Seas at the Millenium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i: Nā Makani

November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai‘i: Nā Makani Mau Steven Businger & Sara da Silva [email protected], [email protected] Iasona Ellinwood, [email protected] Pauline W. U. Chinn, [email protected] University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Figure 1. Schematic of global circulation Grades: 6-8, modifiable for 9-12 Time: 2 - 10 hours Nā Honua Mauli Ola, Guidelines for Educators, No Nā Kumu: Educators are able to sustain respect for the integrity of one’s own cultural knowledge and provide meaningful opportunities to make new connections among other knowledge systems (p. 37). Standard: Earth and Space Science 2.D ESS2D: Weather and Climate Weather varies day to day and seasonally; it is the condition of the atmosphere at a given place and time. Climate is the range of a region’s weather over one to many years. Both are shaped by complex interactions involving sunlight, ocean, atmosphere, latitude, altitude, ice, living things, and geography that can drive changes over multiple time scales—days, weeks, and months for weather to years, decades, centuries, and beyond for climate. The ocean absorbs and stores large amounts of energy from the sun and releases it slowly, moderating and stabilizing global climates. Sunlight heats the land more rapidly. Heat energy is redistributed through ocean currents and atmospheric circulation, winds. Greenhouse gases absorb and retain the energy radiated from land and ocean surfaces, regulating temperatures and keep Earth habitable. (A Framework for K-12 Science Education, NRC, 2012) Hawai‘i Content and Performance Standards (HCPS) III http://standardstoolkit.k12.hi.us/index.html 1 November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i STRAND THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS Standard 1: The Scientific Process: SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION: Discover, invent, and investigate using the skills necessary to engage in the scientific process Benchmarks: SC.8.1.1 Determine the link(s) between evidence and the Topic: Scientific Inquiry conclusion(s) of an investigation. -

Estimation of Significant Wave Height Using Satellite Data

Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 4(24): 5332-5338, 2012 ISSN: 2040-7467 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2012 Submitted: March 18, 2012 Accepted: April 23, 2012 Published: December 15, 2012 Estimation of Significant Wave Height Using Satellite Data R.D. Sathiya and V. Vaithiyanathan School of Computing, SASTRA University, Thirumalaisamudram, India Abstract: Among the different ocean physical parameters applied in the hydrographic studies, sufficient work has not been noticed in the existing research. So it is planned to evaluate the wave height from the satellite sensors (OceanSAT 1, 2 data) without the influence of tide. The model was developed with the comparison of the actual data of maximum height of water level which we have collected for 24 h in beach. The same correlated with the derived data from the earlier satellite imagery. To get the result of the significant wave height, beach profile was alone taking into account the height of the ocean swell, the wave height was deduced from the tide chart. For defining the relationship between the wave height and the tides a large amount of good quality of data for a significant period is required. Radar scatterometers are also able to provide sea surface wind speed and the direction of accuracy. Aim of this study is to give the relationship between the height, tides and speed of the wind, such relationship can be useful in preparing a wave table, which will be of immense value for mariners. Therefore, the relationship between significant wave height and the radar backscattering cross section has been evaluated with back propagation neural network algorithm. -

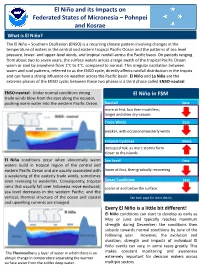

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

Deep Ocean Wind Waves Ch

Deep Ocean Wind Waves Ch. 1 Waves, Tides and Shallow-Water Processes: J. Wright, A. Colling, & D. Park: Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford UK, 1999, 2nd Edition, 227 pp. AdOc 4060/5060 Spring 2013 Types of Waves Classifiers •Disturbing force •Restoring force •Type of wave •Wavelength •Period •Frequency Waves transmit energy, not mass, across ocean surfaces. Wave behavior depends on a wave’s size and water depth. Wind waves: energy is transferred from wind to water. Waves can change direction by refraction and diffraction, can interfere with one another, & reflect from solid objects. Orbital waves are a type of progressive wave: i.e. waves of moving energy traveling in one direction along a surface, where particles of water move in closed circles as the wave passes. Free waves move independently of the generating force: wind waves. In forced waves the disturbing force is applied continuously: tides Parts of an ocean wave •Crest •Trough •Wave height (H) •Wavelength (L) •Wave speed (c) •Still water level •Orbital motion •Frequency f = 1/T •Period T=L/c Water molecules in the crest of the wave •Depth of wave base = move in the same direction as the wave, ½L, from still water but molecules in the trough move in the •Wave steepness =H/L opposite direction. 1 • If wave steepness > /7, the wave breaks Group Velocity against Phase Velocity = Cg<<Cp Factors Affecting Wind Wave Development •Waves originate in a “sea”area •A fully developed sea is the maximum height of waves produced by conditions of wind speed, duration, and fetch •Swell are waves -

