Opening a Stock Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Relationship Between Risk and Expected Return in the BRVM Stock Exchange: Test of the CAPM

www.sciedu.ca/rwe Research in World Economy Vol. 5, No. 1; 2014 An Analysis of the Relationship between Risk and Expected Return in the BRVM Stock Exchange: Test of the CAPM Kolani Pamane1 & Anani Ekoue Vikpossi2 1 School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China 2 Swakop Uranium (Propriety) Ltd, Olympia Windhoek, Namibia Correspondence: Kolani Pamane, School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 22, 2010 Accepted: November 10, 2010 Online Published: March 1, 2014 doi:10.5430/rwe.v5n1p13 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v5n1p13 Abstract One of the most important concepts in investment theory is the relationship between risk and return. This relationship drives the theoretical foundation of many investment models such as the well known Capital Asset Pricing Model which predicts that the expected return on an asset above the risk-free rate is linearly related to the non-diversifiable risk measured by its beta. This study examines the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and test it validity for the WAEMU space stock market called BRVM (BOURSE REGIONALE DES VALEURS MOBILIERES) using monthly stock returns from 17 companies listed on the stock exchange for the period of January 2000 to December 2008. Combining Black, Jensen and Scholes with Fama and Macbeth methods of testing the CAPM, the whole period was divided into four sub-periods and stock’s betas used instead of portfolio’s betas due to the small size of the sample. The CAPM’s prediction for the intercept is that it should equal zero and the slope should equal the excess returns on the market portfolio. -

Msci Index Calculation Methodology

INDEX METHODOLOGY MSCI INDEX CALCULATION METHODOLOGY Index Calculation Methodology for the MSCI Equity Indexes Esquivel, Carlos July 2018 JULY 2018 MSCI INDEX CALCULATION METHODOLOGY | JULY 2018 CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................................................... 4 MSCI Equity Indexes........................................................................... 5 1 MSCI Price Index Methodology ................................................... 6 1.1 Price Index Level ....................................................................................... 6 1.2 Price Index Level (Alternative Calculation Formula – Contribution Method) ............................................................................................................ 10 1.3 Next Day Initial Security Weight ............................................................ 15 1.4 Closing Index Market Capitalization Today USD (Unadjusted Market Cap Today USD) ........................................................................................................ 16 1.5 Security Index Of Price In Local .............................................................. 17 1.6 Note on Index Calculation In Local Currency ......................................... 19 1.7 Conversion of Indexes Into Another Currency ....................................... 19 2 MSCI Daily Total Return (DTR) Index Methodology ................... 21 2.1 Calculation Methodology ....................................................................... 21 2.2 Reinvestment -

Cooperation Among the Stock Exchanges of the Oic Member Countries

Journal of Economic Cooperation, 27 -3 (2006), 121-162 COOPERATION AMONG THE STOCK EXCHANGES OF THE OIC MEMBER COUNTRIES SESRTCIC In response to the increased competition prevailing in the international financial markets, national stock exchanges around the world recently made several attempts to upgrade their cooperation and improve their integration. Those attempts took often the form of coalitions, common trading platforms, mergers, associations, federations and unions. Like others, the OIC countries have recently intensified their efforts to promote cooperation among their stock exchanges with a view to developing and consolidating a mechanism for a possible form of integration among themselves. This paper reviews the experiences of various stock exchange alliances established at regional and international levels and draws some lessons for the OIC countries’ stock exchanges in terms of the need for harmonising their physical, institutional and legal frameworks and policies and sharing their investor base. 1. INTRODUCTION As the international trade and financial flows accelerated, the global economy witnessed an increase in the pace of integration. This process of globalisation is most evidently observed in the capital and financial markets. One important element that has led to such a result is the technological advancement in the information and telecommunications sector. Hence, financial transactions became instantaneous and the information guiding investments open to everybody. In this context, technological advancements and the resulting accelerated flow of information have increased efficiency, fairness, transparency and safety in the international financial and capital markets. 122 Journal of Economic Cooperation As those developments introduced new prospects and benefits to the stock markets all around the world, they increased competition among the financial markets, securities exchanges in particular. -

