AMS 14C Dating and Stable Isotope Analysis of an Earlier Neolithic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithics, Landscape and People: Life Beyond the Monuments in Prehistoric Guernsey

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Archaeology Lithics, Landscape and People: Life Beyond the Monuments in Prehistoric Guernsey by Donovan William Hawley Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Archaeology Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lithics, Landscape and People: Life Beyond the Monuments in Prehistoric Guernsey Donovan William Hawley Although prehistoric megalithic monuments dominate the landscape of Guernsey, these have yielded little information concerning the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Early Bronze Age communities who inhabited the island in a broader landscape and maritime context. For this thesis it was therefore considered timely to explore the alternative material culture resource of worked flint and stone archived in the Guernsey museum. Largely ignored in previous archaeological narratives on the island or considered as unreliable data, the argument made in this thesis is for lithics being an ideal resource that, when correctly interrogated, can inform us of past people’s actions in the landscape. In order to maximise the amount of obtainable data, the lithics were subjected to a wide ranging multi-method approach encompassing all stages of the châine opératoire from material acquisition to discard, along with a consideration of the landscape context from which the material was recovered. The methodology also incorporated the extensive corpus of lithic knowledge that has been built up on the adjacent French mainland, a resource largely passed over in previous Channel Island research. By employing this approach, previously unknown patterns of human occupation and activity on the island, and the extent and temporality of maritime connectivity between Guernsey and mainland areas has been revealed. -

The Chambered Tumulus at Heston Brake, Monmouthshire

Clifton Antiquarian Club. Volume 2 Pages 66-68 The Chambered Tumulus at Heston Brake, Monmouthshire By the REV WILLIAM BAGNALL-OAKELEY, M.A. (Read August 22nd 1888.)a In Ormerod’s Strigulensia this spot is described as the Rough Grounds, in which is a mound called Heston Brake, raised artificially on the edge of a dingle, and having a seeming elevation very much increased by natural slopes toward the North-east. This mound has a flat summit and commands a view of the Severn towards Aust; it is covered with a venerable shade of oaks and yew trees. In the centre of the summit is a space about 27ft- long by 9ft, wide, surrounded originally by thirteen rude and upright stones, now time-worn, mossed over, and matted with ivy. One is at the East-end, two at the West, and three remain at each side with spaces for the four which have been removed. It has been suggested that this is a sepulchral memorial in connection with the massacre of Harold's servants by Caradoc, in 1065, but I think we may dismiss this idea and consider its erection at a much earlier date. The mound now presents a very different appearance to what it did when Mr. Ormerod’s description was written, but as we are about to open the Chamber you will I hope have an opportunity of forming your own opinion on the subject. The Chamber is erected on a natural mound, increased by the mound of earth which originally covered the stones; elevated sites were generally chosen for these memorials of the dead in order that they might be seen from afar. -

Journal Catalogue

CATALOGUE OF THE JOURNALS STORE, LIBRARY AND HOPTON The format is journal title : date range : details of volumes on the shelf and /or notes on any that are missing in the sequence with missing volumes in italics. 'Incomplete series' means that there are many missing within the date range The journals are arranged in the store in the order as below beginning on the left. There is a list of titles on the end of each stack. 13th September 2017 GENERAL Stack A Agricultural History Review : 1967 – 2017 (Vol 65 part 1) : (2 parts a year) [1995& 1996 missing]: together with Rural History Today newsletters : Issues 19, 20, 22- 33 Amateur Historian (see under Local Historian) Ancestor, The : Vols 1 –12 and Indexes (April 1902 – Jan 1905) Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Journal of the Royal : 1947 – 1965 : together with MAN, a monthly record of Anthropological Science: 1950- 56 : incomplete series Antiquaries Journal plus indexes : 1921 (vol. 1) – 2016 (vol.96): [missing - 1947 May & June, 1954 all year, 1971 pt.2 & 1973 pt. 1] : Annual Reports for 1995 and 1996 and Book Review 1995 Antiquaries, Proceedings of the Society of : 1843 – 1920 : [missing 1858] Antiquity : 1927 (vol. 1) – 2015 (vol. 89 part 6) [missing no 312 vol. 81 part 2] Archaeologia or Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Antiquity : 1770 – 1991 : vols. 1 –109 Archaeological Institute, Proceedings of the : 1845 – 1855 Archaeological Journal : 1845 (vol. 1) – 2017 (vol. 174) : [missing 1930 (vol. 86), 1995 (vol. 152)] Archaeological Newsletter : 1948 – 1965 : [missing vol.1 no 6, vol. 2 nos. 8, 9, 10, vol. -

