Battle of the Ford of the Biscuits: Metal Detecting Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200 Dpi) Lane 1:40000

580000 585000 590000 595000 600000 7°48'0"W 7°45'0"W 7°42'0"W 7°39'0"W 7°36'0"W 7°33'0"W 7°30'0"W 7°27'0"W 7°24'0"W GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR151 Product N.: 05ENNISKILLEN, v2, English Enniskillen - UNITED KINGDOM Flood - Pre-event situation Reference Map Strabane h h g g a ! u e o L N Omagh C 04 Dru reeby u ms Sc 0 r R lo 0 L r o e d o 0 a a 0 w i d Ro L (! n o e 0 0 u L gh r 0 0 o R u (! Er Kesh 3 3 g n B o d M h e la 0 0 e a a lv Belleek ck North 6 d 6 w o in NORTH B a Sea R a ATLANTIC Inner n te a Seas n r, o 03 OCEAN C 05 N Belfast " (! ^ 0 Enniskillen !Ballycassidy ' Ireland Irish Sea 4 Fermanagh 2 ° U 4 United L p F 5 o p Lisnaskea Coa i ! n E u e Kingdom Knockmanoul ! g r ! g r (! e n h 06 N e " r ^ p 0 ' o London 4 Ballinamallard 2 s L ° t A English Channel o 4 R France l u 5 l o e L g is a n d h R ea d o d Road Annalee, ad labby C Erne 10 n km e anno e Sh n m h d g a a ll o u R M !Tempo !Ballyreagh Cartographic Information op Drumscoll Full color ISO A1, medium resolution (200 dpi) Lane 1:40000 d a o 0 0.5 1 2 R tt km o T r u C l ly re d a Grid: WGS 1984 UTM zone 29N map coordinate system a g o h oad R R h R l o ag Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system e a re p C ± d a h C a o Legend C 0 M 0 0 on 0 0 R ea 0 5 oa oad 5 2 d po R 2 0 Tem ! 0 General Information Hydrology 6 6 Area of Interest Dam ad o Ro C oh r B o a Settlements River g h r ! i Populated Place m Stream a R r o a d a w Transportation d a N o o " 0 Lake B R ' 1 2 Primary Road ° 4 5 River Secondary Road N " 0 ' !Drumboy 1 2 ° 4 d 5 na Roa !Enniskillen Tras agh son R am R ig S ad o g Ro a d d a o R s d C ! o l o o R g C w o h h d o a t M o s a d l s R g o e o A l R e r b y e i v b s e e r l e e a o l v y i n i r E o Exposure within the AOI e S R h k R g e u o o Unit of measurement Total in AOI a L d d a D d o r oa Estimated population No. -

Measuring What Matters

Measuring What Matters A pilot project carried out by Rural Community Network (NI) & Rose Regeneration Key Findings (See Page P10) 1. Every project analysed is delivering a positive social return. 2. Every project delivered several valuable and common outcomes. 3. Every project plans to use their SROI assessment as a way of demonstrating impact to current and potential new funders. 4. Projects value the importance of partnership working & collaboration to achieve results. 5. Measuring Social Value assists groups in better planning and delivery of projects. 6. Outcomes are as important as targets when planning project delivery. 7. Using this approach, is a user friendly, efficient way for small community/voluntary groups to evidence and measure their impact. 8. Funding bodies should encourage funded groups to adopt this model of measuring Social Value. 9. Groups that measure their impact get validation in the work that they carry out. 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction & Background to the Project 3 2. Identifying the Projects & Methodology 6 3. Key Findings 10 4. Conclusion 13 Project Summaries 1. Cleenish Community Association 14 2. Lawrencetown, Lenaderg &Tullylish Community Association 20 3. Lislea Community Association 26 4. Mid Ulster Women’s Aid 32 5. Out and About 38 6. TIDAL 44 2 Introduction In Northern Ireland government departments, local councils and funders of the community / voluntary sector are increasingly asking community groups to demonstrate their effectiveness in terms of value for money that is being invested in them, as well as their real impact. For community groups, showing their value for money and social value is a positive thing. -

