Arxiv:1802.01280V2 [Physics.App-Ph] 6 Feb 2018 Sinipatto N Neln Nbl N Nanocrystalli and Bulk in Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P142 Lecture 19

P142 Lecture 19 SUMMARY Vector derivatives: Cartesian Coordinates Vector derivatives: Spherical Coordinates See Appendix A in “Introduction to Electrodynamics” by Griffiths P142 Preview; Subject Matter P142 Lecture 19 • Electric dipole • Dielectric polarization • Electric fields in dielectrics • Electric displacement field, D • Summary Dielectrics: Electric dipole The electric dipole moment p is defined as p = q d where d is the separation distance between the charges q pointing from the negative to positive charge. Lecture 5 showed that Forces on an electric dipole in E field Torque: Forces on an electric dipole in E field Translational force: Dielectric polarization: Microscopic Atomic polarization: d ~ 10-15 m Molecular polarization: d ~ 10-14 m Align polar molecules: d ~ 10-10 m Competition between alignment torque and thermal motion or elastic forces Linear dielectrics: Three mechanisms typically lead to Electrostatic precipitator Linear dielectric: Translational force: Electrostatic precipitator Extract > 99% of ash and dust from gases at power, cement, and ore-processing plants Electric field in dielectrics: Macroscopic Electric field in dielectrics: Macroscopic Polarization density P in dielectrics: Polarization density in dielectrics: Polarization density in dielectrics: The dielectric constant κe • Net field in a dielectric Enet = EExt/κe • Most dielectrics linear up to dielectric strength Volume polarization density Electric Displacement Field Electric Displacement Field Electric Displacement Field Electric Displacement Field Summary; 1 Summary; 2 Refraction of the electric field at boundaries with dielectrics Capacitance with dielectrics Capacitance with dielectrics Electric energy storage • Showed last lecture that the energy stored in a capacitor is given by where for a dielectric • Typically it is more useful to express energy in terms of magnitude of the electric field E. -

Modeling Optical Metamaterials with Strong Spatial Dispersion

Fakultät für Physik Institut für theoretische Festkörperphysik Modeling Optical Metamaterials with Strong Spatial Dispersion M. Sc. Karim Mnasri von der KIT-Fakultät für Physik des Karlsruher Instituts für Technologie (KIT) genehmigte Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (Dr. rer. nat.) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 29. November 2019 Referent: Prof. Dr. Carsten Rockstuhl (Institut für theoretische Festkörperphysik) Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Michael Plum (Institut für Analysis) KIT – Die Forschungsuniversität in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft Erklärung zur Selbstständigkeit Ich versichere, dass ich diese Arbeit selbstständig verfasst habe und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel benutzt habe, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich über- nommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht und die Satzung des KIT zur Sicherung guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis in der gültigen Fassung vom 24. Mai 2018 beachtet habe. Karlsruhe, den 21. Oktober 2019, Karim Mnasri Als Prüfungsexemplar genehmigt von Karlsruhe, den 28. Oktober 2019, Prof. Dr. Carsten Rockstuhl iv To Ouiem and Adam Thesis abstract Optical metamaterials are artificial media made from subwavelength inclusions with un- conventional properties at optical frequencies. While a response to the magnetic field of light in natural material is absent, metamaterials prompt to lift this limitation and to exhibit a response to both electric and magnetic fields at optical frequencies. Due tothe interplay of both the actual shape of the inclusions and the material from which they are made, but also from the specific details of their arrangement, the response canbe driven to one or multiple resonances within a desired frequency band. With such a high number of degrees of freedom, tedious trial-and-error simulations and costly experimen- tal essays are inefficient when considering optical metamaterials in the design of specific applications. -

