A Study for the Artist Through Theories of Art & Visual Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Developing a Content Pipeline for a Video Game

Antti Veräjänkorva Art Is A Mess: Developing A Content Pipeline for A Video Game. Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Master of Engineering Information Technology Master’s Thesis 7 July 2020 PREFACE I have a dream that I can export all art asset for a game with single button press. I have tried to achieve that a couple times already and never fully accomplished in this. This time I was even more committed to this goal than ever before. This time I was deter- mined to make the life of artists easier and do my very best. Priorities tend to change when a system is 70% done. Finding time to do the extra mile is difficult no matter how determined you are. Well to be brutally honest, still did not get the job 100% done, but I got closer than ever before! I am truly honoured for all the help what other technical artists and programmers gave me while writing this thesis. I especially want to thank David Rhodes, who is a long- time friend and colleague, for his endless support. Thank you Jukka Larja and Kimmo Ala-Ojala for eye opening discussions. I would also like to thank my wife and daughter for giving me the time to write this thesis. Thank you, Hami Arabestani and Ubisoft Redlynx for giving me the chance to write this thesis based on our current project. Lastly thank you Antti Laiho for supervising this thesis and your honest feedback while working on it. Espoo, 06.06.2020 Antti Veräjänkorva Abstract Author Antti Veräjänkorva Title Art is a mess: Developing A Content Pipeline for A Video Game Number of Pages 47 pages + 3 appendices Date 7 Jul 2020 Degree Master of Engineering Degree Programme Information Technology Instructor(s) Hami Arabestani, Project Manager Antti Laiho, Senior Lecturer The topic of this thesis was to research how to improve exporting process in a video game content pipeline and implement the improvements. -

Considerations for a Study of a Musical Instrumentality in the Gameplay of Video Games

Playing in 7D: Considerations for a study of a musical instrumentality in the gameplay of video games Pedro Cardoso, Miguel Carvalhais ID+, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract. The intersection between music and video games has been of increased interest in academic and in commercial grounds, with many video games classified as ‘musical’ having been released over the past years. The purpose of this paper is to explore some fundamental concerns regarding the instrumentality of video games, in the sense that the game player plays the game as a musical or sonic instrument, an act in which the game player becomes a musical performer. We define the relationship between the player and the game system (the musical instrument) to be action- based. We then propose that the seven discerned dimensions we found to govern that relationship to also be a source of instrumentality in video games. Something that not only will raise a deeper understanding of musical video games but also on how the actions of the player are actually embed in the generation and performance of music, which, in some cases, can be transposed to other interactive artefacts. In this paper we aim at setting up the grounds for discussing and further develop our studies of action in video games intersecting it with that of musical performance, an effort that asks for multidisciplinary research in musicology, sound studies and game design. Keywords: Action, Gameplay, Music, Sound, Video games. Introduction Music and games are no exception when it comes to the ubiquity of computational systems in contemporary society. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Staying Alive Fallout 76

ALL FORMATS EXCLUSIVE Staying Alive Far Cry 4’s Alex Hutchinson How the British games industry survived its on his “louder, brasher” game turbulent early years Fallout 76 Bethesda, BETA and “spectacular” bugs Issue 1 £3 wfmag.cc 01 72000 GRIS 16 7263 97 Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12issues to order * UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer In search of real criticism an games be art? Roger Ebert judge – the critic is a guide, an educator, and an argued that they couldn’t. He was interpreter. The critic makes subtext text, traces C wrong. Any narrative medium themes, and fills in white space. Put another can produce art. But I’m not sure way, the critic helps the audience find deeper we’re producing many examples that meet JESSICA PRICE meaning in a piece of art. Or: the critic teaches that definition. Let’s be honest: everyone keeps Jessica Price is a the audience the rules of the games artists play producer, writer, and talking about BioShock because it had something manager with over a so that they’re on a level ground with the artist. to say and said it with competence and style, decade of experience One only has to compare movie or TV reviews in triple-A, indie, and not because what it had to say was especially tabletop games. in any mainstream publication, in which at least profound. Had it been a movie or a book, I doubt some critical analysis beyond “is this movie it would have gotten much attention. -

On Liberty It’S Our Best Best Of

On Liberty It’s Our Best Best of... Issue Ever A guide to the city’s top Sights Entertainment Restaurants Bars Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Table of Contents Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain 02 Installation visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. 04 Game Controls Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching 08 Letter from the Editor video games. 10 Places Best Sights These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, 12 Entertainment Best Place to Chill confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking 14 Restaurants Best Burger nearby objects. 16 Bars Best Brew Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these 18 Feature Dating in the City symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these 20 Technology Top Gadgets seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well- 22 Credits lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. 32 Warranty If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. -

