Download This Page As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

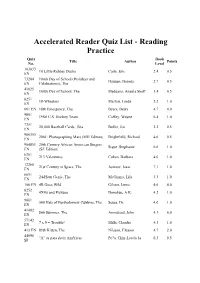

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Biography Artistically Yours

Biography Artistically Yours Nathou, the skater athalie Deschênes put skates on for the first time when she was 9 years old. Her passion for figure skating was immediate. When she was in Secondary “You must always feel Four, she enrolled in a sport-academics program that allowed her to skate more movement, right to your Nfrequently. “If it were not for innocence, we would not be able to create such grand projects.” Everyone had a nickname while on the ice and Nathalie wanted an artist’s name. finger tips.” Out of the blue, her friend Isabelle Brasseur came up with the name Nathou. Since then, the name has followed her everywhere, even on Facebook where, after sharing her thoughts, she signs “Artistically yours . Nathou”. 2 Nathalie Deschênes — Choreographer — www.nathou.net Beautiful and vivacious, she is alive and allows us to experience different emotions . A bright future a rose... Trained by Josée Picard and Eric Gillis, she learned all the basics in order to become to inspire and interpret your a superior athlete. Technical skills, as well choreographies. as presentation and attitude on the ice, were part of Nathalie’s training in order to succeed. She practiced her technique and took 5th place in the junior pairs category at the 1991 Canadian championships. Brasseur and Lloyd Eisler, Josée Chouinard, At the age of 19, she changed trainers and Elvis Stojko and many others. She has also began concentrating on singles skating. skated on the ice while performers from Under the supervision of several trainers, the Cirque du Soleil executed their art. -

Débats Du Sénat

Débats du Sénat re e 1 SESSION . 41 LÉGISLATURE . VOLUME 148 . NUMÉRO 119 COMPTE RENDU OFFICIEL (HANSARD) Le mardi 20 novembre 2012 L'honorable DONALD H. OLIVER Président intérimaire TABLE DES MATIÈRES (L'index quotidien des délibérations se trouve à la fin du présent numéro.) Service des débats : Monique Roy, Édifice national de la presse, pièce 831, tél. 613-992-8143 Centre des publications : David Reeves, Édifice national de la presse, pièce 926, tél. 613-947-0609 Publié par le Sénat Disponible sur Internet : http://www.parl.gc.ca 2819 LE SÉNAT Le mardi 20 novembre 2012 La séance est ouverte à 14 heures, le Président intérimaire étant au Non seulement cette convention reconnaît-elle que les enfants du fauteuil. monde entier jouissent de tous les droits fondamentaux de la personne, mais elle leur confère des droits supplémentaires pour les Prière. protéger, notamment le droit d'être protégés contre l'exploitation, le droit d'avoir des opinions et le droit à l'éducation, aux soins de santé [Traduction] et aux possibilités économiques. DÉCLARATIONS DE SÉNATEURS Cette convention a été signée ou ratifiée par plus de pays que tout autre traité international. À titre de signataire, le Canada s'est engagé à veiller à ce que les enfants soient traités avec dignité et SA MAJESTÉ LA REINE ELIZABETH II ET SON ALTESSE respect. Nous avons pris un engagement au Canada et nous avons ROYALE LE PRINCE PHILIP, DUC D'ÉDIMBOURG pour responsabilité de le remplir, ce qui suppose que nous reconnaissons certains faits troublants concernant les enfants dans FÉLICITATIONS À L'OCCASION DE LEUR SOIXANTE- notre pays. -

Program Assistant Profiles

Important Dates Oct 14—skating as usual on Thanksgiving (am session 7-9) Oct 25- Skate Sharpening Oct 31-Nov 3 Alberta Sectionals Nov 11—skating as usual on Remembrance Day Nov 25—CanSkate Mini Competition We are happy to welcome new CanSkate coaches Megan Jackson and Natalie Schell Program Assistants 2019-20 who have joined returning coach Kristin Raychert in our Learn to Skate program! We also have a great bunch of returning Program Assistants along with many new PA’s who Alexa Saeger-Billling are looking forward to helping out. It’s so exciting to have such a large group of skaters Braya Carroll willing to give back to the club and share their love of skating with new skaters. We Brenna Campbell will introduce a few of our PA’s in each newsletter! Brianna Myhill Elizabeth Murashko Ellie Chuang Program Assistant Profiles Erika West Emerson Flanagan Emma Liew Ethan Cheung Delaney Tacakberry Jane Ashkham Jocelyn McKnight Katherine Li Kaydence Delon Kenzie Davidson Keara Forbes Morgan Jones Natalie Ma Olivia Alcocer Olivia Chen Raya Welch Rylan Vaselenak Yachi Bhojane STARSkate & CompetitiveSkate News It’s hard to believe skaters have been back on the ice for a month Skaters competing @ Sectionals already—time flies when you are having fun! The safety of skaters is our number one priority so while it was unfortunate that the harness Pre-Juvenile U11: Olivia Chen, Justin Cheung, was out of commission for awhile, we are happy to announce that the Emerson Flanagan, Erica Hayman, Reegan Power upgrades will soon be completed. Coaches and skaters are looking forward to using this valuable tool to train jumps once again. -

