Edith Cavell's Life and Death in Anglo-American Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RCN History of Nursing Society Newsletter

HISTORY OF NURSING SOCIETY Spring 2016 History of Nursing Society newsletter Contents HoNS round-up P2 Cooking up a storm P4 Nurses’ recipes from the past RCN presidents P5 A history of the College’s figureheads Mary Frances Crowley P6 An Irish nursing pioneer Northampton hospital P7 The presidents’ exhibition A home for nurses at RCN headquarters Book reviews P8 A centenary special Welcome to the spring 2016 issue of the RCN History of Nursing Society Something to say? (HoNS) newsletter Send contributions for It can’t have escaped your attention that the RCN is celebrating its centenary this year and the the next newsletter to HoNS has been actively engaged in the preparations. We will continue to be involved in events the editor: and exhibitions as the celebrations progress over the next few months. Dianne Yarwood The centenary launch event took place on 12 January and RCN Chief Executive Janet Davies and President Cecilia Anim said how much they were looking forward to the events of the year ahead. A marching banner, made by members of the Townswomen’s Guilds, was presented to the College (see p2). The banner will be taken to key RCN events this year, including Congress, before going on permanent display in reception at RCN headquarters in London. The launch event also saw the unveiling of the RCN presidents’ exhibition, which features photographs of each president and short biographical extracts outlining their contributions to the College (see p5). There was much interest in the new major exhibition in the RCN Library and Heritage Centre. The Voice of Nursing explores how nursing has changed over the past 100 years by drawing on stories and experiences of members and items and artefacts from the RCN archives. -

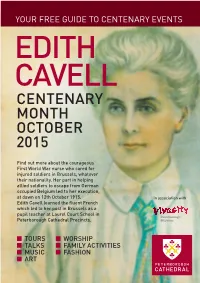

Edith Cavell Centenary Month October 2015

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO CENTENARY EVENTS EDITH CAVELL CENTENARY MONTH OCTOBER 2015 Find out more about the courageous First World War nurse who cared for injured soldiers in Brussels, whatever their nationality. Her part in helping allied soldiers to escape from German occupied Belgium led to her execution, at dawn on 12th October 1915. In association with Edith Cavell learned the fluent French which led to her post in Brussels as a pupil teacher at Laurel Court School in Peterborough Peterborough Cathedral Precincts. MusPeeumterborough Museum n TOURS n WORSHIP n TALKS n FAMILY ACTIVITIES n MUSIC n FASHION n ART SATURDAY 10TH OCTOBER FRIDAY 9TH OCTOBER & SUNDAY 11TH OCTOBER Edith Cavell Cavell, Carbolic and A talk by Diana Chloroform Souhami At Peterborough Museum, 7.30pm at Peterborough Priestgate, PE1 1LF Cathedral Tours half hourly, Diana Souhami’s 10.00am – 4.00pm (lasts around 50 minutes) biography of Edith This theatrical tour with costumed re-enactors Cavell was described vividly shows how wounded men were treated by The Sunday Times during the Great War. With the service book for as “meticulously a named soldier in hand you will be sent to “the researched and trenches” before being “wounded” and taken to sympathetic”. She the casualty clearing station, the field hospital, will re-tell the story of Edith Cavell’s life: her then back to England for an operation. In the childhood in a Norfolk rectory, her career in recovery area you will learn the fate of your nursing and her role in the Belgian resistance serviceman. You will also meet “Edith Cavell” and movement which led to her execution. -

