Habitat Use and Movement Patterns in the Endangered Ground Beetle Species, Carabus Olympiae (Coleoptera: Carabidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Factors Affecting the Diversity of Sphagnum Cover Inhabitants with the Focus on Ground Beetle Assemblages in Central-Eastern European Peat Bogs

COMMUNITY ECOLOGY 20(1): 45-52, 2019 1585-8553 © AKADÉMIAI KIADÓ, BUDAPEST DOI: 10.1556/168.2019.20.1.5 Key factors affecting the diversity of Sphagnum cover inhabitants with the focus on ground beetle assemblages in Central-Eastern European peat bogs G. Sushko Department of Ecology and Environmental Protection, Vitebsk State University P. M. Masherov, Moskovski Ave. 33, 21008 Vitebsk, Belarus. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Belarus, Carabidae, diversity, environmental factors, Sphagnum dwellers. Abstract. A key structural component in peat bog formation is Sphagnum spp., which determines very specific associated envi- ronmental conditions. The aim of this study was to characterise some of the key factors affecting the diversity, species richness and abundance of sphagnum inhabiting ground beetles and to examine the maintenance of stable populations of cold adapted specialised peat bog species. A total of 52 carabid species were recorded by pitfall traps along six main habitats, such as the lagg zone, pine bog, hollows, hummock open bog and dome. The results are characterised by a low diversity, which vary significantly among habitat types, and include a high abundance of a few carabid species. Among the variables influencing carabid species richness and abundance were plant cover, pH and the conductivity of the Sphagnum mat water. Vascular plant cover was a key factor shaping carabid beetle assemblages in the slope and the dome, while electric conductivity affected carabid beetle assem- blage in the lagg. Whereas, the water level was the most important factor for the hollows. At the same time, peat bog specialists showed low sensitivity to the gradient of the analysed variables. -

Microhabitat Mosaics Are Key to the Survival of an Endangered Ground Beetle (Carabus Nitens) in Its Post-Industrial Refugia

Journal of Insect Conservation (2018) 22:321–328 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-018-0064-x ORIGINAL PAPER Microhabitat mosaics are key to the survival of an endangered ground beetle (Carabus nitens) in its post-industrial refugia Martin Volf1,2 · Michal Holec3 · Diana Holcová3 · Pavel Jaroš4 · Radek Hejda5 · Lukáš Drag1 · Jaroslav Blízek6 · Pavel Šebek1 · Lukáš Čížek1,7 Received: 12 September 2017 / Accepted: 27 April 2018 / Published online: 3 May 2018 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Biota dependant on early seral stages or frequently disturbed habitats belong to the most rapidly declining components of European biodiversity. This is also the case for Carabus nitens, which is threatened across Western and Central Europe. We studied one of the last remaining populations of this ground beetle in the Czech Republic, which inhabits post-extraction peat bogs. In line with findings from previous studies, we show that C. nitens prefers patches characterized by higher light intensity and lower vegetation cover. Abundance of females was positively correlated with the cover of plant species requir- ing higher temperature. In addition, we demonstrate its preference for periodically moist, but not wet or inundated plots, suggesting that the transition between dry heathland and wet peat bog might be the optimal habitat for this species. This hypothesis is further supported by results showing a positive correlation between the abundance of C. nitens and vegetation cover comprising of a mix of species typical for heathland, peat bog, and boreal habitats. Our results show that C. nitens mobility is comparable to other large wingless carabids. -