Viking Voicejan2014.Pub

Volume 2 February 2014 Viking Voice PENN DELCO SCHOOL DISTRICT Welcome 2014 Northley students have been busy this school year. They have been playing sports, performing in con- certs, writing essays, doing homework and projects, and enjoying life. Many new and exciting events are planned for the 2014 year. Many of us will be watching the Winter Olympics, going to plays and con- certs, volunteering in the community, participating in Reading Across America for Dr. Seuss Night, and welcoming spring. The staff of the Viking Voice wishes everyone a Happy New Year. Northley’s Students are watching Guys and Dolls the 2014 Winter Olympics Northley’s 2014 Musical ARTICLES IN By Vivian Long and Alexis Bingeman THE VIKING V O I C E This year’s winter Olympics will take place in Sochi Russia. This is the This year’s school musical is Guy and • Olympic Events first time in Russia’s history that they Dolls Jr. Guys and Dolls is a funny musical • Guys and Dolls will host the Winter Olympic Games. set in New York in the 40’s centering on Sochi is located in Krasnodar, which is gambling guys and their dolls (their girl • Frozen: a review, a the third largest region of Russia, with friends). Sixth grader, Billy Fisher, is playing survey and excerpt a population of about 400,000. This is Nathan Detroit, a gambling guy who is always • New Words of the located in the south western corner of trying to find a place to run his crap game. Year Russia. The events will be held in two Emma Robinson is playing Adelaide, Na- • Scrambled PSSA different locations. -

Sporting Legends: Katerina Witt

SPORTING LEGENDS: KATERINA WITT SPORT: FIGURE SKATING COMPETITIVE ERA: 1979 - 1994 Katarina Witt is a German figure skater. Witt won two Olympic Gold Medals for East Germany, first in the 1984 Sarajevo Olympics and the second in 1988 at the Calgary Olympics. She won the world championships in 1984, 1985, 1987, and 1988. She also won six European championships. Her competitive record makes her one of the most successful figure skaters of all time. Witt was born on December 3, 1965 in Staaken (today part of Berlin, Germany/GDR). She went to school in Karl-Marx-Stadt, today reverted to its pre-Communist name Chemnitz. There she attended a special school for sports-talented children, named Kinder- und Jugendsportschule. She represented the club SC Karl-Marx-Stadt for the GDR (East Germany). Her coach was Jutta Müller since 1970. In 1984 Katarina Witt was voted as “The GDR female athlete of the year” by the readers of the East-German newspaper Junge Welt. In 1987 she recaptured the World Championship title, which she lost in the previous year to Debi Thomas. Many people consider her performance at this event to be the finest of her career. In 1988 Witt started a professional career, which was very unusual for East German athletes. At first she spent three years on tour in the United States with Brian Boitano, also a Gold Medal winner at the Winter Olympics in figure skating. Their show "Witt and Boitano Skating" was so successful that for the first time in ten years New York's Madison Square Garden was sold out for an ice show. -