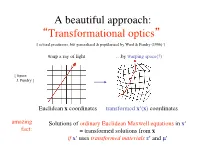

A Beautiful Approach: Transformational Optics

A beautiful approach: “Transformational optics” [ several precursors, but generalized & popularized by Ward & Pendry (1996) ] warp a ray of light …by warping space(?) [ figure: J. Pendry ] Euclidean x coordinates transformed x'(x) coordinates amazing Solutions of ordinary Euclidean Maxwell equations in x' fact: = transformed solutions from x if x' uses transformed materials ε' and μ' Maxwell’s Equations constants: ε0, μ0 = vacuum permittivity/permeability = 1 –1/2 c = vacuum speed of light = (ε0 μ0 ) = 1 ! " B = 0 Gauss: constitutive ! " D = # relations: James Clerk Maxwell #D E = D – P 1864 Ampere: ! " H = + J #t H = B – M $B Faraday: ! " E = # $t electromagnetic fields: sources: J = current density E = electric field ρ = charge density D = displacement field H = magnetic field / induction material response to fields: B = magnetic field / flux density P = polarization density M = magnetization density Constitutive relations for macroscopic linear materials P = χe E ⇒ D = (1+χe) E = ε E M = χm H B = (1+χm) H = μ H where ε = 1+χe = electric permittivity or dielectric constant µ = 1+χm = magnetic permeability εµ = (refractive index)2 Transformation-mimicking materials [ Ward & Pendry (1996) ] E(x), H(x) J–TE(x(x')), J–TH(x(x')) [ figure: J. Pendry ] Euclidean x coordinates transformed x'(x) coordinates J"JT JµJT ε(x), μ(x) " ! = , µ ! = (linear materials) det J det J J = Jacobian (Jij = ∂xi’/∂xj) (isotropic, nonmagnetic [μ=1], homogeneous materials ⇒ anisotropic, magnetic, inhomogeneous materials) an elementary derivation [ Kottke (2008) ] consider× -

![Arxiv:1905.08341V1 [Physics.App-Ph] 20 May 2019 by Discussing the Influence of the Presented Method in Not Yet Conducted for Cylindrical Metasurfaces](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5605/arxiv-1905-08341v1-physics-app-ph-20-may-2019-by-discussing-the-in-uence-of-the-presented-method-in-not-yet-conducted-for-cylindrical-metasurfaces-1045605.webp)

Arxiv:1905.08341V1 [Physics.App-Ph] 20 May 2019 by Discussing the Influence of the Presented Method in Not Yet Conducted for Cylindrical Metasurfaces

Illusion Mechanisms with Cylindrical Metasurfaces: A General Synthesis Approach Mahdi Safari1, Hamidreza Kazemi2, Ali Abdolali3, Mohammad Albooyeh2;∗, and Filippo Capolino2 1Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 2Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of California, Irvine, CA 92617, USA 3Department of Electrical Engineering, Iran University of Science and Technology, Narmak, Tehran, Iran corresponding author: ∗[email protected] We explore the use of cylindrical metasurfaces in providing several illusion mechanisms including scattering cancellation and creating fictitious line sources. We present the general synthesis approach that leads to such phenomena by modeling the metasurface with effective polarizability tensors and by applying boundary conditions to connect the tangential components of the desired fields to the required surface polarization current densities that generate such fields. We then use these required surface polarizations to obtain the effective polarizabilities for the synthesis of the metasurface. We demonstrate the use of this general method for the synthesis of metasurfaces that lead to scattering cancellation and illusion effects, and discuss practical scenarios by using loaded dipole antennas to realize the discretized polarization current densities. This study is the first fundamental step that may lead to interesting electromagnetic applications, like stealth technology, antenna synthesis, wireless power transfer, sensors, cylindrical absorbers, etc. I. INTRODUCTION formal metaurfaces with large radial curvatures (at the wavelength scale) [41]. However, that method was based on the analysis of planar structures with open bound- Metasurfaces are surface equivalents of bulk meta- aries while a cylindrical metasurface can be generally materials, usually realized as dense planar arrays of closed in its azimuthal plane and it involves rather differ- subwavelength-sized resonant particles [1{4]. -

