University of Kwazulu-Natal Unlocking Local Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Bantu Biko: an Agent of Change in South Africa’S Socio-Politico-Religious Landscape

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research Stephen Bantu Biko: An agent of change in South Africa’s socio-politico-religious landscape Author: This article examines and analyses Biko’s contribution to the liberation struggle in 1 Ramathate T.H. Dolamo South Africa from the perspective of politics and religion. Through his leading participation Affiliation: in Black Consciousness Movement and Black Theology Project, Biko has not only influenced 1Department of Philosophy, the direction of the liberation agenda, but he has also left a legacy that if the liberated and Practical and Systematic democratic South Africa were to follow, this country would be a much better place for all to Theology, University of live in. In fact, the continent as a whole through its endeavours in the African Union South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa underpinned by the African Renaissance philosophy would go a long way in forging unity among the continent’s nation states. Biko’s legacy covers among other things identity, Corresponding author: human dignity, education, research, health and job creation. This article will have far Ramathate Dolamo, reaching implications for the relations between the democratic state and the church in [email protected] South Africa, more so that there has been such a lack of the church’s prophecy for the past Dates: 25 years. Received: 12 Feb. 2019 Accepted: 22 May 2019 Keywords: Liberation; Black consciousness; Black theology; Self-reliance; Identity; Culture; Published: 29 July 2019 Religion; Human dignity. How to cite this article: Dolamo, R.T.H., 2019, ‘Stephen Bantu Biko: An Orientation agent of change in South Biko was born in Ginsberg near King William’s Town on 18 December 1946. -

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps DRAFT May 2009 South African National Biodiversity Institute Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Contents List of tables .............................................................................................................................. vii List of figures............................................................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2 Criteria for identifying threatened ecosystems............................................................... 10 3 Summary of listed ecosystems ........................................................................................ 12 4 Descriptions and individual maps of threatened ecosystems ...................................... 14 4.1 Explanation of descriptions ........................................................................................................ 14 4.2 Listed threatened ecosystems ................................................................................................... 16 4.2.1 Critically Endangered (CR) ................................................................................................................ 16 1. Atlantis Sand Fynbos (FFd 4) .......................................................................................................................... 16 2. Blesbokspruit Highveld Grassland -

Vulamehlo Plan

TABLE OF CONTENTS DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. Executive Summary 5 1.0 Purpose and objectives 7 2.0 Legislative Framework 8 3.0 Methodology 11 3.1 Data Collection Process 11 3.2 Background and Local Context 12 4.0 Vulamehlo Demographic Information 13 5.0 Basic Infrastructure Services 16 5.1 Source of Energy 16 5.2 Roads 16 5.3 Water Supply 17 5.4 Sanitation 18 6.0 Spatial Development Framework 19 5.1 BNG Strategy 22 5.2 Spatial Development Plan 22 5.3 Integration with Other Sectors 25 7.0 Housing Demand 26 7.1 Current Housing Structures 26 7.2 Current Settlement Pattern 27 7.3 Housing Backlog 28 7.4 Current Housing Subsidy Band 29 7.5 Current Housing Projects 30 7.6 Planned Housing Projects 32 7.7 Cash-flow Projections 33 8.0 Identification of focus areas 35 8.1 Special Subsidies 35 8.2 Land Identification 35 8.3 Form of Tenure 36 8.4 Land Claims 37 9.0 Location of Current Housing Projects 37 10.0 The Process of Implementing Housing Projects 37 11.0 Process Indicators: Linkages Between Issues & Strategy 39 12.0 Planning & Preparing Projects For Implementation 41 13.0 Monitoring of Housing Projects 42 14.0 Performance Indicators 43 15.0 Proposed Projects Management Structure 45 16.0 Proposed Projects Operational Structure 46 17.0 Conclusions & Recommendations 48 18.0 Reference Section 55 19.0 Addendum Section 2 ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CEC Committee for Environmental Co-ordination CMIP Consolidated Municipal Infrastructure Program DFA Development Facilitation Act DM District Municipality DoH Department of Housing ECA Environmental Conservation -