Co. Fermanagh

Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology Queen’s University Belfast Data Structure Report No. 103 Excavations at Arney, Co. Fermanagh # Queen’s University Belfast Excavations at Arney, Co. Fermanagh (H 20725 37002) AE/14/01E Brian Sloan and Dermot Redmond Contents 1. Summary 1 2. Introduction 4 3. Account of the excavations 8 4. Account of the metal detecting survey 35 5. Conclusion 41 6. Recommendations for further work 42 7. Bibliography 43 8. Appendix 1: Context Register 45 9. Appendix 2: Harris Matrices 47 10. Appendix 3: Field Drawing Register 50 11. Appendix 4: Finds Register 51 12. Appendix 5: Photographic Register 53 Figures Figure # Detail Page Figure 1: General location map. 3 Figure 2: Google screen grab showing location of Arney. 3 Figure 3: 1st edition 6 inch OS map dated to 1835. 5 Figure 4: 3rd edition 6 inch OS map dated to c.1907. 6 Figure 5: Sites and Monuments details within 1 km of 7 the excavation area. Figure 6: Arney Schoolhouse on 3rd edition map 9 Figure 7: South-facing section of Trench One. 11 Figure 8: Post-excavation plan of Trench One 11 Figure 9: Schematic plan of features associated with the 16 Schoolhouse. Figure 10: Proposed development of Robert Lamb’s house 23 Figure 11: Plan of typical hearth-lobby house 24 Figure 12: Location of Trench Two on 3rd edition map 25 Figure 13: Post-excavation plan of Trench Two 31 (Robert Lambs house) Figure 14: Location of Trench Two on 3rd edition map 32 Figure 15: Post-excavation plan of Trench Three 34 Figure 16: Results of the metal detecting survey 38 Figure 17: Results of the metal detecting survey overlaid 39 On the 1st edition OS map Figure 18: Arney landscape showing the location of 40 the musket shot identified through metal detector survey Plates Plate # Detail Page Plate 1: View of probable demolition deposit (Context No. -

A Revised List of the Executive Assets in County Fermanagh Is Provided and an Update Will Be Provided to the Assembly Library

Conor Murphy MLA Minister of Finance Clare House, 303 Airport Road West Belfast BT3 9ED Mr Seán Lynch MLA Northern Ireland Assembly Parliament Buildings Stormont AQW: 6772/16-21 Mr Seán Lynch MLA has asked: To ask the Minister of Finance for a list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh. ANSWER A revised list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh is provided and an update will be provided to the Assembly Library. Signed: Conor Murphy MLA Date: 3rd September 2020 AQW 6772/16-21 Revised response DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers -

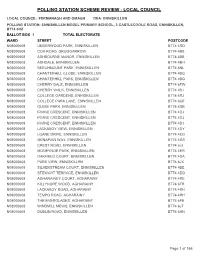

Polling Station Scheme Review - Local Council

POLLING STATION SCHEME REVIEW - LOCAL COUNCIL LOCAL COUNCIL: FERMANAGH AND OMAGH DEA: ENNISKILLEN POLLING STATION: ENNISKILLEN MODEL PRIMARY SCHOOL, 3 CASTLECOOLE ROAD, ENNISKILLEN, BT74 6HZ BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000608UNDERWOOD PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RD N08000608COA ROAD, DRUMGARROW BT74 4BS N08000608ASHBOURNE MANOR, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BB N08000608ASHDALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BH N08000608BEECHMOUNT PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6NL N08000608CHANTERHILL CLOSE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHANTERHILL PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHERRY DALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6FW N08000608CHERRY WALK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BJ N08000608COLLEGE GARDENS, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RJ N08000608COLLEGE PARK LANE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6GF N08000608GLEBE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DB N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608LACKABOY VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DY N08000608LOANE DRIVE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608MENAPIAN WAY, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4GS N08000608CREST ROAD, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JJ N08000608MONEYNOE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4ER N08000608OAKFIELD COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DA N08000608PARK VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JX N08000608SILVERSTREAM COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BE N08000608STEWART TERRACE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608AGHARAINEY COURT, AGHARAINY BT74 4RE N08000608KILLYNURE WOOD, AGHARAINY BT74 6FR N08000608LACKABOY ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608TEMPO ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608THE EVERGLADES, AGHARAINY BT74 6FE N08000608WINDMILL -

