Guide to Housing, Land and Property in the Gaza Strip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Scotland Still Needs an 'Ending Homelessness' Action Plan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Policy Reviews 131 Delivering the Right to Housing? Why Scotland Still Needs an ‘Ending Homelessness’ Action Plan Isobel Anderson Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Stirling, Scotland, UK \ Abstract_ In 2018, the Scottish Government launched the ‘Ending Homelessness Together Action Plan’, just 6 years after the earlier ‘2012 target’ for implementation of the previous major review of homelessness policy. Scotland had introduced a modernised legislative framework for homeless- ness, with the Homelessness etc. (Scotland) Act of 2003, strengthening the legal rights of homeless people to assistance with housing. Using a policy analysis framework, this paper revisits the impact of the earlier legislation, identifying perceived gaps in implementation, which framed the context for further review. The paper examines the work programme of the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group (HARSAG), which contributed to policy review, and outlines key components of the 2018 action plan. The analysis reflects critically on the potential for meaningful progress on ending homeless- ness over the five years from 2018-2023. Given international interest in prior homelessness policy in Scotland, this research was conducted to inform a European and wider international audience of the further ambitions to end homelessness in Scotland. The study adopted desk-based methods, drawing on published administrative data on homelessness, publicly available policy and practice documents, and the wider research evidence on homelessness. The analysis demonstrates that while the Scottish approach still compares favourably internationally, robust commitment to policy delivery, as well as monitoring of implementation and review of outcomes all remain essential to ensure policy effectiveness. -

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

Armed Conflicts Report - Israel

Armed Conflicts Report - Israel Armed Conflicts Report Israel-Palestine (1948 - first combat deaths) Update: February 2009 Summary Type of Conflict Parties to the Conflict Status of the Fighting Number of Deaths Political Developments Background Arms Sources Economic Factors Summary: 2008 The situation in the Gaza strip escalated throughout 2008 to reflect an increasing humanitarian crisis. The death toll reached approximately 1800 deaths by the end of January 2009, with increased conflict taking place after December 19th. The first six months of 2008 saw increased fighting between Israeli forces and Hamas rebels. A six month ceasefire was agreed upon in June of 2008, and the summer months saw increased factional violence between opposing Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah. Israel shut down the border crossings between the Gaza strip and Israel and shut off fuel to the power plant mid-January 2008. The fuel was eventually turned on although blackouts occurred sporadically throughout the year. The blockade was opened periodically throughout the year to allow a minimum amount of humanitarian aid to pass through. However, for the majority of the year, the 1.5 million Gaza Strip inhabitants, including those needing medical aid, were trapped with few resources. At the end of January 2009, Israel agreed to the principles of a ceasefire proposal, but it is unknown whether or not both sides can come to agreeable terms and create long lasting peace in 2009. 2007 A November 2006 ceasefire was broken when opposing Palestinian groups Hamas and Fatah renewed fighting in April and May of 2007. In June, Hamas led a coup on the Gaza headquarters of Fatah giving them control of the Gaza Strip. -

Strateg Ic a Ssessmen T

Strategic Assessment Assessment Strategic Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Volume 19 Volume The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | No. 4 No. Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | January 2017 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities Emily B. Landau and Ephraim Asculai Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Abstracts | 3 The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century | 9 Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | 29 Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | 43 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? | 57 Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army | 67 Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation | 79 Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects | 93 Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations | 103 Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities | 117 Emily B. -

The Cabinet Resolution Regarding the Disengagement Plan

The Cabinet Resolution Regarding the Disengagement Plan 6 June 2004 Addendum A - Revised Disengagement Plan - Main Principles Addendum C - Format of the Preparatory Work for the Revised Disengagement Plan Addendum A - Revised Disengagement Plan - Main Principles 1. Background - Political and Security Implications The State of Israel is committed to the peace process and aspires to reach an agreed resolution of the conflict based upon the vision of US President George Bush. The State of Israel believes that it must act to improve the current situation. The State of Israel has come to the conclusion that there is currently no reliable Palestinian partner with which it can make progress in a two-sided peace process. Accordingly, it has developed a plan of revised disengagement (hereinafter - the plan), based on the following considerations: One. The stalemate dictated by the current situation is harmful. In order to break out of this stalemate, the State of Israel is required to initiate moves not dependent on Palestinian cooperation. Two. The purpose of the plan is to lead to a better security, political, economic and demographic situation. Three. In any future permanent status arrangement, there will be no Israeli towns and villages in the Gaza Strip. On the other hand, it is clear that in the West Bank, there are areas which will be part of the State of Israel, including major Israeli population centers, cities, towns and villages, security areas and other places of special interest to Israel. Four. The State of Israel supports the efforts of the United States, operating alongside the international community, to promote the reform process, the construction of institutions and the improvement of the economy and welfare of the Palestinian residents, in order that a new Palestinian leadership will emerge and prove itself capable of fulfilling its commitments under the Roadmap. -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

Jnf Blueprint Negev: 2009 Campaign Update

JNF BLUEPRINT NEGEV: 2009 CAMPAIGN UPDATE In the few years since its launch, great strides have been made in JNF’s Blueprint Negev campaign, an initiative to develop the Negev Desert in a sustainable manner and make it home to the next generation of Israel’s residents. In Be’er Sheva: More than $30 million has already been invested in a city that dates back to the time of Abraham. For years Be’er Sheva was an economically depressed and forgotten city. Enough of a difference has been made to date that private developers have taken notice and begun to invest their own money. New apartment buildings have risen, with terraces facing the riverbed that in the past would have looked away. A slew of single family homes have sprung up, and more are planned. Attracted by the River Walk, the biggest mall in Israel and the first “green” one in the country is Be’er Sheva River Park being built by The Lahav Group, a private enterprise, and will contribute to the city’s communal life and all segments of the population. The old Turkish city is undergoing a renaissance, with gaslights flanking the refurbished cobblestone streets and new restaurants, galleries and stores opening. This year, the municipality of Be’er Sheva is investing millions of dollars to renovate the Old City streets and support weekly cultural events and activities. And the Israeli government just announced nearly $40 million to the River Park over the next seven years. Serious headway has been made on the 1,700-acre Be’er Sheva River Park, a central park and waterfront district that is already transforming the city. -

