Copyright 2015 Carola Dwyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y 2 [3 2(111T GLERK Or Ciol1rt 8Uprcivie COURT of OI Ll0 in the SUPREME COURT of OHIO

IN THF, SiIPRF,ME COURT OF OHIO STATE OF OHIO, Case No. 98-20 Appellee, V. RICHARD NIELDS, TIIIS IS A DEATH PENALTY CASE Appellant, NOTICE OF FILING CAROL A. WRTGHT (0029782) Assistant Federal Public Defender Capital Habeas Unit Federal Public Defender's Office Southern District of Ohio 10 W. Broad Street, Ste. 1020 Columbus, Ohio 43215 (614) 469-2999 (614) 469-5999 (Fax) JOSEPH DETERS (0012084) IIamilton County Prosecutor RANDALL L. PORTER (0005835) PHTLI,IP R. CUMMINGS (0041497) Assistant State Public Defender Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Ohio Public Defender's Office 230 E. Ninth Stree, Suite 4000 250 E. Broad Street, Suite 1400 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Columbus, Ohio 43215 (513) 946-3052 (614) 466-5394 (513) 946-3021 (Fax) (614) 644-0708 (Fax) COUNSEL FOR STATE OF OHIO COUNSEL FOR RICHARD NIELDS Y 2 [3 2(111t GLERK or CiOl1RT 8uPRCIViE COURT OF OI ll0 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STATE OF OHIO, Case No. 98-20 Appellee, V. RICHARD NIELDS, THIS IS A DEATH PENALTY CASE Appellant, NOTICE OF FILING Assistant Federal Defender, Carol A. Wright, hereby provides notice that a Stipulated Dismissal Without Prejudice was filed on the 26" day of May, 2010 in U.S. District Court, Case No. 2:04-cv-1156 (Southern District of Ohio, Eastern Division)(attached as Exhibit A). Respectfully submitted, CAROL A. WRIGHT (00297^$) Assistant Federal Public Defe`S'de Capital Habeas Unit Federal Public Defender's Office Southern District of Ohio 10 W. Broad Street, Ste. 1020 Columbus, Ohio 43215 (614) 469-2999 (614) 469-5999 (Fax) Carol Wright(a)fd.= COTJNSL:L FOR RTCHlrTiZD NIELDS CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that a true copy of the foregoing was sent by regular U.S. -

Girl Names Registered in 1996

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaliyah 1 Aiesha 1 Aleeta 1 Aamino 2 Aileen 1 Aleigha 1 Aamna 1 Ailish 2 Aleksandra 1 Aanchal 1 Ailsa 3 Alena 2 Aaryn 4 Aimee 1 Alesha 1 Aashna 1Ainslay 1 Alesia 5 Abbey 1Ainsleigh 1 Alesian 1 Abbi 4Ainsley 6 Alessandra 3 Abbie 1 Airianna 1 Alessia 2 Abbigail 1Airyn 1 Aleta 19 Abby 4 Aisha 5 Alex 1 Abear 1 Aishling 25 Alexa 1 Abena 6 Aislinn 1 Alexander 1 Abigael 1 Aiyana-Marie 128 Alexandra 32 Abigail 2Aja 2 Alexandrea 5 Abigayle 1 Ajdina 29 Alexandria 2 Abir 1 Ajsha 5 Alexia 1 Abrianna 1 Akasha 49 Alexis 1 Abrinna 1Akayla 1 Alexsandra 1 Abyen 2Akaysha 1 Alexus 1 Abygail 1Akelyn 2 Ali 2 Acacia 1 Akosua 7 Alia 1 Accacca 1 Aksana 1 Aliah 1 Ada 1 Akshpreet 1 Alice 1 Adalaine 1 Alabama 38 Alicia 1 Adan 2 Alaina 1 Alicja 1 Adanna 1 Alainah 1 Alicyn 1 Adara 20 Alana 4 Alida 1 Adarah 1 Alanah 2 Aliesha 1 Addisyn 1 Alanda 1 Alifa 1 Adele 1 Alandra 2 Alina 2 Adelle 12 Alanna 1 Aline 1 Adetola 6 Alannah 1 Alinna 1 Adrey 2 Alannis 4 Alisa 1 Adria 1Alara 1 Alisan 9 Adriana 1 Alasha 1 Alisar 6 Adrianna 2 Alaura 23 Alisha 1 Adrianne 1 Alaxandria 2 Alishia 1 Adrien 1 Alayna 1 Alisia 9 Adrienne 1 Alaynna 23 Alison 1 Aerial 1 Alayssia 9 Alissa 1 Aeriel 1 Alberta 1 Alissah 1 Afrika 1 Albertina 1 Alita 4 Aganetha 1 Alea 3 Alix 4 Agatha 2 Aleah 1 Alixandra 2 Agnes 4 Aleasha 4 Aliya 1 Ahmarie 1 Aleashea 1 Aliza 1 Ahnika 7Alecia 1 Allana 2 Aidan 2 Aleena 1 Allannha 1 Aiden 1 Aleeshya 1 Alleah Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 Page 2 of 28 January, 2006 # Baby Girl Names -