The Megalithic Remains at Stanton Drew

Clifton Antiquarian Club . Volume 1 Pages 14-17 The Megalithic Remains at Stanton Drew BY THE REV. H. T. PERFECT, M. A. (Read at Stanton Drew, May 28 th , 1884.) STANTON DREW, as well as Stonehenge and Avebury, is situated in the district which is known to have been occupied by the Belgae. There is a hamlet in this parish variously written as Belgetown, Belluton, or Belton, which evidently took its name from the Belgae of this district. The final syllable “ton," which is Saxon, would seem to point to the transitional period when Belgae and Saxons were contending together for the possession of the soil, at the time when this town or homestead was still an important settlement. The very name of Belge-town, the close proximity of the stone circles and the fortified camp of the Maes Knoll, seem to bespeak this immediate locality as one of the greatest importance in early Celtic days, and offer a pleasing temptation to group these three points together as collective evidence that the locality of Stanton Drew was one of the leading centres of Celtic life in England amongst the Belgae, or even centuries earlier amongst their predecessors. However this may be, the so-called druidical remains in this parish consist of one large circle adjoining a smaller one, with apparently the remains of an avenue connecting the two together. Several of the stones, both in the large circle as well as in the avenue, are missing, having been broken up in olden days when these monuments were not so carefully preserved as they now are. -

Stoke Leigh Iron Age Camp Leigh Woods, North Somerset File:///D:/Users/Ruth/Documents/PC Website/New Test Site/Articles by

Stoke Leigh Iron Age Camp Leigh Woods, North Somerset file:///D:/Users/Ruth/Documents/PC Website/new test site/Articles by ... Leigh Woods, North Somerset Fig 1 Reproduced as a Section from the Stokeleigh OS Map 2005 1:2500 Courtesy of the National Trust (Wessex Region), Leigh Woods Office, Bristol Nigel B.Bain MA, BD May 2009 There is an extensive number of diverse hillforts scattered across the West of England. The phased National Mapping Programme is currently pinpointing even more of these. Stokeleigh is the classic example of one type of hillfort construction popular during the first millennium BC, a ‘promontory’ fort. It is particularly significant in that its sturdy defences are still fairly well-preserved. What is even more remarkable about this impressive site is not only that it remains relatively unscathed 1 of 18 11/09/2020, 12:46 Stoke Leigh Iron Age Camp Leigh Woods, North Somerset file:///D:/Users/Ruth/Documents/PC Website/new test site/Articles by ... but that so little is known or has been written about it. As a result, the National Trust in collaboration with English Heritage and Natural England has recently taken the welcome decision to restore its original profile*. Particular credit must go to Mr Bill Morris, Head Warden at the NT Office in Leigh Woods and his team, for the tremendous work done in clearing the camp of its overgrowth, not to mention his own support for this project. It has been a pleasure to watch the site ‘unfold’. It has made possible the kind of accompanying photographic evidence here as never before. -