Dielectric Cylinder That Rotates in a Uniform Magnetic Field Kirk T

Dielectric Cylinder That Rotates in a Uniform Magnetic Field Kirk T. McDonald Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 (Mar. 12, 2003) 1Problem A cylinder of relative dielectric constant εr rotates with constant angular velocity ω about its axis. A uniform magnetic field B is parallel to the axis, in the same sense as ω.Find the resulting dielectric polarization P in the cylinder and the surface and volume charge densities σ and ρ, neglecting terms of order (ωa/c)2,wherea is the radius of the cylinder. This problem can be conveniently analyzed by starting in the rotating frame, in which P = P and E = E+v×B,when(v/c)2 corrections are neglected. Consider also the electric displacement D. 2Solution The v × B force on an atom in the rotating cylinder is radially outwards, and increas- ing linearly with radius, so we expect a positive radial polarization P = Pˆr in cylindrical coordinates. There will be an electric field E inside the dielectric associated with this polarization. We now have a “chicken-and-egg” problem: the magnetic field induces some polarization in the rotating cylinder, which induces some electric field, which induces some more polarization, etc. One way to proceed is to follow this line of thought to develop an iterative solution for the polarization. This is done somewhat later in the solution. Or, we can avoid the iterative approach by going to the rotating frame, where there is no interaction between the medium and the magnetic field, but where there is an effective electric field E. -

Maxwellian Vacuum Polarization Kirk T

Maxwellian Vacuum Polarization Kirk T. McDonald Joseph Henry Laboratories, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544 (June 2, 2012) 1Problem Maxwell formulated his dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field [1] without a crisp vision of the nature of electric charge. The notion that electric charge resides on (rather than, say, in the space/æther outside) “point” particles became widely accepted only after the great 1892 monograph of Lorentz [2]. Nonetheless, Maxwell’s equations are consistent with the view that “free” charges and currents do not exist, and that all charges and cur- rents are related to “bound” electric and magnetic polarization densities P and M in the æther/vacuum according to ∂ ρ −∇ · , P c∇ × , total = P Jtotal = ∂t + M (1) in Gaussian units, where ρtotal and Jtotal are the densities of (bound = total) electric charge and current, respectively. Discuss the bound polarizations associated with a “point” electric charge q, and “point” electric and magnetic dipoles p and m, which may be in motion. 2Solution In the convention of eq. (1), Maxwell’s equations can be written as ∇ · E =4πρtotal = −4π∇ · P, (2) ∇ · B =0, (3) ∂ ∇ × −1 B , E = c ∂t (4) π ∂ ∂ π ∇ × 4 Jtotal 1 E π∇ × 1 (E +4 P) , B = c + c ∂t =4 M + c ∂t (5) If we make the usual definitions of the auxiliary fields, D = E +4πP, H = B − 4πM, (6) then ∂ ∇ · , ∇ × 1 D , D =0 H = c ∂t (7) as expected since there are no “free” charges or currents by definition. If ρtotal and Jtotal are known then the equations (2)-(5) have formal solutions for E and B, since both the curl and divergences of these fields are specified. -

Quantum Mechanics Polarization Density

Quantum Mechanics_polarization density In classical electromagnetism, polarization density (or electric polarization, or simplypolarization) is the vector field that expresses the density of permanent or induced electric dipole moments in a dielectric material. When a dielectric is placed in an external Electric field, its molecules gain Electric dipole moment and the dielectric is said to be polarized. The electric dipole moment induced per unit volume of the dielectric material is called the electric polarization of the dielectric.[1][2] Polarization density also describes how a material responds to an applied electric field as well as the way the material changes the electric field, and can be used to calculate the forces that result from those interactions. It can be compared to Magnetization, which is the measure of the corresponding response of a material to a Magnetic field in Magnetism. TheSI unit of measure is coulombs per square metre, and polarization density is represented by a vectorP.[3] Definition The polarization density P is defined as the average Electric dipole moment d per unit volume V of the dielectric material:[4] which can be interpreted as a measure of how strong and how aligned the dipoles are in a region of the material. For the calculation of P due to an applied electric field, the electric susceptibility χ of the dielectric must be known (see below). Polarization density in Maxwell's equations The behavior of electric fields (E and D), magnetic fields (B, H), charge density (ρ) and current density (J) are described by Maxwell's equations in matter. The role of the polarization density P is described below. -