The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman*

Cristian, Réka M.. “The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, A Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman.” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 12 (2019) DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2019.359 The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman* Réka M. Cristian Abstract: In this study Cristian surveys the life and work of Baroness Elemérné Bornemissza, née Karola Szilvássy (1876 – 1948), an internationalist Transylvanian aristocrat, primarily known as the famous literary patron of Erdélyi Helikon and lifelong muse of Count Miklós Bánffy de Losoncz, who immortalized her through the character of Adrienne Milóth in his Erdélyi trilógia [‘The Transylvanian Trilogy’]. Research on Karola Szilvássy is still scarce with little known about the life of this maverick woman, who did not comply with the norms of her society. She was an actress and film director during the silent film era, courageous nurse in the World War I, as well as unusual fashion trendsetter, gourmet cookbook writer, Africa traveler—in short, a source of inspiration for many women of her time, and after. Keywords: Karola Szilvássy, Miklós Bánffy, János Kemény, Zoltán Óváry, Transylvanian aristocracy, modern woman, suffrage, polyglot, cosmopolitan, Erdélyi Helikon Biography: Réka M. Cristian is Associate Professor, Chair of the American Studies Department, University of Szeged, and Co-chair of the university’s Inter-American Research Center. She is author of Cultural Vistas and Sites of Identity: Literature, Film and American Studies (2011), co-author (with Zoltán Dragon) of Encounters of the Filmic Kind: Guidebook to Film Theories (2008), and general editor of AMERICANA E-Journal of American Studies in Hungary, as well as its e-book division, AMERICANA eBooks. -

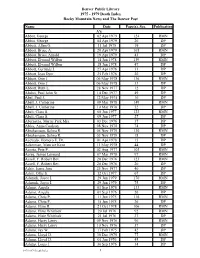

1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post Name Date Page(S), Sec

Denver Public Library 1975 - 1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post Name Date Page(s), Sec. Publication A's Abbot, George 02 Apr 1979 124 RMN Abbot, George 04 Apr 1979 26 DP Abbott, Allen G. 11 Jul 1975 19 DP Abbott, Bruce A. 20 Apr 1979 165 RMN Abbott, Bruce Arnold 19 Apr 1979 43 DP Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 14 Jun 1978 139 RMN Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 18 Jun 1978 47 DP Abbott, Gertrude J. 27 Apr 1976 31 DP Abbott, Jean Dyer 25 Feb 1976 20 DP Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 136 RMN Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 33 DP Abbott, Ruth L. 28 Nov 1977 12 DP Abdoo, Paul John Sr. 14 Dec 1977 49 DP Abel, Paul J. 12 May 1975 16 DP Abell, J. Catherine 09 Mar 1978 149 RMN Abell, J. Catherine 10 Mar 1978 52 DP Abelt, Clara S. 08 Jun 1977 123 RMN Abelt, Clara S. 09 Jun 1977 27 DP Abernatha, Martie Park Mrs. 03 Dec 1976 37 DP Ables, Anna Coulson 08 Nov 1978 74 DP Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 130 RMN Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 18 DP Acevedo, Homero E. Dr. 01 Apr 1978 15 DP Ackerman, Maurice Kent 11 May 1978 44 DP Acosta, Pete P. 02 Aug 1977 103 RMN Acree, Jessee Leonard 07 Mar 1978 97 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 123 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 20 DP Adair, Jense Jane 25 Nov 1977 40 DP Adair, Ollie S. -

