CECIL NGAKA' EBSWORTH Wangkumara Man of the Corner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

A Review of Lake Frome & Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991-2001

A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 s & ark W P il l d a l i f n e o i t a N South Australia A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 Strzelecki Regional Reserves Lake Frome This review has been prepared and adopted in pursuance to section 34A of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. Published by the Department for Environment and Heritage Adelaide, South Australia July 2002 © Department for Environment and Heritage ISBN: 0 7590 1038 2 Prepared by Outback Region National Parks & Wildlife SA Department for Environment and Heritage Front cover photographs: Lake Frome coastline, Lake Frome Regional Reserve, supplied by R Playfair and reproduced with permission. Montecollina Bore, Strzelecki Regional Reserve, supplied by C. Crafter and reproduced with permission. Department for Environment and Heritage TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF TABLES..................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF ACRONYMS and ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................iv FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Grs 513/11/P

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRS 513 Lodged company documents of defunct companies Series These files contain documents lodged by companies in Description accordance with the varying Companies Acts. Company files may contain some or all of the following lodged documents: Memorandum of Agreement, Articles of Association, Certificate of Incorporation, lists of shareholders, lists of directors, special resolutions ie. issues of shares, underwriting agreements and annual returns. Note: The term 'defunct' should not be understood to refer to the company. In this context it refers to the file being defunct, although given the age of the records some of the companies will have become defunct. Series date range 1844 - 1986 Agency State Records of South Australia responsible Access Open. Determination Contents 1874 – 1935 1 June 2016 GRS 513/11/P DEFUNCT COMPANIES FILES 4/1S74 The Stonyfell Olive Company Limited (Scm) \ 4/1874 The Stonyfell Olive Co. Limited (1 file) 1/1875 The East End Market Company (16cm)) 1/1S75 The East End Market Coy. Ltd. (1 file) 3/1SSO The Executor Trust & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (9cm &9cm)(2 bundles)) 10/1S7S Adelaide Underwriters Association Limited (3cm) 10/1S7S Marine Underwriters Association of South Australia Limited (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder's Wool and Produce Company Limited (Scm) 4/1SS2 Northern Territory Laud Company Limited (4cm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia (Scm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (1 file) 7/1SS2 Northern Territory Land Company (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder Smith & Co. -

FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT

Bureau Home > Australia > Queensland > Rainfall & River Conditions > River Brochures > Thomson, Barcoo and Cooper FLOOD WARNING SYSTEM for the COOPER CREEK CATCHMENT This brochure describes the flood warning system operated by the Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology for the Thomson, Barcoo Rivers and Cooper Creek. It includes reference information which will be useful for understanding Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins issued by the Bureau's Flood Warning Centre during periods of high rainfall and flooding. Contained in this document is information about: (Last updated September 2019) Flood Risk Previous Flooding Flood Forecasting Local Information Flood Warnings and Bulletins Interpreting Flood Warnings and River Height Bulletins Flood Classifications Other Links Cooper Creek at Nappa Merrie Flood Risk The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper catchment drains an area of approximately 237,000 square kilometres and is the largest river basin in Queensland. The catchment falls within the Lake Eyre basin, the largest and only co- ordinated internal drainage system in Australia with no external outlet, and which covers over 1.1 million square kilometres of central Australia. Floodwaters reach Lake Eyre after major flood events in the Cooper. The two main tributaries, the Thomson and Barcoo Rivers, merge into the Cooper Creek approximately 40 kilometres upstream of Windorah. The Thomson River and its tributaries flow in a general southerly direction and has several of the larger towns of the region including Longreach and Muttaburra along its banks. The Barcoo River flows in a general westerly direction and has major centres such as Isisford, Blackall, Barcaldine, Jericho and Tambo in its catchment. The Thomson-Barcoo-Cooper basin can be divided into two distinct areas: * Above Windorah, numerous well-defined creeks and channels flow into the Thomson and Barcoo. -

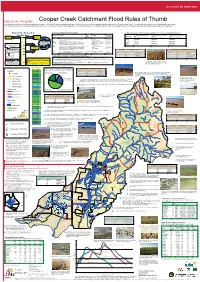

Cooper Creek Catchment Flood Rules of Thumb This Guide Has Used the Best Information Available at Present

