Kielikeskus Tutkii 4/2019 Mike Nelson (Toim.) Kielikeskus Tutkii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y 2 [3 2(111T GLERK Or Ciol1rt 8Uprcivie COURT of OI Ll0 in the SUPREME COURT of OHIO

IN THF, SiIPRF,ME COURT OF OHIO STATE OF OHIO, Case No. 98-20 Appellee, V. RICHARD NIELDS, TIIIS IS A DEATH PENALTY CASE Appellant, NOTICE OF FILING CAROL A. WRTGHT (0029782) Assistant Federal Public Defender Capital Habeas Unit Federal Public Defender's Office Southern District of Ohio 10 W. Broad Street, Ste. 1020 Columbus, Ohio 43215 (614) 469-2999 (614) 469-5999 (Fax) JOSEPH DETERS (0012084) IIamilton County Prosecutor RANDALL L. PORTER (0005835) PHTLI,IP R. CUMMINGS (0041497) Assistant State Public Defender Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Ohio Public Defender's Office 230 E. Ninth Stree, Suite 4000 250 E. Broad Street, Suite 1400 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Columbus, Ohio 43215 (513) 946-3052 (614) 466-5394 (513) 946-3021 (Fax) (614) 644-0708 (Fax) COUNSEL FOR STATE OF OHIO COUNSEL FOR RICHARD NIELDS Y 2 [3 2(111t GLERK or CiOl1RT 8uPRCIViE COURT OF OI ll0 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STATE OF OHIO, Case No. 98-20 Appellee, V. RICHARD NIELDS, THIS IS A DEATH PENALTY CASE Appellant, NOTICE OF FILING Assistant Federal Defender, Carol A. Wright, hereby provides notice that a Stipulated Dismissal Without Prejudice was filed on the 26" day of May, 2010 in U.S. District Court, Case No. 2:04-cv-1156 (Southern District of Ohio, Eastern Division)(attached as Exhibit A). Respectfully submitted, CAROL A. WRIGHT (00297^$) Assistant Federal Public Defe`S'de Capital Habeas Unit Federal Public Defender's Office Southern District of Ohio 10 W. Broad Street, Ste. 1020 Columbus, Ohio 43215 (614) 469-2999 (614) 469-5999 (Fax) Carol Wright(a)fd.= COTJNSL:L FOR RTCHlrTiZD NIELDS CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify that a true copy of the foregoing was sent by regular U.S. -

Girl Names Registered in 1996

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaliyah 1 Aiesha 1 Aleeta 1 Aamino 2 Aileen 1 Aleigha 1 Aamna 1 Ailish 2 Aleksandra 1 Aanchal 1 Ailsa 3 Alena 2 Aaryn 4 Aimee 1 Alesha 1 Aashna 1Ainslay 1 Alesia 5 Abbey 1Ainsleigh 1 Alesian 1 Abbi 4Ainsley 6 Alessandra 3 Abbie 1 Airianna 1 Alessia 2 Abbigail 1Airyn 1 Aleta 19 Abby 4 Aisha 5 Alex 1 Abear 1 Aishling 25 Alexa 1 Abena 6 Aislinn 1 Alexander 1 Abigael 1 Aiyana-Marie 128 Alexandra 32 Abigail 2Aja 2 Alexandrea 5 Abigayle 1 Ajdina 29 Alexandria 2 Abir 1 Ajsha 5 Alexia 1 Abrianna 1 Akasha 49 Alexis 1 Abrinna 1Akayla 1 Alexsandra 1 Abyen 2Akaysha 1 Alexus 1 Abygail 1Akelyn 2 Ali 2 Acacia 1 Akosua 7 Alia 1 Accacca 1 Aksana 1 Aliah 1 Ada 1 Akshpreet 1 Alice 1 Adalaine 1 Alabama 38 Alicia 1 Adan 2 Alaina 1 Alicja 1 Adanna 1 Alainah 1 Alicyn 1 Adara 20 Alana 4 Alida 1 Adarah 1 Alanah 2 Aliesha 1 Addisyn 1 Alanda 1 Alifa 1 Adele 1 Alandra 2 Alina 2 Adelle 12 Alanna 1 Aline 1 Adetola 6 Alannah 1 Alinna 1 Adrey 2 Alannis 4 Alisa 1 Adria 1Alara 1 Alisan 9 Adriana 1 Alasha 1 Alisar 6 Adrianna 2 Alaura 23 Alisha 1 Adrianne 1 Alaxandria 2 Alishia 1 Adrien 1 Alayna 1 Alisia 9 Adrienne 1 Alaynna 23 Alison 1 Aerial 1 Alayssia 9 Alissa 1 Aeriel 1 Alberta 1 Alissah 1 Afrika 1 Albertina 1 Alita 4 Aganetha 1 Alea 3 Alix 4 Agatha 2 Aleah 1 Alixandra 2 Agnes 4 Aleasha 4 Aliya 1 Ahmarie 1 Aleashea 1 Aliza 1 Ahnika 7Alecia 1 Allana 2 Aidan 2 Aleena 1 Allannha 1 Aiden 1 Aleeshya 1 Alleah Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 Page 2 of 28 January, 2006 # Baby Girl Names -