Fisheries Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2014

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY RULES OF NORTHERN IRELAND 2014 No. 17 FISHERIES Fisheries Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2014 Made - - - - 21st January 2014 Coming into operation 1st March 2014 The Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (1), makes the following Regulations in exercise of the powers conferred by sections 26(1), 37, 51(2), 52(2), 71(2)(g), 72(1), 89, 95, 114(1)(b) and 115(1) (b) (2) of the Fisheries Act (Northern Ireland) 1966 (3) and now vested in it (4). PART 1 INTRODUCTORY Citation and commencement 1. These Regulations may be cited as the Fisheries Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2014 and come into operation on 1st March 2014. Interpretation 2. (1) In these Regulations— “the Act” means the Fisheries Act (Northern Ireland) 1966; “angling” means the fishing for, taking or killing of fish by rod and line or hand line; “bait net” means a net with a single wall of netting loosely hung on ground and head ropes with the outer ends or wings leading to a bag or tail into which the catch is drafted or hauled and used for the purpose of taking coarse fish for use as bait; “barbless hook” means a hook from which the barb or barbs have been removed or bent closed or which is manufactured without a barb; “braided” in relation to a net making material means the interlocking of three or more multifilament yarns so as to form a net making material; (1) Established by the Departments (Northern Ireland) Order 1999 (S.I. -

The Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster : The Story of Co. Fermanagh Fermanagh County Museum Enniskillen Castle Castle Barracks Enniskillen Co. Fermanagh A Teachers Aid produced by N. Ireland BT74 7HL Fermanagh County Museum Education Service. Tel: + 44 (0) 28 6632 5000 Fax: +44 (0) 28 6632 7342 Email: [email protected] Web:www.enniskillencastle.co.uk Suitable for Key Stage 3 Page 1 The Plantation Medieval History The Anglo-Normans conquered Ireland in the late 12th century and by 1250 controlled three-quarters of the country including all the towns. Despite strenuous efforts, they failed to conquer the north west of Ireland and this part of Ireland remained in Irish hands until the end of the 16th century. The O’Neills and O’Donnells controlled Tyrone and Donegal and, from about 1300, the Maguires became the dominant clan in an area similar to the Crowning of a Maguire Chieftain at Cornashee, near Lisnaskea. Conjectural drawing by D Warner. Copyright of Fermanagh County Museum. present county of Fermanagh. In the rest of the country Anglo Norman influence had declined considerably by the 15th century, their control at that time extending only to the walled towns and to a small area around Dublin, known as the Pale. However, from the middle of the 16th century England gradually extended its control over the country until the only remaining Gaelic stronghold was in the central and western parts of the Province of Ulster. Gaelic Society Gaelic Ireland was a patchwork of independent kingdoms, each ruled by a chieftain and bound by a common set of social, religious and legal traditions. -

