The Synagogues of Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deportation of the Jews of Rhodes & Cos: 1944-2014 A

Περιφέρεια Νοτίου Αιγαίου Τµήµα Πολιτισµού Περιφέρειας The Deportation of the Jews of Rhodes & Cos: 1944-2014 A Commemorative International Symposium on the Holocaust in the Aegean H Απέλαση των Εβραίων της Ρόδου και της Κω: 1944-2014 Ένα Διεθνές Συμπόσιο Μνήμης για το Ολοκαύτωμα στο Αιγαίο Rhodes 22-24 July 2014 The symposium is a joint-endeavour between the Department of History, University of Limerick Ireland, the Department of Mediterranean Studies, University of the Aegean, Rhodes, General State Archives, Dodecanese, Rhodes and the Jewish Community of Rhodes. The organizers gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Danon Family (Cape Town); the Prefecture of Rhodes; Mrs Bella Angel Restis, President of the Jewish Community of Rhodes, the University of the Aegean and the Pane di Capo. The organizers: • Irene Tolios, Director of the General State Archives, Dodecanese, Rhodes • Prof. Anthony McElligott, University of Limerick, Ireland • Prof. Giannis Sakkas, University of the Aegean, Rhodes • Carmen Cohen, Administrative Director of the Jewish Community of Rhodes. Places of the Symposium: - 21-22 July: Aktaion, near Marina Mandrakiou in Rhodes (7th March str.). - 23-24 July: 7th March Building, University (Panepistimio Egeou), Dimokratias Avenue 1 (700 m. from the city centre). For the location of the places Aktaion, Marina Mandrakiou & Panepistimio Egeou see the following map of the city of Rhodes: http://www.mappery.com/map-of/Rhodes-City-Map Romios Restaurant (Monday evening): https://www.google.gr/maps/place/Romios+Restaurant/@36.442262,28.227781,17z/ -

International Conference “Jewish Heritage in Slovenia”

H-Announce International Conference “Jewish Heritage in Slovenia” Announcement published by Vladimir Levin on Wednesday, September 11, 2019 Type: Conference Date: September 18, 2019 to September 19, 2019 Location: Israel Subject Fields: Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies, Humanities, Jewish History / Studies, Local History, Art, Art History & Visual Studies The Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem University of Maribor International Conference “Jewish Heritage in Slovenia” 18-19 September 2019 Room 2001, Rabin Building, Mt. Scopus Campus, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 18 September, Wednesday 9:30 – 10:00 Registration 10:00 – 10:30 Greetings: Chair: Dr. Vladimir Levin, Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Prof. Michael Segal, Dean of Humanities, Hebrew University of Jerusalem H.E. Andreja Purkart Martinez, Ambassador of Slovenia in Israel H.E. Eyal Sela, Ambassador of Israel in Slovenia Prof. Barbara Murovec, University of Maribor Prof. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem 10:30 – 12:00 Jewish Heritage Research in Slovenia Chair: Prof. Haim Shaked (University of Miami) – Ruth Ellen Gruber (Jewish Heritage Europe) Tracing a Trail: Notes from the 1996 Survey of Jewish Heritage in Slovenia. – Ivan Čerešnješ (Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Citation: Vladimir Levin. International Conference “Jewish Heritage in Slovenia”. H-Announce. 09-11-2019. https://networks.h-net.org/node/73374/announcements/4650720/international-conference-%E2%80%9Cjewish-heritage-slovenia%E2%8 0%9D Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. 1 H-Announce Past Research of Slovenia’s Jewish Heritage by the Center Jewish Art. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

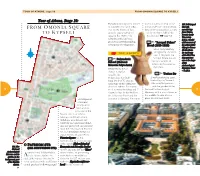

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

The Treasures of the Bezalel Narkiss Jewish Art Collection

H-Announce The Treasures of the Bezalel Narkiss Jewish Art collection Announcement published by Sara Ben-Isaac on Monday, May 3, 2021 Type: Lecture Date: May 6, 2021 Location: United Kingdom The Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was founded by Professor Bezalel Narkiss in 1979. Today, the Center's archives and collections constitute the largest and most comprehensive body of information on Jewish art in existence, with approximately 180,000 pictures, sketches and documents. Over 200,000 items have been digitized and are now freely accessible to the public. Dr Vladimir Levin has published over 120 articles and essays and has headed numerous research expeditions to document synagogues and other monuments of Jewish material culture in eastern and central Europe. He has also led several research projects in the field of Jewish Art, the most important of which is the creation of the Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art - the world’s largest digital depository of Jewish heritage. This lecture is given in memory of Thea Zucker z”l, who was a devoted supporter of the Belgian Friends through her work as a Hebrew University Governor and Honorary Fellow, and which is supported by her grandson, Marc Iarchy (London) Registration is essential. Your Zoom link will be sent a day before the lecture - please make sure it’s not in your junk mail https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/147019532379 Contact Info: Sara Ben-Isaac Contact Email: [email protected] URL: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/147019532379 Citation: Sara Ben-Isaac. The Treasures of the Bezalel Narkiss Jewish Art collection. -