The Geology of Gloucestershire

GLOUCESTERSHIRE. [KELLY'S THE GEOLOGY OF GLOUCESTERSHIRE (Revised to :rgos.) NATURAL HISTORY AND SciENTIFIC SOCIETIES. 188o-xgor. Reports of Excursions to (r) Stroud and May Bristol Microscopical Society, Berkeley square, Clifton. Hill, May, 1870; (2) The Cheltenham District, Bristol Naturalists' Society, Berkeley square, Clifton: July, I874; ( 1) Bristol, Aust Cliff and the Mendips, Proceedings. August, r88o; (4) Cheltenham and Strand, June, Cheltenham Natural Science Society. 1897; (5) Tortworth, Avon Gorge and Aust Cliff, Bristol and Gloucestershire Archooological Society, Eastgate, May, zgor; (6) Vale of Evesham and the North Gloucester : Transactions. Cotteswolds, April, 1904, Proceedings, Geologists' Clifton Antiquarian Club : Proceedings. Association of London. Cotteswold Naturalists' Field Club, Eastgate, Gloucester: 1881. Longe, F. D.-Oolitic Polyzoa, Geol. Mag., p. 23. Proceedings. Wethered, E.-Grits andSandstones of Bristol Coal MusEuMs. field, Midland Naturalist, vol. iv., pp. 25, 59· -'Gloucester Municipal Museum, Price Memorial Hall, Muni cipal buildings. 1881. Wright, Dr. T.-Physiography and Geology of the · Cirencester: The Corinium Museum (Antiquities), and the Country round Cheltenham, Midland Naturalist, Museum of the Royal Agricultural College • vol. iv., p. I45· . Bristol Corporation Museum (and Reference Library), Queen's road, Bristol. Smithe, Rev. F.-Liassic Zones and Structure of Churchdown. Hill, Proc. Cotteswold Field Club, vol • XI., p. 247• - PUBLI<)ATIONS OF THE GOVERNMENT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY. Harrison, W. J.-Bibliography of Midland Glaciology, (I) Coloured Maps, on the scale of one inch to a mile : Trans. B'ham Nat. Hist. <f Phil. Soc., vol. ix., . Sheet Ig, Southern part of Bristol Coal-field, &c. ; Sheet 34, p. Il6. Stroud, Cirencester, &c.; Sheet 35, Bristol, Chipping s~d bury, Dnrsley, &c. -

Download This PDF File

Volume 2 Edited by Howard Williams and Liam Delaney Aims and Scope Offa’s Dyke Journal is a peer-reviewed venue for the publication of high-quality research on the archaeology, history and heritage of frontiers and borderlands focusing on the Anglo-Welsh border. The editors invite submissions that explore dimensions of Offa’s Dyke, Wat’s Dyke and the ‘short dykes’ of western Britain, including their life-histories and landscape contexts. ODJ will also consider comparative studies on the material culture and monumentality of frontiers and borderlands from elsewhere in Britain, Europe and beyond. We accept: 1. Notes and Reviews of up to 3,000 words 2. Interim reports on fieldwork of up to 5,000 words 3. Original discussions, syntheses and analyses of up to 10,000 words ODJ is published by JAS Arqueología, and is supported by the University of Chester and the Offa’s Dyke Association. The journal is open access, free to authors and readers: http://revistas.jasarqueologia.es/index. php/odjournal/. Print copies of the journal are available for purchase from Archaeopress with a discount available for members of the Offa’s Dyke Association: https://www.archaeopress.com/ Editors Professor Howard Williams BSc MA PhD FSA (Professor of Archaeology, University of Chester) Email: [email protected] Liam Delaney BA MA MCIfA (Doctoral Researcher, University of Chester) Email: [email protected] Editorial Board Dr Paul Belford BSc MA PhD FSA MCIfA (Director, Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT)) Andrew Blake (AONB Officer, Wye Valley -