Biller (Coleoptera) Fra Skallingen

Biller (Coleoptera) fra Skallingen VIGGO MARLER Mah1er, V.: Co1eoptera from the Skallingen Peninsu1a, Western coast of Jut1and, Den mark. Ent. Meddr 54: 39-61 - Copenhagen, Denmark 1987. ISSN 0013-8851. 732 species of Co1eoptera have been found at the Skallingen Peninsu1a on the western coast of Jutland. Of these, Ochthephilurn collare is new to the Danish fauna. The spe cies have been re1ated to the ditTerent habitats of Skallingen, and comments are given on a number o finteresting species. Viggo Mah1er, Steen Billes Torv 8, 3. th., 8200 Århus N, Denmark. Undersøgelser over Skallingens bille Indsamlingsmetoder fauna De fleste biller er mere stationære og med længere levetid som voksne end mange Kendskabet til Skallingens billefauna star andre insektgrupper. Det er derfor oftest me ter i 1930'erne med Ellinor Bro Larsens re lønsomt at opsøge dem, enten på deres fremragende biologiske studier af de tunnel levesteder om sommeren eller i vinterkvar gravende biller (Larsen 1936), hvori biolo tererne, end at lokke dem til sig. På Skallin gien og forekomsten på Skallingen indgåen• gen har lokning kun været brugt enkelte gan de er behandlet for slægterne Dyschirius, ge til billefangst Dicheirotrichus, Ochthebius, Carpelimus, Lyslokmng har bl.a. giVet Arhopalus Bledius, Diglotta og Heterocerus og for rusticus ogferus. Udlægning af fugle- og pat arterne Rembidion pallidipenne, varium og tedyrådsler på sandbund har den ulempe, at laterale og Acrotona exigua. det er svært at tøjre dem så grundigt, at ræve I de følgende år foretog Ferdinand Larsen ikke kan grave dem fri, men de gange, det er nogle få indsamlingsture til Skallingen, og i lykkedes, har det givet adskillige arter af 1950'erne blev området undersøgt af Frits Aleochariner foruden Cataps chrysomeloi Bangsholt, Hans Gønget, Victor Hansen og des og Dermestes murinus samt Trox hispi Uffe Kornerup, således at Bangsholt kunne dus. -

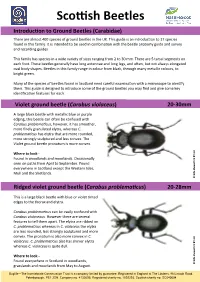

Scottish Beetles Introduction to Ground Beetles (Carabidae) There Are Almost 400 Species of Ground Beetles in the UK

Scottish Beetles Introduction to Ground Beetles (Carabidae) There are almost 400 species of ground beetles in the UK. This guide is an introduction to 17 species found in this family. It is intended to be used in combination with the beetle anatomy guide and survey and recording guides. This family has species in a wide variety of sizes ranging from 2 to 30 mm. There are 5 tarsal segments on each foot. These beetles generally have long antennae and long legs, and often, but not always elongated oval body shapes. Beetles in this family range in colour from black, through many metallic colours, to bright green. Many of the species of beetles found in Scotland need careful examination with a microscope to identify them. This guide is designed to introduce some of the ground beetles you may find and give some key identification features for each. Violet ground beetle (Carabus violaceus) 20-30mm A large black beetle with metallic blue or purple edging, this beetle can often be confused with Carabus problematicus, however, it has smoother, more finely granulated elytra, whereas C. problematicus has elytra that are more rounded, more strongly sculptured and less convex. The Violet ground beetle pronotum is more convex. Where to look - Found in woodlands and moorlands. Occasionally seen on paths from April to September. Found everywhere in Scotland except the Western Isles, Mull and the Shetlands. BY 2.0 CC Shcmidt © Udo Ridged violet ground beetle (Carabus problematicus) 20-28mm This is a large black beetle with blue or violet tinted edges to the thorax and elytra. -

Systematic and Abundance of Ground Beetles (Carabidae: Coleoptera) from District Poonch Azad Kashmir, Pakistan

IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) e-ISSN: 2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372. Volume 6, Issue 2 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 24-29 www.iosrjournals.org Systematic and Abundance of Ground Beetles (Carabidae: Coleoptera) From District Poonch Azad Kashmir, Pakistan Junaid Rahim¹, Muhammad Rafique Khan², Naila Nazir³ 1²³4Department of Entomology, University of Poonch Rawalakot, Azad Jammu Kashmir, Pakistan Abstract: Present study was conducted during 2010- 2012 dealing with the exploration of carabid fauna and study of their systematic from district Poonch of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Carabid beetles were collected with the help of pitfall traps and identified up to specie level with the help of available literature. We identified five species under three genera belonging to 3 sub-families. These sub families are Licininae, Carabinae, Brachininae and the species are Carabus caschmirensis, Chlaenius quadricolar, Pheropsophus sobrinus, Chlaenius laticollis, and Chlaenius hamifer. Carabus cashmirensis was the most abundant species. It was followed by Chlaenius quadricolar, Pheropsophus sobrinus, Chlaenius laticollis, and Chlenius hamifer. Key words: Abundant, Bio-indicator, Carabidae, Poonch, Systematics I. Introduction Poonch district is of subtropical high land type to temperate area of southern Azad Kashmir receives an average rainfall of 1400 – 1800mm annually. The temperature ranges from 2C˚ to 38C˚ during extreme winter it falls below 0C˚. Some of major plants as apple, some citrus, walnut, apricot and many others along with thick mixed forests of evergreen pine, deodar, blue pine cedar trees and fir are present in study area. Surveyed area hosts the family Carabidae while an estimation of 40,000 species throughout the world [1]. -