Swell and Wave Forecasting

Lecture 24 Part II Swell and Wave Forecasting 29 Swell and Wave Forecasting • Motivation • Terminology • Wave Formation • Wave Decay • Wave Refraction • Shoaling • Rouge Waves 30 Motivation • In Hawaii, surf is the number one weather-related killer. More lives are lost to surf-related accidents every year in Hawaii than another weather event. • Between 1993 to 1997, 238 ocean drownings occurred and 473 people were hospitalized for ocean-related spine injuries, with 77 directly caused by breaking waves. 31 Going for an Unintended Swim? Lulls: Between sets, lulls in the waves can draw inexperienced people to their deaths. 32 Motivation Surf is the number one weather-related killer in Hawaii. 33 Motivation - Marine Safety Surf's up! Heavy surf on the Columbia River bar tests a Coast Guard vessel approaching the mouth of the Columbia River. 34 Sharks Cove Oahu 35 Giant Waves Peggotty Beach, Massachusetts February 9, 1978 36 Categories of Waves at Sea Wave Type: Restoring Force: Capillary waves Surface Tension Wavelets Surface Tension & Gravity Chop Gravity Swell Gravity Tides Gravity and Earth’s rotation 37 Ocean Waves Terminology Wavelength - L - the horizontal distance from crest to crest. Wave height - the vertical distance from crest to trough. Wave period - the time between one crest and the next crest. Wave frequency - the number of crests passing by a certain point in a certain amount of time. Wave speed - the rate of movement of the wave form. C = L/T 38 Wave Spectra Wave spectra as a function of wave period 39 Open Ocean – Deep Water Waves • Orbits largest at sea sfc. -

Statistics of Extreme Waves in Coastal Waters: Large Scale Experiments and Advanced Numerical Simulations

fluids Article Statistics of Extreme Waves in Coastal Waters: Large Scale Experiments and Advanced Numerical Simulations Jie Zhang 1,2, Michel Benoit 1,2,* , Olivier Kimmoun 1,2, Amin Chabchoub 3,4 and Hung-Chu Hsu 5 1 École Centrale Marseille, 13013 Marseille, France; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (O.K.) 2 Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS, Centrale Marseille, IRPHE UMR 7342, 13013 Marseille, France 3 Centre for Wind, Waves and Water, School of Civil Engineering, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] 4 Marine Studies Institute, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 5 Department of Marine Environment and Engineering, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 80424, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 February 2019; Accepted: 20 May 2019; Published: 29 May 2019 Abstract: The formation mechanism of extreme waves in the coastal areas is still an open contemporary problem in fluid mechanics and ocean engineering. Previous studies have shown that the transition of water depth from a deeper to a shallower zone increases the occurrence probability of large waves. Indeed, more efforts are required to improve the understanding of extreme wave statistics variations in such conditions. To achieve this goal, large scale experiments of unidirectional irregular waves propagating over a variable bottom profile considering different transition water depths were performed. The validation of two highly nonlinear numerical models was performed for one representative case. The collected data were examined and interpreted by using spectral or bispectral analysis as well as statistical analysis. -

The Wind-Wave Climate of the Pacific Ocean

The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research A partnership between CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology The wind-wave climate of the Pacific Ocean. Mark Hemer, Jack Katzfey and Claire Hotan Final Report 30 September 2011 Report for the Pacific Adaptation Strategy Assistance Program Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency [Insert ISBN or ISSN and Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) information here if required] Enquiries should be addressed to: Mark Hemer Email. [email protected] Distribution list DCCEE 1 Copyright and Disclaimer © 2011 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important Disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. Contents -

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Yap And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Yap and Chuuk What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then very much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones Less reduced risk, as more storms form closer to the Dateline El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

Tropical Cyclone Part II (1+1+1 System) Geography Hons

Tropical Cyclone Part II (1+1+1 System) Geography Hons. Paper: IV Module: V Topic: 4.1 A tropical cyclone is a system of the low pressure area surrounded by high pressure areas on all sides occurring in tropical zone bound by Tropic of Cancer in the north and Tropic of Capricorn in the south. Chief Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones 1. Tropical cyclones are of numerous forms which vary considerably in shape, size and weather conditions. 2. There are wide variations in the size of the tropical cyclones. However, the average diameter of a tropical cyclone varies from 80 to 300 km. Some of the cyclones have diameter of only 50 km or even less than that. 3. The isobars in most tropical cyclones are generally circular, indicating that most of the tropical cyclones are circular in shape. 4. The isobars are closely spaced which indicates that the pressure gradient is very steep and winds blow at high speed. 5. Most of the tropical cyclones originate on the western margins of the oceans where warm ocean currents maintain sea surface temperature above 27°C. 6. They advance with varying velocities and their velocities depend upon a number of factors. Weak cyclones move at velocities varying from 30 to 35 km/hr. while hurricanes may attain velocity of 180 km/hr. or even more. 7. They are very vigorous and move with high speed over the oceans where there are no obstructions in their way. 8. They are more frequent in late summer and autumn in the Northern Hemisphere and spring in the Southern Hemisphere. -

