A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of the Electronic Monitoring of Offenders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Systematic Review Protocol for Crime Trends Facilitated by Synthetic Biology Mariam Elgabry1,2 , Darren Nesbeth2 and Shane D

Elgabry et al. Systematic Reviews (2020) 9:22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-1284-1 PROTOCOL Open Access A systematic review protocol for crime trends facilitated by synthetic biology Mariam Elgabry1,2 , Darren Nesbeth2 and Shane D. Johnson1* Abstract Background: When new technologies are developed, it is common for their crime and security implications to be overlooked or given inadequate attention, which can lead to a ‘crime harvest’. Potential methods for the criminal exploitation of biotechnology need to be understood to assess their impact, evaluate current policies and interventions and inform the allocation of limited resources efficiently. Recent studies have illustrated some of the security implications of biotechnology, with outcomes of misuse ranging from compromised computers using malware stored in synthesised DNA, infringement of intellectual property on biological matter, synthesis of new threatening viruses, ‘genetic genocide,’ and the exploitation of food markets with genetically modified crops. However, there exists no synthesis of this information, and no formal quality assessment of the current evidence. This review therefore aims to establish what current and/or predicted crimes have been reported as a result of biotechnology. Methods: A systematic review will be conducted to identify relevant literature. ProQuest, Web of Science, MEDLINE and USENIX will be searched utilizing a predefined search string, and Backward and Forward searches. Grey literature will be identified by searching the official UK Government website (www.gov.uk) and the Global database of Dissertations and Theses. The review will be conducted by screening title/abstracts followed by full texts, utilising pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers will be managed using Eppi-center Reviewer 4 software, and data will be organised using a data extraction table using a descriptive coding tool. -

In Your Area: London Region

In your area: London region Supporting you locally In your area – London region 1 Our mission: We look after doctors so they can look after you. Our values: Expert Challenging We are an indispensable source of credible We are unafraid to challenge effectively on behalf information, guidance and support throughout of all doctors. doctors’ professional lives. Leading Committed We are an influential leader in supporting the We are committed to all doctors and place them at profession and improving the health of our nation. the heart of every decision we make. Reliable We are doctors’ first port of call because we are trusted and dependable. 2 British Medical Association Code of conduct Our behaviours We have taken the BMA’s values – expert, leading, Members are required to familiarise themselves with challenging, committed and reliable – and with your the BMA’s constitution as set out in the memorandum help, turned them into behaviours to provide clarity and articles of association and bye-laws of the on what we expect from each other as we go about our Association. The code of conduct provides guidance work and provide a consistent approach for discussing on expected behaviour and sets out the standards of behaviour. They describe what we expect of each other, conduct that support BMA’s values in the work it does. and what we don’t, as well as what is considered above www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/committees/ and beyond. Our behaviours form part of our culture committee-policies/bma-code-of-conduct) change to become a better BMA. -

EUSTON AREA PLAN Background Report Proposed Submission Draft January 2014

EUSTON AREA PLAN Background Report Proposed submission Draft January 2014 BACKGROUND REPORT Euston Area Plan January 2014 CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Strategic context 6 3. People and population 15 4. Housing 22 5. Economy and employment 29 6. Town centres and retail 36 7. Heritage 40 8. Urban design 53 9. Land ownership 74 10. Transport and movement 75 11. Social and community infrastructure 82 12. Culture, entertainment and leisure 95 13. The environment 97 14. Planning obligations/ Community Infrastructure Levy 112 15. Main policy alternatives assessment 114 16. Conclusions 132 Appendices: Appendix 1 Policy summary Appendix 2 High Speed Two safeguarding map Appendix 3 Impact of tall Buildings on strategic and local views Appendix 4 Euston Station passenger counts Appendix 5 Existing bus routes, stands and stops Appendix 6 Existing road network Appendix 7 Cycling facilities in the Euston area Appendix 8 Community facilities in the study area Appendix 9 Assessment of sites – provision for Travellers 1 2 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Background Report provides the context for the Euston Area Plan, including key issues and existing policies and guidance which are relevant to the plan and its development. It summarises background information from a range of sources, including Census data and evidence base studies that have been prepared to inform the Euston Area Plan. This report is being prepared to provide a background and evidence base summary for the preparation of the Area Plan, and to enable the plan itself to focus on the objectives, policies and proposals for the area. 1.2 Where relevant, this Background Report summarises the planning policy context that is relevant to the production of the Euston Area Plan. -