The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman*

Cristian, Réka M.. “The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, A Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman.” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 12 (2019) DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2019.359 The Life and Times of Karola Szilvássy, Transylvanian Aristocrat and Modern Woman* Réka M. Cristian Abstract: In this study Cristian surveys the life and work of Baroness Elemérné Bornemissza, née Karola Szilvássy (1876 – 1948), an internationalist Transylvanian aristocrat, primarily known as the famous literary patron of Erdélyi Helikon and lifelong muse of Count Miklós Bánffy de Losoncz, who immortalized her through the character of Adrienne Milóth in his Erdélyi trilógia [‘The Transylvanian Trilogy’]. Research on Karola Szilvássy is still scarce with little known about the life of this maverick woman, who did not comply with the norms of her society. She was an actress and film director during the silent film era, courageous nurse in the World War I, as well as unusual fashion trendsetter, gourmet cookbook writer, Africa traveler—in short, a source of inspiration for many women of her time, and after. Keywords: Karola Szilvássy, Miklós Bánffy, János Kemény, Zoltán Óváry, Transylvanian aristocracy, modern woman, suffrage, polyglot, cosmopolitan, Erdélyi Helikon Biography: Réka M. Cristian is Associate Professor, Chair of the American Studies Department, University of Szeged, and Co-chair of the university’s Inter-American Research Center. She is author of Cultural Vistas and Sites of Identity: Literature, Film and American Studies (2011), co-author (with Zoltán Dragon) of Encounters of the Filmic Kind: Guidebook to Film Theories (2008), and general editor of AMERICANA E-Journal of American Studies in Hungary, as well as its e-book division, AMERICANA eBooks. -

Föreningen Luckans Verksamhetsplan 2016

Föreningen Luckan r.f./ Verksamhetsplan 2016 FÖRENINGEN LUCKAN R.F. Reg.nr 181.018 FO-nummer: 1637159-4 VERKSAMHETSPLAN ÅR 2016 3 INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING 1. INLEDNING 4 2. VÄRDERINGAR OCH VISION 5 2.1 Luckans värderingar 5 2.2 Vision 5 3. TYNGDPUNKTSOMRÅDEN 2016 FRAMÅT 6 4. LUCKAN SOM SAMARBETSORGANISATION 9 5. PERSONAL 9 6. EKONOMI OCH PROJEKTFINANSIERING 12 7. ORGANISATION OCH LEDNING 13 8. MARKNADSFÖRING OCH KOMMUNIKATION 14 9. VERKSAMHETER 16 9.1 Centrala målgrupper och nyckeltal 16 9.2 Informationsverksamhet och servicetjänster 19 9.3 Digitala tjänster 20 9.4 Program och kulturverksamhet 24 9.5 Barnkultur för alla barn 25 9.6 Ungdomsrådgivning på svenska – UngInfo 29 9.7 Luckan shop 31 9.8 Luckan Integration 32 10. UTVECKLINGSPROJEKT 36 11. Utvärdering och kvalitetsuppföljning 40 12. Samarbetet med de övriga Luckorna 40 13. Kortbudget Föreningen Luckan r.f. 43 1. INLEDNING Föreningen Luckan r.f. grundades i december år 2000. De grundande föreningarna och samfunden utgörs av fem medlemsorganisationer: Föreningen Konstsamfundet, Samfundet Folkhälsan, Svenska studieförbundet, Sydkustens Landskapsförbund och 4 Understödsföreningen för Svenska Kulturfonden. Syfte och uppdrag Föreningens syfte är att främja svenskspråkig samhällelig och kulturell verksamhet i huvudstadsregionen. Vidare samlar och sprider föreningen information om kulturella och sociala tjänster och aktiviteter, för att på detta sätt öka deras tillgänglighet för en bred allmänhet och grupper med särskilda behov. Föreningen skall främja liknande verksamhet på andra orter i Svenskfi nland. Föreningen fullföljer sitt syfte genom att sammanställa, producera och sprida information, ordna verksamhet i form av rådgivning, utbildningar och sammankomster samt evenemang med inriktning på samhälle och kultur jämte annan motsvarande verksamhet. -

