Flight, a Novel.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gone Girl : a Novel / Gillian Flynn

ALSO BY GILLIAN FLYNN Dark Places Sharp Objects This author is available for select readings and lectures. To inquire about a possible appearance, please contact the Random House Speakers Bureau at [email protected] or (212) 572-2013. http://www.rhspeakers.com/ This book is a work of ction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used ctitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2012 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Dark Places” copyright © 2009 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Sharp Objects” copyright © 2006 by Gillian Flynn All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flynn, Gillian, 1971– Gone girl : a novel / Gillian Flynn. p. cm. 1. Husbands—Fiction. 2. Married people—Fiction. 3. Wives—Crimes against—Fiction. I. Title. PS3606.L935G66 2012 813’.6—dc23 2011041525 eISBN: 978-0-307-58838-8 JACKET DESIGN BY DARREN HAGGAR JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY BERND OTT v3.1_r5 To Brett: light of my life, senior and Flynn: light of my life, junior Love is the world’s innite mutability; lies, hatred, murder even, are all knit up in it; it is the inevitable blossoming of its opposites, a magnicent rose smelling faintly of blood. -

Konkurs Poezji I Piosenki Irlandzkiej – Marzec 2021

Konkurs Poezji i Piosenki Irlandzkiej – marzec 2021 PATRONATY HONOROWE: Ambasada Irlandii w Warszawie Konsulat Irlandii w Poznaniu PATRONAT MEDIALNY: ORGANIZATOR I SPONSOR: Szkoła Języków Obcych Program sp. z o.o. www.angielskiprogram.edu.pl https://www.facebook.com/angielskiprogram.poznan SPONSORZY: 1 Szanowni Uczniowie! Zapraszam Was do wzięcia udziału w XVII edycji Konkursu Poezji Irlandzkiej, którego finał odbędzie się w Poznaniu 19 marca 2021 roku ( piątek) w Sali Kameralnej Szkoły Muzycznej II stopnia im. M. Karłowicza przy ul. Solnej w Poznaniu. Szesnaście dotychczasowych spotkań z poezją irlandzką, zarówno tą mówioną, jak i śpiewaną, to szesnaście wspaniałych przeżyć, które pozostaną nam w pamięci. Historia tych lat pokazała, że młodzież polska rozumie i ceni poezję irlandzką i potrafi ją zinterpretować nie gorzej niż rodowici mieszkańcy Zielonej Wyspy. Cieszy mnie niezmiernie, że inicjatywa szkoły PROGRAM (dawniej Program-Bell) przyjęła się wśród młodzieży w naszym regionie i dzięki niej anglojęzyczna poezja Irlandii stała się lekturą i przedmiotem interpretacji słownych i muzycznych. Motto tegorocznego Konkursu to słowa Samuela Beckett’a ”If you do not love me, I shall not be loved. If I do not love you, I shall not love.” W tym roku wybór utworów jest podyktowany szczególnym czasem, w którym przyszło nam żyć i jako przeciwwaga tych trudnych czasów poświęcony jest miłości, przetrwaniu, czy przemijaniu, wierszy smutnych wielokrotnie, nacechowanych jednak zawsze odrobiną optymizm. Rok ten jest też wyjątkowy, bo więcej kobiet staje się widocznych w życiu społecznym i kobiety stają się coraz bardziej znaczącym głosem, który wybrzmiewa publicznie. W tomiku zaprezentujemy trzy nazwiska poetek, takie jak: Eavan Boland, Katharine Tynan czy Eileen Carney Hulme, w tym wiersz Eavan Boland o znamiennym tytule „Quarantine”. -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

How to Be Dead Dave Turner

Contents Title Page Dedication Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Paper Cuts - Chapter One Chapter One Keep Reading! About The Author Big List of Awesome Copyright How To Be Dead Dave Turner Aim For The Head Books For Zoë For everything CHAPTER ONE Death watched the city sleep. He gazed down at humanity's glow from the top floor of the office block. A sleek and thrusting tower made from glass, chrome and undisguised wealth. He was waiting. He was good at that. He checked his pocket watch. A gift from three old friends. Crafted for him by Patek Philippe & Company in 1933 with a movement as complicated and precise as the dance of the stars that he had counted for millennia. Sometimes, as he gazed up at the night sky, he wondered if the universe was some kind of in-joke that had got out of hand and was working up to an awkward punchline. He had explained his theory when he and Einstein had briefly met. Nice guy. Good hair. That was back in 1955 and Death had not seen anything since to change his mind. He did not know how long he had existed. He thought he remembered the dinosaurs. An asteroid killed them, hadn't it? Was he there? Or had he merely read it in a book? All he was sure of? It's the sort of thing that happens when you live in a world without Bruce Willis. -