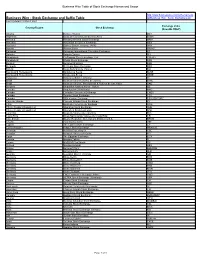

Stock Exchange and Suffix Table Ml/Business Wire Stock Exchanges.Pdf Last Updated 12 March 2021

Business Wire Table of Stock Exchange Names and Usage http://www.businesswire.com/schema/news Business Wire - Stock Exchange and Suffix Table ml/Business_Wire_Stock_Exchanges.pdf Last Updated 12 March 2021 Exchange Value Country/Region Stock Exchange (NewsML ONLY) Albania Bursa e Tiranës BET Argentina Bolsa de Comercio de Buenos Aires BCBA Armenia Nasdaq Armenia Stock Exchange ARM Australia Australian Securities Exchange ASX Australia Sydney Stock Exchange (APX) APX Austria Wiener Börse WBAG Bahamas Bahamas International Securities Exchange BS Bahrain Bahrain Bourse BH Bangladesh Chittagong Stock Exchange, Ltd. CSEBD Bangladesh Dhaka Stock Exchange DSE Belgium Euronext Brussels BSE Bermuda Bermuda Stock Exchange BSX Bolivia Bolsa Boliviana de Valores BO Bosnia and Herzegovina Banjalucka Berza BLSE Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevska Berza SASE Botswana Botswana Stock Exchange BT Brazil Bolsa de Valores do Rio de Janeiro BVRJ Brazil Bolsa de Valores, Mercadorias & Futuros de Sao Paulo SAO Bulgaria Balgarska fondova borsa - Sofiya BB Canada Aequitas NEO Exchange NEO Canada Canadian Securities Exchange CNSX Canada Toronto Stock Exchange TSX Canada TSX Venture Exchange TSX VENTURE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands Stock Exchange KY Chile Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago SGO China, People's Republic of Shanghai Stock Exchange SHH China, People's Republic of Shenzhen Stock Exchange SHZ Colombia Bolsa de Valores de Colombia BVC Costa Rica Bolsa Nacional de Valores de Costa Rica CR Cote d'Ivoire Bourse Regionale Des Valeurs Mobilieres S.A. BRVM Croatia -

Northern Trust Emea Order Execution Policy

NORTHERN TRUST EMEA ORDER EXECUTION POLICY For Professional Clients of the following Northern Trust entities: • Northern Trust Global Services SE, and its branches • Northern Trust Securities LLP, and its branches • The Northern Trust Company, London branch Publication date: 1 January 2021 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Purpose of this policy .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 B. What is Best Execution? ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 POLICY SCOPE ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 A. Northern Trust entities subject to this Policy ................................................................................................................................................. 4 B. Types of Clients ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 C. Activities ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Brvm Stock Market 2015 Year in Review

BRVM Stock Market 1 February 2015 BRVM STOCK MARKET 2015 YEAR IN REVIEW Cheikh Yakhoub Niang, CFA Tel: (+221) 33-869-3140 [email protected] BRVM, the African Leader in 2015 In a year full of difficulties and general disappointment, the West African stock market posted the best yearly performance of the continent at 17.7%. Over 2014 and 2015, the regional market two main indices, the BRVM 10 and the BRVM Composite, experienced cumulative increases of respectively 59% and 83%. Performing as well as the Côte d’Ivoire economy, all but one sector of the BRVM market displayed positive performances during 2015. Overall, it was a good year for the BRVM investors that enjoyed a significantly higher trading volume, with a far greater contribution of smaller cap stocks. Another Bullish Year Ahead Globally, the consensus is expecting another difficult year with low oil and commodities prices among other down trends. However, things are likely to stabilize towards the end of 2016. The BRVM should be able to benefit from its low correlation with other global markets and enjoy the expected growth in the WAEMU zone. Agriculture will still be enduring a down commodities market and make it hard for these companies to perform. 2015 Stock Performances UNXC; 257.5% BNBC; 142.5% PRSC; 139.6% ABJC; 118.5% ONTBF; 114.3% TTLC; 109.5% NTLC; -9.1% SOGC; -19.7% SVOC; -25.5% PALC; -29.0% UNLC; -32.4% SPHC; -34.6% Source: BRVM Data BRVM 2015 Year in Review | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY ......................................................................... 3 WHAT HAPPENED ON THE BRVM MARKET DURING 2015 . -