Heinrich Frauberger: on the Construction and Embellishment of Old Synagogues*

Heinrich Frauberger: On the construction and embellishment of old synagogues* Summary and Analysis by Nisya Allovi, Turkish Jewish Museum Over the past few decades Jewish congregations have grown continuously in larger and medium-sized cities. Existing synagogues are not sufficient in size and extensions are in most cases impossible due to the lack of space. Due to the expansion of cities and the high price of larger sites in central locations, the building of a new, single, large synagogue is impractical; occasionally the different religious service of Orthodox Jews and liberal congregations, makes the building of two separate houses of God preferable. As a result, many new synagogues, in some towns several of them have recently been built, and every year competitions are held for the construction of new ones. As could be seen a little while ago with the competition for the building of a new synagogue in Düsseldorf, these benefit from the enthusiastic participation of architects. Unfortunately, these calls for tenders generally produce unsatisfactory results. On the one hand, the local councils are uncertain when defining requirements; on the other hand, the architects have no knowledge of how religious practice takes place and how it has evolved. They are completely unprepared for this task. In addition, it is difficult to find documentation with detailed preliminary studies. For a few years it has been possible to buy postcards of a series of new synagogues, showing both exterior and interior views. On this script he studied on 44 different images of the synagogues. With regard to technical aspects, the chapter provides some very usable suggestions and focuses on templates with regard to the decorative elements. -

2018 Annual Report 10 Association of European Jewish Museums BUDAPEST

www.aejm.org Annual Report association of european jewish museums Annual 2018 Report Table of Contents Preface 3 Activities 4 Grants 12 Cooperation 16 Communications 19 New Members 20 Board & Staff 21 Supporters 21 Committees 22 Association of European Jewish Museums Annual Report 2 association of european jewish museums AEJM Preface The Association of European Jewish Museums looks back on a successful year in which we organised five programmes at different locations across Europe. All its programmes have been awarded the official label of the European Year of Cultural Heritage. 2018 was the final year that AEJM and the Jewish Museum Berlin were able to benefit from a multiple-year grant from the German Federal Foreign Office, which allowed us to organise ten successful curatorial seminars in five years. The final editions of the Advanced Curatorial Education Pro- gramme were held in Frankfurt and Jerusalem. It is my pleasure to thank our organising team in Vienna, Dr. Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek and Dr. Michaela Feurstein-Prasser, for their enthusiasm and dedication that were key to turning our curatorial seminars into a success. We warmly thank our partners and sponsors, first and foremost the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe for its continuing support. Without the commitment of the following AEJM members as partner institutions, our activities could not have been successful: the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives in Budapest, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, and Museum “Jews in Latvia” in Riga, the Jewish Museum Frankfurt, and The Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The AEJM team was also instrumental in organising all our activities and I would like to thank our team in Amsterdam for all their efforts: Managing Director Eva Koppen, Communication Officer Robbie Schweiger, and Conference Coordinator Nikki Boot. -

Hotel Athens Imperial

2-6 M. Alexandrou, Karaiskaki str., 104 37, Athens Metro Station Metaxourgeio Tel.: +30 210 52 01 600, Fax: +30 210 52 25 524 • e-mail: [email protected] www.classicalhotels.com Classical Athens Imperial Rooms & Amenities Distinctive and welcoming, the Classical rectly to Karaiskaki Square. area in open plan style. Elegantly deco- Athens Imperial is one of the city’s most rated, and with marble bathroom with stylish and vibrant hotels. Its monumen- GUEST ROOMS & SUITES separate shower cabin and exclusive tal facade ushers guests into a tastefully The Classical Athens Imperial has a to- luxury guest amenities. All Junior Suites furnished and arty interior that combines tal of 261 rooms including 25 suites. All offer King Beds. contemporary decoration with timeless guestrooms are equipped with individu- elegance. Its state-of-art business facili- ally controlled air-conditioning, work- Corner Junior Suites: ties can transform guest rooms into an ing desk, refrigerated private maxi-bar, office and host conferences and meet- in room safe, satellite TV with 24-hour ings for up to 1,400 people, while the 7th movie channel, coffee making facilities, floor has been tailored to the needs of direct dial telephone, High-Speed Inter- discerning business executives. Over- net Access and voicemail. The marbled look the city from the roof garden, facing bathrooms accompanied by lavish vani- the Parthenon and enjoying a cocktail by ties and makeup/shaving mirror; most the pool. have separate shower cabin and feature fine personal-care items, hair dryers, slippers and terry bathrobes. Additional- Located on building’s corner on all ly, all suites and deluxe rooms on the 7th floors, and with approximately 50 square floor are equipped with iron, iron-board meters of space they consist of a spa- and coffee-machine. -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