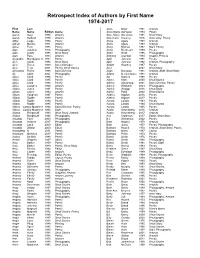

Retrospect Index of Authors by First Name 1974-2017

Retrospect Index of Authors by First Name 1974-2017 First Last Anne Miller 1981 Artwork Name Name Edition Genre Anne Marie DeHaven 1974 Poetry Aaron Gaer 1984 Artwork Anne Marie Sorenson 1991 Short Story Aaron Sullivan 1993 Artwork Annemarie Housley 1976 short story, Poetry Abby Large 1996 Poetry Annie Agars 1988 Artwork Adrian Makins 1991 Artwork Annie Agars 1989 Artwork Ahna Fern 1985 Poetry Annie Morrow 1997 Staff, Poetry Alan Jakubek 1976 Photography Annie Rienheart 1999 Poetry Alan Lundy 1988 Short Story Annie Scott 1996 Photography Alan Pace 1993 Artwork Anthony Arambul 1984 Graphic Printers Alejandro Mandujano Jr. 1997 Poetry April Johnson 1991 Poetry Alex Cantu 1984 Short Story April Johnson 1992 Artwork, Photography Alex Flores 1999 Sales Manager Ardath Guatney 1987 Poetry Alex Trejo 2001 Poetry, Short Stories Ariel 2007 Short Story Alexandra Flores 1998 Sales Director Arjan Buersma 1981 Artwork, Staff, Short Story Ali Alwin 2001 Photography Arlana Beckenhauer 1981 Artwork Alicia Clark 1984 Poetry Art Hansen 1998 Poetry Alicia Clark 1985 Poetry Ashlee Korte 2000 Short Stories Alicia Clark 1986 Poetry Ashley Armstrong 2001 Sales Director, Poetry Alicia Lampley 1994 Artwork Ashley Whitlatch 2003 Photography Alisha Jones 1991 Poetry Ashley Wragge 2016 Short Story Alison Carter 1993 Artwork Ashlyn Paris 2002 Short Stories Alison Vaughan 1997 Poetry Aubrey Higdon 2016 Poetry Allison Radke 1983 Poetry Aubrey Higdon 2017 Poetry Allison Radke 1984 Poetry Aurora Landis 1993 Poetry Allison Radke 1985 Poetry Aurora Landis 1994 Short Stories -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Kielikeskus Tutkii 4/2019 Mike Nelson (Toim.) Kielikeskus Tutkii

Kielikeskus tutkii 4/2019 Mike Nelson (toim.) Kielikeskus tutkii Mike Nelson (toim.) Vol. 4 Turku 2019 Kielikeskus tutkii Vuosikirja nro. 4 Turun yliopisto Kieli- ja viestintäopintojen kielikeskus Agora 20014 Turun yliopisto Sähköposti: [email protected] Vastaava toimittaja: Mike Nelson Kannen kuva: Hanna Oksanen Taitto: Tarja Linden Grano Oy Turku 2019 ISBN 978-951-29-7846-5 (Painettu/PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-7847-2 (PDF) ISSN 2324-0431 (Print) ISSN 2324-044X (PDF) SISÄLTÖ 5 Foreward Student Collaboration in English for Academic Purposes - Theory, Practitioner Perceptions and Reality Averil Bolster & Peter Levrai 9 Tunteet pinnassa Luckan-kahvilan keskusteluryhmässä Carola Karlsson-Fält 27 On a third mission: aligning an entrepreneurial university’s mission, strategy and strategic actions to a language centre context Marise Lehto 43 From analogue to digital: a report on the evolution and delivery of the Finelc 2digi project Mike Nelson 59 What is business English? Key word analysis of the lexis and semantics of business communication Mike Nelson 77 Crossing lines: Finnish and non-Finnish students’ cultural identities and Finnish Nightmares Bridget Palmer 103 Creating a Blended Learning Model for Teaching Academic Presentations Skills to Doctoral Researchers Kelly Raita 115 Tio års perspektiv på förberedande undervisning i svenska som det andra inhemska språket vid Åbo universitet Anne-Maj Åberg 131 Foreward The year 2019 marks the fortieth anniversary of the creation of the University of Turku Language Centre. During this time, the Centre has grown from having two full-time teachers to having fifty-seven in three cities. Looking at the founding documents of the Language Centre in 1979, we see that the main tasks were to teach both domestic and foreign languages, to produce materials for the teaching in cooperation with other language centres, to arrange translation services, to provide teaching for university staff, to provide testing services and to take care of the university’s language studios. -