Ugu District Municipality

UGU DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT January 2018 TITLE AND APPROVAL PAGE Project Name: Ugu District Municipality Environmental Management Framework Report Title: Strategic Environmental Management Plan Authority Reference: N/A Report Status Draft Client: Prepared By: Nemai Consulting +27 11 781 1730 147 Bram Fischer Drive, +27 11 781 1731 FERNDALE, 2194 [email protected] PO Box 1673, SUNNINGHILL, www.nemai.co.za 2157 Report Reference: 10623–20180116-SEMP R-PRO-REP|20150514 Name Date Author: D. Henning 16/01/2018 Reviewed By: N. Naidoo 16/01/2018 This Document is Confidential Intellectual Property of Nemai Consulting C.C. © copyright and all other rights reserved by Nemai Consulting C.C. This document may only be used for its intended purpose Ugu DM EMF SEMP (Draft) AMENDMENTS PAGE Amendment Date: Nature of Amendment Number: 22/09/2017 First Version for Review by the Project Steering Committee 0 16/01/2018 Second Version for Review by the Public 1 Ugu DM EMF SEMP (Draft) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Ugu District Municipality, in partnership with the Department of Environmental Affairs and KwaZulu-Natal Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs, embarked on a process to develop an Environmental Management Framework for the district. Nemai Consulting was appointed to only compile the Strategic Environmental Management Plan, based on the outcomes of the Status Quo and Desired State phases of the overall Environmental Management Framework process. An Environmental Management Framework is a study of the biophysical and socio-cultural systems of a geographically defined area to reveal where specific activities may best be practiced and to offer performance standards for maintaining appropriate use of such land. -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

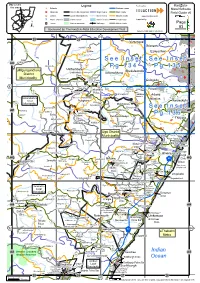

Provincial Road Network Provincial Road Network All Other Roads P, Concrete L, Blacktop G, Blacktop On-Line Roads .! Major !C Clinics

D D 2206 248 24 Kwakhwela P OL0 8 P 52 4 D 31 69 6 27 P4 9 4 Ntimbankulu 9 !. 2 3 D D 1 1 1 1 0 8 0 Ndlandlama P 1 315 D D 31 Isisusa S 10 24 Einsiedeln C D 7 D 545 452 1 Khulabebuka S R624 Empumelelweni P 7 0 D 22 Nwabi S L0 9 Mgada Cp O 8 Esiphukwini Jp 4 2 107 8 P Phangisa P 6 P11 Bridgeman P Sikhwama H Mhawu H Emadundube P L Engonyameni P 1 Hope 0 3 16 0 435 Valley P 73 Nomavimbela H 1 O D L KZN211 0 2 L1 2 Umlazi K 6 67 0 3 D 58 L1 8 Provincial 419 D 67 9 P72 454 4 8 5 Clinic 6 453 L 1 Mpulule P 5 09_A 7 L022 Sibukeyana P 5 0 O 6 P O 1 2 D 66 L 1 1 O 0 2 - 2 2 1 L 2 0 0 0 2 9 L 2 _ O 2 B Rosettenstein P KZN212 433 8 L 2 Inkanyezi P 6 OL02 456 4 210 1 214 OL02 M Duze Cp b D o ni 9 kodwe 16 83 Arden 022 5 432 OL O 1 7 2 Farm L 1 2 0 0 D 2 Ndonyela Js 2 L Amandus 3 OL022 2 26 6 6 2 O 8 0 1 7 Hill P L 2 2 1 L O Ekudeyeni SP Kwagwegwe P L 1 M 7 2 2 451 KZN213 Bambinkunzi P Putellos P 7 g 2 OL Intinyane P 2 022 4 w 2 0 2 Lugobe S O 9 L L Mboko SP a 0 3 578 O 2 1 Folweni L1 h Umbumbulu 22 1 Empusheni P Phindela Hp 7 u 0 L 5 Provincial Clinic 2 m !. -

Learning Zulu: a Secret History of Language in South Africa

Introduction Ngicela uxolo I stand before the class, telling the students who I am, where I come from, and what brings me to the school. I notice as Mr. Nzuza, who is standing at the back of the classroom beside my desk, discreetly opens the book in which I have been taking notes. Although I am not exactly another pupil, he is the teacher and he has every right to examine my notes. He sees that I see him. I continue to speak. Maybe he wants me to have seen him—to be aware that he is watching, but also to know that he is curious to read what I have written. I cannot know whether this is what he intended. Yet my guess at it—which is already shaping the mem- ory—leaves me with a twofold awareness: he is reading, and he is watching. It is within the influence of this awareness that I embark on this book. I have to trust the reader. I have to trust that the one whom I picture as watching me as I write would like to think that he, or she, is reading something I wrote while he, or she, was not watching. If, for the reader whom I picture, to want this is to want the impossible, to imagine writing for such a reader, that is impossibility itself. Yet there is no writing without that step. Not for me, not with this book. Our text is Ngicela uxolo, a play by Nkosinathi I. Ngwane,1 an author I have never heard of. -