The Nigerian Stock Exchange 2020 Market Review and 2021 Outlook

Contents 1. Global Capital Market Review 2020__________________________________________________ 2 2. NSE Market Performance 2020 _____________________________________________________ 3 2.1. NSE Equity Market Review _____________________________________________________ 3 2.2. NSE Fixed Income Market Review _______________________________________________ 4 2.3. NSE ETF Market Review _______________________________________________________ 4 3. NSE Strategic Performance 2020 ____________________________________________________ 6 4. Outlook for 2021 ________________________________________________________________ 9 Appendix 1: NSE Index Performance ____________________________________________________ 10 Appendix 2: NSE Market Performance __________________________________________________ 11 The Nigerian Stock Exchange 2020 Market Recap and 2021 Outlook 1 1. Global Capital Market Review 2020 The year 2020 was indeed a historic one for global capital markets. Facing buffeting headwinds, including an unprecedented pandemic, a weak global economy leading to manufacturing recessions, historically low crude oil prices, elevated geopolitical risks and social unrest – to name just a few, world markets saw sharp swings and steep losses, but largely remained resilient and orderly amid rising uncertainty. The outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19) and its rapid spread across the globe in the first quarter of the year, triggered panic selling by global investors. According to the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE), global capital markets -

LINKING MARKETS for GROWTH West African Regional Stock Exchange (BRVM) Dialogues with US Frontier Funds INTRODUCTION

LINKING MARKETS FOR GROWTH West African Regional Stock Exchange (BRVM) Dialogues With US Frontier Funds INTRODUCTION The Bourse Régionale des Valeurs Mobilières de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (BRVM) is a truly integrated regional stock exchange shared by eight West African countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. It represents an economic area of more than 100 million consumers. Because of its unique position, BRVM is a major financial player in Africa, where several groupings of stock exchanges and regional economic communities are seeking closer integration. In line with many of the regional economies, the West African market is growing fast. BRVM headquarters are in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. It was Africa’s best-performing stock exchange in 2015 when the BRVM Composite index (all-share index) rose by 17.77%. It has 39 listed companies and 36 listed debt securities. BRVM is Africa’s sixth securities exchange by market capitalization (FCFA 7.5 trillion for equities and FCFA 1.6 trillion for debt for total FCFA 9.1 trillion /USD15 billion) at end-December 2015. It was the first cross-border exchange in Africa with an integrated central depository, and it is still one of the world’s most successful integrated exchanges. It has 30 employees and is responsible for the organization of the stock market and the dissemination of market information within WAEMU (The West African Economic and Monetary Union - UEMOA in French). The BRVM is the world’s only stock exchange common to eight countries. www.brvm.org 2 HISTORY Trading began on the BRVM and clearing and settlement on the central depository and central bank on 16 September 1998. -

Press-Release-BRVM

PRESS RELEASE THE BOURSE REGIONALE DES VALEURS MOBILIERES (BRVM), A FULLY MEMBER OF THE FEDERATION OF EXCHANGES (WFE) The Regional Stock Exchange of West African Monetary Union (BRVM) is now a full member of the World Federation of Stock Exchanges (WFE). Joining eight other African stock exchanges. On May 27th, 2021, the WFE Board of Directors, approved BRVM’s full membership application. This admission crowns the efforts of the WAEMU Stock Exchange to pass the various stages to obtain the quality of full member of the most representative organization of Stock Exchanges throughout the world “On behalf of all our members and the WFE Office, I would like to extend a warm welcome to you and your colleagues as a new member of a truly global organization. I hope that you and your colleagues will benefit from the interaction with your fellow members as well as the WFE Office, and that WFE’s work will help you further develop your business and prosper” indicated Mrs. Nandini Sukumar, Chief Executive Officer of the WFE, in his letter of notification to the BRVM’s Chief Executive Officer, Dr. Edoh Kossi AMENOUNVE. – oOo – About WFE The WFE is the global industry group for exchanges and clearing houses (CCPs) around the world. We represent over 250 market-infrastructures ranging from those that operate the largest financial centres to those that run frontier markets. Founded in 1961, the Federation was set up to contribute to “the development, support and promotion of organised and regulated securities markets in order to meet the needs of the world’s capital markets in the best interests of their users”. -

