Gambling Public Funds on a New Vikings Stadium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dallas Sidekicks 1984- 85 Numerical Roster NO

Ooo-la-la! 1984-85 MEDIA GUIDE Oom-pah-pah. • TABLE OF CONTENTS Starting April 11, 1985, Directory 2 American Airlines, the official airline Management 3-6 Staff 7 of the Dallas Sidekicks, will offer History 8 new nonstop service from Dallas/ Coach 9 Fort Worth to both Frankfurt and Players 10-19 Paris. That's in addition to daily Position Chart 14 Pronunciation Guide 1 4 nonstops to London from Dallas/ Television Schedule 1 9 Fort Worth. Ticket Information 20 What's more, once you get to 1984-85 Rosters 22-23 Europe, you can take advantage of Franchise Top Crowds 24 Top 20 Crowds 24 connections to other major cities in Eastern Division 26 Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Western Division 27 So check out American's non- How Game is Played 28-29 stop service to London, Paris and MISL Condensed Laws 30-31 MISL Regulations 32-33 Frankfurt. And find out what all the MISL Playoff 84 34-35 hoopla is about. MISL Playoff 85 34 1 983-84 Final Standings 36 1 983-84 Scoring Leaders 37 AmericanAirlines 1 983-84 Top Goalkeepers 38-39 Something special in the air" MISL All Time Leaders 40-41 MISL Records - Regular Season 42-45 MISL Records - Playoffs 46-49 1 984-85 Schedule 50-54 MISL Award Winners 55 Edited by Pat Wallace Editorial Assistance by Bill Pou and Tim Healy Photography by Layne Murdoch and Phil Stephens Designed by Ray Shafer of Williamson Printing Corp. Cover Art by Bill Winn 1 Donald J. Carter President Donald J. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2019 Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities: Applying the Ideal-Type to the Facilities of the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association Benjamin Downs Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Other Kinesiology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Downs, Benjamin, "Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities: Applying the Ideal-Type to the Facilities of the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4989. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4989 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. EXAMINING THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN MULTIPURPOSE FACILITIES: APPLYING THE IDEAL-TYPE TO THE FACILITIES OF THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE AND NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Kinesiology by Benjamin Downs B.A., The College of Wooster, 2008 M.S., Mississippi State University, 2016 August 2019 This dissertation is dedicated to my daughter Stella Corinne. Thank you for being my source of inspiration and provider of levity throughout this process. I love you Birdie. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. -

The Broward County Civic Arena: 2 History, Facts and Opportunities

Contributors Purvi Bhogaita, Director of Real Property Public Works Department Leah Brasso, Assistant to the Department Director Finance and Administrative Services Monica Cepero, Assistant County Administrator County Administration Marcie Gelman, Assistant Budget Director Office of Management and Budget Services Roberto Hernandez, Deputy County Administrator County Administration Carol Hudson, Vice President, Sports Development Greater Fort Lauderdale Visitors & Convention Bureau Izadora Isidore-Thomas, Graduate Intern Office of the County Administrator Scott Miller, Chief Financial Officer Finance and Administrative Services Bob Miracle, Deputy Chief Financial Officer Finance and Administrative Services Noel Pfeffer, Deputy County Attorney Office of the County Attorney Henry Sniezek, Director of Planning and Redevelopment Environmental Protection and Growth Management Department We also appreciate assistance provided by the County Attorney’s Office, the County Auditor’s Office, and the Office of Public Communications. The Broward County Civic Arena: 2 History, Facts and Opportunities EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In September 2013, the Florida Panthers hockey team was sold for the fourth time in its twenty-year history. The new owners, assumed responsibility for the team’s parent company – Sunrise Sports & Entertainment and several of its subsidiaries, including, the Arena Operating Company (AOC), the Arena Development Company (ADC) and the Florida Panthers Hockey Club. Immediately upon the sale, SSE approached Broward County with a request to -