Personality and Dvds

personality FOLIOS and DVDs 6 PERSONALITY FOLIOS & DVDS Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Songbooks of the legendary recordings that defined and shaped rock and roll! Alfred’s Classic Album Editions Alfred’s Eagles Desperado Led Zeppelin I Titles: Bitter Creek • Certain Kind of Fool • Chug All Night • Desperado • Desperado Part II Titles: Good Times Bad Times • Babe I’m Gonna Leave You • You Shook Me • Dazed and • Doolin-Dalton • Doolin-Dalton Part II • Earlybird • Most of Us Are Sad • Nightingale • Out of Confused • Your Time Is Gonna Come • Black Mountain Side • Communication Breakdown Control • Outlaw Man • Peaceful Easy Feeling • Saturday Night • Take It Easy • Take the Devil • I Can’t Quit You Baby • How Many More Times. • Tequila Sunrise • Train Leaves Here This Mornin’ • Tryin’ Twenty One • Witchy Woman. Authentic Guitar TAB..............$22.95 00-GF0417A____ Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............$16.95 00-25945____ UPC: 038081305882 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4697-5 UPC: 038081281810 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4258-8 Authentic Bass TAB.................$16.95 00-28266____ UPC: 038081308333 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-4818-4 Hotel California Titles: Hotel California • New Kid in Town • Life in the Fast Lane • Wasted Time • Wasted Time Led Zeppelin II (Reprise) • Victim of Love • Pretty Maids All in a Row • Try and Love Again • Last Resort. Titles: Whole Lotta Love • What Is and What Should Never Be • The Lemon Song • Thank Authentic Guitar TAB..............$19.95 00-24550____ You • Heartbreaker • Living Loving Maid (She’s Just a Woman) • Ramble On • Moby Dick UPC: 038081270067 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-3919-9 • Bring It on Home. -

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge and Other Stories

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge and Other Stories by Ambrose Bierce Web-Books.Com An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge and Other Stories The Affair at Coulter..............................................................................................4 An Affair of Outposts...........................................................................................11 A Baby Tramp.....................................................................................................19 Beyond the Wall..................................................................................................23 The Boarded Window .........................................................................................29 Chickamauga......................................................................................................32 The Coup De Grâce............................................................................................37 The Crime at Pickett ...........................................................................................41 The Damned Thing .............................................................................................48 The Death of Halpin Frayser...............................................................................56 A Diagnosis of Death ..........................................................................................68 Four Days in Dixie...............................................................................................71 George Thurston Three Incidents in the Life of a Man........................................78 -

Cdg-Mp3 Karaoke: S – Z - 13.631 Datotek

Cdg-Mp3 karaoke: S – Z - 13.631 datotek S Club - Alive [SF Karaoke] S Club - Love Ain't Gonna Wait For You [SF Karaoke] S Club - Say Goodbye [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Alive [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Best Friend [Homestar Karaoke] S Club 7 - Best Friend [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Bring It All Back [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Bring It All Back [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [AS Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [MF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [PI Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [SB Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Don't Stop Moving [Z Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [Homestar Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [PI Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Have You Ever [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - I'll Be There [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Love Ain't Gonna Wait For You [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Natural [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Natural [MF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Natural [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [MM Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had a Dream Come True [NS Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Never Had A Dream Come True [STW Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [MF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [PI Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [SC Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [SF Karaoke] S Club 7 - Reach [Z Karaoke] S Club 7 - S Club Party [EK Karaoke] S Club 7 - S Club Party [SC Karaoke] -

Defaming the Dead Don Herzog New Haven and London

Defaming the Dead Don Herzog New Haven and London for the University of Michigan Law School The just and proper jealousy with which the law protects the reputation of a living man forms a curious contrast to its impotence when the good name of a dead man is attacked. When a man dies, the law will secure that any reasonable provision which he has made for the disposal of his property is duly carried into effect and that his money shall pass to those whom he has selected as his heirs. He leaves behind him a reputation as well as an estate, but the law, so zealous in its regard for the material things, has no protection to give to that which the dead man regarded as a more precious possession than money or lands. The dead cannot raise a libel action, and it is possible to bring grave charges against their memory without being called upon to justify these charges in a court of law or to risk penalties for slander and defamation. The possibilities of injustice are obvious…. –“Libelling the Dead,” Glasgow Herald (27 July 1926) Contents Preface . i One / Embezzled, Diddled, and Popped . 1 Two / Tort’s Landscape . 22 Three / Speak No Evil . 55 Four / Legal Dilemmas . 83 Five / Corpse Desecration . 128 Six / “This Will Always Be There” . 176 -i- Preface Rhode Island has a curious statute. It says that if you’re defamed in an obituary within three months of your death, your estate can sue. Why curious? Because as far as I know, it’s the only such law in the United States. -

