Trials and Tribulations in London Below

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{TEXTBOOK} Anansi Boys Ebook Free Download

ANANSI BOYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Neil Gaiman | 416 pages | 11 Jul 2011 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060515195 | English | New York, NY, United States Anansi Boys (American Gods, #2) by Neil Gaiman Gaiman turned his attention to African mythology and the figure of Anansi the spider god. Having already made a scene-stealing appearance in the award-winning American Gods , the irresistible Mr Nancy makes a triumphant return in this witty romp of a novel — perfect for fans of Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett. Now you merely have to do something just as beautiful and just as ground-breaking. Inside, fully illustrated, original black-and-white chapter headings tell their own folktale — all of which are especially fitting for a book about the power and vitality of stories. Spider was the cool one; he was the other one. Bereavement is a time of upheaval and for Fat Charlie Nancy the changes are practically seismic. Not only does he discover that his embarrassing old dad was actually Anansi the African trickster god, his life is about to be invaded and turned upside down by Spider, the magical twin brother he never knew he had. As well as helping to inspire the book, Lenny Henry provided advice and insight on Caribbean syntax and dialogue, helping to ensure that the voices of the characters sounded authentic. His work demonstrates exactly how wild and varied the field can be, from uprooting fairy tales in Stardust to exposing the fantastical underbelly of London in Neverwhere. Neil Gaiman is a critically acclaimed writer of short fiction, novels, comic books, graphic novels, audio theatre and films. -

PDF Download the Sandman Overture

THE SANDMAN OVERTURE: OVERTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. H. Williams, Neil Gaiman | 224 pages | 17 Nov 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401248963 | English | United States The Sandman Overture: Overture PDF Book Writer: Neil Gaiman Artist: J. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. This would have been a better first issue. Nov 16, - So how do we walk the line of being a prequel, but still feeling relevant and fresh today on a visual level? Variant Covers. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. Click on the different category headings to find out more. Presented by MSI. Journeying into the realm of his sister Delirium , he learns that the cat was actually Desire in disguise. On an alien world, an aspect of Dream senses that something is very wrong, and dies in flames. Most relevant reviews. Williams III. The pair had never collaborated on a comic before "The Sandman: Overture," which tells the story immediately preceding the first issue of "The Sandman," collected in a book titled, "Preludes and Nocturnes. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. It's incredibly well written, but if you are looking for that feeling you had when you read the first issue of the original Sandman series, you won't find it here. Retrieved 13 March Logan's Run film adaptation TV adaptation. Notify me of new posts by email. Dreams, and by extension stories as we talked about in issue 1 , have meaning. Auction: New Other. You won't get that, not in these pages. -

An Investigation of the Contribution of Latter-Day Revelation to an Understanding of the Atonement of Christ

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1956 An Investigation of the Contribution of Latter-Day Revelation to an Understanding of the Atonement of Christ Eldon R. Taylor Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Taylor, Eldon R., "An Investigation of the Contribution of Latter-Day Revelation to an Understanding of the Atonement of Christ" (1956). Theses and Dissertations. 5166. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5166 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. AN investigation OF THE contribution OF natterLATTERDAYLATTERLATTERL DAY revelation TO AN understanding OF THE ATONEMENT OF CHRIST A THESISTHE SIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF RELIGION OF BRIGHAM YOUNG university IN PARTIAL fulfillment OF THE requirements FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS f 0 od by ELDON R TAYLOR 1956 acknowledgments sincere appreciation to my wife whose willingness to serve her family and sacrifice personal ambitions to further develop her outstanding talents in music and art has made this small achievement possible to president william E berrett for his thoughtful considera- tion and -