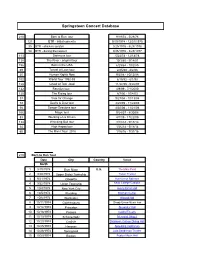

Springsteen Concert Database

Springsteen Concert Database 210 Born to Run tour 9/19/74 - 5/28/76 121 BTR - initial concerts 9/19/1974 - 12/31/1975 35 BTR - chicken scratch 3/25/1976 - 5/28/1976 54 BTR - during the lawsuit 9/26/1976 - 3/25/1977 113 Darkness tour 5/23/78 - 12/18/78 138 The River - original tour 10/3/80 - 9/14/81 156 Born in the USA 6/29/84 - 10/2/85 69 Tunnel of Love tour 2/25/88 - 8/2/88 20 Human Rights Now 9/2/88 - 10/15/88 102 World Tour 1992-93 6/15/92 - 6/1/93 128 Ghost of Tom Joad 11/22/95 - 5/26/97 132 Reunion tour 4/9/99 - 7/1/2000 120 The Rising tour 8/7/00 - 10/4/03 37 Vote for Change 9/27/04 - 10/13/04 72 Devils & Dust tour 4/25/05 - 11/22/05 56 Seeger Sessions tour 4/30/06 - 11/21/06 106 Magic tour 9/24/07 - 8/30/08 83 Working on a Dream 4/1/09 - 11/22/09 134 Wrecking Ball tour 3/18/12 - 9/18/13 34 High Hopes tour 1/26/14 - 5/18/14 65 The River Tour 2016 1/16/16 - 7/31/16 210 Born to Run Tour Date City Country Venue North America 1 9/19/1974 Bryn Mawr U.S. The Main Point 2 9/20/1974 Upper Darby Township Tower Theater 3 9/21/1974 Oneonta Hunt Union Ballroom 4 9/22/1974 Union Township Kean College Campus Grounds 5 10/4/1974 New York City Avery Fisher Hall 6 10/5/1974 Reading Bollman Center 7 10/6/1974 Worcester Atwood Hall 8 10/11/1974 Gaithersburg Shady Grove Music Fair 9 10/12/1974 Princeton Alexander Hall 10 10/18/1974 Passaic Capitol Theatre 11 10/19/1974 Schenectady Memorial Chapel 12 10/20/1974 Carlisle Dickinson College Dining Hall 13 10/25/1974 Hanover Spaulding Auditorium 14 10/26/1974 Springfield Julia Sanderson Theater 15 10/29/1974 Boston Boston Music Hall 16 11/1/1974 Upper Darby Tower Theater 17 11/2/1974 18 11/6/1974 Austin Armadillo World Headquarters 19 11/7/1974 20 11/8/1974 Corpus Christi Ritz Music Hall 21 11/9/1974 Houston Houston Music Hall 22 11/15/1974 Easton Kirby Field House 23 11/16/1974 Washington, D.C. -

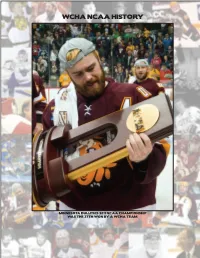

Section 5- 2020-21 WCHA NCAA History.Indd

WCHA NCAA HISTORY WESTERN COLLEGIATE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION (1951-2021) WCHA NCAA HISTORY MINNESOTA DULUTH’S 2011 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIP WAS THE 37TH WON BY A WCHA TEAM. 135 WESTERN COLLEGIATE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION (1951-2021) WCHA NCAA HISTORY WCHA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS 1952 • MICHIGAN 1953 • MICHIGAN 1955 • MICHIGAN Back Row (L-R): Eddie May, Joe Marmo, Head Coach Back Row (L-R): Curtis Swelt, Bill Lucier, Trainer Carl Back Row (L-R): Head Coach Vic Heyliger, Bill Lucier, Neil Vic Heyliger, Trainer Carl Isaacson, Bob Heathcott, Alex Isaacson, Lou Paolatto, Alex MacLellan, Doug Philpott, Buchanan, Bernie Hanna, Baden Cosby, Bob Pitts, Lorne MacLellan, Graham Cragg, Pat Cooney, Paul Pelow, Reggie Reggie Shave, Burt Dunn, Doug Mullen, Telly Mascarin, Pat Howes, Jay Gould, Gerald Karpinka, Trainer Carl Isaacson. Shave, Doug Philpott, Doug Mullen, Manager Chuck Hyman. Cooney, Jim Hass, Head Coach Vic Heyliger. Front Row (L-R): Mike Buchanan, Bob Schiller, Bill Front Row (L-R): John McKennell, Earl Keyes, Tournament Front Row (L-R): Manager Albert Picus, George Chin, Ron MacFarland, Tom Rendall, Yves Hebert, Dick Dunnigan. Queen Leslie Lockhart, Ron Martinson, George Chin, Willard Martinson, Tournament Queen Mary Ann Harman, John Ikola, Jim Haas. Matchefts, Willard Ikola. Overall Record: 18-5-1 WIHL: 13-5-0 – Second Overall Record: 22-4-0 Overall Record: 17-7-0 Head Coach: Vic Heyliger MCHL: 9-3-0 – Tie-Second MCHL: 12-4-0 – Tie-First Captain: Bill MacFarland Head Coach: Vic Heyliger Head Coach: Vic Heyliger Captain: Earl Keyes Captain: John Matchefts Dec. 4 McGill W 7-2 Dec. 5 McGill W 4-2 Dec. -