QueenslandQueenslandthethe Smart Smart State State How to use this guide: Cooper Creek Catchment Flood Rules of Thumb This guide has used the best information available at present. It is intended to help you assess what type of flood is likely to occur in your area and indicate what amount of feed you might expect. You may wish to record your own flooding guides on the map. You can add more value to this guide by participating in an MLA EDGEnetwork Grazing Land Management (GLM) training package. GLM training helps you identify land types and flood zones and to develop a grazing management plan for your property Amount of rain needed Channel Country Flood descriptions Estimated Summer Flood Pasture Growth in the Channel Country Floodplains. Frequently flooded plains Occasionally flooded plains Swamps and depressions for flooding Flood type Description Land Hydrology Pasture growth Isolated Systems which supports: Flood type (C1) (C2) (C3) Widespread Widespread Rain 100 mm Localised Rain “HANDY” to flooded “GOOD” flood Then increases (kg DM/ha of useful feed) (kg DM/ha of useful feed) (kg DM/ha of useful feed) 95 “GOOD” flood Good Good floods are similar to handy floods, but cover a much higher C1, C3, C2 Flooded across most of 85 - 100% of to proportion of the floodplain (75% or more) and grow more feed per floodplains potential cattle Good 1200-2500 1500-3500 4500-8000 90 area than a handy flood. 80-100% inundation numbers 85 IF in 24-72 hrs Handy Handy floods occur when the water escapes from the gutters, C1, C3 Pushing out of gutters across 45 - 85% of Handy 750-1500 100-250 3500-6500 80 PRIOR, rains of (or useful) connecting up to form the large sheets of water. -

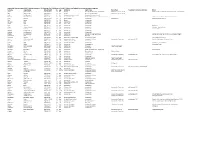

List of Deaths.Xlsx

Innamincka Records compiled 2011. Materials supplied b:- SA Genealogy Soc. D Spackman. K Buckley. Office for the Outback Community Authority, Pt Augusta. Surname Given Names Date of Death Sex Age Residence Death Place Burial Place Headstone Innamincka Cemetery Detail Burke Robert O'Hara 1861-06/07-? M 40y Victoria Near Burke Waterhole, Innamincka Melbourne General Cem Memorial Burke's Waterhole Cooper Creek Nr Innamincka Wills William John 1861-06/07-? M 27y Victoria Near Tilcha Waterhole Melbourne General Cem Colless Not Recorded 1880-08-17 F 3h Innamincka Coopers Creek Innamincka Coopers Creek Howard Henry Grenville 1881-11-01 M 50y Innamincka Station Between Mt Lyndhurst and Farina Town Cook. Injuries received thrown from his trap. Cook Richard 1883/4-12-02 M 45y Monta Collina Innamincka Patchewarra Police Mortuary Returns Tee James 1885-05-13 M 37y Farina Innamincka Richards John 1886-02-08 M 61y Innamincka Innamincka Budge John 1887-03-22 M 23y Oonta. Qld Innamincka Dick Samuel 1887-09-07 M 3w Innamincka Innamincka Bronchitis Rowe Thomas Roberts 1888-03-22 M 20y Innamincka Innamincka Labourer. Typhoid Fever. Copp Andrew 1888-05-10 M 37y Innamincka Innamincka Cancer of Throat Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 36h Innamincka Innamincka Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 24h Innamincka Innamincka Charley Not Recorded 1893-11-15 M 23y Innamincka Coopers Crk near Lake Hope Aboriginal. Drover.Verdict of Jury -no cause of death McDermott John 1891-07-12 M 36y Innamincka Adelaide Crossman William 1891-08-20 M 30y Nappa Merrie Station Qld Innamincka Station Police Mortuary Returns Bralla William Emanuel 1894-01-23 M 23y Innamincka Station Innamincka Station Innamincka Cemetery photograph 2011 Accidentally drowned Coopers Creek Hampton Edwin John 1894-12-28 M 23y Asbevale Station Qld Innamincka Smith Alick 1895-03-30 M 53y Innamincka Station Innamincka Stockman. -