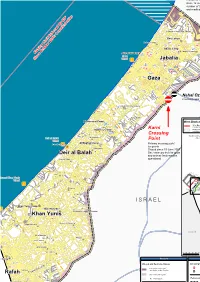

Gaza Strip Closure Map , December 2007

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Access and Closure - Gaza Strip December 2007 s rd t: o i t c im n N c L e o Erez A . m F g m t i lo n . i s s i n m h Crossing Point h t: in O s 0 m i s g i 2 o le F im i A Primary crossing for people (workers C L m re i l a and traders) and humanitarian personnel in g a rt in c Closed for Palestinian workers e h ti s u since 12 March 2006 B i a 2 F Closed for Palestinians 0 n 0 2 since 12 June 2007 except for a limited 2 1 number of traders, humanitarian workers and medical cases s F le D i I m y l B a d ic e t c u r a Al Qaraya al Badawiya al Maslakh ¯p fo n P Ç 6 n : ¬ E 6 it 0 Beit Lahiya 0 im 2 P L r Madinat al 'Awda e P ¯p "p ¯p "p g b Beit Hanoun in o ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p h t Jabalia Camp ¯p ¯p ¯p P ¯p s c p ¯p ¯p i p"p ¯¯p "pP 'Izbat Beit HanounP F O Ash Shati' Camp ¯p " ¯p e "p "p ¯p ¯p c Gaza ¯Pp ¯p "p n p i t ¯ Wharf S Jabalia S t !x id ¯p S h s a a "p m R ¯p¯p¯p ¯p a l- ¯p p r A ¯p ¯ a "p K "p ¯p l- ¯p "p E ¯p"p ¯p¯p"p ¯p¯p ¯p Gaza ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p t S ¯p a m ¯p¯p ¯p ra a K l- Ç A ¬ Nahal Oz ¯p ¬Ç Crossing point for solid and liquid fuels p t ¯ t S fa ¯p Al Mughraqa (Abu Middein) ra P r A e as Y Juhor ad Dik ¯pP ¯p LEBANON An Nuseirat Camp ¯p ¯p West Bank and Gaza Strip P¯p ¯p ¯p West Bank Barrier (constructed and planned) ¯p ¯p ¯p Al Bureij Camp¯p ¯p Karni Areas inaccessible to Palestinians or subject to restrictions ¯p¯pP¯p Crossing `Akko !P MEDITERRANEAN Az Zawayda !P Deir al Balah ¯p P Point SEA Haifa Tiberias !P Wharf Nazareth !P ¯p Al Maghazi Camp¯p¯p Deir al Balah Camp Primary -

Light at the End of Their Tunnels? Hamas & the Arab

LIGHT AT THE END OF THEIR TUNNELS? HAMAS & THE ARAB UPRISINGS Middle East Report N°129 – 14 August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TWO SIDES OF THE ARAB UPRISINGS .................................................................... 1 A. A WEDDING IN CAIRO.................................................................................................................. 2 B. A FUNERAL IN DAMASCUS ........................................................................................................... 5 1. Balancing ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Mediation ..................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Confrontation ............................................................................................................................... 7 4. The crossfire................................................................................................................................. 8 5. Competing alliances ................................................................................................................... 10 C. WHAT IMPACT ON HAMAS? ...................................................................................................... -

30 October 2020 SDEROT Shabbat Greetings to Everyone, I Feel That The

Friday Evening Message – 30 October 2020 SDEROT Shabbat greetings to everyone, I feel that the Friday night message is a great idea by the community and hopefully it will continue beyond this time of craziness. I have recently started a new project myself which is reconnecting with friends who I haven’t spoken to for a while, there is nothing as nice as getting a message from someone who we haven’t heard from in ages, especially during these difficult days. So I have started to contact someone every week just to wish them Shabbat Shalom and check in with them. One of those who I have recently reconnected with was a dear friend Stewart Ganullin who happens to be the CEO of an organisation who I volunteered with on my many trips to Israel. Stewart is the amazing head of Hope for Sderot based in what is sadly known as the rocket capital of the world. The small “museum” of Kassam, Grad and Kadyusha rockets in the cities police station is a reminder of the over 16000 rockets to be fired from the nearby Gaza Strip to the civilian population 2km away in Sderot. The “rocket museum” located at Sderot police station. In the year preceding, to the year following, the Gush Katif disengagement rocket attacks on Sderot and surrounding Western Negev increased by ten-fold. Even though those who could afford to flee reducing the city population to less than 20000 it was allowed to retain city status and at the last year’s census had risen to almost 28000. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip FRONT COVER United Nations Environment Programme First published in March 2006 by the United Nations Environment Programme. © 2006, United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 92-807-2697-8 Job No.: DEP/0810/GE United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This revised edition includes grammatical, spelling and editorial corrections to a version of the report released in March 2006. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material herein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher or the participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimination of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photographs in this publication were taken by the UNEP Gaza assessment mission team. Cover Design and Layout: Matija Potocnik