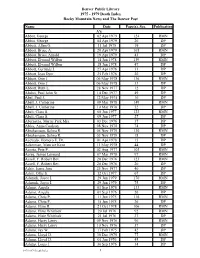

1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post Name Date Page(S), Sec

Denver Public Library 1975 - 1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post Name Date Page(s), Sec. Publication A's Abbot, George 02 Apr 1979 124 RMN Abbot, George 04 Apr 1979 26 DP Abbott, Allen G. 11 Jul 1975 19 DP Abbott, Bruce A. 20 Apr 1979 165 RMN Abbott, Bruce Arnold 19 Apr 1979 43 DP Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 14 Jun 1978 139 RMN Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 18 Jun 1978 47 DP Abbott, Gertrude J. 27 Apr 1976 31 DP Abbott, Jean Dyer 25 Feb 1976 20 DP Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 136 RMN Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 33 DP Abbott, Ruth L. 28 Nov 1977 12 DP Abdoo, Paul John Sr. 14 Dec 1977 49 DP Abel, Paul J. 12 May 1975 16 DP Abell, J. Catherine 09 Mar 1978 149 RMN Abell, J. Catherine 10 Mar 1978 52 DP Abelt, Clara S. 08 Jun 1977 123 RMN Abelt, Clara S. 09 Jun 1977 27 DP Abernatha, Martie Park Mrs. 03 Dec 1976 37 DP Ables, Anna Coulson 08 Nov 1978 74 DP Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 130 RMN Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 18 DP Acevedo, Homero E. Dr. 01 Apr 1978 15 DP Ackerman, Maurice Kent 11 May 1978 44 DP Acosta, Pete P. 02 Aug 1977 103 RMN Acree, Jessee Leonard 07 Mar 1978 97 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 123 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 20 DP Adair, Jense Jane 25 Nov 1977 40 DP Adair, Ollie S. -

Sammanfattning På Svenska Många Av Världens Språk Är S.K

Interaction and Variation in Pluricentric Languages – Communicative Patterns in Sweden Swedish and Finland Swedish FORSKNINGSPROGRAM 2013–2020 RESEARCH PROGRAMME 2013–2020 Finansierat av Riksbankens Jubileumsfond Funded by the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Fund Programbeskrivning från programansökan Programme description from programme application Sammanfattning på svenska Många av världens språk är s.k. pluricentriska språk, dvs. språk som talas i fler länder än ett. Bara i Europa finns en rad exempel på sådana språk, till exempel engelska, franska, tyska och svenska. Men samtalar man på samma sätt i olika länder bara för att man talar samma språk? Eller ser de kommunikativa mönstren olika ut? Det vet vi i dagsläget nästan inget om, och det är just det som programmet Interaktion och variation i pluricentriska språk undersöker. Programmet jämför samma typer av samtal i liknande miljöer i Sverige och Finland, med fokus på domänerna service, lärande och vård där en stor del av samtal utanför den privata sfären utspelar sig. Samtal både mellan personer som känner varandra och sådana som inte gör det kommer att spelas in för att se vilka skillnader det finns i samtalsmönstren mellan sverigesvenska och finlandssvenska samtal. Dessutom upprättas en sökbar databas som också kan användas till framtida undersökningar. En viktig del inom programmet är att bidra till den internationella teoriutvecklingen inom forskningen om pluricentriska språk. Genom att använda teorier och metoder som samtalsanalys och kommunikationsetnografi kan programmet belysa och förklara pluricentriska språkfenomen som tidigare forskning inte riktigt kunnat komma åt. På så vis bidrar programmet till att utveckla den s.k. variationspragmatiken samtidigt som vi får ny kunskap om vad som är unikt för finlandssvenska respektive sverigesvenska samtal. -