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 18 April 2011 i) CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 0 Purpose of the Appraisal ............................................................................................................ 2 Designation................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 4 3.0 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST........................................................................................ 5 Context and Evolution................................................................................................................ 5 Spatial Character and Views ...................................................................................................... 6 Building Typology and Form....................................................................................................... 8 Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials ............................................................................ 10 Characteristic Details................................................................................................................ 10 Landscape and Public Realm.................................................................................................. -

Woburn House Conference Centre Directions

Woburn House Conference Centre directions: By Underground Russell Square served by Piccadilly line Kings Cross/St Pancras served by Victoria line, Northern line (City branch), Piccadilly line, Hammersmith and City line, Circle line, Metropolitan line Euston served by Victoria line, Northern line (both branches) Euston Square served by Hammersmith and City line, Circle line, Metropolitan line. By foot from London train terminus Walking distance from Kings Cross/St Pancras, Euston. By bus from London train terminus Bus stops for all main line stations are located in Tavistock Square or Euston Station Square forecourt. By car There is no car parking at Woburn House. The nearest parking is on metered parking in Tavistock Square. There are also parking meters in neighbouring streets. The nearest longstay car park is NCP Russell Court on the corner of Woburn Place and Coram Street WC1. Entrance to Woburn House The main entrance to Woburn House is opposite the gardens at the north end of Tavistock Square. There are two goods entrances in Tavistock Square and Upper Woburn Place. Please report to the reception desk at the main entrance to arrange for either goods entrance to be opened. Wheelchair access is via the main entrance Hotels near Tavistock Square The Euro Hotel 51-53 Cartwright Gardens, London, Greater London, WC1H 9EL Distance: 0.2 miles away average price per room/night: 44.10 GBP -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The George Hotel 58-60 Cartwright Gardens, London, Greater London, WC1H -

CONNAUGHT HALL Bed and Breakfast Accommodation for Visitors

STAY CENTRAL WELCOME TO CONNAUGHT HALL bed and breakfast accommodation for visitors www.staycentral.london.ac.uk /StayCentralUoL ABOUT US USEFUL CONTACTS The University of London is a federal university consisting of a number of self-governing CONNAUGHT HALL colleges and other smaller research institutes of outstanding reputation. It is one of the oldest, [email protected] largest and most diverse universities in the UK. +44 (0) 207 756 8200 It was established by Royal Charter in 1836 and 36 – 45 Tavistock Square is recognised globally as a world leader in higher London education. WC1H 9EX Stay Central offers a great range of Reception open 24/7 accommodation options, from single and double rooms with breakfast to 3 bedroom self-catered apartments, in superb central London locations BOOKINGS just a few minutes walk from London’s most iconic attractions. All rooms are located in the [email protected] University of London’s Halls of Residence, whilst +44 (0) 207 862 8881 our apartments are situated in self-contained residential buildings in the historic Bloomsbury Stay Central area. Whether you are here for business or UoL Housing Services, Student Central leisure, we have a place to suit your needs. Malet Street London Connaught Hall was established by HRH WC1E 7HY Prince Arthur, the Duke of Connaught, the 3rd son of Queen Victoria, in 1919, at Torrington Square. Open Monday to Friday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m. He gave the Hall to University of London as a Tuesday 11 a.m. – 5 p.m. gift in 1928 – the university naming the hall after him as a sign of appreciation. -