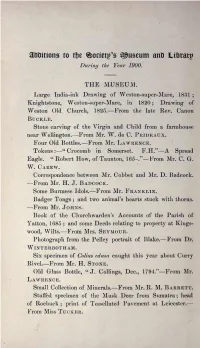

Tokens :" Crocomb in Somerset

3Dt!itions to tfje ^octetp's eguseum ant) liftratp Duriiuj the Year 1900. THE MUSEUM. India-ink of 1831 Large Drawing Weston-super-Mare, ; in 1820 of Knightstone, Weston-super-Mare, ; Drawing Weston Old Church, 1825. From the late Rev. Canon BUCKLE. Stone carving of the Virgin and Child from a farmhouse near Wellington. From Mr. W. de C. PRIDEAUX. Four Old Bottles. From Mr. LAWRENCE. Tokens :" Crocomb in Somerset. F.H." A Spread " Eagle. Robert How, of Taunton, 165-." From Mr. C. G. W. CAREW. Correspondence between Mr. Cobbet and Mr. D. Badcock. From Mr. H. J. BADCOCK. Some Burmese Idols. From Mr. FRANKLIN. animal's stuck with thorns. Badger Tongs ; and two hearts From Mr. JOHNS. Book of the Churchwarden's Accounts of the Parish of 1685 and to at Yatton, ; some Deeds relating property Kings- wood, Wilts. From Mrs. SEYMOUR. Photograph from the Pelley portrait of Blake. From Dr. WlNTERBOTHAM. Six specimen of Colias edusa caught this year about Curry Rivel. From Mr. H. STONE. " Old Glass Bottle, J. Collings, Dec., 1794." From Mr. LAWRENCE. Small Collection of Minerals. From Mr. R. M. BARRETT. of head Stuffed specimen the Musk Deer from Sumatra ; of at Leicester. Roebuck ; print of Tessellated Pavement From Miss TUCKER. Additions to the Library. 49 THE LIBRARY. Excerpts from Wills Chew Magna, Chew Stoke, Bishop's Norton and 5 S'ltton, Hautville, Dundry ; vols., manuscript, in 1 Index. From Mr. F. A. WOOD. Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society, vol. v, pt. 6. The First Bishop of Bath and H ells. From the author, Mr. -

Early Medieval Wales – Research Framework 2016

EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES – RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 2016 KEY ADDITIONS TO THE BIBLIOGRAPHY 2010–2016 Anguilano, L., Timberlake, S. and Rehren, T. (2010) ‘An early medieval lead-smelting bole from Banc Tynddol, Cwmystwyth, Ceredigion’, Historical Metallurgy 44, 85–103 Brett, M., Holbrook, N. and McSloy, E. R. (2015), ‘Romano-British and medieval occupation at Sudbrook Road, Portskewett, Monmouthshire: excavations in 2009’, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 31, 3–43 Brown, A., Turner, R. and Pearson, C. (2010), ‘Medieval fishing structures and baskets at Sudbrook Point, Severn Estuary, Wales’, Medieval Archaeology, 54, 346–61 Caseldine, A. E. (2013), ‘Pollen analysis at Craig y Dullfan and Banc Wernwgan and other recent palaeoenvironmental studies in Wales’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 162, 275–307 Caseldine, A. E. (2015), ‘Environmental change and archaeology – a retrospective view’, Archaeology in Wales, 54, 3–14 Chadwick, A. M. and Catchpole, T. (2010), ‘Casing the net wide: mapping and dating fish traps through the Severn Estuary Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey’, Archaeology in the Severn Estuary, 21, 47–80 Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013), Wales and the Britons 350–1064 (Oxford) Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013), ‘Reflections on early-medieval Wales’, Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, n. s. 19, 7–23 Comeau, R. (2012), ‘From tref(gordd) to tithe: identifying settlement patterns in a north Pembrokeshire parish’, Landscape History, 33:1, 29- 44 Comeau, R. (2014), ‘Bayvil in Cemaes: an early medieval assembly site in south-west Wales? ’, Medieval Archaeology, 58, 270–84 Comeau, R. (2015), ‘Long-cist graves at Cwm yr Eglwys Church, Pembrokeshire (SN 01496 40079), a belated note about a 1981 rescue excavation’, Archaeology in Wales, 54, 159–63 Crane, P. -