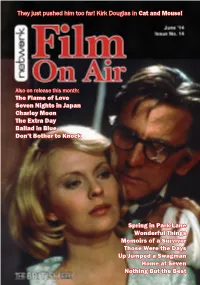

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Edith Cavell Fact Sheet

Edith Cavell Fact Sheet Edith Cavell (1865-1915) was a British nurse working in Belgium who was executed By the Germans on a charge of assisting British and French prisoners to escape during the First World War. Born on 4 DecemBer 1865 in Norfolk, Cavell started nursing aged 20. After many nursing joBs Cavell moved to Beligum and was appointed matron of the Berkendael Medical Institute in 1907. At the start of the First World War in 1914 and the following German occupation of Belgium, Cavell joined the Red Cross supporting the nursing effort and the The Berkendael Institute, where Cavell was matron, was converted into a hospital for wounded soldiers of all nationalities. Soldiers who were treated at Berkendael afterwards succeeded in escaping with Cavell’s active assistance to neutral Holland. After Being Betrayed, Cavell was arrested on 5 August 1915 By local German authorities and charged with personally aiding the escape of some 200 soldiers. Once arrested, Cavell was kept in solitary confinement for nine weeks where the German forces successfully took a confession from Cavell which formed the Basis of her trial. Cavell along with a named Belgian accomplice Philippe Baucq, were pronounced guilty and sentenced to death By German firing squad. The sentence was carried out on 12 OctoBer 1915 without reference to the German high command. Cavell’s case received significant sympathetic worldwide press coverage and propaganda, most notably in Britain and the then-neutral United States. New’s of Cavell’s murder was used as propaganda to support the war effort. In the weeks after Cavell’s death the numBer of young men enlisting to serve in the First World War significantly increased. -

Spring 2011 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 65 Spring 2011 Issn 1476-6760 Christine Hallett on Historical Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Nursing Karen Nolte on the Relationship between Doctors and Nurses in Agnes Karll’s Letters Dian L. Baker, May Ying Ly, and Colleen Marie Pauza on Hmong Nurses in Laos during America’s Secret War, 1954- 1974 Elisabetta Babini on the Cinematic Representation of British Nurses in Biopics Anja Peters on Nanna Conti – the Nazis’ Reichshebammenführerin Lesley A. Hall on finding female healthcare workers in the archives Plus Four book reviews Committee news www.womenshistorynetwork.org 9 – 11 September 2011 20 Years of the Women’s History Network Looking Back - Looking Forward The Women’s Library, London Metropolitan University Keynote Speakers: Kathryn Gleadle, Caroline Bressey Sheila Rowbotham, Sally Alexander, Anna Davin Krista Cowman, Jane Rendall, Helen Meller The conference will look at the past 20 years of writing women’s history, asking the question where are we now? We will be looking at histories of feminism, work in progress, current areas of debate such as religion and perspectives on national and international histories of the women’s movement. The conference will also invite users of The Women’s Library to take part in one strand that will be set in the Reading Room. We would very much like you to choose an object/item, which has inspired your writing and thinking, and share your experience. Conference website: www.londonmet.ac.uk/thewomenslibrary/ aboutthecollections/research/womens-history-network-conference-2011.cfm Further information and a conference call will be posted on the WHN website www.womenshistorynetwork.org Editorial elcome to the spring issue of Women’s History This issue, as usual, also contains a collection of WMagazine. -

![Edit] 17Th Century](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4388/edit-17th-century-374388.webp)

Edit] 17Th Century

Time line 16th century y 1568 - In Spain. The founding of the Obregones Nurses "Poor Nurses Brothers" by Bernardino de Obregón / 1540-1599. Reformer of spanish nursing during Felipe II reign. Nurses Obregones expand a new method of nursing cares and printed in 1617 "Instrucción de Enfermeros" ("Instruction for nurses"), the first known handbook written by a nurse Andrés Fernández, Nurse obregón and for training nurses. [edit] 17th century St. Louise de Marillac Sisters of Charity y 1633 ± The founding of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, Servants of the Sick Poor by Sts. Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac. The community would not remain in a convent, but would nurse the poor in their homes, "having no monastery but the homes of the sick, their cell a hired room, their chapel the parish church, their enclosure the streets of the city or wards of the hospital." [1] y 1645 ± Jeanne Mance establishes North America's first hospital, l'Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal. y 1654 and 1656 ± Sisters of Charity care for the wounded on the battlefields at Sedan and Arras in France. [2] y 1660 ± Over 40 houses of the Sisters of Charity exist in France and several in other countries; the sick poor are helped in their own dwellings in 26 parishes in Paris. [edit] 18th century y 1755 ± Rabia Choraya, head nurse or matron in the Moroccan Army. She traveled with Braddock¶s army during the French & Indian War. She was the highest-paid and most respected woman in the army. y 1783 ± James Derham, a slave from New Orleans, buys his freedom with money earned working as a nurse. -

