 BACK TO THE CACTUS: THE CURRENT SCENE, 1970 George and Australian Science Fiction 45 SCIENCE FICTION IN AUSTRALIA: A SURVEY 1892–1980 George’s Favourite SF Writers URSULA K. LE GUIN: 56 PARADIGM AND PATTERN: FORM AND MEANING IN ‘THE DISPOSSESSED’ 64 FROM PARIS TO ANARRES: ‘The Wind’s Twelve Quarters’ THOMAS M. DISCH: 67 TOMORROW IS STILL WITH US: ‘334’ 70 THE BEST SHORT STORIES OF THOMAS M. DISCH GENE WOLFE: 71 TRAPS: ‘The Fifth Head of Cerberus’ 73 THE REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PRESENT: ‘Peace’ George Disagrees . 76 FREDERIK POHL AS A CREATOR OF FUTURE SOCIETIES 85 PHILIP K. DICK: BRILLIANCE, SLAPDASH AND SLIPSHOD: ‘Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said’ 89 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR: ‘New Dimensions I’ 93 PLUMBERS OF THE COSMOS: THE AUSSIECON DEBATE Peter Nicholls and George Turner George and the Community of Writers 100 A MURMURATION OF STARLING OR AN EXALTATION OF LARK?: 1977 Monash Writers’ Workshop Illustrations by Chris Johnston 107 GLIMPSES OF THE GREAT: SEACON (WORLD CONVENTION, BRIGHTON) AND GLASGOW, 1979 George Tells A Bit About Himself 111 HOME SWEET HOME: HOW I MET MELBA 114 JUDITH BUCKRICH IN CONVERSATION WITH GEORGE TURNER: The Last Interview 2 SF COMMENTARY, No. -

5-7 December, Sydney, Australia

IRUG 13 5-7 December, Sydney, Australia 25 Years Supporting Cultural Heritage Science This conference is proudly funded by the NSW Government in association with ThermoFisher Scientific; Renishaw PLC; Sydney Analytical Vibrational Spectroscopy Core Research Facility, The University of Sydney; Agilent Technologies Australia Pty Ltd; Bruker Pty Ltd, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences; and the John Morris Group. Conference Committee • Paula Dredge, Conference Convenor, Art Gallery of NSW • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Boris Pretzel, (IRUG Chair for Europe & Africa), Victoria and Albert Museum, London • Beth Price, (IRUG Chair for North & South America), Philadelphia Museum of Art Scientific Review Committee • Marcello Picollo, (IRUG chair for Asia, Australia & Oceania) Institute of Applied Physics “Nello Carrara” Sesto Fiorentino, Italy • Danilo Bersani, University of Parma, Parma, Italy • Elizabeth Carter, Sydney Analytical, The University of Sydney, Australia • Silvia Centeno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA • Wim Fremout, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels, Belgium • Suzanne de Grout, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, The Netherlands • Kate Helwig, Canadian Conservation Institute, Ottawa, Canada • Suzanne Lomax, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA • Richard Newman, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA • Gillian Osmond, Queensland Art Gallery|Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia • Catherine Patterson, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, USA -

SL MAGAZINE Winter 2018 State Library of New South Wales NEWS

–Winter 2018 Vanessa Berry goes underground Message Since I last wrote to you, the Library has lost one of its greatest friends and supporters. You can read more about Michael Crouch’s life in this issue. For my part, I salute a friend, a man of many parts, and a philanthropist in the truest sense of the word — a lover of humanity. Together with John B Fairfax, Sam Meers, Rob Thomas, Kim Williams and many others, he has been the enabling force behind the transformation currently underway at the Library. Roll on October, when we can show you what the fuss is about. Our great Library, as it stands today, is the result of nearly 200 years of public and private partnerships. It is one of the NSW Government’s most precious assets, but much of what we do today would be impossible without additional private support. The new galleries in the Mitchell Building are only one example of this. Our Foundation is currently supporting many other projects, including Caroline Baum’s inaugural Readership in Residence, our DX Lab Fellow Thomas Wing-Evans’ ground-breaking work, the Far Out! educational outreach program, the National Biography Award, the Sydney Harbour Bridge online exhibition (currently in preparation), not to mention the preservation and preparation of our oil paintings for the major hang later this year. All successful institutions need to have a clear idea of what they stand for if they are to continue to attract support from both government and private benefactors. At the first ‘Dinner with the State Librarian’ on 12 April, I addressed an audience of more than 100 supporters about the Library in its long-term historical context — stressing the importance of preserving both oral and written traditions in our collections and touching on the history we share with museums. -

Creative Foundations. the Royal Society of New South Wales: 1867 and 2017

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 150, part 2, 2017, pp. 232–245. ISSN 0035-9173/17/020232-14 Creative foundations. The Royal Society of New South Wales: 1867 and 2017 Ann Moyal Emeritus Fellowship, ANU, Canberra, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract There have been two key foundations in the history of the Royal Society of New South Wales. The first at its creation as a Royal Society in 1867, shaped significantly by the Colonial savant, geologist the Rev. W. B. Clarke, assisted by a corps of pioneering scientists concerned to develop practical sci- entific knowledge in the colony of N.S.W. And the second, under the guidance of President Donald Hector 2012–2016 and his counsellors, fostering a vital “renaissance” in the Society’s affairs to bring the high expertise of contemporary scientific and transdisciplinary members to confront the complex socio-techno-economic problems of a challenging twenty-first century. his country is so dead to all that natures) on a span of topics that embraced “Tconcerns the life of the mind”, the geology, meteorology, climate, mineralogy, scholarly newcomer the Rev. W. B. Clarke the natural sciences, earthquakes, volcanoes, wrote to his mother in England in Septem- comets, storms, inland and maritime explo- ber 1839 shortly after his arrival in New ration and its discoveries which gave singular South Wales (Moyal, 2003, p. 10). But a impetus to the newspaper’s role as a media man with a future, he quickly took up the pioneer in the communication of science offer of the editor ofThe Sydney Herald, John (Organ, 1992).