The Reit Statistical and Investment Returns Reporting Manual

Securities Commission Malaysia (SCM) THE REIT STATISTICAL AND INVESTMENT RETURNS REPORTING MANUAL Page 1 Securities Commission Malaysia (SCM) DOCUMENT CONTROL Version Date Author Comments 1.0 31/03/2017 SC Updated as per 3.0.1 28/06/2021 SC tool release v3.0.1 Page 2 Securities Commission Malaysia (SCM) TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 4 PART B: REPORTING INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 5 2. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 5 3. REPORTING SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 6 FM05.M.REIT ............................................................................................................................... 7 FM16.Q.REIT .............................................................................................................................. 19 APPENDIX .................................................................................................................................................... 21 APPENDIX A: ISO CODES ......................................................................................................... -

2018 SSE Report on Progress

The SSE is a UN Partnership Program of: 2018 REPORT ON PROGRESS A paper prepared for the Sustainable Stock Exchanges 2018 Global Dialogue 2018 REPORT ON PROGRESS NOTE Additional substantive contributions were received from Richard Bolwijn (UNCTAD), Danielle Chesebrough The designations employed and the presentation of (PRI & UN Global Compact), Elodie Feller (UNEP FI) the material in this paper do not imply the expression of and Will Martindale (PRI). any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of This paper is presented as an informal contribution any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, to the discussions at the SSE Global Dialogue on 23 or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or October 2018, which takes place within the UNCTAD boundaries. World Investment Forum in Geneva, Switzerland. The views expressed in this paper are those of UNCTAD, This paper is intended for learning purposes. The the UN Global Compact, UN Environment and the PRI inclusion of company names and examples does not unless otherwise stated. constitute an endorsement of the individual exchanges or organisations by the United Nations Conference on The manuscript was edited by Mark Nicholls. The Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the UN Global report was typeset and the charts and infographics Compact, UN Environment or the Principles for designed by Pablo Cortizo. Responsible Investment (PRI). Material in this paper may be freely quoted or reprinted, ABOUT THE SSE but acknowledgement is requested. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should The SSE initiative is a UN Partnership Programme be sent to [email protected]. -

African Fixed Income and Derivatives Guidebook African Fixed Income and Derivatives Guidebook ETB

AFRIC ELOP E LO P NE DE DÉ EV ME NE D E DÉ E V M E AI VE D NT A I VE D NT IC L N IC L N R O A F R O A F F P IC U F P I C U A P N A P N E R D E R D E M F E M F A A U E U E Q N Q N N T N T A A A B B N DEVELOPMENT B T T F F N N O O E E N N D M D M E E S P S P A P A P FR O F R O IC EL I C E L AI N DE DÉV AI N D E DÉ V AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP A NK GROUP African Fixed Income and Derivatives Guidebook African Fixed Income and Derivatives Guidebook ETB LO E DE D EVE PME AIN EV D N IC EL N T R O A F F P IC U P A R N E F D E M A U E Q N N T A B T F N O E N M D E S P A P FR LO IC VE AIN DE DE AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP Temporary Relocation Agency: Angle de l’avenue du Ghana et des rues Pierre de Coubertin, Hedi Nouira BP 323 1002 Tunis Belvédère TUNISIA Contact: Group Treasurer Tel: +216 7110 2028 Fax: +216 71 33 0632 MAY E-mail: [email protected] 2010 MAY 2010 Website: www.afdb.org African Fixed Income and Derivatives Guidebook Table of Contents iii Table of Contents List of Abbreviations �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � iv Madagascar �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 89 Malawi � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 93 Foreword �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � vii Mauritania �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 97 Mauritius �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 101 Acknowledgements� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �viii Morocco � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