PRESS RELEASE April 30, 2012

PRESS RELEASE April 30, 2012 For information: Emma Bowie Public Relations Coordinator 613.747.1007 ext. 2547 [email protected] Skate Canada Challenge Returns to Regina for Two More Years OTTAWA, ON: Skate Canada announced today that Regina, Sask., will be the host of the 2013 Skate Canada Challenge and the 2014 Skate Canada Challenge. The 2013 event will take place from December 5-8, 2012 at Co-operators Centre at Evraz Place. The 2014 event will run from December 4-7, 2013. Regina hosted the event for the first time in December of 2011. “We are really looking forward to heading back to Regina for the next two years. Last year the city and Evraz Place were wonderful hosts. It’s a great venue and provides everything we need to host an event of this importance and magnitude,” said William Thompson, Skate Canada CEO. Over 500 skaters will participate in the event. All skaters will have to qualify through their respective sectional championships in order to compete at this event. This is the only opportunity for novice, junior and senior skaters to qualify for the 2013 and then the 2014 Canadian Figure Skating Championships. “Evraz Place, along with its community partners, the Regina Hotel Association and the Regina Opportunities Commission is proud to secure two more years for this major national competition. Hundreds of people from across Canada will come to Regina to experience Regina's warm hospitality, facilities and services. Our new Cooperators Centre has proven to be an ideal venue for multi-arena events like this,” said Mark Allan, President & CEO of Evraz Place. -

Car Lottery Proceeds Support Perley and Rideau Seniors

May 22, 2014 | Keys to Scott-King's convertible go to Almonte man; Car lottery proceeds support Perley and Rideau seniors Submitted Richard Swartman, left, beams after winning a 1988 red convertible once owned by Canadian figure skating champion Barbara Ann Scott-King. Delphine Haslé, development officer with the Perley and Rideau Veterans' Health Centre Foundation, and foundation executive director Daniel Clapin, drew Swartman's ticket in the car lottery fundraiser. Ottawa South News By Erin McCracken An Almonte man is the winner of a 1988 red convertible once owned by Canadian figure skating champion Barbara Ann Scott-King. Richard Swartman's ticket was drawn on May 9 from 1,093 tickets, which each cost $100, in a fundraising lottery organized by The Perley and Rideau Veterans' Health Centre Foundation. The first question Daniel Clapin, foundation executive director, asked Swartman when he called to tell him the news was, do you like the colour red? Swartman had no idea what Clapin was talking about, until the director spelled out the good news. "When we called him from the stage ... you could hear his wife jumping up and down, 'We won a car. We won a car,'" said Clapin. Scott-King's Mercedes Benz 560 SL roadster, valued at $40,000, was donated by Scott-King's husband, Tom King. Proceeds from the event, held in honour of the legendary figure skater's gold-medal performance during the 1948 Olympic Games, will go to The Perley and Rideau's Building Choices, Enriching Lives capital campaign. Scott-King, who passed away in September 2012, joined the campaign that same summer as one of three honourary co-chairs. -

Our Alumni in the News

REUNION EDITION NEWS FROM ICE CAPADES ALUMNI July 2016 Our Alumni in the News Figure Skating Olympic silver medalist Elizabeth Manley shares her story of depression and resilience in Stratford By Laura Cudworth, The Beacon Herald Elizabeth Manley was guest speaker at the annual general meeting of the Stratford General Hospital Foundation this week. Laura Cudworth/The Beacon Herald It was an unforgettable moment for the whole country. Elizabeth Manley skating off the ice wearing a white cowboy hat thrown from the crowd after nailing the long program at the 1988 Olympics in Calgary. An effervescent blonde without an ounce of pretension, she beat out American Debi Thomas for the silver medal in figure skating and nearly knocked East German skater Katarina Witt off the top of the podium. Overall the Calgary Olympics were not the games the country had been hoping for. The games were nearing the end when Manley won the long program. She became Canada's Sweetheart in an instant. “I was an underdog. I wasn’t expected to win a medal. I feel the country was just kind of starting to fade off a little bit and I came out of nowhere and had this amazing skate. It doesn’t matter who I run into today they know exactly where they were sitting at that moment. I even had a lady in labour that held back just so she could see me skate. Some of the stories I’ve heard are just incredible.” But the road to get there was harder than anyone knew. Like all elite athletes she devoted herself to her sport but there were hurdles to overcome that made reaching the top even harder. -

Welcome to the “Barbara Ann Scott: Come Skate with Me” Exhibit Podcast Presented by the City of Ottawa Archives