Minnesota Stadium and Arena History

Minnesota Stadium and Arena History Timberwolves/ Twins/ Vikings/ Minnesota Wild/ Gophers/ Twins/ Target Center Metrodome Metrodome Excel Center TCF Bank Stadium Target Field Current facility, date of NBA Timberwolves at MLB AL Minnesota Twins NFL Minnesota Vikings NHL Minnesota Wild at Gophers Football Stadium, Target Twins Baseball substantial completion Target Center, 1990 at the HHH Metrodome, and University of Xcel Energy Center, 1998 2009 Stadium, 2010 1982 Minnesota Gophers at the HHH Metrodome, 1982 City Minneapolis Minneapolis St. Paul Minneapolis Minneapolis Original state or regional --- Met Council revenue bonds; retired State general fund $10.25 million per year, for $392 million, revenue contribution to financing; appropriation of $65 25 years; total of $256.25 bonds sold by Hennepin later state or regional $55 million, excluding infrastructure, or $124 million, million ($48 million must million County contribution with infrastructure be repaid to state, without interest, beginning in 2003 $288 million is total cost in $522 million total cost and according to the 2008 schedule in law) Bonds sold by University $130 million-$150 million of Minnesota Original local financing Minneapolis, subsidies of 1977-1979: metrowide hospitality tax; St. Paul, $65 million from University of Minnesota, 0.15 percent sales tax in about $23 million 1979-1984: Minneapolis hospitality sales tax to provide sales tax revenue bonding $111 million Hennepin County enough for debt service Original team/league $104 million, built by --- --- $45 million -