Jewish Heritage Sites in Croatia, 2005

JEWISH HERITAGE SITES IN CROATIA PRELIMINARY REPORT United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Fayetteville, NY Staff: Michael B. Levy Jeffrey L. Farrow Washington, DC Executive Director Rachmiel Liberman Samuel D. Gruber Brookline, MA Research Director Laura Raybin Miller Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Hollywood, FL Program Manager Vincent Obsitnik Peachtree City, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: (202) 254-3824 Fax: (202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] October 10, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. The atheistic Communist Party dictatorships that succeeded the Nazis throughout most of the region were insensitive to American Jewish concerns about the preservation of the sites. -

Handbook on Judaica Provenance Research: Ceremonial Objects

Looted Art and Jewish Cultural Property Initiative Salo Baron and members of the Synagogue Council of America depositing Torah scrolls in a grave at Beth El Cemetery, Paramus, New Jersey, 13 January 1952. Photograph by Fred Stein, collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA. HANDBOOK ON JUDAICA PROVENANCE RESEARCH: CEREMONIAL OBJECTS By Julie-Marthe Cohen, Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek, and Ruth Jolanda Weinberger ©Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 2018 Table of Contents Foreword, Wesley A. Fisher page 4 Disclaimer page 7 Preface page 8 PART 1 – Historical Overview 1.1 Pre-War Judaica and Jewish Museum Collections: An Overview page 12 1.2 Nazi Agencies Engaged in the Looting of Material Culture page 16 1.3 The Looting of Judaica: Museum Collections, Community Collections, page 28 and Private Collections - An Overview 1.4 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the West: Jewish Cultural Reconstruction page 43 1.5 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the East: The Soviet Trophy Brigades and Nationalizations in the East after World War II page 61 PART 2 – Judaica Objects 2.1 On the Definition of Judaica Objects page 77 2.2 Identification of Judaica Objects page 78 2.2.1 Inscriptions page 78 2.2.1.1 Names of Individuals page 78 2.2.1.2 Names of Communities and Towns page 79 2.2.1.3 Dates page 80 2.2.1.4 Crests page 80 2.2.2 Sizes page 81 2.2.3 Materials page 81 2.2.3.1 Textiles page 81 2.2.3.2 Metal page 82 2.2.3.3 Wood page 83 2.2.3.4 Paper page 83 2.2.3.5 Other page 83 2.2.4 Styles -

5.Rhodes.Background.Proposal

1 The University of Hartford Research Group Project in Rhodes, Greece Preliminary Background Information Compiled by: Dr. Richard Freund, Maurice Greenberg Professor of Jewish History and Director, Maurice Greenberg Center for Judaic Studies, University of Hartford, Jon Gaynes and Ari Jacobson, videographers. A Short History of the Jews of Rhodes The history of the Jews of Rhodes goes back before the 2nd century BCE and is cited as a place where Jews had settled in the period of Maccabees before 172 BCE. Citing an earlier tradition, Josephus Flavius, the first century CE Jewish historian, mentions the Jews of Rhodes. One of the more significant stories about the Jews of Rhodes has to do with the Muslim conquest in the 7th century CE when the famed Colossus of Rhodes which had fallen down some 7 centuries earlier was dismantled and the Jews were assigned the task of exporting the metal covering overland to the Umayyad Syrian Caliphate. Jewish travelers in the Middle Ages mention the community. In the Crusades, the Jews of Rhodes was once again embroiled in the controversies between the Byzantine Empire and the Muslims. The Templars Knights and the Jews lived near one another in the area of the walls of the Old City of Rhodes during the Middle Ages. Later, the Jews are described as fierce defenders of the walled city (today called: Old Town) against the Turks in 1480. Under the Turkish Sultan Suleiman, the community prospered and many exiles from the 1492 expulsion from Spain came to live in Rhodes. The island was populated by ethnic groups from the surrounding nations, including Jews. -

What's Inside

JeT Hw E ish Georg i a n Volume 20, Number 5 Atlanta, Georgia J U LY-AUGUST 2008 F R E E What’s Inside Atlantan participates in groundbreaking visit to German archive s By Howard Margol group and the Glossary of ITS Terms and The Mind Behind Abbreviations created by the U.S. On May 4, I arrived in Bad Arolsen, Holocaust Memorial Museum in the Festival Germany, with great anticipation. Forty of Washington, D.C. (The latter brochure was The Atlanta Jewish Film Festival owes its us were there to research the over 55 mil- not very important for the records search success to Kenny Blank. lion records archived under the supervision but will be extremely useful later, as we By David Ryback of the International Tracing Service (ITS). examine the records we found.) These Nazi-era records had been withheld The ITS brochure included the Page 18 from public view for over 60 years. We research requirements, the history of the were the first group allowed to come there ITS, the many different types of records in and view the actual records. the archive, concentration camp maps, and What Seniors Want At our Sunday evening welcoming din- various other bits of interesting informa- Atlanta Theatre-to-Go brings high-quali- n e r, ITS Deputy Director Eric Oetiker gave tion. The alphabetical index contains over us an inkling of what was in store for us, and 17 million names, including 849 variations ty theater to senior communities and my excitement increased as he spoke. On of the surname Abramovitsch.