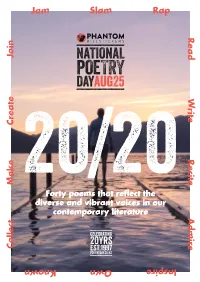

Jam Inspire Create Join Make Collect Slam Own Rap Known Read W Rite

Jam Slam Rap Read Join Write Create Recite Make 20/20 Forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant voices in our contemporary literature Admire Collect Inspire Known Own 20 ACCLAIMED KIWI POETS - 1 OF THEIR OWN POEMS + 1 WORK OF ANOTHER POET To mark the 20th anniversary of Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, we asked 20 acclaimed Kiwi poets to choose one of their own poems – a work that spoke to New Zealand now. They were also asked to select a poem by another poet they saw as essential reading in 2017. The result is the 20/20 Collection, a selection of forty poems that reflect the diverse and vibrant range of voices in New Zealand’s contemporary literature. Published in 2017 by The New Zealand Book Awards Trust www.nzbookawards.nz Copyright in the poems remains with the poets and publishers as detailed, and they may not be reproduced without their prior permission. Concept design: Unsworth Shepherd Typesetting: Sarah Elworthy Project co-ordinator: Harley Hern Cover image: Tyler Lastovich on Unsplash (Flooded Jetty) National Poetry Day has been running continuously since 1997 and is celebrated on the last Friday in August. It is administered by the New Zealand Book Awards Trust, and for the past two years has benefited from the wonderful support of street poster company Phantom Billstickers. PAULA GREEN PAGE 20 APIRANA TAYLOR PAGE 17 JENNY BORNHOLDT PAGE 16 Paula Green is a poet, reviewer, anthologist, VINCENT O’SULLIVAN PAGE 22 Apirana Taylor is from the Ngati Porou, Te Whanau a Apanui, and Ngati Ruanui tribes, and also Pakeha Jenny Bornholdt was born in Lower Hutt in 1960 children’s author, book-award judge and blogger. -

Feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77

01. 50 Cent - Intro (0:06) 75. Ace Of Base - Life Is A Flower (3:44) 02. 50 Cent - What Up Gangsta? (2:59) 76. Ace Of Base - C'est La Vie (3:27) 03. 50 Cent - Patiently Waiting (feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77. Ace Of Base - Lucky Love (Frankie Knuckles Mix) 04. 50 Cent - Many Men (Wish Death) (4:16) (3:42) 05. 50 Cent - In Da Club (3:13) 78. Ace Of Base - Beautiful Life (Junior Vasquez Mix) 06. 50 Cent - High All the Time (4:29) (8:24) 07. 50 Cent - Heat (4:14) 79. Acoustic Guitars - 5 Eiffel (5:12) 08. 50 Cent - If I Can't (3:16) 80. Acoustic Guitars - Stafet (4:22) 09. 50 Cent - Blood Hound (feat. Young Buc) (4:00) 81. Acoustic Guitars - Palosanto (5:16) 10. 50 Cent - Back Down (4:03) 82. Acoustic Guitars - Straits Of Gibraltar (5:11) 11. 50 Cent - P.I.M.P. (4:09) 83. Acoustic Guitars - Guinga (3:21) 12. 50 Cent - Like My Style (feat. Tony Yayo (3:13) 84. Acoustic Guitars - Arabesque (4:42) 13. 50 Cent - Poor Lil' Rich (3:19) 85. Acoustic Guitars - Radiator (2:37) 14. 50 Cent - 21 Questions (feat. Nate Dogg) (3:44) 86. Acoustic Guitars - Through The Mist (5:02) 15. 50 Cent - Don't Push Me (feat. Eminem) (4:08) 87. Acoustic Guitars - Lines Of Cause (5:57) 16. 50 Cent - Gotta Get (4:00) 88. Acoustic Guitars - Time Flourish (6:02) 17. 50 Cent - Wanksta (Bonus) (3:39) 89. Aerosmith - Walk on Water (4:55) 18. -