Enniskillen, Nov 6Th 1834 Dear Sir. I Send You the Name Books Of

Enniskillen, Nov 6th 1834 River (ABHAINN NA SAILISE) he slipped on its slippery banks and the books fell off his horns and it was sometime before he could fix them up again. This Dear Sir. was affected by the genius or sheaver (shaver) who presided over the Sillees, I send you the name books of Templecarn, Devenish, Enniskillen, ' who did all in his power to prevent the establishment of the christian religion in Derryvullan, Boho and Inishmacsaint. I expect that Mr. Sharkey will have the that neighbourhood. As soon as Faber had understood that the demon of the usual watch on me. It is very difficult to adhere to the analogies of Derry and river thus annoyed the good beast, she cursed the river praying that the Sillees Down in the names of this county, because the pronunciation is nearly might be cursed with sterility of fish and fertility in the destruction of human Connaught. The termination reagh, I was obliged to make reevagh in some life, and that it might run against the hill. The curse was pronounced in the instances, and garve, I had to make garrow. The word TAOBH, i.e. side or brae- following Irish words:- face frequently enters into the names here; this we have anglicized Tieve in MI-ADH EISC A'S ADH BAIDHTE Derry, Down & Antrim. I have used the same spelling of it here, but I am afraid it is too violent as every authority makes it Teev. The more northerly AG RITH ANAGHAIDH AN AIRD GO LA BRATHA. pronunciation is tee-oov, the Fermanagh one Teev. -

PO Minister's Letter

AQW 6772/16-21 Annex A DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers DfI Ballinamallard Yard Owned 4,200m2 Riversdale Fermanagh BT94 2NA Land area 0.89 DfI Portora Sluice Enniskillen Sluice Gates Owned hectacres Rosscrennagh to Rossharbour, DfI Land Owned 0.1236 Hectares Leggs - Railway Land Rosscrennagh to Rossharbour, 0.1302 0.1833 DfI Land Owned Leggs - Railway Land Hectares Drumard/Drumhoney, Kesh - DfI Land Owned 0.6150 Hectares Railway Land Drummoyagh/Drumhoney, Kesh - DfI Land Owned 0.6385 Hectares Railway Land Drummoyagh/Drumhoney, Kesh -

Area Profile of Ballinamallard

‘The Way It Is’ Area Profiles A Comprehensive Review of Community Development and Community Relationships in County Fermanagh December 98 AREA PROFILE OF BALLINAMALLARD (Including The Townland Communities Of Whitehill, Trory, Ballycassidy, Killadeas And Kilskeery). Description of the Area Ballinamallard is a small village, approximately five miles North of Enniskillen; it is located off the main A32, Enniskillen to Irvinestown road on the B46, Enniskillen to Dromore road. Due to its close proximity to Enniskillen, many of the residents work there and Ballinamallard is now almost a ‘dormitory’ village - house prices are relatively cheaper than Enniskillen, but it is still convenient to this major settlement. With Irvinestown, located four miles to its North, the village has been ‘squeezed’ by two economically stronger settlements. STATISTICAL SUMMARY: BALLINAMALLARD AREA (SUB-AREAS: WHITEHILL, TRORY, BALLYCASSIDY, KILLADEAS) POPULATION: Total 2439 Male 1260 (51.7%) Female 1179 (48.3%) POPULATION CHANGE 1971-1991: 1971 1991 GROWTH 2396 2439 1.8% HOUSEHOLDS: 794 OCCUPANCY DENSITY: 3.07 Persons per House. DEPRIVATION: OVERALL WARD: Not Deprived (367th in Northern Ireland) Fourth Most Prosperous in Fermanagh ENUMERATION DISTRICTS: NINE IN TOTAL Four Are Deprived One In The Worst 20% in Northern Ireland UNEMPLOYMENT (September 1998): MALES 35 FEMALES 18 OVERALL 53 RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION: CATHOLIC: 15.7% PROTESTANT: 68.2% OTHERS / NO RESPONSE: 16.1% Socio-Economic Background: The following paragraphs provide a review of the demographic, social and economic statistics relating to Ballinamallard village and the surrounding townland communities of Whitehill, Trory, Ballycassidy and Killadeas. According to the 1991 Census, 2439 persons resided in the Ballinamallard ward, comprising 1260 males and 1179 females; the population represents 4.5% of Fermanagh’s population and 0.15% of that of Northern Ireland. -