Profile of Poverty in the Durban Region

J .. ~ PROFILE OF POVERTY IN THE DURBAN REGION PROJECT FOR STATISTICS ON LIVING STANDARDS AND DEVELOPMENT PREPARED BY J Cobbledick and M Sharratt Economic Research Unit University of Natal Durban OCTOBER 1993 ~, ~' - ( /) .. During 1992 the World Bank approached the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) at the University of Cape Town to coordinate, a study in South Africa called the Project on Statistics for Living $tandards and Development. This study was carried out during 1993, and consisteci of two phases. The first of these was a situation analysis, consisting of a number of regional poverty profiles and cross-cutting studies on a na~ional level. The second phase was a country wide household surVey conducted in the latter half of 1993. The Project has been built on the Second Carnegie Inquiry into Poverty, which assessed the situation up to the mid 1980's. Whilst preparation of these papers for the situation analysis, using common guidelines, involved much discussion and criticism amongst all those involved in the Project, the final paper remains the responsibility of its authors. .' -<, '" -) 1 In the series of working papers on reilional poverty and cross- '"" . cutting themes there are 12 papers: Regional Poverty Profiles: Ciskei Durban Eastern and Northern Transvaal NatallKwazulu OFS and Qwa-Qwa Port Elizabeth - Uitenhage PWV' Transkei Western Cape Cross-Cutting Studies: Energy Nutrition Urbanisation & Housing Water Supply TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION No. PAGE No. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 CONTEXTUALISING THE DURBAN -

9/10 November 2013 Voting Station List Kwazulu-Natal

9/10 November 2013 voting station list KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting Voting station name Latitude Longitude Address district ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400179 NOMFIHLELA PRIMARY -29.66898 30.62643 9 VIA UMSUNDUZI CLINIC, KWA XIMBA, ETHEKWINI Metro] SCHOOL ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400180 OTHWEBA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.69508 30.59244 , OTHEBA, KWAXIMBA Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400191 CATO RIDGE LIBRARY -29.73666 30.57885 OLD MAIN ROAD, CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI Metro] ACTIVITIES ROOM ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400528 NGIDI PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.653894 30.660039 BHOBHONONO, KWA XIMBA, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400539 MVINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.63687 30.671642 MUTHI ROAD, CATO RIDGE, KWAXIMBA Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400595 XIMBA COMMUNITY HALL -29.66559 30.636613 KWAXIMBA MAIN ROAD, NO. 9 AREA, XIMBA TRIBAL Metro] AUTHORITY,CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400607 MABHILA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.683425 30.63102 NAGLE ISAM RD, CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400618 NTUKUSO PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.67385 30.58848 NUBE ROAD, KWAXIMBA, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400696 INGCINDEZI PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.705158 30.577373 ALICE GOSEWELL ROUD, CATO RIDGE, ETHEKWINI Metro] ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400708 INSIMANGWE PRIMARY -29.68598 30.61588 MAQATHA ROAD, CATO RIDGE, KWAXIMBA TC Metro] SCHOOL ETH - eThekwini [Durban 59500001 43400719 INDUNAKAZI PRIMARY -29.67793 30.70337 D1004 PHUMEKHAYA ROAD, -

•A •Ap •Ap •Ar •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ar •Ap •Ap •Ap •Ap