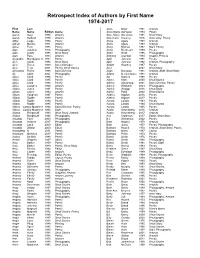

Retrospect Index of Authors by First Name 1974-2017

Retrospect Index of Authors by First Name 1974-2017 First Last Anne Miller 1981 Artwork Name Name Edition Genre Anne Marie DeHaven 1974 Poetry Aaron Gaer 1984 Artwork Anne Marie Sorenson 1991 Short Story Aaron Sullivan 1993 Artwork Annemarie Housley 1976 short story, Poetry Abby Large 1996 Poetry Annie Agars 1988 Artwork Adrian Makins 1991 Artwork Annie Agars 1989 Artwork Ahna Fern 1985 Poetry Annie Morrow 1997 Staff, Poetry Alan Jakubek 1976 Photography Annie Rienheart 1999 Poetry Alan Lundy 1988 Short Story Annie Scott 1996 Photography Alan Pace 1993 Artwork Anthony Arambul 1984 Graphic Printers Alejandro Mandujano Jr. 1997 Poetry April Johnson 1991 Poetry Alex Cantu 1984 Short Story April Johnson 1992 Artwork, Photography Alex Flores 1999 Sales Manager Ardath Guatney 1987 Poetry Alex Trejo 2001 Poetry, Short Stories Ariel 2007 Short Story Alexandra Flores 1998 Sales Director Arjan Buersma 1981 Artwork, Staff, Short Story Ali Alwin 2001 Photography Arlana Beckenhauer 1981 Artwork Alicia Clark 1984 Poetry Art Hansen 1998 Poetry Alicia Clark 1985 Poetry Ashlee Korte 2000 Short Stories Alicia Clark 1986 Poetry Ashley Armstrong 2001 Sales Director, Poetry Alicia Lampley 1994 Artwork Ashley Whitlatch 2003 Photography Alisha Jones 1991 Poetry Ashley Wragge 2016 Short Story Alison Carter 1993 Artwork Ashlyn Paris 2002 Short Stories Alison Vaughan 1997 Poetry Aubrey Higdon 2016 Poetry Allison Radke 1983 Poetry Aubrey Higdon 2017 Poetry Allison Radke 1984 Poetry Aurora Landis 1993 Poetry Allison Radke 1985 Poetry Aurora Landis 1994 Short Stories -

På Svenska I Finland-In Swedish in Finland

PÅ SVENSKA I FINLAND IN SWEDISH IN FINLAND PÅ SVENSKA I FINLAND IN SWEDISH IN FINLAND Denna skrift riktar sig till dig som är nyfiken på det svenska i det finländska samhället. Som du kanske vet är Finland ett land med två nationalspråk, finska och This book is for you who are curious about the Swedish svenska, som båda har samma juridiska status. De som language and culture within the Finnish society. As har svenska som sitt modersmål är mycket färre än de you may know, Finland is a country with two nation- som har finska så det kan vara så att du varken mött al languages, Finnish and Swedish, which both have svenskan på stan eller erbjudits möjligheten att inte- the same legal status. There are very few people with greras på svenska. Swedish as a mother tongue compared to those with Du får bekanta dig med Finland som en del av Finnish, so you may have neither encountered Swedish Norden samt Sveriges och Finlands gemensamma his- language spoken in town, nor been offered the choice toria. I en artikel presenteras kort hur det är att studera to integrate in Swedish. på svenska, i en annan hur det är att jobba och i en You’ll familiarise yourself with Finland as a Nor- tredje hur det är att vara förälder på svenska i Finland. dic country, as well as with Finland’s mutual history En stor del av som intervjuas har själv flyttat till Fin- with Sweden. One of the articles presents studying land. Du får också en inblick hur det var att vara ny in Swedish, while another talks about what it is like i Finland förr i världen och hur de som flyttade från to work in Swedish, and a third one explores what it Ryssland till Finland under slutet av 1800-talet samti- means to be a parent in Swedish in Finland. -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Death Certificate Index - Webster (7/1919-6/1921 & 1925-1939) Q 7/8/2015

Death Certificate Index - Webster (7/1919-6/1921 & 1925-1939) Q 7/8/2015 Name Birth Date Birth Place Death Date County Mother's Maiden Name Number Box , Elmer 25 Apr. 1921 Iowa 27 May 1921 Webster 94-3571 D2560 Aarons, Anna 30 Apr. 1879 Illinois 31 July 1925 Webster Jordan 094-1008D2562 Abel, Dora 11 Nov. 1891 Iowa 20 Jan. 1930 Webster Zinnerman A094-000D2630 Abel, Emilie A. 02 Sept. 1857 Illinois 30 Dec. 1930 Webster Guenther C94-0260 D2630 Abens, Delmar Dean 06 Feb. 1932 Iowa 19 Apr. 1935 Webster Keck C94-0099D2780 Aberhelman, Wilhelmine 05 Aug. 1858 Germany 25 Oct. 1925 Webster Turhaus 94-0589 D2561 Ablett, Anna Emma 27 Apr. 1871 Kansas 26 Apr. 1925 Webster Erp 94-0528 D2561 Acher, John C. c.1908 Iowa 15 May 1929 Webster Pierson 094-2071 D2563 Acken, Hazel Ester 12 Feb. 1904 Nebraska 24 Sept. 1920 Webster Strouse 94-3299 D2560 Acken, William G. 28 Oct. 1853 Illinois 01 Mar. 1938 Webster McHenry C94-0070 D2883 Ackerman, Curtis Wesley 01 July 1859 New York 18 Feb. 1928 Webster Corey 94-0858 D2563 Ackerman, Ed 13 Apr. 1875 Iowa 19 Apr. 1939 Webster Sibert 94C-0139D2916 Ackerson, Addie Viola 25 Apr. 1865 Iowa 10 Feb. 1926 Webster Parchemer 094-1164 D2562 Ackerson, J.A. 12 Aug. 1866 Wisconsin 28 July 1931 Webster C94-0155D2657 Ackley, Edward Lee 26 July 1936 Iowa 23 Nov. 1936 Webster Schmidt A94-0269 D2814 Ackley, George (Mrs.) 21 Aug. 1882 Missouri 08 Feb. 1936 Webster Bunsh A94-0034D2814 Ackley, Pauline Leone 12 Nov. 1927 Iowa 17 Sept. -