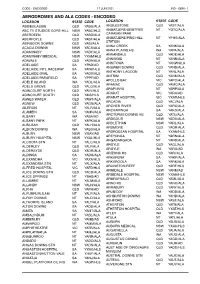

Aerodromes and Ala Codes

CODE - ENCODED 17 JUN 2021 IND - GEN - 1 AERODROMES AND ALA CODES - ENCODED LOCATION STATE CODE LOCATION STATE CODE ABBIEGLASSIE QLD YABG/ALA ANGLESTONE QLD YAST/ALA ABC TV STUDIOS GORE HILL NSW YABC/HLS ANMATJERE/GEMTREE NT YGTC/ALA ABERDEEN QLD YABD/ALA CARAVAN PARK ABERFOYLE QLD YABF/ALA ANMATJERE/PINE HILL NT YPHS/ALA STATION ABINGDON DOWNS QLD YABI/ALA ANNA CREEK SA YANK/ALA ACACIA DOWNS NSW YACS/ALA ANNA PLAINS HS WA YAPA/ALA ADAMINABY NSW YADY/ALA ANNANDALE QLD YADE/ALA ADAMINABY MEDICAL NSW YXAM/HLS ANNINGIE NT YANN/ALA ADAVALE QLD YADA/ALA ANNITOWA NT YANW/ALA ADELAIDE SA YPAD/AD ANSWER DOWNS QLD YAND/ALA ADELAIDE INTL RACEWAY SA YAIW/HLS ANTHONY LAGOON NT YANL/ALA ADELAIDE OVAL SA YAOV/HLS ANTRIM QLD YANM/ALA ADELAIDE/PARAFIELD SA YPPF/AD APOLLO BAY VIC YAPO/ALA ADELE ISLAND WA YADL/ALA ARAMAC QLD YAMC/ALA ADELS GROVE QLD YALG/ALA ARAPUNYA NT YARP/ALA AGINCOURT NORTH QLD YAIN/HLS ARARAT VIC YARA/AD AGINCOURT SOUTH QLD YAIS/HLS ARARAT HOSPITAL VIC YXAR/HLS AGNES WATER QLD YAWT/ALA ARCADIA QLD YACI/ALA AGNEW QLD YAGN/ALA ARCHER RIVER QLD YARC/ALA AILERON NT YALR/ALA ARCKARINGA SA YAKG/ALA ALAMEIN SA YAMN/ALA ARCTURUS DOWNS HS QLD YATU/ALA ALBANY WA YABA/AD ARDGOUR NSW YADU/ALA ALBANY PARK NT YAPK/ALA ARDLETHAN NSW YARL/ALA ALBILBAH QLD YALH/ALA ARDMORE QLD YAOR/ALA ALBION DOWNS WA YABS/ALA ARDROSSAN HOSPITAL SA YXAN/HLS ALBURY NSW YMAY/AD AREYONGA NT YARN/ALA ALBURY HOSPITAL NSW YXAL/HLS ARGADARGADA NT YARD/ALA ALCOOTA STN NT YALC/ALA ARGYLE QLD YAGL/ALA ALDERLEY QLD YALY/ALA ARGYLE WA YARG/AD ALDERSYDE QLD YADR/ALA ARIZONA HS -

Kerwin 2006 01Thesis.Pdf (8.983Mb)

Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author Kerwin, Dale Wayne Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1614 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366276 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author: Dale Kerwin Dip.Ed. P.G.App.Sci/Mus. M.Phil.FMC Supervised by: Dr. Regina Ganter Dr. Fiona Paisley This dissertation was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts at Griffith University. Date submitted: January 2006 The work in this study has never previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any University and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this study contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the study itself. Signed Dated i Acknowledgements I dedicate this work to the memory of my Grandfather Charlie Leon, 20/06/1900– 1972 who took a group of Aboriginal dancers around the state of New South Wales in 1928 and donated half their gate takings to hospitals at each town they performed. Without the encouragement of the following people this thesis would not be possible. To Rosy Crisp, who fought her own battle with cancer and lost; she was my line manager while I was employed at (DATSIP) and was an inspiration to me. -

Final Repport

final reportp Northern Beef Program Project code: NBP.329 Prepared by: Dr David Phelps (Project Leader) Benjamin C Lynes Peter T Connelly Darrell J Horrocks Grant W Fraser Michael R Jeffery Department of Primary Industries & Fisheries Date published: April 2007 ISBN: 9781 741 912 241 PUBLISHED BY Meat & Livestock Australia Limited Locked Bag 991 NORTH SYDNEY NSW 2059 Sustainable Grazing in the Channel Country Floodplains (phase 2) A technical report on findings between March 2003 and June 2006 This publication is published by Meat & Livestock Australia Limited ABN 39 081 678 364 (MLA). Care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. However MLA cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in the publication. You should make your own enquiries before making decisions concerning your interests. Reproduction in whole or in part of this publication is prohibited without prior written consent of MLA. Sustainable Grazing in the Channel Country Floodplains (Phase 2) Abstract ‘Sustainable Grazing in the Channel Country Floodplains’ was initiated by industry to redress the lack of objective information for sustainable management in the floodplains of Cooper Creek and the Diamantina and Georgina Rivers. The project has maintained links with the grazing community and has extensively drawn upon expert local experience and knowledge. The project has provided tools for managers to better anticipate the size of beneficial flooding arising from rains in the upper catchment and to more objectively assess the value of the pasture resulting from flooding. The latest information from the project has enabled customisation of the EDGENetwork™ Grazing Land Management training package for the Channel Country. -