Quantum Mechanics Electric Dipole Moment

Quantum Mechanics_electric dipole moment In physics, the electric dipole moment is a measure of the separation of positive and negative electrical charges in a system of electric charges, that is, a measure of the charge system's overall polarity. The SI units are Coulomb-meter (C m). This article is limited to static phenomena, and does not describe time-dependent or dynamic polarization. Elementary definition Animation showing the Electric field of an electric dipole. The dipole consists of two point electric charges of opposite polarity located close together. A transformation from a point-shaped dipole to a finite-size electric dipole is shown. A molecule of water is polar because of the unequal sharing of its electrons in a "bent" structure. A separation of charge is present with negative charge in the middle (red shade), and positive charge at the ends (blue shade). In the simple case of two point charges, one with charge +q and the other one with charge −q, the electric dipole moment p is: where d is the displacement vector pointing from the negative charge to the positive charge. Thus, the electric dipole moment vector p points from the negative charge to the positive charge. An idealization of this two-charge system is the electrical point dipole consisting of two (infinite) charges only infinitesimally separated, but with a finite p. Torque Electric dipole p and its torque τin a uniform E field. An object with an electric dipole moment is subject to a torque τ when placed in an external electric field. The torque tends to align the dipole with the field, and makes alignment an orientation of lower potential energy than misalignment. -

Time-Modulated Metasurfaces

Posted: June 20, 2021 Pseudo-Random Sequence (PRS) (Space)Time-Modulated Metasurfaces Xiaoyi Wang1,* and Christophe Caloz2 1Department of electrical engineering, Polytechnique Montréal, Montréal, Canada 2Department of electrical engineering, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a novel class of (space)time-modulated metasurfaces, namely (space)time meta- surfaces that are modulated by pseudo-random sequence (PRS) waveforms. In contrast to their harmon- ically or quasi-harmonically modulated counterparts, these metasurfaces massively alter the temporal spectrum of the waves that they process; as a result, they exhibit distinct properties and offer com- plementary applications. These metasurfaces are assumed here to operate in the ‘slow-modulation’ regime, where the fixed-state time between state-transition is much larger than the transient time asso- ciated with the dispersion of the media involved, which allows safe separation of the time-variance and frequency-dispersive effects of the system. Thanks to the special properties of their modulation, which are generally assumed to have a staircase shape and to be periodic in addition to being pseudo-random, the PRS (space)time-modulated metasurfaces can perform a number of unique operations, such as spec- trum spreading, interference suppression, and row/cell selection. These properties, combined with mod- ern microwave CMOS technologies, lead to applications with unique performance or/and features, such as electromagnetic stealth, secured communication, direction of arrival estimation, and spatial multi- plexing. 1 Introduction After hardly a decade of intensive worldwide research, metasurfaces have become a revolutionary advance in microwave, terahertz and optical technologies (1), and this area is far from being exhausted at the time of this writing. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 9 MAGNETIZATION 9.0 INTRODUCTION The sources of the magnetic fields considered in Chap. 8 were conduction currents associated with the motion of unpaired charge carriers through materials. Typically, the current was in a metal and the carriers were conduction electrons. In this chapter, we recognize that materials provide still other magnetic field sources. These account for the fields of permanent magnets and for the increase in inductance produced in a coil by insertion of a magnetizable material. Magnetization effects are due to the propensity of the atomic constituents of matter to behave as magnetic dipoles. It is natural to think of electrons circulating around a nucleus as comprising a circulating current, and hence giving rise to a magnetic moment similar to that for a current loop, as discussed in Example 8.3.2. More surprising is the magnetic dipole moment found for individual electrons. This moment, associated with the electronic property of spin, is defined as the Bohr magneton e 1 m = ± ¯h (1) e m 2 11 where e/m is the electronic chargetomass ratio, 1.76 × 10 coulomb/kg, and 2π¯h −34 2 is Planck’s constant, ¯h = 1.05 × 10 joulesec so that me has the units A − m . -