7-26-18 2019 Frederick Speaker Series Lineup

Media Contact: Barbara Hiller Manager of Marketing, Weinberg Center for the Arts 301-600-2868 | [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2019 Frederick Speaker Series Lineup Announced FREDERICK, MD, July 26, 2018 — Entering its seventh year, the Frederick Speaker Series has developed a reputation for bringing world-class speakers to the Frederick community. The 2019 lineup includes; Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Ronan Farrow, actress and LGBT advocate, Laverne Cox, actor and literacy advocate, Levar Burton and international bestselling author, Neil Gaiman. All series events are held at the Weinberg Center for the Arts. Tickets for all four speakers will go on sale to Weinberg Center members on Thursday, August 9 at 10:00 AM and to the general public on Thursday, August 16 at 10:00 AM. Tickets may be purchased online at weinbergcenter.org, by calling the Weinberg Center Box Office at 301-600-2828, or in person at 20 W. Patrick Street in Frederick, Maryland. For more information about becoming a Weinberg Center member and gaining early access to tickets, please visit weinbergcenter.org/support#membership. A separately-ticketed meet-and-greet reception will take place immediately following each presentation. These exclusive events provide a chance for fans to meet the speakers, take pictures, and obtain autographs. All proceeds from the meet-and-greet receptions will benefit children’s programs at Frederick County Public Libraries. Ronan Farrow | Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 7:30 PM Born in 1987 to actress Mia Farrow and filmmaker Woody Allen, Ronan Farrow achieved early notoriety as a child prodigy, skipping grades and starting college at age 11. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

The Image of Contemporary Society in Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere

Pobrane z czasopisma New Horizons in English Studies http://newhorizons.umcs.pl Data: 08/10/2021 04:42:57 New Horizons in English Studies 1/2016 LITERATURE • Julia Kula Maria Curie-SkłodowSka univerSity (uMCS) in LubLin [email protected] The Image of Contemporary Society in Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere Abstract. Neil Gaiman’s urban fantasy novel Neverwhere revolves around some problematic aspects prevalent in the contemporary world, such as an iniquitous discrepancy between social classes or a problematic attitude to history. The artistic universes created by Gaiman are instrumental in con- veying a complex condition of postmodern society. Although one of the represented worlds, London Above, is realistic and the other, London Below, is fantastic, both are suggestive of the contemporary social situation, citizens’ shared values and aspirations. Only when considered together can they reveal a comprehensive image of what the community accepts and what it rejects as no longer consistent with commonly held beliefs. UMCS The disparities in the representations of London Above and London Below refer to the division into the present and the past. The realistically portrayed metropolis is the embodiment of contemporary times. The fantastic London Below epitomises all that is ignored or rejected by London Above. The present study is going to discuss the main ideas encoded in the semiotic spaces created by Neil Gaiman, on the basis of postmodern theories. I am going to focus on how the characteristic features of postmodern fiction, such as the use of fantasy and the application of the ontological dominant, by highlighting the boundaries between London Above and London Below affect the general purport of the work. -

Anansi Boys Neil Gaiman

ANANSI BOYS NEIL GAIMAN ALSO BY NEIL GAIMAN MirrorMask: The Illustrated Film Script of the Motion Picture from The Jim Henson Company(with Dave McKean) The Alchemy of MirrorMask(by Dave McKean; commentary by Neil Gaiman) American Gods Stardust Smoke and Mirrors Neverwhere Good Omens(with Terry Pratchett) FOR YOUNG READERS (illustrated by Dave McKean) MirrorMask(with Dave McKean) The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish The Wolves in the Walls Coraline CREDITS Jacket design by Richard Aquan Jacket collage from Getty Images COPYRIGHT Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted material: “Some of These Days” used by permission, Jerry Vogel Music Company, Inc. Spider drawing on page 334 © by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved. This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. ANANSI BOYS. Copyright© 2005 by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of PerfectBound™. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gaiman, Neil. -