(Coleoptera: Carabidae) and Habitat Fragmentation

REVIEW Eur. J.Entomol. 98: 127-132, 2001 ISSN 1210-5759 Carabid beetles (Coleóptera: Carabidae) and habitat fragmentation: a review Ja r i NIEMELÁ Department ofEcology and Systematics, PO Box 17, FIN-00014 University ofHelsinki, Finland e-mail:[email protected] Key words. Carabids, conservation, dispersal, forests, habitat fragmentation, habitat heterogeneity, metapopulations, species richness, generalists, specialists Abstract. I review the effects of habitat fragmentation on carabid beetles (Coleoptera, Carabidae) and examine whether the taxon could be used as an indicator of fragmentation. Related to this, I study the conservation needs of carabids. The reviewed studies showed that habitat fragmentation affects carabid assemblages. Many species that require habitat types found in interiors of frag ments are threatened by fragmentation. On the other hand, the species composition of small fragments of habitat (up to a few hec tares) is often altered by species invading from the surroundings. Recommendations for mitigating these adverse effects include maintenance of large habitat patches and connections between them. Furthermore, landscape homogenisation should be avoided by maintaining heterogeneity ofhabitat types. It appears that at least in the Northern Hemisphere there is enough data about carabids for them to be fruitfully used to signal changes in land use practices. Many carabid species have been classified as threatened. Mainte nance of the red-listed carabids in the landscape requires species-specific or assemblage-specific measures. INTRODUCTION HABITAT FRAGMENTATION AND CARABID ASSEMBLAGES Destruction and fragmentation of habitats, overkill, introduction of alien species, and cascading effects of Effects of fragmentation on carabid assemblages species extinctions have been labelled the “evil quartet”, Habitat fragmentation is the partitioning of a con i.e. -

Geographic Variation in the African-Iberian Ground

Graellsia, 51: 27-35 (1995) GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION IN THE AFRICAN- IBERIAN GROUND BEETLE RHABDOTOCARABUS MELANCHOLICUS (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) AND ITS TAXONOMICAL AND BIOGEOGRAPHICAL IMPLICATIONS M. García-París (*, **) & M. París (**) ABSTRACT A study of morphological variation among populations from southern Spain and northwestern Africa of Rhabdotocarabus melancholicus (Fabricius, 1798) shows that there is statistical support for the recognition of three taxa: R. m. submeridionalis (Breuning, 1975) distributed over southeastern Spain, R. m. dehesicola n. ssp. from southwestern Spain and southern Portugal and R. m. melancholicus geographically res- tricted to northwestern Africa. This new arrangement changes previous biogeographic pictures for the genus, since R. m. melancholicus is not present in Europe and the range of variation observed within Iberian R. melancholicus is increased with new endemic taxa. We propose that the current differentiation among taxa is the result of successive vicariance events caused by dramatic paleogeographic changes which have occurred in the western Mediterranean region since the Mio-Pliocene boundary. Key words: Coleoptera, Carabidae, morphological variation, Biogeography, Mediterranean region. RESUMEN Variación geográfica en el carábido íbero-africano Rhabdotocarabus melancholicus (Coleoptera: Carabidae) y sus implicaciones taxonómicas y biogeográficas Un estudio de la variación morfológica de poblaciones del sur de España y del noroes- te de África de Rhabdotocarabus melancholicus (Fabricius, 1798) permite reconocer esta- dísticamente la existencia de dos taxa en las porciones meridionales de la Península Ibérica: R. m. submeridionalis (Breuning, 1975) distribuido por la región suroriental ibéri- ca y R. m. dehesicola n. ssp. del suroeste de España y sur de Portugal; un tercer taxon, R. m. melancholicus, antes incluido en la fauna ibérica se considera ahora exclusivo del noro- este de África. -

Mixed Species Forests Risks, Resilience and Managementt Program and Book of Abstracts