Random Wave Analysis

RANDOM WA VE ANALYSIS The goal of this handout is to consider statistical and probabilistic descriptions of random wave heights and periods. In design, random waves are often represented by a single characteristic wave height and wave period. Most often, the significant wave height is used to represent wave heights in a random sea. It is important to understand, however, that wave heights have some statistical variability about this representative value. Knowledge of the probability distribution of wave heights is therefore essential to fully describe the range of wave conditions expected, especially the extreme values that are most important for design. Short Term Statistics of Sea Waves: Short term statistics describe the probabilities of qccurrence of wave heights and periods that occur within one observation or measurement of ocean waves. Such an observation typically consists of a wave record over a short time period, ranging from a few minutes to perhaps 15 or 30 minutes. An example is shown below in Figure 1 for a 150 second wave record. @. ,; 3 <D@ Q) Q ® ®<V®®®@@@ (fJI@ .~ ; 2 "' "' ~" '- U)" 150 ~ -Il. Time.I (s) ;:::" -2 Figure 1. Example of short term wave record from a random sea (Goda, 2002) . ' Zero-Crossing Analysis The standard. method of determining the short-term statistics of a wave record is through the zero-crossing analysis. Either the so-called zero-upcrossing method or the zero downcrossing method may be used; the statistics should be the same for a sufficiently long record. Figure 1 shows the results from a zero-upcrossing analysis. In this case, the mean water level is first determined. -

Storm, Rogue Wave, Or Tsunami Origin for Megaclast Deposits in Western

Storm, rogue wave, or tsunami origin for megaclast PNAS PLUS deposits in western Ireland and North Island, New Zealand? John F. Deweya,1 and Paul D. Ryanb,1 aUniversity College, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 4BH, United Kingdom; and bSchool of Natural Science, Earth and Ocean Sciences, National University of Ireland Galway, Galway H91 TK33, Ireland Contributed by John F. Dewey, October 15, 2017 (sent for review July 26, 2017; reviewed by Sarah Boulton and James Goff) The origins of boulderite deposits are investigated with reference wavelength (100–200 m), traveling from 10 kph to 90 kph, with to the present-day foreshore of Annagh Head, NW Ireland, and the multiple back and forth actions in a short space and brief timeframe. Lower Miocene Matheson Formation, New Zealand, to resolve Momentum of laterally displaced water masses may be a contributing disputes on their origin and to contrast and compare the deposits factor in increasing speed, plucking power, and run-up for tsunamis of tsunamis and storms. Field data indicate that the Matheson generated by earthquakes with a horizontal component of displace- Formation, which contains boulders in excess of 140 tonnes, was ment (5), for lateral volcanic megablasts, or by the lateral movement produced by a 12- to 13-m-high tsunami with a period in the order of submarine slide sheets. In storm waves, momentum is always im- of 1 h. The origin of the boulders at Annagh Head, which exceed portant(1cubicmeterofseawaterweighsjustover1tonne)in 50 tonnes, is disputed. We combine oceanographic, historical, throwing walls of water continually at a coastline. -

Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania

13 · Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania BEN FINNEY MENTAL CARTOGRAPHY formal images and their own sense perceptions to guide their canoes over the ocean. The navigational practices of Oceanians present some The idea of physically portraying their mental images what of a puzzle to the student of the history of carto was not alien to these specialists, however. Early Western graphy. Here were superb navigators who sailed their ca explorers and missionaries recorded instances of how in noes from island to island, spending days or sometimes digenous navigators, when questioned about the islands many weeks out of sight of land, and who found their surrounding their own, readily produced maps by tracing way without consulting any instruments or charts at sea. lines in the sand or arranging pieces of coral. Some of Instead, they carried in their head images of the spread of these early visitors drew up charts based on such ephem islands over the ocean and envisioned in the mind's eye eral maps or from information their informants supplied the bearings from one to the other in terms of a con by word and gesture on the bearing and distance to the ceptual compass whose points were typically delineated islands they knew. according to the rising and setting of key stars and con Furthermore, on some islands master navigators taught stellations or the directions from which named winds their pupils a conceptual "star compass" by laying out blow. Within this mental framework of islands and bear coral fragments to signify the rising and setting points of ings, to guide their canoes to destinations lying over the key stars and constellations.