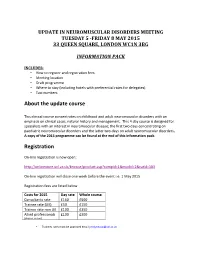

About the Update Course Registration

UPDATE IN NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS MEETING TUESDAY 5 -FRIDAY 8 MAY 2015 33 QUEEN SQUARE, LONDON WC1N 3BG INFORMATION PACK INCLUDES: • How to register and registration fees • Meeting location • Draft programme • Where to stay (including hotels with preferential rates for delegates) • Taxi numbers About the update course This clinical course concentrates on childhood and adult neuromuscular disorders with an emphasis on clinical cases, natural history and management. This 4 day course is designed for specialists with an interest in neuromuscular disease; the first two days concentrating on paediatric neuromuscular disorders and the latter two days on adult neuromuscular disorders. A copy of the 2015 programme can be found at the end of this information pack. Registration On-line registration is now open: http://onlinestore.ucl.ac.uk/browse/product.asp?compid=1&modid=2&catid=183 On-line registration will close one week before the event i.e. 1 May 2015. Registration fees are listed below Costs for 2015 Day rate Whole course Consultants rate £150 £500 Trainee rate (UK) £50 £150 Trainee rate non UK £100 £350 Allied professionals £100 £300 (physios, nurses) • Trainees rates must be approved email [email protected] CPD credits for this event (6 credits per day) has be sought from the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Please note that under the terms and conditions of booking a refund can only made at 80% if the cancellation is made 14 days before the booking – the link for the terms and conditions can be found at: http://onlinestore.ucl.ac.uk/help/?HelpID=1 How to get to 33 Queen Square Location Location map http://dementia.ion.ucl.ac.uk/images/Outpatients%20Map.pdf (map) Lecture theatre The lecture theatre is situated on the lower ground of 33 Queen Square. -

The London Mental Health Fact Book a Cavendish Square Group Publication

CSG - Factbook Cover-JULY 2015-PRINT.qxt_Layout 1 24/07/2015 14:58 Page 1 The London Mental Health Fact Book A Cavendish Square Group publication @CavendishSG #CSGFactBook The Cavendish Square Group is a collaboration between the ten London Trusts responsible for mental health services. The Cavendish Square Group is a collaboration between the ten London Trusts responsible for mental health services. CSG - Factbook Cover-JULY 2015-PRINT.qxt_Layout 1 24/07/2015 14:58 Page 2 2 The London Mental Health Fact Book Contents Foreword About the Cavendish Square Group About the London Mental Health Fact Book Some key statistics about mental health A glossary of useful terms London’s mental health – some key issues Integrated care Young people Mothers and babies Crisis care Out of hospital care Mental health and crime Directory of London Trusts responsible for mental health care Directory of third sector organisations and support groups A Cavendish Square Group publication 3 Foreword The Cavendish Square Group offers a collective voice for the providers of NHS mental health services in London, and for the broader mental health community including clinicians and patients. We want to raise our voice for the cause of good mental health. The Cavendish Square Group has three objectives Close the life expectancy gap for people in London with mental health problems and to ensure they receive the treatment they need Make London the most mental health-friendly economy in the world Ensure London is a centre of excellence for supporting the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. The Government has promised to increase funding for mental health care and ensure there are teams in every part of the country providing treatment for those who need it. -

Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission Year Ending 30 September 2013

ANNUAL REPORT Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission Year ending 30 September 2013 A Non-Departmental Public Body of 60 Sixtieth Annual Report of the Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission for the year ending 30 September 2013 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs pursuant to section 2(6) of Marshall Aid Commemoration Act 1953 A Non-Departmental Public Body of March 2014 Sixtieth Annual Report: Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission © Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission (2014) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission’s copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications Print ISBN 9781474100267 Web ISBN 9781474100274 Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID P002625532 03/14 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum 4 Sixtieth Annual Report: Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission Contents Introduction 6 Welcome from the MACC Chair Dr John Hughes 6 MACC Membership and Meetings -

Bloomsbury Gardens

Bloomsbury Gardens Most of our PaLS buildings are located in Bloomsbury, a famous area of garden squares and gardens. Why don’t you make your lunch hour a journey of discovery! Pick a garden a day and start strolling! Walk in airy spaces breathing history that spans from 1660 to recent days. Most of us probably know that Virginia Woolf, amongst several members of the Bloomsbury Group, lived in Gordon Square in the first half of the 20th century, but did you know that in Jane Austen’s Emma , Mr and Mrs John Knightley live in Brunswick Square? Where did Tracy Emin leave her Can you find Mitten? the Green Man? Are you in search of the sarsen stone? Bloomsbury Gardens Most of our PaLS buildings are located in Bloomsbury, a famous area of garden squares and gardens. Why don’t you make your lunch hour a journey of discovery! Pick a garden a day and start strolling! Walk in airy spaces breathing history that spans from 1660 to recent days. Bloomsbury Gardens Most of our PaLS buildings are located in Bloomsbury, a famous area of garden squares and gardens. Why don’t you make your lunch hour a journey of discovery! Pick a garden a day and start strolling! Walk in airy spaces breathing history that spans from 1660 to recent days. Follow the links to find out the history of the gardens Argyle Square https://bloomsburysquares.wordpress.com/argyle-square/ Bedford Square https://bloomsburysquares.wordpress.com/bedford-square/ Bloomsbury Square https://bloomsburysquares.wordpress.com/bloomsbury-square/ Brunswick Square https://bloomsburysquares.wordpress.com/brunswick-square/ -

