Scaling up Programs to Reduce Human Rights- Related Barriers to HIV and TB Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allocution De Premier Ministre Amadou Gon Coulibaly

CABINET DU PREMIER MINISTRE REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE CHEF DU GOUVERNEMENT Union – Discipline – Travail ----------------- ---------------------- JOURNEE DE RECONNAISSANCE, D’HOMMAGE ET DE SOUTIEN DE LA REGION DU GÔH AU PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE Discours de Monsieur Amadou Gon COULIBALY, Premier Ministre, Chef du Gouvernement, Ministre du Budget et du Portefeuille de l’Etat Gagnoa, le 12 janvier 2019 1 Je suis particulièrement heureux de me retrouver de nouveau à Gagnoa, la capitale régionale du Gôh, villeau passé glorieux, villechargée d’histoire et de symboles de notre pays. Je voudrais saluer cette autre grande et belle mobilisation de ce jour,qui devraitconvaincre les plussceptiques du soutien résolu et indéfectible des populations du Gôh au Président de la République, SEM Alassane Ouattara. Monsieur le Président du Conseil Régional du Gôh, Parce que vous incarnezla fidélité et le travail bien fait, le Président de la République a décidé de récompenser votre dévouement au service de l’Etat, en vous nommant à la tête du Conseil d’Administration d’un important outil de développement, le Fonds d’Entretien Routier. 0 Je voudrais donc vousféliciter chaleureusement pour la confiance que le Président de la République, S.E.M. Alassane Ouattara ne cesse de vous témoigner. J’adresse également mes félicitationsappuyées à Mesdames lesSecrétaires d’Etat, AiméeZébéyoux et MyssBelmondeDogo, mes chères sœurs, qui font preuve d’un dévouement remarquable au gouvernement, et d’un engagement sans faille aux côtés du Président de la République. Auxélus, -

Cote D'ivoire Situation

SITUATIONAL EMERGENCY UPDATE Cote d’Ivoire Situation 12 November 2020 As of 11 November 2020, a total Nearly 92% of the new arrIvals who UNHCR has set up of 10,087 Ivorians have fled have fled Cote d’Ivoire are In LIberIa contingency plans in the Cote d’Ivoire, and the numbers where an airlIft of CRIs for 10,000 countrIes neIghbourIng Cote continue to rIse amid persIstent refugees is planned from DubaI. In the d’Ivoire and Is engaging wIth tensions despIte valIdation of the meantIme, locally purchased core- natIonal and local authorIties, electIon results by the relief items, food and cash-based sister UN agencies and other Constitutional Court. interventions are being delIvered. partners. POPULATION OF CONCERN Host Countries New arrivals LiberIa 9,255 Ghana 563 Guinea 249 Togo 20 Cote d’IvoIre (IDPs) 5,530 Total 15,617 * Data as of 11 November 2020 as reported by UNHCR Operations. New arrIvals at Bhai border, Grand Gedeh. CredIt @UNHCR www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Cote d’Ivoire Situation / November 2020 OperatIonal Context PolItIcal and securIty sItuatIon In Cote d’IvoIre Aftermath of the election ■ On 9 November, the ConstItutIonal CouncIl valIdated the electoral vIctory of PresIdent Alassane Ouattara as proclaimed by the Independent Electoral CommIssIon. The sItuatIon remaIns calm yet tense and the opposItIon, whIch announced the formatIon of a NatIonal TransItIonal CouncIl, has yet to recognIze the PresIdent’s vIctory. ■ FollowIng the valIdatIons of the electIon of PresIdent Ouattara, a Government spokesperson declared that a total of 85 people were kIlled, IncludIng 34 before the election, 20 on polling day, 31 after the election. -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions”

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions” Abstract Abidjan is the political capital of Ivory Coast. This five million people city is one of the economic motors of Western Africa, in a country whose democratic strength makes it an example to follow in sub-Saharan Africa. However, when disasters such as floods strike, their most vulnerable areas are observed and consequences such as displacements, economic desperation, and even public health issues occur. In this research, I looked at the problem of flooding in Abidjan by focusing on their institutional response. I analyzed its institutional resilience at three different levels: local, national, and international. A total of 20 questionnaires were completed by 20 different participants. Due to the places where the respondents lived or worked when the floods occurred, I focused on two out of the 10 communes of Abidjan after looking at the city as a whole: Macory (Southern Abidjan) and Cocody (Northern Abidjan). The goal was to talk to the Abidjan population to gather their thoughts from personal experiences and to look at the data published by these institutions. To analyze the information, I used methodology combining a qualitative analysis from the questionnaires and from secondary sources with a quantitative approach used to build a word-map with the platform Voyant, and a series of Arc GIS maps. The findings showed that the international organizations responded the most effectively to help citizens and that there is a general discontent with the current local administration. The conclusions also pointed out that government corruption and lack of infrastructural preparedness are two major problems affecting the overall resilience of Abidjan and Ivory Coast to face this shock. -