Nhs Lambeth Ccg; Invoices Paid Over £25,000 June 2019

NHS LAMBETH CCG; INVOICES PAID OVER £25,000 JUNE 2019 46,721,675.21 Entity Date Expense Type Expense area Supplier AP Amount (£) Purchase invoice number NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Meeting expense/Room Hire PROGRAMME PROJECTS ABBEY COMMUNITY SERVICES LTD 1,043.60 7362 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Public Relations Expenses PROGRAMME PROJECTS ABBEY COMMUNITY SERVICES LTD 200.40 7362 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Meeting expense/Room Hire PROGRAMME PROJECTS KINGS COLLEGE LONDON 298.00 KX44491 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Contract & Agency-Agency A & C PROGRAMME PROJECTS HAYS SPECIALIST RECRUITMENT LTD 619.73 1009472001 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 External Contractors PROGRAMME PROJECTS HAYS SPECIALIST RECRUITMENT LTD 338.47 1009472001 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 External Contractors PROGRAMME PROJECTS FRESH EGG LTD 8,333.33 27693 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Computer Hardware Purch PRIMARY CARE IT DELL CORPORATION LTD 24,336.00 7402518037 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Computer Hardware Purch PRIMARY CARE DEVELOPMENT DELL CORPORATION LTD 7,215.00 7402523057 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 External Contractors PROGRAMME PROJECTS 2020 DELIVERY LTD 41,383.87 4169 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Other Gen Supplies & Srv PROGRAMME PROJECTS 2020 DELIVERY LTD 1,338.01 4169 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Hcare Srv Rec Fdtn Trust-Contract Baseline ACUTE COMMISSIONING GUYS & ST THOMAS HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 10,169,963.00 3264009 NHS Lambeth CCG 30/06/2019 Hcare Srv Rec Fdtn Trust-Contract Baseline COMMUNITY SERVICES GUYS & ST THOMAS HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 3,770,488.33 -

Search Titles and Presenters at Past AAHN Conferences from 1984

American Association for the History of Nursing, Inc. 10200 W. 44th Avenue, Suite 304 Wheat Ridge, CO 80033 Phone: (303) 422-2685 Fax: (303) 422-8894 [email protected] www.aahn.org Titles and Presenters at Past AAHN Conferences 1984 – 2010 Papers remain the intellectual property of the researchers and are not available through the AAHN. 2010 Co-sponsor: Royal Holloway, University of London, England September 14 - 16, 2010 London, England Photo Album Conference Podcasts The following podcasts are available for download by right-clicking on the talk required and selecting "Save target/link as ..." Fiona Ross: Conference Welcome [28Mb-28m31s] Mark Bostridge: A Florence Nightingale for the 21st Century [51Mb-53m29s] Lynn McDonald: The Nightingale system of training and its influence worldwide [13Mb-13m34s] Carol Helmstadter: Nightingale Training in Context [15Mb-16m42s] Judith Godden: The Power of the Ideal: How the Nightingale System shaped modern nursing [17Mb-18m14s] Barbra Mann-Wall: Nuns, Nightingale and Nursing [15Mb-15m36s] Dr Afaf Meleis: Nursing Connections Past and Present: A Global Perspective [58Mb-61m00s] 2009 Co-sponsor: School of Nursing, University of Minnesota September 24 - 27, 2009 Minneapolis, Minnesota Paper Presentations Protecting and Healing the Physical Wound: Control of Wound Infection in the First World War Christine Hallett ―A Silent but Serious Struggle Against the Sisters‖: Working-Class German Men in Nursing, 1903- 1934 Aeleah Soine, PhDc The Ties that Bind: Tale of Urban Health Work in Philadelphia‘s Black Belt, 1912-1922 J. Margo Brooks Carthon, PhD, RN, APN-BC The Cow Question: Solving the TB Problem in Chicago, 1903-1920 Wendy Burgess, PhD, RN ―Pioneers In Preventative Health‖: The Work of The Chicago Mts. -

Gordon Mccallum (Sound Engineer) 26/5/1919 - 10/9/1989 by Admin — Last Modified Jul 27, 2008 02:38 PM