The Con Psp Iso

The con psp iso click here to download Fight for the win or throw the fight to make some extra cash in this PSP fighting game. Download page for Con, The (USA). Fight for the win or throw the fight to make some extra cash in this PSP fighting game. Con, The (Europe). FILESIZE. VOTES. RATING. DownloadRATE. MBRATE. / Direct Download. ALTERNATIVE DOWNLOAD LINK: Con, The (Europe). PlayStation One (PSX) · PlayStation Portable (PSP) · Raine · Sega CD · Sega Dreamcast · Sega Master System · Sega Genesis 32X · Super Nintendo (SNES) · Turbo Grafx 16 · Wonderswan · Links · # A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z · Most Votes · Highest Rated · Most Popular. Con, The. FILESIZE. The Con (USA) PSP ISO Download for the Sony PlayStation Portable/PSP. Game description, information and PSP/PPSSPP download www.doorway.rued Size: MB. ISO download page for the game: The Con (PSP) - File: www.doorway.rut - www.doorway.ru Download Con, The (I)(BAHAMUT) ROM / ISO for PSP from Rom Hustler. % Fast Download. Game Title: The Con Publisher: Sony Computer Entertainment, Ertain Developer: Think and Feel Inc., SCEA Genre: Fighting Image Format: File Size: MB How to play? Download and Install PPSSPP emulator on your device and download The Con ISO rom, run the emulator and select your ISO. Play and enjoy the. Related Games. Forgotten Worlds (CPS1) · Patapon 2 PSP ISO · Shrek The Third PSP ISO · Petz My Baby Hamsterz PSP ISO · Petz Hamsterz Bunch PSP ISO · Petz PSP ISO · Strikers Plus PSP ISO · Up (PSP) · Tokobot PSP ISO. -

Demon's Souls Free Download Pc Demon’S Souls PC Download Free

demon's souls free download pc Demon’s Souls PC Download Free. Demon’s Souls Pc Download – Everything you need to know. Demon’s Souls is a best action role-playing game that is created by Fromsoftware that is available for the PlayStation 3. This particular game is published by Sony computer Entertainment by February 2009. It is associated with little bit complicated gameplay where players has to make the control five different worlds from hub that is well known as Nexus. It is little bit complicated game where you will have to create genuine strategies. It is your responsibility to consider right platform where you can easily get Demon’s Souls Pc Download. You will able to make the access of both modes like single player and multiplayer. It is classic video game where you will have to create powerful character that will enable you to win the game. All you need to perform the role of adventurer. In the forthcoming pargraphs, we are going to discuss important information regarding Demon’s Souls. Demon’s Souls Download – Important things to know. If you want to get Demon’s Souls Download then user should find out right service provider that will able to offer the game with genuine features. In order to win such complicated game then a person should pay close attention on following important things. Gameplay. Demon’s Souls is one of the most complicated game where you will have to explore cursed land of Boletaria. In order to choose a player then a person should pay close attention on the character class. -

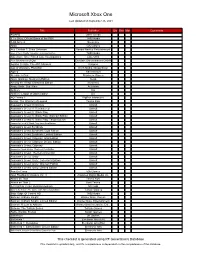

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

2019 Annual Report

TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL INC. 2019 SOFTWARE, INTERACTIVE TAKE-TWO TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Generated significant cash flow and ended the fiscal year with $1.57$1.57 BILLIONBILLION in cash and short-term investments Delivered total Net Bookings of Net Bookings from recurrent $2.93$2.93 BILLIONBILLION consumer spending grew 47% year-over-year increase 20%20% to a new record and accounted for units sold-in 39% 2424 MILLIONMILLIONto date 39% of total Net Bookings Tied with Grand Theft Auto V as the highest-rated game on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One with 97 Metacritic score One of the most critically-acclaimed and commercially successful video games of all time with nearly units sold-in 110110 MILLIONMILLIONto date Digitally-delivered Net Bookings grew Employees working in game development and 19 studios 33%33% 3,4003,400 around the world and accounted for Sold-in over 9 million units and expect lifetime Net Bookings 62%62% to be the highest ever for a 2K sports title of total Net Bookings TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, Fiscal 2019 was a stellar year for Take-Two, highlighted by record Net Bookings, which exceeded our outlook at the start of the year, driven by the record-breaking launch of Red Dead Redemption 2, the outstanding performance of NBA 2K, and better-than- expected results from Grand Theft Auto Online and Grand Theft Auto V. Net revenue grew 49% to $2.7 billion, Net Bookings grew 47% to $2.9 billion, and we generated significant earnings growth. -

Bioshock® Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two Available for Download Starting Today

BioShock® Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two Available for Download Starting Today March 25, 2014 8:00 AM ET Irrational Games delivers its final episode and concludes the story of BioShock Infinite and Burial at Sea NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Mar. 25, 2014-- 2K and Irrational Games announced today that BioShock® Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two is downloadable* in all available territories** on the PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft and Windows PC starting today. BioShock Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two, developed from the ground up by Irrational Games, is the final content pack for the award-winning BioShock Infinite, and features Elizabeth in a film noir-style story that provides players with a different perspective on the BioShock universe. “I think the work the team did on this final chapter speaks for itself,” said Ken Levine, creative director of Irrational Games. “We built something that is larger in scope and length, and at the same time put the player in Elizabeth’s shoes. This required overhauling the experience to make the player see the world and approach problems as Elizabeth would: leveraging stealth, mechanical insight, new weapons and tactics. The inclusion of a separate 1998 Mode demands the player complete the experience without any lethal action. BioShock fans are going to plotz.” *BioShock Infinite is not included in this add-on content, but is required to play all of the included content. **BioShock Infinite: Burial at Sea – Episode Two will be available in Japan later this year. About BioShock Infinite From the creators of the highest-rated first-person shooter of all time***, BioShock, BioShock Infinite puts players in the shoes of U.S.