WANEP Rapport Avril 2013.Pdf

RAPPORT MENSUEL DE LA COLLECTE D’INFORMATIONS RELATIVES A LA SECURITE HUMAINE MOIS D’AVRIL 2013 PROGRAMME ALERTE PRECOCE ET PREVENTION DES CONFLITS HISTORIQUE SOMMAIRE Le WANEP-CI propose le douzième numéro de son rapport mensuel sur la Historique (CI-WARN) sécurité humaine qui est également le quatrième de l’année 2013. Situation générale Pour rappel, cette diffusion a pour objectif d’informer le public et surtout faire Faits saillants des recommandations afin de permettre aux décideurs d’apporter des réponses aux différents problèmes de la sécurité humaine en Côte d’Ivoire. Actions menées / mesures prises Recommandations I- SITUATION GENERALE La vie politique a été marquée par les élections couplées municipales et régionales du dimanche 21 avril 2013. Celles-ci ont été émaillées par endroits de violences provoquant B des dégâts. Â T Au plan social, les manifestations de protestation des enseignants de l’Intersyndicale du Secteur de l’Education-Formation (ISEF), entamées en mars, suite à la décision du gouvernement de faire une I R ponction sur les salaires du mois de Mars d’environ 50.000 enseignants, se sont poursuivies. Au plan économique, l’on enregistre la baisse du prix du Super sans plomb et la bouteille de gaz B28. D E S II- FAITS SAILLANTS C R 1- La situation sécuritaire E a- Attaques à mains à mains et autres I L A a-1 attaques à mains à mains - T I Le mardi 02 avril, près du stade Robert Champroux à Marcory (Abidjan), des hommes armés ont W O braqué un chauffeur d’une société spécialisée en production d'énergie. -

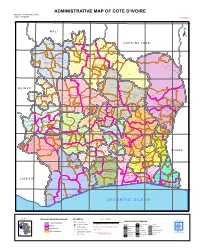

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

Economic and Climate Effects of Low-Carbon Agricultural And

ISSN 2521-7240 ISSN 2521-7240 7 7 Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire FAO AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS TECHNICAL STUDY DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS AGRICULTURAL FAO 7 Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire By Florent Eveillé Energy expert, Climate and Environment Division (CBC), FAO Laure-Sophie Schiettecatte Climate mitigation expert, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), FAO Anass Toudert Consultant, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA), FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 Required citation: Eveillé, F., Schiettecatte, L.-S. & Toudert, A. 2020. Economic and climate effects of low-carbon agricultural and bioenergy practices in the rice value chain in Gagnoa, Côte d’Ivoire. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study 7. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb0553en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Cote D'lvoire

Cote d’lvoire SIGNIFICANT ADVANCEMENT In 2014, Côte d’Ivoire made a significant advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The Government conducted a labor survey which included a subsurvey to determine the activities of working children; issued a decree to implement the Trafficking and Worst Forms of Child Labor Law that was adopted in 2010; and adopted a National Policy Document on Child Protection. The Government also established a National Committee for the Fight Against Trafficking in Persons; increased the budget of the Directorate for the Fight Against Child Labor by $800,000; continued to support social programs that address child labor in support of activities under the National Action Plan against Trafficking, Exploitation, and Child Labor (NAP); and completed the pilot phase of the child labor monitoring system known as SOSTECI. However, children in Côte d’Ivoire are engaged in the worst forms of child labor in domestic work and agriculture, particularly on cocoa farms, sometimes under conditions of forced labor. Gaps remain in enforcement efforts and in children’s access to education. I. PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR Children in Côte d’Ivoire are engaged in the worst forms of child labor in domestic work and agriculture, particularly on cocoa farms, sometimes under conditions of forced labor.(1-9) According to a report by Tulane University that assessed data collected during the 2013–2014 harvest season, there were an estimated 1,203,473 child laborers ages 5 to 17 in the cocoa sector, of which 95.9 percent were engaged in hazardous work in cocoa production.(10) Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in Côte d’Ivoire. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Pdf | 318.08 Kb