Gordon McCallum (sound engineer) 26/5/1919 - 10/9/1989 by admin — last modified Jul 27, 2008 02:38 PM BIOGRAPHY: Gordon McCallum entered the British film industry in 1935 as a loading boy for Herbert Wilcox at British and Dominions. He soon moved into the sound department and worked as a boom swinger on many films of the late 1930s at Denham, Pinewood and Elstree. During the Second World War he worked with both Michael Powell and David Lean on some of their most celebrated films. Between 1945 and 1984 as a resident sound mixer at Pinewood Studios, he made a contribution to over 300 films, including the majority of the output of the Rank Organisation, as well as later major international productions such as The Day of the Jackal (1973), Superman (1978), Blade Runner (1982) and the James Bond series. In 1972 he won an Oscar for his work on Fiddler on the Roof (1971). SUMMARY: In this interview McCallum discusses many of the personalities and productions he has encountered during his long career, as well as reflecting on developments in sound technology, and the qualities needed to make a good dubbing mixer. BECTU History Project - Interview No. 58 [Copyright BECTU] Transcription Date: 2002-09-20 Interview Date: 1988-10-11 Interviewer: Alan Lawson Interviewee: Gordon McCallum Tape 1, Side 1 Alan Lawson : Now, Mac...when were you born? Gordon McCallum : May 26th 1919. Alan Lawson : And where was that? Gordon McCallum : In Chicago. Alan Lawson : In Chicago? Gordon McCallum : [Chuckles.] Yes...that has been a surprise to many people! Alan Lawson : Yes! Gordon McCallum : I came back to England with my parents, who are English, when I was about four, and my schooling, therefore, was in England - that's why they came back, largely. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/25/2021 03:14:56AM Via Free Access

6 Women and the war The Great War, most people would have agreed at the time, was a male cre- ation. Politicians, statesmen and kings bred it and soldiers fought and fed it. Thus far, this study has regarded those women within Bloomsbury whose aes- thetic reactions to the conflict provide such a good starting point when examin- ing the war in this context. What of other women, existing independently from that hot-house of creativity, but who felt similarly? Due to their status in soci- ety as a whole, women necessarily operated within a different cultural milieu to that of men – even when sharing an enlightened, liberal background with them, as within Bloomsbury and its circle. But women emerged from a range of back- grounds and contexts – including that of political agitation linked to specific political aims – whose motivation towards protest, when confronted by the specifics of war, became more individualistic in character and less a part of an organised ‘movement’ or liable to be led by the propaganda of the war-state. Many women in the period leading up to the outbreak of the conflict could lay claim to a history of opposition; during the pre-war period one of the prin- cipal focal points of public dissent against the existing political structure had been the women’s suffrage movement. This cause, by the nature of its specific political goals, had also been largely political in organisation, character and aspiration, though precepts of greater equality for women outside the political sphere – once they had achieved the vote – were meshed to hopes for the ulti- mate cultural emancipation of the female sex. -

The Picture Show Annual (1928)

Hid •v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/pictureshowannuaOOamal Corinne Griffith, " The Lady in Ermine," proves a shawl and a fan are just as becoming. Corinne is one of the long-established stars whose popularity shows no signs of declining and beauty no signs of fading. - Picture Show Annual 9 rkey Ktpt~ thcMouies Francis X. Bushman as Messala, the villain of the piece, and Ramon Novarro, the hero, in " Ben Hut." PICTURESQUE PERSONALITIES OF THE PICTURES—PAST AND PRESENT ALTHOUGH the cinema as we know it now—and by that I mean plays made by moving pictures—is only about eighteen years old (for it was in the Wallace spring of 1908 that D. W. Griffith started to direct for Reid, the old Biograph), its short history is packed with whose death romance and tragedy. robbed the screen ofa boyish charm Picture plays there had been before Griffith came on and breezy cheer the scene. The first movie that could really be called iness that have a picture play was " The Soldier's Courtship," made by never been replaced. an Englishman, Robert W. Paul, on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre in 18% ; but it was in the Biograph Studio that the real start was made with the film play. Here Mary Pickford started her screen career, to be followed later by Lillian and Dorothy Gish, and the three Talmadge sisters. Natalie Talmadge did not take as kindly to film acting as did her sisters, and when Norma and Constance had made a name and the family had gone from New York to Hollywood Natalie went into the business side of the films and held some big positions before she retired on her marriage with Buster Keaton.