!- Bilk Itiso.Feyb

III sot»O OVER 400,000 fans have already seen TED NUGENT in concert this year... and that's only the beginning! RECENT CONCERTS UPCOMING CONCERTS 3/7- CAPITOL CENTER, WASHINGTON D.C. 3/8 THE 5/19- WING'S STAD' UM, KALAMAZOO, MI.5/20- SPECTRUM, PHILADELPHIA, PA 3/9 THE CAPITOL WENDLER ARENA, SAGINAW, MI 5/23-RICHFIELD THEATRE, WILLIAMSPORT, PA 3 /11- CENTRUM, COLISEUM, CLEVELAND, OH 5 /24- RIVERBEND WORCESTER, MA 3 /12- MIDHUDSON CIVIC CENTER, MUSIC CENTER, CINCINNATI, OH 5/26 -FAIR POUGHKEEPSIE, NY 3/13 THE PALACE, ALBANY, GROUNDS, DES MO NES, IA 5/27 -KIEL NY 3/14-CIVIC CENTER, SALISBURY, MD 3/15- AUDITORIUM, ST. LOUIS, MO 6/1- MESKER COLISEUM, NEW HAVEN, CT. 3/16 -CIVIC CENTER, AUDITORIUM, EVANSVILLE, IN 6/4 -CIVIC CENTER, SPRINGFIELD, IL 3/18 -CIVIC CENTER, PROVIDENCE, CHARLESTON, WV 6/5 -CIVIC CENTER, ROANOKE, VA RI.3/19 -WAR MEMORIAL, SYRACUSE, NY 3/20 - 6/8- COLISEUM, COLUMBIA, SC- 6 /10- JEFFERSON PITTSBURGH CIVIC CENTER, PITTSBURGH, PA 3/22 - CIVIC CENTER, BIRMINGHAM, AL 6/11 -VON BRAUN SCOPE, NORFOLK, VA 3 /23- RICHMOND COLISEUM, CIVIC CENTER, HUNTSVILLE, AL 6/13- MISSISSIPPI RICHMOND, VA 3/25 -OMNI, ATLANTA, GA 3/28 - COAST COLISEUM, BILOXI, MS 6/21- MID -SOUTH SPORTATORIUM, MIAMI, FL 3/29 -LEE CIVIC CENTER, CIVIC CENTER, MEMPHIS, TN 7 /9- CAPITOL CENTER, FT. MYERS, FL 3/30-VETERAN'S MEMORIAL WASHINGTON D.C. 7/10- HAMPTON RHODES COLISEUM, JACKSONVILLE, FL 4 /1- MEMORIAL COLISEUM, HAMPTON, VA 7/13 -CIVIC CENTER. AUDITORIUM, NASHVILLE, TN 4/2 -C VIC COLISEUM, AUGUSTA, GA 7 /15- CONVENTION CENTER, KNOXVILLE, TN 4 /4- COLISEUM, CHARLOTTE, NC NIAGARA, NY 7/16 TORONTO, CANADA 7/18 - 4 /5- FREEDOM HALL, JOHNSON CITY, TN 4/8- SPECTRUM, PHILADELPHIA, PA 7/19- COLISEUM, MADISON SQUARE GARDEN, NEW YORK, NY 4/10 - NASSAU, NY 7/21 -WAR MEMORIAL ARENA, HERSHEYPARK ARENA, HERSHEY, PA 4/11 - JOHNSTON, PA 7/22 -CIVIC CENTER, WHEELING, SHEA'S BUFFALO THEATER, BUFFALO, NY 4/12 - WV 7 /24- CAYUGE FAIRGROUNDS, WEEDSPORT, NY - MEADOWLAND'S ARENA, E. -

NHL ARENA HISTORY (1917-Present)

NHL ARENA HISTORY (1917-Present): TEAM YEARS ARENA CURRENT USE Atlanta 1999-Present Philips Arena Current Arena Thrashers Boston Bruins 1995-Present Fleet Center Current Arena 1928-1995 Boston Garden Demolished in 1998; 1924-1928 Boston Arena Renamed to Matthews Arena and home of Northeastern University athletics. Buffalo Sabres 1996-Present Marine Midland Arena Current Arena 1970-1996 Memorial Auditorium Vacant: Proposed uses for the old Memorial Auditorium include, a family entertainment complex, a future home for Empire Sports Network, a sports bar, and a practice space for the Buffalo Sabres. Calgary Flames 1983-Present Olympic Saddledome Current Arena 1980-1983 Calgary Corral Atlanta Flames 1972-1980 The Omni Demolished in 1997; New Philips Arena built on site. Carolina 1999-Present Raleigh Entertainment Current Arena Hurricanes and Sports Arena 1997-1999 Greensboro Coliseum Hartford Whalers 1980-1997 Hartford Civic Center II Now home to a variety of athletic events including minor league hockey, arena football, NCAA basketball and other social and civic events. 1979-1980 Springfield Civic Center Home of AHL’s Springfield Falcons (Springfield MA) Chicago 1994-Present United Center Current Arena Blackhawks 1929-1994 Chicago Stadium Demolished in 1994; Now used for parking for the United Center 1926-1929 Chicago Coliseum Colorado 1999-Present Pepsi Center Current Arena Avalanche 1995-1999 McNichols Sports Arena Demolished in 2000; Quebec Nordiques 1979-1995 Le Colisse de Quebec Still standing; Possible AHL team in the future. Dallas -