6° 5° 4° UNOCI Sikasso B Bobo Dioulasso CÔTE ag o D'IVOIRE 11° Deployment é Orodara lé Kadiana as of 18 Novuember 2004 o MALI Mandiana a B Manankoro BURKINA FASO Tingréla Gaoua i Sa an Niélé nk b é ar ia o ani nd ha m Wa a Wangolodougou o 10° M K Kouto 10° Samatigila BENIN (-) Batié é o g UNMO UNMO a GHANA (-) B UNMO Ferkessédougou UNMO Odienné Boundiali Korhogo Sirana Bouna Sawla Soukourala CÔTE D'IVOIRE GHANA Tafiré Bania Bolé Ba 9° nd Kokpingue a B 9 m o HQ Sector East GHANA ° GUINEA Morondo a u Niakaramandougou R MOROCCO (-) o Beyla u GHANA g Kani e PAKISTAN Dabakala GHANA (-) BANGLADESH (-) GHANA Nassian Touba MOROCCO (-) GHANA UNMO BANGLADESH (-) UNMO Katiola UNMO Bondoukou 8° NIGER Sandegue 8° Séguéla BANGLADESH MOROCCO BANGLADESH (-) Famienkro Tanda Sampa MOROCCO (-) Biankouma BANGLADESH Bouaké NIGER Prikro UNMO Fari M'Babo Adi- NIGER UNMO Zuénoula Yaprikro Berekum Man Djebonoua Koun-Fao Gohitafla FRANCE Mbahiakro Danané BAGLADESH MOROCCO NIGER (-) Kanzra Guezon PAKISTAN Yacouba- Bonoufla Bouaflé Daoukro Agnibilékrou 7 o N ° b Tiebissou 7 Carrefour UNMO z ° o Daloa i BANGLADESH BANGLADESH L Yamoussoukro y UNMO y b Goaso ll e a UNMO n v g a HQ Sector West Zambakro C Duékoué A GHANA UNOCI Abengourou Issia (-) HQ Toulépleu BANGLADESH a Guiglo i BANGLADESH Oumé TOGO Akoupé B BANGLADESH Nz HQ o BANGLADESH UNMO BANGLADESH o Zwedru BANGLADESH n a Gagnoa T 6° UNMO BANGLADESH 6° Taï Divo Agboville NIGER Soubré Lakota Enchi Tiassalé SecGr Pyne Town S GHANA a s s UNMO a n B Sikinssi d r o a u a b Aboisso o o m v a Bingerville LIBERIA a d -

(WQI): Case of the Ébrié Lagoon, Abidjan, Côte D'ivoire

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 January 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201801.0150.v1 1 Article 2 Spatio-Temporal analysis and Water Quality Indices 3 (WQI): case of the Ébrié Lagoon, Abidjan, Côte 4 d’Ivoire 5 Naga Coulibaly 1,*, Talnan Jean Honoré Coulibaly 1, Henoc Sosthène Aclohou 1, 6 Ziyanda Mpakama², Issiaka Savané 1 7 Laboratoire de Géosciences et Environnement, UFR des Sciences et gestion de l’Environnement, Université 8 NANGUI ABROGOUA, Abidjan; [email protected], [email protected], 9 [email protected], [email protected] 10 2 Programme Manager Africa Regional Centre | Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), Pretoria, 11 South Africa; [email protected] 12 * Correspondence: [email protected], Tel: +225-05-83-75-99 13 Abstract: For decades, the Ébrié Lagoon in Côte d'Ivoire has been the receptacle of wastewater 14 effluent and household waste transported by runoff water. This work assesses the spatio-temporal 15 variability of the Ébrié lagoon water quality at the city of Abidjan. The methodological approach 16 used in this study is summarized in three stages: the choice and standardization of the parameters 17 for assessing water quality for uses such as aquaculture, irrigation, watering, and sports and 18 recreation; the weighting of these parameters using the Hierarchical Analysis Process (AHP) of 19 Saaty; and finally, the aggregation of the weighted parameters or factors. Physicochemical and 20 microbiological analysis data on the waters of the Ébrié lagoon for June and December of 2014 and 21 2015 were provided by the Ivorian Center for Anti-Pollution (Centre Ivoirien Anti-Pollution, 22 CIAPOL) and the concentrations of trace elements in sediments (As, Cd, Cr, Pb, Zn) were used.