Death Certificate Index - Webster (7/1919-6/1921 & 1925-1939) Q 7/8/2015

Death Certificate Index - Webster (7/1919-6/1921 & 1925-1939) Q 7/8/2015 Name Birth Date Birth Place Death Date County Mother's Maiden Name Number Box , Elmer 25 Apr. 1921 Iowa 27 May 1921 Webster 94-3571 D2560 Aarons, Anna 30 Apr. 1879 Illinois 31 July 1925 Webster Jordan 094-1008D2562 Abel, Dora 11 Nov. 1891 Iowa 20 Jan. 1930 Webster Zinnerman A094-000D2630 Abel, Emilie A. 02 Sept. 1857 Illinois 30 Dec. 1930 Webster Guenther C94-0260 D2630 Abens, Delmar Dean 06 Feb. 1932 Iowa 19 Apr. 1935 Webster Keck C94-0099D2780 Aberhelman, Wilhelmine 05 Aug. 1858 Germany 25 Oct. 1925 Webster Turhaus 94-0589 D2561 Ablett, Anna Emma 27 Apr. 1871 Kansas 26 Apr. 1925 Webster Erp 94-0528 D2561 Acher, John C. c.1908 Iowa 15 May 1929 Webster Pierson 094-2071 D2563 Acken, Hazel Ester 12 Feb. 1904 Nebraska 24 Sept. 1920 Webster Strouse 94-3299 D2560 Acken, William G. 28 Oct. 1853 Illinois 01 Mar. 1938 Webster McHenry C94-0070 D2883 Ackerman, Curtis Wesley 01 July 1859 New York 18 Feb. 1928 Webster Corey 94-0858 D2563 Ackerman, Ed 13 Apr. 1875 Iowa 19 Apr. 1939 Webster Sibert 94C-0139D2916 Ackerson, Addie Viola 25 Apr. 1865 Iowa 10 Feb. 1926 Webster Parchemer 094-1164 D2562 Ackerson, J.A. 12 Aug. 1866 Wisconsin 28 July 1931 Webster C94-0155D2657 Ackley, Edward Lee 26 July 1936 Iowa 23 Nov. 1936 Webster Schmidt A94-0269 D2814 Ackley, George (Mrs.) 21 Aug. 1882 Missouri 08 Feb. 1936 Webster Bunsh A94-0034D2814 Ackley, Pauline Leone 12 Nov. 1927 Iowa 17 Sept. -

Letter to Court of Appeals Requesting Hearing Re Bar Exam

Hon. Janet DiFiore July 13, 2020 Chief Judge Hon. Michael Garcia Associate Judge The New York Court of Appeals 20 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12207 CC: New York Board of Law Examiners Dear Chief Judge DiFiore and Judge Garcia, We are a coalition of recent law school graduates, practitioners, legal academics, and other interested members of the legal community who write to respectfully request a hearing before the Court to discuss its planned administration of the September bar exam. Recent developments suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic will pose a serious threat to the health of examinees, exam proctors, and the general public in September. The time is ripe for a collaborative discussion of reasonable alternatives to in-person examination. We ask that the Court act swiftly to grant our request for a hearing. As the Court knows, COVID-19 has caused an unprecedented public health crisis, leaving no individual or institution unaffected. The State of New York has suffered greatly, and the need for newly licensed attorneys in our communities has only been compounded by the outbreak. In addition to the general suffering that COVID-19 has wreaked—illness, death, and overwhelming mental stress—law graduates face downstream consequences of the virus, including an economic downturn, high unemployment rates, lack of childcare, and uncertain living situations and access to health insurance.1 COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted Black and Latinx communities in New York2 and throughout the country.3 Further, a national movement for Black lives has led many examinees to devote time and energy to racial justice advocacy. -

Town of Westerly Complete Probate Estate Listing

Town of Westerly Complete Probate Estate Listing Name of Estate Estate Petition For Date Opened Date Closed AALUND, THOMAS 16-117 Will/waived 09-27-2016 ABATE, FRANK 04-26A Voluntary Informal Executor 03-02-2004 03-17-2004 ABATE JR., JOSEPH T. 16-63A Voluntary Informal Administration 05-12-2016 05-18-2016 ABATE, SANDRA LEE 09-147C Name Change 12-02-2009 01-06-2010 ABBRUZZESE, CHARLES N. 09-145 Will/waived 11-30-2009 08-04-2010 ABERLE, EVELYN M. 08-63 Will/waived 05-15-2008 ABOSSO, ANTOINETTE C. 02-116 Will/adv 10-10-2002 08-06-2003 ABOSSO, DOMENIC J. 98-46 Will/waived 05-06-1998 03-17-1999 ABOSSO, DORIS M. 19-160A Voluntary Informal Executor 11-19-2019 12-04-2019 ABRUZZESE, ANTHONY C. 05-44A Will W/o Probate 04-25-2005 04-27-2005 ABRUZZESE, CHARLES H. 98-18 Will/waived 02-12-1998 05-19-2004 ABRUZZESE, MARY M. 21-26A Voluntary Informal Executor 02-12-2021 03-03-2021 ABRUZZESE, RALPH P. 18-63A Will W/o Probate 05-23-2018 05-23-2018 ACHILLES, HENRY LA 96-89 Will/adv 10-15-1996 06-17-1998 ACHILLES, VIRGINIA G. 04-163 Will/waived 12-28-2004 ACKERMAN, GRACE A. 99-05A Voluntary Informal Administration 02-26-1999 03-10-1999 ADAMO, PAT J. 09-86 Will/waived 07-20-2009 05-19-2010 ADAMO, VIOLET 05-33 Will/adv 04-07-2005 03-15-2006 ADAMS, ERIKAH LYN 20-29G Minor Guardianship 02-18-2020 ADAMS, FRANCES C. -