2020 Nhl Draft Presented by Ea Sports Nhl 21 Information Guide

2020 NHL DRAFT PRESENTED BY EA SPORTS NHL 21 INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020 NHL Draft Order of Selection............................................................................................................................... 3 2020 NHL Draft Picks by Team.................................................................................................................................... 7 Summary of Traded 2020 NHL Draft Picks ................................................................................................................... 8 Draft Order Procedure for 2020 NHL Draft.................................................................................................................. 14 2020 NHL Draft Lottery Results ................................................................................................................................. 15 All-Time NHL Draft Lottery Results ............................................................................................................................ 16 2020 NHL Draft Quick Hits ........................................................................................................................................ 17 Notable Team Picks in 2020 Round 1 Draft Slot(s)...................................................................................................... 21 NHL Central Scouting Final Rankings for 2020 NHL Draft North American Skaters ............................................................................................................................... -

Twins Stadium Financing

AUGUST13,1997VOLUME12,NO.I X Money Matters A Publication of the Minnesota House Fiscal Analysis Department on Government Finance Issues Twins Stadium Financing Abstract: This article examines the cost of the proposed new stadium for the Minnesota Twins Major League Baseball franchise and possible sources of financing for the new stadium. The Twins’ estimate of the cost of the new stadium, including land acquisition and one-time costs associated with debt financing, is $506.1 million. If $431.1 million of that cost were financed through the issuance of 30-year taxable bonds bearing 7.5 percent interest, the annual debt service obligation would be $36.5 million. Increasing “up front” funding or decreasing the cost of the stadium would decrease the annual debt service obligation. Possible sources of revenues to fund the annual debt service obligation include revenues that the team owners would receive from the new stadium, a ticket surcharge, lottery proceeds, new taxes, and net revenues from casino gaming. Introduction The Minnesota Twins Major League Baseball franchise moved from Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington to the Metrodome in downtown Minneapolis for the start of the 1982 baseball season. The Metrodome, like the now- demolished Metropolitan Stadium and the Met Center hockey arena, is owned by the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission, a statutorily-created public organization. In addition to the Twins, the Minnesota Vikings National Football League (“NFL”) franchise and the University of Minnesota also have leases for the Metrodome. The Twins franchise now is owned by the Pohlad family. The Pohlads claim that they have been subsidizing the Twins’ operating losses over the last several seasons. -

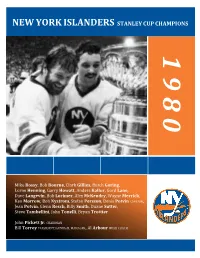

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

NEW YORK ISLANDERS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 8 0 Mike Bossy, Bob Bourne, Clark Gillies, Butch Goring, Lorne Henning, Garry Howatt, Anders Kallur, Gord Lane, Dave Langevin, Bob Lorimer, Alex McKendry, Wayne Merrick, Ken Morrow, Bob Nystrom, Stefan Persson, Denis Potvin CAPTAIN, Jean Potvin, Glenn Resch, Billy Smith, Duane Sutter, Steve Tambellini, John Tonelli, Bryan Trottier John Pickett Jr. CHAIRMAN Bill Torrey PRESIDENT/GENERAL MANAGER, Al Arbour HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1980 PRELIMINARY ROUND 1 PHILADELPHIA FLYERS 116 v. 16 EDMONTON OILERS 69 GM KEITH ALLEN, HC PAT QUINN v. GM LARRY GORDON, HC GLEN SATHER FLYERS SWEEP SERIES Tuesday, April 8 Wednesday, April 9 EDMONTON 3 @ PHILADELPHIA 4 OT EDMONTON 1 @ PHILADELPHIA 5 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. PHILADELPHIA, Paul Holmgren 1 (Ken Linseman, Bob Dailey) 0:56 1. EDMONTON, Don Murdoch 2 (Kevin Lowe, Mark Messier) 1:14 2. PHILADELPHIA, Reggie Leach 1 (Bobby Clarke) 6:19 2. PHILADELPHIA, Behn Wilson 1 (Paul Holmgren, Al Hill) 13:32 3. EDMONTON, Dave Lumley 1 (Wayne Gretzky, Blair MacDonald) 14:09 PPG 4.