Letter to Court of Appeals Requesting Hearing Re Bar Exam

Hon. Janet DiFiore July 13, 2020 Chief Judge Hon. Michael Garcia Associate Judge The New York Court of Appeals 20 Eagle Street Albany, New York 12207 CC: New York Board of Law Examiners Dear Chief Judge DiFiore and Judge Garcia, We are a coalition of recent law school graduates, practitioners, legal academics, and other interested members of the legal community who write to respectfully request a hearing before the Court to discuss its planned administration of the September bar exam. Recent developments suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic will pose a serious threat to the health of examinees, exam proctors, and the general public in September. The time is ripe for a collaborative discussion of reasonable alternatives to in-person examination. We ask that the Court act swiftly to grant our request for a hearing. As the Court knows, COVID-19 has caused an unprecedented public health crisis, leaving no individual or institution unaffected. The State of New York has suffered greatly, and the need for newly licensed attorneys in our communities has only been compounded by the outbreak. In addition to the general suffering that COVID-19 has wreaked—illness, death, and overwhelming mental stress—law graduates face downstream consequences of the virus, including an economic downturn, high unemployment rates, lack of childcare, and uncertain living situations and access to health insurance.1 COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted Black and Latinx communities in New York2 and throughout the country.3 Further, a national movement for Black lives has led many examinees to devote time and energy to racial justice advocacy. -

Town of Westerly Complete Probate Estate Listing

Town of Westerly Complete Probate Estate Listing Name of Estate Estate Petition For Date Opened Date Closed AALUND, THOMAS 16-117 Will/waived 09-27-2016 ABATE, FRANK 04-26A Voluntary Informal Executor 03-02-2004 03-17-2004 ABATE JR., JOSEPH T. 16-63A Voluntary Informal Administration 05-12-2016 05-18-2016 ABATE, SANDRA LEE 09-147C Name Change 12-02-2009 01-06-2010 ABBRUZZESE, CHARLES N. 09-145 Will/waived 11-30-2009 08-04-2010 ABERLE, EVELYN M. 08-63 Will/waived 05-15-2008 ABOSSO, ANTOINETTE C. 02-116 Will/adv 10-10-2002 08-06-2003 ABOSSO, DOMENIC J. 98-46 Will/waived 05-06-1998 03-17-1999 ABOSSO, DORIS M. 19-160A Voluntary Informal Executor 11-19-2019 12-04-2019 ABRUZZESE, ANTHONY C. 05-44A Will W/o Probate 04-25-2005 04-27-2005 ABRUZZESE, CHARLES H. 98-18 Will/waived 02-12-1998 05-19-2004 ABRUZZESE, MARY M. 21-26A Voluntary Informal Executor 02-12-2021 03-03-2021 ABRUZZESE, RALPH P. 18-63A Will W/o Probate 05-23-2018 05-23-2018 ACHILLES, HENRY LA 96-89 Will/adv 10-15-1996 06-17-1998 ACHILLES, VIRGINIA G. 04-163 Will/waived 12-28-2004 ACKERMAN, GRACE A. 99-05A Voluntary Informal Administration 02-26-1999 03-10-1999 ADAMO, PAT J. 09-86 Will/waived 07-20-2009 05-19-2010 ADAMO, VIOLET 05-33 Will/adv 04-07-2005 03-15-2006 ADAMS, ERIKAH LYN 20-29G Minor Guardianship 02-18-2020 ADAMS, FRANCES C.