62953 Erne Waterway Chart

waterways chart_lower 30/3/04 3:26 pm Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 132 45678 GOLDEN RULES Lakeland Marine VORSICHT DRUMRUSH LODGE FOR CRUISING ON THE ERNE WATERWAY Niedrige Brücke. Durchfahrtshöhe 2.5M Use only long jetty H Teig Nur für kleine Boote MUCKROSS on west side of bay DANGER The Erne Waterway is not difficult to navigate, but there are some Golden Rules which MUST e’s R Harbour is too BE OBEYED AT ALL TIMES IF YOU ARE NOT TO RUN AGROUND or get into other trouble. Long Rock CAUTION shallow for cruisers Smith’s Rock ock Low bridge H.R 2.5m Fussweg H T KESH It must be appreciated that the Erne is a natural waterway and not dredged deep to the sides Small boats only Macart Is. Public footpath LOWER LOUGH ERNE like canal systems. In fact, the banks of the rivers and the shores of all the islands are normally P VERY SHALLOW a good way from the shore line and are quite often rocky! Bog Bay Fod Is. 350 H Rush Is. A47 Estea Island Pt. T Golden Rule No 1: NEVER CRUISE CLOSE TO THE SHORE (unless it is marked on the map Hare Island ross 5 LUSTY MORE uck that there is a good natural bank mooring). Keep more or less MID-STREAM wherever there A M Kesh River A 01234 Grebe WHITE CAIRN 8M are no markers, and give islands a very wide berth, at least 50-100 metres, unless there is a Black Bay BOA ISLAND 63C CAUTION Km x River mouth liable jetty on the island. -

200 Years of Worship at St. Mark's, Aghadrumsee

Member of the worldwide Anglican Communion May 2019 £1.50/€1.65 200 YEARS OF WORSHIP AT ST. MARK’S, AGHADRUMSEE Also Inside,,, Bishop announces Diocesan appointments - Pages 64 & 65 Check out our website www.clogher.anglican.org ARMSTRONG Funeral Directors & Memorials Grave Plot Services • A dignified and personal 24hr service • Offering a caring and professional service Specialists In Quality Grave Care • Memorials supplied and erected • Large selection of headstones, vases open books • Cleaning of Headstones & Surrounds • Resetting Fallen or Leaning Headstones or Damaged Surrounds • Open books & chipping’s • Reconstruction of Sunken or Raised Graves • Also cleaning and renovations • Supply & Erection of Memorial Headstones & Grave Surrounds to existing memorials • Additional Inscriptions & Repairs to Lettering • Additional lettering • New Marble or Granite Chips in your Chosen Colour • Marble or Granite Chips Washed & Restored • Regular Maintenance Visits eg : Weekly, Monthly, or Special Dates Dromore Tel. • Floral Tributes(Anniversary or Special Dates) 028 8289 8424 Contractors to The Commonwealth Omagh Tel. 028 8224 0803 War Graves Commission Robert Mob. 077 9870 0793 A Quality Professional & Personal Service Derek Mob. www.graveimage.co.uk • [email protected] 079 0027 8633 Contact : Stuart Brooker Tel: 028 6634 1611 Mob: 07968 738 491 35 Kildrum Rd, Dromore, Cullen, Monea, Enniskillen BT93 7BR Co. Tyrone, BT78 3AS EMMA McADOO MCFHP MAFHP MNRRI Chiropody Treatments - General & Diabetic Footcare Attending Ballybay Pharmacy every 2nd Thursday • Home Clinic & Visiting Practice • Custom Made Orthotics Mobile: 086 1901247 Killygraggy, Aghabog, Co. Monaghan IAN MCELROY JOINERY For all your joinery, carpentry, roofing and tiling needs Tel: 02866385226 or 07811397429 Wrought Iron Gates, Railings & Victorian Style Outdoor Lighting Kenneth Hall 43 Abbey Road Lisnaskea Co.