Mixed species forests risks, resilience and managementt Program and book of abstracts Lund, Sweden Conference cancelled25 - 27 march 2020 due to the corona crisis Report 54, Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre Mixed Species Forests: Risks, Resilience and Management 25-27 March 2020, Lund, Sweden Organizing committee Magnus Löf, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Sweden Jorge Aldea, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Sweden Ignacio Barbeito, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Sweden Emma Holmström, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Sweden Science committee Assoc. Prof Anna Barbati, University of Tuscia, Italy Prof Felipe Bravo, ETS Ingenierías Agrarias Universidad de Valladolid, Spain Senior researcher Andres Bravo-Oviedo, National Museum of Natural Sciences, Spain Senior researcher Hervé Jactel, Biodiversité, Gènes et Communautés, INRA Paris, France Prof Magnus Löf, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Sweden Prof Hans Pretzsch, Technical University of Munich, Germany Senior researcher Miren del Rio, Spanish Institute for Agriculture and Food Research and Technology (INIA)-CIFOR, Spain Involved IUFRO units and other networks SUMFOREST ERA-Net research project Mixed species forest management: Lowering risk, increasing resilience IUFRO research groups 1.09.00 Ecology and silviculture of mixed forests and 7.03.00 Entomology IUFRO working parties 1.01.06 Ecology and silviculture of oak, 1.01.10 Ecology and silviculture of pine and 8.02.01 Key factors and ecological functions for forest biodiversity Acknowledgements The conference was supported from the organizing- and scientific committees, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre and Akademikonferens. Several research networks have greatly supported the the conference. The IUFRO secretariat helped with information and financial support was grated from SUMFOREST ERA-Net. -

Measuring Genome Sizes Using Read-Depth, K-Mers, and Flow Cytometry: Methodological Comparisons in Beetles (Coleoptera)

G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics Early Online, published on June 29, 2020 as doi:10.1534/g3.120.401028 1 Measuring genome sizes using read-depth, k-mers, and flow 2 cytometry: methodological comparisons in beetles (Coleoptera) 3 James M. Pflug,*, Valerie Renee Holmes,† Crystal Burrus,† J. Spencer Johnston,† and David R. 4 Maddison* 5 6 *Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 7 †Department of Entomology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 8 1 Corresponding author: 3029 Cordley Hall, Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 USA. E-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2020. Published by the Genetics Society of America. 2 9 Abstract 10 Measuring genome size across different species can yield important insights into 11 evolution of the genome and allow for more informed decisions when designing next-generation 12 genomic sequencing projects. New techniques for estimating genome size using shallow 13 genomic sequence data have emerged which have the potential to augment our knowledge of 14 genome sizes, yet these methods have only been used in a limited number of empirical studies. In 15 this project, we compare estimation methods using next-generation sequencing (k-mer methods 16 and average read depth of single-copy genes) to measurements from flow cytometry, a standard 17 method for genome size measures, using ground beetles (Carabidae) and other members of the 18 beetle suborder Adephaga as our test system. We also present a new protocol for using read- 19 depth of single-copy genes to estimate genome size. -

© 2016 David Paul Moskowitz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2016 David Paul Moskowitz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE LIFE HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE TIGER SPIKETAIL DRAGONFLY (CORDULEGASTER ERRONEA HAGEN) IN NEW JERSEY By DAVID P. MOSKOWITZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Entomology Written under the direction of Dr. Michael L. May And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION THE LIFE HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE TIGER SPIKETAIL DRAGONFLY (CORDULEGASTER ERRONEA HAGEN) IN NEW JERSEY by DAVID PAUL MOSKOWITZ Dissertation Director: Dr. Michael L. May This dissertation explores the life history and behavior of the Tiger Spiketail dragonfly (Cordulegaster erronea Hagen) and provides recommendations for the conservation of the species. Like most species in the genus Cordulegaster and the family Cordulegastridae, the Tiger Spiketail is geographically restricted, patchily distributed with its range, and a habitat specialist in habitats susceptible to disturbance. Most Cordulegastridae species are also of conservation concern and the Tiger Spiketail is no exception. However, many aspects of the life history of the Tiger Spiketail and many other Cordulegastridae are poorly understood, complicating conservation strategies. In this dissertation, I report the results of my research on the Tiger Spiketail in New Jersey. The research to investigate life history and behavior included: larval and exuvial sampling; radio- telemetry studies; marking-resighting studies; habitat analyses; observations of ovipositing females and patrolling males, and the presentation of models and insects to patrolling males. -