Maxwell's Equations

Department of Engineering Lecture 15: Maxwell’s Equations Matthew Spencer Harvey Mudd College E157 – Radio Frequency Circuit Design 1 1 Department of Engineering Review of Maxwell’s Equations Matthew Spencer Harvey Mudd College E157 – Radio Frequency Circuit Design 2 In this video we’re going to discuss Maxwell’s Equations. 2 Department of Engineering E and B Describe Forces on Charges 퐹 =푞(퐸+푣×퐵) The Lorentz Force 3 Maxwell’s Equations describe how electric and magnetic fields behave, so understanding Maxwell will require revisiting electric and magnetic fields. The simplest way to understand fields is to think of them as a shorthand for how charges move around. That understanding is summarized in the Lorentz force equation pictured on this slide. The equation says that a particle with charge q will experience a force in the direction of an electric field and perpendicular to a magnetic field if the charge is moving. SKIP As a side-note for the physics-minded, this definition of E and B fields isn’t is not super-widely used because you can’t actually make a point charge to measure E and B if they’re defined this way. Even so, I think it gives good understanding of what E and B do, so we’re keeping it. 3 Department of Engineering Units: E=[V/m], H=[A/m], H is B in a Material 퐷=휖퐸 +푃 Electric Displacement Field [C/m^2] Polarization Density (macroscopic dipole moment) [C/m^2] Electric Field [V/m] 푉=− 퐸⋅푑푙 Permittivity [F/m] (8.85 pF/m in free space) 퐵 = 휇 (퐻+푀) Magnetic flux density [T] Magnetization [A/m] Magnetic field strength [A/m] Permeability [H/m] (4π/10 µH/m in free space) 퐼 = 퐻⋅푑푙 4 We need to talk about the units of E field and eventually B field to cement our understanding of them. -

Maxwell's Macroscopic Equations, the Lorentz Law

Maxwell’s macroscopic equations, the energy-momentum postulates, and the Lorentz law of force † ‡ Masud Mansuripur and Armis R. Zakharian † College of Optical Sciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 ‡ Corning Incorporated, Science and Technology Division, Corning, New York 14831 [Published in Physical Review E 79, 026608, pp 1-10 (2009).] Abstract. We argue that the classical theory of electromagnetism is based on Maxwell’s macroscopic equations, an energy postulate, a momentum postulate, and a generalized form of the Lorentz law of force. These seven postulates constitute the foundation of a complete and consistent theory, thus eliminating the need for actual (i.e., physical) models of polarization P and magnetization M, these being the distinguishing features of Maxwell’s macroscopic equations. In the proposed formulation, P(r, t) and M(r, t) are arbitrary functions of space and time, their physical properties being embedded in the seven postulates of the theory. The postulates are self-consistent, comply with the requirements of the special theory of relativity, and satisfy the laws of conservation of energy, linear momentum, and angular momentum. One advantage of the proposed formulation is that it side-steps the long-standing Abraham-Minkowski controversy surrounding the electromagnetic momentum inside a material medium by simply “assigning” the Abraham momentum density E(r, t)×H(r, t)/c2 to the electromagnetic field. This well-defined momentum is thus taken to be universal as it does not depend on whether the field is propagating or evanescent, and whether or not the host medium is homogeneous, transparent, isotropic, dispersive, magnetic, linear, etc.