Archaeological Papers

INDEX OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAPERS PUBLISHED JN 1S97 [BEING THE SEVENTH ISSUE OF THE SERIES AND COMPLETING THE INDEX FOR THE PERIOD 1891-97] PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES. 1898 HARRISON AND SONS, PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HER MAJESTY, ST. MARTIN'S LANE, LONDON. CONTENTS, [Those Transactions marked with an asterisk * in the following list are now for th first time included in the index, the others are continuations from the indexes of 1891-96. Transactions included for the Urst time are indexed from 1891 onwards.] Anthropological Institute, Journal, vol. xxvi, pts. 3 and 4, vol. xxvii, pts. 1 and 2. Antiquaries, London, Proceedings of the Society, 2nd sei\, vol. xvi, pts. 3 and 4. Antiquaries, Ireland, Proceedings of Royal Society of, 5th ser., vol. vii. Antiquaries, Scotland, Proceedings of the Society, vol. xxxi. Arcliaeologia, vol. lv, pt. 2. Archteologia iEliana, vol. xix, pts. 1, 2, and 3. Archaeologia Cambrensis, 5th ser., vol. xiv. Archaeological Journal, vol. liv. *Associated Architectural Societies, Transactions, vol. xxiii, pts. 1 and 2. Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Archaeological Journal, vol. iii. Biblical Archaeology, Society of, Transactions, vol. xix. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Transactions, vol. xix, and xx, pt. 1. British Archaeological Association, Journal, New Series, vol. iii. British Architects, Royal Institute of, Journal, 3rd ser., vol. iv Buckinghamshire, Records of, vol. vii, pts. 4, 5, and 6. Cambridge Antiquarian Society, Transactions, vol. ix, pt. 3. Chester and North Wales Architectural, Archaeological and Historical Society, Transactions, vol. vi, pt. 1. Clifton Antiquarian Club, Proceedings, vol. -

Stones in Substance, Space and Time

Introduction: stones in substance, space and time Item Type Book chapter Authors Williams, Howard; Kirton, Joanne; Gondek, Meggen M. Citation Williams, H., Kirton, J. & Gondek, M. (2015). Introduction: stones in substance, space and time, in. H. Williams, J. Kirton and M. Gondek. (Eds.). Early Medieval Stone Monuments: Materiality, Biography, Landscape (pp. 1-34). Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. Publisher Boydell Press Download date 01/10/2021 21:56:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/594442 Williams, H., Kirton, J. and Gondek, M. 2015. Introduction: stones in substance, space and time, in. H. Williams, J. Kirton and M. Gondek (eds) Early Medieval Stone Monuments: Materiality, Biography, Landscape. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, pp. 1-34. http://www.boydellandbrewer.com/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=14947 Introduction: Stones in Substance, Space and Time Howard Williams, Joanne Kirton & Meggen Gondek A triad of research themes – materiality, biography and landscape – provide the distinctive foci and parameters of the contributions to this book. The chapters explore a range of early medieval inscribed and sculpted stone monuments from Ireland (Ní Ghrádaigh and O’Leary), Britain (Gondek, Hall, Kirton and Williams) and Scandinavia (Back Danielsson and Crouwers). The chapters together show how these themes enrich and expand the interdisciplinary study of early medieval stone monuments, in particular revealing how a range of different inscribed and sculpted stones were central to the creation and recreation of identities and memories for early medieval individuals, families, households, religious and secular communities and kingdoms. Many narratives can be created about early medieval stone monuments (e.g. Hawkes 2003a; Orton and Wood 2007). -

Rock Art and Trade Networks: from Scandinavia to the Italian Alps

Open Archaeology 2020; 6: 86–106 Original Study Lene Melheim*, Anette Sand-Eriksen Rock Art and Trade Networks: From Scandinavia to the Italian Alps https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2020-0101 Received December 27, 2019; accepted February 28, 2020 Abstract: This article uses rock art to explore potential bonds between Scandinavia and Italy, starting in the second half of the third millennium BCE with the enigmatic Mjeltehaugen burial monument in coastal western Norway and its striking rock art images, and ending in the first millennium BCE with ship motifs in inland Val Camonica, Italy. While the carved dagger on the Mjeltehaugen slab is unique in its Nordic setting, such weapon depictions are frequently seen on the Continent, e.g. in South Tyrol, and more often in later Nordic rock art. Strong evidence of trade relations between the Italian Alps and Scandinavia is found c. 1500–1100 BCE when the importation of copper from South Tyrol coincided with two-way transmission of luxury items, and again in a different form, c. 1000–700 BCE when strong similarities in burial traditions between the two areas may be seen as evidence of direct cultural connections or a shared cultural koiné. In order to understand the social fabric of these relations and how they unfolded through time, the authors discuss several different models of interaction. It is hypothesised that rock art practices played a role in establishing and maintaining durable social relations, through what we consider to be a two-way transmission of symbolic concepts and iconography during seasonal meetings related to trade and travel.