BMA House Location Map

BMA House Location Map BMA HOUSE King’s Cross E LE ROAD E BMA House directions V ONVIL S E NT I RS St Pancras E R P N H G O T O R Directions from Euston Station L A N T Y E British ’ P H S S T Walk into the station forecourt with the platforms behind you and head towards A Library R IN M E N the exits to the left of the station. You should walk to the main road on the left E P T R K S O T A I N which is Eversholt Street. Turn right onto this road and walk down to the traffic E D G A Euston ’ D S lights at the junction with Euston Road. Cross straight over the road which J R U C AD O D O R turns into Upper Woburn Place. There will be a Prezzo restaurant on the right R D A N S O D O U ST T S hand corner. Walk down this road and at the Hilton Hotel cross the road at the R S P U E E P E R E T O zebra crossing. Keep walking until you reach the Natwest bank. The BMA House R A D W O G entrance is the next main door and is signed BMA Reception. If you reach the D B R A O U H A R R Y Starbucks coffee shop you have gone too far. N U O N ’ T N S S U P T I E N L E A E R N C T A Euston C L S S P R E Directions from Kings Cross Station K T E C O Square Tavistock R P O T E A R IS Coram’s D Square E O Walk out of the main exit of the station – you will be on Euston Road. -

Bloomsbury CA Sub Area 1Townscape Appraisal * Unauthorised Reproduction Infringes Crown Copyright and May Lead to Prosecution Or Civil Proceedings

Royal George 6 to Wellesley House 1 PH (PH) 8 to 14 St James's Gardens Bank Bloomsbury Sub Area 1 D Fn 122 124 Listed Building 135 TCBs WELLESLEYPLACE 24.0m 21.4m 4 1 to 11 139 137 Hotel Positive Buildings 1 3 1 GRAFTON PLACE TCBs 22.9m Sub Area 1 71 Air 141 Exmouth Shaft Arms 70 (PH) Underground Railway 156 to 160 EUSTON SQUARE Fire Hotel 69 Station Somerton House 35 COBOURG STREET 22.4m 40 29 34 Cycle Hire Station Statue 28 EUSTON ROAD 30 27 44 42 48 46 Ward Bdy 16 Shelter STARCROSS STREET 60 Playground CR FLAXMAN TERRACE 93 to 103 to 93 50 43 to 66 to 43 14 1 62 EXMOUTH MEWS 52 23.7m 54 92 DW DUKE'S ROAD 13 56 94 40 68 TCBs 3 58 11 18 17 Surgery 84 to 67 100 Posts 20 59 54 to 56 UPPER MansionsGrafton War Memorial St Pancras Church 1 to 10 58 2 ME 161 110 115 10 23.5m 4 DW LTON STREET Flaxman Shelter Bank WO 6 DRUMMOND STREET PH 64 Lodge 69 Shelter 165 BURN PLACE 22 163 16 10 125 10 67 to 71 to 67 22 45 167 PO 23.7m STEPHENSON WAY 14 Hotel Euston Square 133 75 Central House 72 135 Gardens The London 16 77 79 77 Hotel 169 Wa Contemporary Tavistock House 18 rd Bdy 9 RE Dance School (University College) Government Offices 82 EUSTON STREETGNART BUILDINGS CR East Wolfson House 84 4 1 81 to 103 to 81 24.5m 30 9 Shelter New EUSTON SQ Ambassadors Euston Plaza Hotel 4 92 Leslie FosterHouse UA Hotel Woburn Walk 180 94 RE Bentham TCBs 178 100 Shelter House 174 to 111 to 105 County Hotel 176 Thorne House 30 Scandic Crown 12 Fn Hotel TCB 117 14 to 16 172 11 to 9 UPPER WOBURN PLACE CR 1 18 to 20 Friends House 170 British Medical Tav 2 22 194 to 198