234 MOTION for Permanent Injunction.. Document Filed by Capitol

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 237 Att. 12 EXHIBIT 12 Dockets.Justia.com CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP WORLDWIDE PLAZA ROBERT O. JOFFE JAMES C. VARDELL, ID WILLIAM J. WHELAN, ffl DAVIDS. FINKELSTEIN ALLEN FIN KELSON ROBERT H. BARON 825 EIGHTH AVENUE SCOTT A. BARSHAY DAVID GREENWALD RONALD S. ROLFE KEVIN J. GREHAN PHILIP J. BOECKMAN RACHEL G. SKAIST1S PAULC. SAUNOERS STEPHEN S. MADSEN NEW YORK, NY IOOI9-7475 ROGER G. BROOKS PAUL H. ZUMBRO DOUGLAS D. BROADWATER C. ALLEN PARKER WILLIAM V. FOGG JOEL F. HEROLD ALAN C. STEPHENSON MARC S. ROSENBERG TELEPHONE: (212)474-1000 FAIZA J. SAEED ERIC W. HILFERS MAX R. SHULMAN SUSAN WEBSTER FACSIMILE: (212)474-3700 RICHARD J. STARK GEORGE F. SCHOEN STUART W. GOLD TIMOTHY G. MASSAD THOMAS E. DUNN ERIK R. TAVZEL JOHN E. BEERBOWER DAVID MERCADO JULIE SPELLMAN SWEET CRAIG F. ARCELLA TEENA-ANN V, SANKOORIKAL EVAN R. CHESLER ROWAN D. WILSON CITYPOINT RONALD CAM I MICHAEL L. SCHLER PETER T. BARBUR ONE ROPEMAKER STREET MARK I. GREENE ANDREW R. THOMPSON RICHARD LEVIN SANDRA C. GOLDSTEIN LONDON EC2Y 9HR SARKIS JEBEJtAN DAMIEN R. ZOUBEK KRIS F. HEINZELMAN PAUL MICHALSKI JAMES C, WOOLERY LAUREN ANGELILLI TELEPHONE: 44-20-7453-1000 TATIANA LAPUSHCHIK B. ROBBINS Kl ESS LING THOMAS G. RAFFERTY FACSIMILE: 44-20-7860-1 IBO DAVID R. MARRIOTT ROGER D. TURNER MICHAELS. GOLDMAN MICHAEL A. PASKIN ERIC L. SCHIELE PHILIP A. GELSTON RICHARD HALL ANDREW J. PITTS RORYO. MILLSON ELIZABETH L. GRAYER WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER MICHAEL T. REYNOLDS FRANCIS P. BARRON JULIE A. -

Snow Patrol Live at Liverpool Echo Arena

May Cover 1:Cover 06/05/2009 16:43 Page 1 May 2009 entertainment, presentation, communication www.lsionline.co.uk Snow Patrol Live at Liverpool Echo Arena PLUS: ProLight&Sound in review; 30 years of EML; the new Hull Truck Theatre; Technical Focus - Chroma-Q’s Color Block 2; Rome’s anniversary projections; Rigging Call; Audio File and more . Kings Place Grand Mosque Visually Richie . BME @ the O2 21st century über-flexibility Lights go on in Abu Dhabi CT’s solution for Lionel Inside the new attraction L&SI has gone digital! Register online FREE at www.lsionline.co.uk/digital Snow Patrol:On tour.qxd 06/05/2009 11:50 Page 28 Snow Patrol Snow Patrol:On tour.qxd 06/05/2009 11:50 Page 29 tour on Snow Patrol’s show at Liverpool’s Echo Arena was evidence of a production in which lighting and video elements work in perfect synchronicity . words & pictures by Steve Moles From production manager down, every crew member I spoke the rebuilt Point is not too bad; parking is restricted, just enough to on this visit mentioned that the band wanted to be ‘more space for four trucks and three buses, but that’s just the limited rock and roll and less pop’. They don’t need to worry: Snow amount of land around the building. The Dublin FOH snake run is bad too, it takes six men about two hours to put the multis in - and if Patrol songs might sing about human emotion, but they’re not it’s a seated show then the FOH position ends up halfway up the love songs in the sense of a three-minute single; think of bleachers.” Leona Lewis’s soaring rendition of ‘Run’ and acknowledge that this was no ordinary pop song, but an almost hymnal This is all useful information: building owners may not like their dirty offering to lift the spirit.