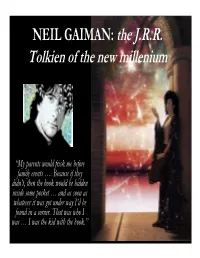

Tolkien of the New Millenium NEIL GAIMAN: the J.R.R

NEIL GAIMAN: the J.R.R. Tolkien of the new millenium “My parents would frisk me before family events …. Because if they didn’t, then the book would be hidden inside some pocket … and as soon as whatever it was got under way I’d be found in a corner. That was who I was … I was the kid with the book.” ABOUT THE AUTHOR • Nov. 10th, 1960 (came into being) • Polish-Jewish origin (born in England) • Early influences: – C.S. Lewis – J.R.R. Tolkien – Ursula K. Le Guin • Pursued journalism as a career, focused on book reviews and rock journalism • 1st book a biography of Duran Duran, 2nd a book of quotations (collaborative) • Became friends with comic book writer Alan Moore & started writing comics GAIMAN’S WORKS • Co-author (with Terry Pratchett) of Good Omens, a very funny novel about the end of the world; international bestseller • Creator/writer of monthly DC Comics series Sandman, won 9 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards and 3 Harvey Awards – #19 won 1991 World Fantasy Award for best short story, 1st comic ever to win a literary award – Endless Nights 1st graphic novel to appear on NYT bestseller list • American Gods in 2001; NYT bestselling novel, won Hugo, Nebula, Bram Stoker, SFX, and Locus awards • Wrote the script for Beowulf with Roger Avary OTHER WORKS • Mirrormask film released in late 2005 • Designed a six-part fantastical series for the BBC called Neverwhere, aired in 1996. The novel Neverwhere was released in 1997 and made into a film. • Coraline and The Wolves in the Walls are two award-winning children’s books; Coraline is being filmed, with music provided by They Might Be Giants, and TWW is being made into an opera. -

Spectral Latinidad: the Work of Latinx Migrants and Small Charities in London

The London School of Economics and Political Science Spectral Latinidad: the work of Latinx migrants and small charities in London Ulises Moreno-Tabarez A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2018 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 93,762 words. Page 2 of 255 Abstract This thesis asks: what is the relationship between Latina/o/xs and small-scale charities in London? I find that their relationship is intersectional and performative in the sense that political action is induced through their interactions. This enquiry is theoretically guided by Derrida's metaphor of spectrality and Massey's understanding of space. Derrida’s spectres allow for an understanding of space as spectral, and Massey’s space allows for spectres to be understood in the context of spatial politics. -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

The Clash of Culture in Neil Gaiman's American Gods

LEXICON Volume 5, Number 2, October 2018, 139-151 The Clash of Culture in Neil Gaiman's American Gods Naya Fauzia Dzikrina*, Ahmad Munjid Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aims to examine the portrayal of cultural clash in Neil Gaiman’s novel, American Gods. More specifically, this research aims to identify what cultures are clashing and why they clash, and also to understand how the situation of cultural clash affects the lives and attitudes of the characters. This research also explores how the novel relates to cases of cultural clash happening in the current American society. This research is conducted using the framework of several sociological theories to understand the different forms of effects of cultural clash. The main issue presented in the novel is the conflict between the old gods, who represent society’s traditional beliefs, and the new gods, who represent the shift of culture in modern America. This conflict symbolizes how the two ideals, tradition and modernity, are competing in the American society today. The challenges the old gods face can also be seen as a portrayal of the immigrant experience, where they experience effects of cultural clash also commonly experienced by immigrants: cultural displacement, identity crisis, and conflict. The main finding of this research is that a person or group who experiences cultural clash will face a struggle where they must compromise or negotiate their cultural identity in order to be part of their current community. This is done as a way to survive and thrive in their environment. Keywords: conflict, cultural clash, displacement, identity, modernity, tradition. -

Using Fiction to Support Gender Equality: the Case for Neverwhere

Högskolan i Halmstad Sektionen för lärarutbildning Engelska 61-90 hp - Using Fiction to support gender equality: the case for Neverwhere and Pride and Prejudice - Karen Gustavsson C-uppsats Handledare: Anna Fåhraeus 2 Abstract This essay is a discussion of how fiction can be used in teaching English as a second language to promote gender equality. The novels analyzed are Pride and Prejudice and Neverwhere. Firstly, the term gender is explained. Secondly, there is some research that demonstrates how gender is a social construction. The focus of this essay is on the role of the teacher, since his or her expectations and his or her way of interacting with students is crucial to promote gender equality in the classroom. Additionally, there is a discussion of the strategies that can help the teacher to detect bias in the teaching material. Furthermore, there are suggestions on how the novels can be used to promote gender equality through using the content-based approach. 3 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 4 Literature overview ................................................................................................... 5 Method ...................................................................................................................... 7 What is gender? ......................................................................................................... 8 The role of the teacher .............................................................................................