Welcome to the “Barbara Ann Scott: Come Skate with me” exhibit podcast presented by the city of Ottawa archives. In the podcast, City Archivist Paul Henry interviews Barbara Ann Scott at her home in Florida, and Educational Programming Officer Olga Zeale interviews Paul Henry and Elizabeth Manley in Ottawa. PH: My name is Paul Henry, I am City Archivist for the City of Ottawa. OZ: Why was it important for the City of Ottawa Archives to acquire Barbara Ann Scott’s collection? PH: Uh, well the mandate of the City of Ottawa Archives is to document the corporation of the City of Ottawa as well as serve as a repository for records that would otherwise be lost to history; records that in particular tell the story of the individual contributions of notable citizens, organizations, businesses, community organizations, that have contributed to the fabric of Ottawa and which tell, essentially, the story of the gap between what the City does and what our known history of an area is. So, the private records really flush out and make interesting a story of Ottawa beyond its role as a nation‟s capital. The Barbara Ann Scott collection fulfills that in many ways. Barbara is our most decorated citizen, our most decorated Olympic athlete, and if you think back to those days in „47 and „48 when we had, and gave Barbara the key to the city and had events and parades in her honour. The number of people that came out in those days to celebrate her accomplishments was certainly something, and in many ways, the city, in some way belongs to Barbara. -

February 1, 1957

Te::nple Beth El 10 70 Orchard Ava. Providence• B. 1. To Hold Israel Bond Drive Honoring Cantors 65th Birthday A special na,tional drive in cele leaders of the Providence Israel bra.tion of Eddie cant.or's 65th Bond Committee a,ttended a lWl birthday was announced toda.y by cheon meeting 3ast WednesdaY the State of Lsrael Bond drive. (January 23l - and heard, on a The special campaign in honor closed circwt telephone confureBee.. of the noted entertainer who has Foreign Mmister Golda Meir :and VOL. XL, No. 47 been a leading personality in work Ambassador Abba Eba:n gjve a for lsrael for many years, will confiden tial report on the critical highlight Providence's intensive political and economk problems effort. to provide the Israel Bond confronting Israel and the dire Israel Insists Egypt End dollars needed to maintain Israel's need for Bond dollars to shore up .roonomic strength during the Israel's economy dming tJ:ns criti presen.t Middle Eastern crisis. cal period_ A total of S1'7,500 in The Providence effort is part of Bonds v.ere purchased by those in a nation- wide campaign to sell a attendance, renelring their mem Blockade, Live Up to Pact minimum of S75,000.000 in l:srael bership in the Guardians of Israel Bonds during 1957. The first and Na.tionai Sponsors. The Com NEW YORK - Israel insisted~---- - ----- ------ ------------ S20,000,000 of this sum must be mlttee decided to immroiately"'elll this week that "effective guaran raised before the end of February, bark on a drive to re-enroll and tees" must be obtained from to meet Israel's pressing need. -

Adream Season

EVGENIA MEDVEDEVA MOVES TO CANADIAN COACH ALJONA SAVCHENKO KAETLYN BRUNO OSMOND MASSOT TURN TO A DREAM COACHING SEASON MADISON CHOCK & SANDRA EVAN BATES GO NORTH BEZIC OF THE REFLECTS BORDER ON HER CREATIVE CAREER Happy family: Maxim Trankov and Tatiana Volosozhar posed for a series of family photos with their 1-year-old daughter, Angelica. Photo: Courtesy Sergey Bermeniev Adam Rippon and his partner Jena Johnson hoisted their Mirrorball Trophies after winning “Dancing with the Stars: Athlete’s Edition” in May. Photo: Courtesy Rogers Media/CityTV Contents 24 Features VOLUME 23 | ISSUE 4 | AUGUST 2018 EVGENIA MEDVEDEVA 6 Feeling Confident and Free MADISON CHOCK 10 & EVAN BATES Olympic Redemption A CREATIVE MIND 14 Canadian Choreographer Sandra Bezic Reflects on Her Illustrious Career DIFFERENT DIRECTIONS 22 Aljona Savchenko and Bruno Massot Turn to Coaching ON THE KAETLYN OSMOND COVER Ê 24 Celebrates a Dream Season OLYMPIC INDUCTIONS 34 Champions of the Past Headed to Hall of Fame EVOLVING ICE DANCE HUBS 38 Montréal Now the Hot Spot in the Ice Dance World THE JUNIOR CONNECTION 40 Ted Barton on the Growth and Evolution of the Junior Grand Prix Series Kaetlyn Osmond Departments 4 FROM THE EDITOR 44 FASHION SCORE All About the Men 30 INNER LOOP Around the Globe 46 TRANSITIONS Retirements and 42 RISING STARS Coaching Changes NetGen Ready to Make a Splash 48 QUICKSTEPS COVER PHOTO: SUSAN D. RUSSELL 2 IFSMAGAZINE.COM AUGUST 2018 Gabriella Papadakis drew the starting orders for the seeded men at the French Open tennis tournament, and had the opportunity to meet one of her idols, Rafael Nadal.