Map covers Legend Produced by: KwaZulu- this area Schools National roads Natal Schools ! Hospitals District Municipalities Major rivers Main roads Field Guide v5 Clinics Local Municipalities Minor rivers District roads www.eduAction.co.za !W Police stations Urban areas Dams / Lakes Local roads Supported by: Towns Nature reserves Railways Minor roads Page 83 Sponsored by: The KwaZulu-Natal Education Development Trust KwaZulu-Natal Dept of Education 1 75 25 26 27 28 ! Kwakhwela P Umlazi 1 District Office O Isisusa S Hope See Inset See Inset See Inset See Inset AO Valley P Bridgeman P AO O Mpulule P O 1 Pg 134 Pg 135 1 uMgungundlovu # Inkanyezi P District # Duze P !W Municipality Putellos P Sibusisiwe Comp Phuph- % Kwagwegwe P Tech H uma Jp 1 1 Khayelihle H Hamilton !W 82 Tobi P 84 Makhanya S Nathaniel Sawpits P O & Sabelo S 1 Bangubukhosi P Emangadini P Charles Nungwane ( Sabelo H 1 Mkhambathini Mbovu P Ngongomisa P Dam Local O Mthambo H Zamakahle H 1 Municipality O Sunduzwayo P !W Powerscourt P Enkanyisweni P See Inset See Inset Odidini P Qiniselani Sp Mdumezulu P AP Ismont S AP Gcewu S Kwaphikaziwa S O Kwajabula H Ondini P $ Pg 136 # O Sikhukhukhu P O Inyonemhlophe S !W Mgoqozi P ) 1 Itshehlophe P Ngoloshini P Saphumula Ss 1 Kwaqumbu P Ugu District Warner Beach Sp Municipality Nungwana -

Biodiversity Assessment June 2013

UGU EMF: Biodiversity Assessment June 2013 Development of an Environmental Management Framework for the Ugu District: Biodiversity Assessment Date: June 2013 Lead Author: Douglas Macfarlane Report No: EP71-02 I UGU EMF: Biodiversity Assessment June 2013 Prepared for: Mott MacDonald South Africa (Pty) Ltd By Please direct any queries to: Douglas Macfarlane Cell: 0843684527 26 Mallory Road, Hilton, South Africa, 3245 Email: [email protected] II UGU EMF: Biodiversity Assessment June 2013 SUGGESTED CITATION Macfarlane, D.M. and Richardson, J. 2013. Development of an Environmental Management Framework for the Ugu District: Biodiversity Assessment. Unpublished report No EP71-02, June 2013. Prepared for Mott MacDonald South Africa (Pty) Ltd by Eco-Pulse Environmental Consulting Services. DISCLAIMER The project deliverables, including the reported results, comments, recommendations and conclusions, are based on the project teams’ knowledge as well information available at the time of compilation and are not guaranteed to be free from error or omission. The study is based on assessment techniques and investigations that are limited by time and budgetary constraints applicable to the type and level of project undertaken. Eco-Pulse Environmental Consulting Services exercises all reasonable skill, care and diligence in the provision of services. However, the authors and contributors also accept no responsibility or consequential liability for the use of the supplied project deliverables (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained therein. FURTHER INFORMATION Much of the information presented in this report was prepared as part of the Biodiversity Sector Plan (BSP) for the Ugu District (Macfarlane et.al., 2013a). Additional information in the form of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) shapefiles used to prepare the Critical Biodiversity Areas Maps referred to in this status quo report, together with the original BSP report and associated guidelines can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. -

Annual Report for Vulamehlo Municipality

VULAMEHLO MUNIPALITY DRAFT ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT FOR VULAMEHLO MUNICIPALITY VISION By 2025 the Vulamehlo Local Municipality will be self-sustainable and economically viable through agricultural and tourism initiatives and the establishment of a vibrant town. MISSION STATEMENT The purpose of the Vulamehlo Local Municipality is to facilitate and co-ordinate the provision of sustainable infrastructure and services, thereby creating an enabling environment that allows the active involvement of the broader community, in order to improve the quality of life of all residents within Vulamehlo Local Municipality. VALUES The Vulamehlo Municipality seeks to uphold and promote the values of responsiveness, transparency, accountability, innovation, consultation and service excellence. TABLE OF CONTENT PAGE Foreword By His Worship the Mayor Message from the Municipal Manager Chapter 1 : Overview of Vulamehlo Municipality Chapter 2 : Performance Highlights Chapter 3 : Organisational and Human Resource Arrangements • Political Structure • Management Team • Functions Assigned to Departments • Human Resource Statistics Chapter 4 : Service Delivery Report • Department of Corporate Services • Department of Technical Services • Department of Financial Services • Department of Development Planning & LED Chapter 5 : Report of the Auditor- General Chapter 6 : Report of the Audit Committee Chapter 7 : Annual Financial Statements FOREWORD BY HIS WORSHIP THE MAYOR Cllr WT Dube Mayor I would like to pass a vote of gratitude to all councillors, municipal officials, traditional leadership, church leaders, sector departments and the community at large for all the support they have given me during the period under review. Despite all the challenges and obstacles faced by our municipality, both at community level and at an organisational level, we have managed to deliver on road infrastructure, community facilities, have co-ordinated the supply of potable water to a large number of our communities.