Chemical Compounds Related to the Predation Risk Posed by Malacophagous Ground Beetles Alter Self-Maintenance Behavior of Naive Slugs (Deroceras Reticulatum)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Archive Toulouse Archive Ouverte Open Archive TOULOUSE Archive Ouverte (OATAO) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author-deposited version published in : http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID : 16317 To link to this article : DOI :10.1371/journal.pone.0079361 URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079361 To cite this version : Bursztyka, Piotr and Saffray, Dominique and Lafont-Lecuelle, Céline and Brin, Antoine and Pageat, Patrick Chemical compounds related to the predation risk posed by malacophagous ground beetles alter self-maintenance behavior of naive slugs (Deroceras reticulatum). (2013) PLoS ONE, vol. 8 (n° 11). pp. 1-11. ISSN 1932-6203 Any correspondance concerning this service should be sent to the repository administrator: [email protected] Chemical Compounds Related to the Predation Risk Posed by Malacophagous Ground Beetles Alter Self- Maintenance Behavior of Naive Slugs (Deroceras reticulatum) Piotr Bursztyka1,2*, Dominique Saffray1, Ce´line Lafont-Lecuelle1, Antoine Brin2, Patrick Pageat1 1 Department Agronomy-Aquaculture, Research Institute in Semiochemistry and Applied Ethology, Saint-Saturnin-le`s-Apt, Vaucluse, France, 2 Biodiversite´ des Syste`mes Agricoles et Naturels UMR 1201 Dynafor, Engineering School of Purpan, Toulouse, Haute-Garonne, France Abstract Evidence that terrestrial gastropods are able to detect chemical cues from their predators is obvious yet scarce, despite the scientific relevance of the topic to enhancing our knowledge in this area. -

Crveni Popis Trčaka Hrvatske (Coleoptera, Carabidae) Naručitelj: Državni Zavod Za Zaštitu Prirode

CRVENI POPIS TRČAKA HRVATSKE (COLEOPTERA, CARABIDAE) NARUČITELJ: DRŽAVNI ZAVOD ZA ZAŠTITU PRIRODE 2007. CRVENI POPIS TRČAKA (CARABIDAE) HRVATSKE Crveni popis trčaka (Carabidae) izrađen je na prijedlog Državnog zavoda za zaštitu prirode. Crveni popisi raznih skupina su jedna od temeljnih stručnih podloga u zaštiti prirode (Radović 2004). Njihova je zadaća prikazati koje vrste su u opasnosti od izumiranja i koliko brzo se to može očekivati. Za izradu takvih popisa postoje određeni preduvjeti, odnosno količina znanja proizašla iz istraživanja određene skupine mora biti dostatna. ŠTO SU SVE TRČCI ? Trčci (Carabidae) su jedna od najvećih porodica kornjaša (Coleoptera). Kako je sistematika ove porodice predmet stalnih istraživanja i promjena, procjena ukupnog broja vrsta u svijetu, ali i u Europi varira kod različitih autora. Osim toga, usprkos dva stoljeća intenzivnih istraživanja, autori se još ne slažu oko toga koje sve vrste pripadaju porodici Carabidae, niti kako je ona podijeljena na niže sistematske kategorije. U najstarijim katalozima porodica Carabidae je podijeljena, većinom, samo na dvije do tri potporodice. Ti katalozi (Dejean 1831, Ganglbauer 1892, Junk & Shlenking 1926, Latreille 1802, 1810, Schaum 1850, Winkler 1924-1932) napravljeni su na temelju ondašnjih znanja, a to je u najvećoj mjeri bilo samo poznavanje i uspoređivanje morfologije odraslih jedinki. U radovima nešto novijeg datuma (Basilewski 1973, Jeannel 1941-1942) porodica trčaka promatrana je također s aspekta morfologije imaga, ali je podijeljena na veći broj, često i preko 50 potporodica. Lindroth (1961-1962) je broj potporodica smanjio na 8, ali ih je podijelio na nekoliko desetaka tribusa koji međusobno nisu ujedinjeni. Te tribuse je u supertribuse ujedinio Kryzhanovskij (1983), a tu podjelu prihvaćao je veliki broj autora.