Community Contact Information for Public Water Systems

County Public Water Supply Name PWS ID System Type Total Population Contact Information Mr. William D. Simcoe C‐Community ALBANY ALBANY CITY NY0100189 101082 10 North Enterprise Dr. water system ALBANY, NY 12204 Mr. Jospeh Coffey C‐Community ALBANY ALBANY CITY NY0100189 101082 10 North Enterprise Dr. water system ALBANY, NY 12204 Mr. Jeffrey G Moller C‐Community KOUNTRY KNOLLS ALBANY ALTAMONT VILLAGE NY0100190 2000 water system PO BOX 278 ALTAMONT, NY 12009 Mr. Richard Sayward C‐Community TOWN OF BETHLEHEM WATER DIST. #1 ALBANY BETHLEHEM WD NO 1 NY0100191 31000 water system 143 New Salem So. Road VOORHEESVILLE, NY 12186 Mr. George Kanas C‐Community ALBANY BETHLEHEM WD NO 1 NY0100191 31000 445 Delaware Avenue water system DELMAR, NY 12054 Mr. Darrell Duncan C‐Community HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT ALBANY CLARKSVILLE WATER DISTRICT NY0130000 430 water system 2869 NEW SCOTLAND ROAD VOORHEESVILLE, NY 12186 Mr. John Mcdonald C‐Community COHOES, CITY OF ALBANY COHOES CITY NY0100192 15550 water system 97 MOHAWK STREET COHOES, NY 12047 Frank Leak C‐Community VILLAGE HALL ALBANY COLONIE VILLAGE NY0100194 8030 water system 2 THUNDER RD COLONIE, NY 12205 Mr. Darrell Duncan C‐Community HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT ALBANY FEURA BUSH WD NY0121203 450 water system 2869 NEW SCOTLAND ROAD VOORHEESVILLE, NY 12186 Mr. Jude Watkins C‐Community Pastures of Albany. LLC ALBANY FLEMINGS MOBILE HOME PARK NY0101603 200 water system 225 State St. SCHENECTADY, NY 12305 Mr. Darrell Duncan C‐Community HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT ALBANY FONT GROVE WATER DISTRICT NY0123019 45 water system 2869 NEW SCOTLAND ROAD VOORHEESVILLE, NY 12186 Mr. Raymond M Flowers C‐Community GREEN ACRES ALBANY GREEN ACRES MHP NY0101544 55 water system 223 Curry Bush Rd SCHENECTADY, NY 12306 Ms. -

Higherground

HIGHERGROUND 2006 -2007 Annual Report HIGHERGROUND From the Chairman This year, an exciting and welcome storm broke over our heads: showers of recognition, flashes and rumbles of acceptance, and a flood of global demand for our help in taking solutions to scale. RMI spent the year racing for higher ground—expanding our capabilities and effectiveness to step up to what the world now requires of us. Our steadfast vision of a secure, just, prosperous, and life-sustaining world (“Imagine a world…”) strikes an ever-deeper chord with diverse people and organizations everywhere. RMI’s roadmap for this half-century of change is continuing to unfold in a series of gratifying shifts now snapping into focus. For example, to much industry mirth in 1991, I suggested that a four-seat carbon-fiber car could weigh just 400 kg and get over 100 mpg. This October, Toyota showed such a car; the world’s top maker of carbon fiber announced a factory to mass-produce ultralight auto parts; and our Fiberforge spinoff’s new manufacturing process entered production at an aerospace plant. This summer, two trans- formational RMI car projects with the auto industry exceeded expectations. With leadership from Boeing in airplanes, Wal-Mart in heavy trucks, and the Pentagon in military energy efficiency, RMI’s 2004 Winning the Oil Endgame journey off oil is underway, and we’re focused intently on driving it faster, especially in automaking. In 1976, I foresaw a dramatic market shift toward the decentralized production of electricity. Today, a sixth of the world’s electricity (slightly more than comes from nuclear energy) and a third of the world’s new electricity is so produced.