Report Title

Environmental Impact Report Operation of 1 MW Geothermal Power Plant at Innamincka Geodynamics Limited June 2014 Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Current Approvals .............................................................................................. 6 3.0 Proposed Activity and Location ........................................................................ 7 4.0 Operational Changes Since 2008 .................................................................... 13 4.1 Management System Changes ..................................................................................... 13 4.2 Operational Changes ..................................................................................................... 13 4.3 Geothermal Power Generation Process ........................................................................ 13 4.4 Geofluid Management.................................................................................................... 14 4.5 Site Offices, Power Plant and Facilities ......................................................................... 15 4.6 Power Plant Environmental Safeguards and Controls .................................................. 15 4.7 Wastewater Management .............................................................................................. 16 4.8 Power Generation and Energy Supply .......................................................................... 16 4.9 Fuel and Chemical -

Regional-Map-Outback-Qld-Ed-6-Back

Camooweal 160 km Burke and Wills Porcupine Gorge Charters New Victoria Bowen 138° Camooweal 139° 140° 141° Quarrells 142° 143° Marine fossil museum, Compton Downs 144° 145° 146° Charters 147° Burdekin Bowen Scottville 148° Roadhouse 156km Harrogate NP 18 km Towers Towers Downs 80 km 1 80 km 2 3 West 4 5 6 Kronosaurus Korner, and 7 8 WHITE MTNS Warrigal 9 Milray 10 Falls Dam 11 George Fisher Mine 139 OVERLANDERS 48 Nelia 110 km 52 km Harvest Cranbourne 30 Leichhardt 14 18 4 149 recreational lake. 54 Warrigal Cape Mt Raglan Collinsville Lake 30 21 Nonda Home Kaampa 18 Torver 62 Glendower NAT PARK 14 Biralee INDEX OF OUTBACK TOWNS AND Moondarra Mary Maxwelton 32 Alston Vale Valley C Corea Mt Malakoff Mt Bellevue Glendon Heidelberg CLONCURRY OORINDI Julia Creek 57 Gemoka RICHMOND Birralee 16 Tom’s Mt Kathleen Copper and Gold 9 16 50 Oorindi Gilliat FLINDERS A 6 Gypsum HWY Lauderdale 81 Plains LOCALITIES WITH FACILITIES 11 18 9THE Undha Bookin Tibarri 20 Rokeby 29 Blantyre Torrens Creek Victoria Downs BARKLY 28 Gem Site 55 44 Marathon Dunluce Burra Lornsleigh River Gem Site JULIA Bodell 9 Alick HWY Boree 30 44 A 6 MOUNT ISA BARKLY HWY Oonoomurra Pymurra 49 WAY 23 27 HUGHENDEN 89 THE OVERLANDERS WAY Pajingo 19 Mt McConnell TENNIAL River Creek A 2 Dolomite 35 32 Eurunga Marimo Arrolla Moselle 115 66 43 FLINDERS NAT TRAIL Section 3 Outback @ Isa Explorers’ Park interprets the World Rose 2 Torrens 31 Mt Michael Mica Creek Malvie Downs 52 O'Connell Warreah 20 Lake Moocha Lake Ukalunda Mt Ely A Historic Cloncurry Shire Hall, 25 Rupert Heritage listed Riversleigh Fossil Field and has underground mine tours. -

Aerodromes and Ala Codes

CODE - ENCODED 01 MAR 2018 IND - GEN - 1 AERODROMES AND ALA CODES - ENCODED LOCATION STATE CODE LOCATION STATE CODE ABBIEGLASSIE QLD YABG/ALA ANNA CREEK SA YANK/ALA ABC TV STUDIOS GORE HILL NSW YABC/HLS ANNA PLAINS HS WA YAPA/ALA ABERDEEN QLD YABD/ALA ANNANDALE QLD YADE/ALA ABERFOYLE QLD YABF/ALA ANNINGIE NT YANN/ALA ABINGDON DOWNS QLD YABI/ALA ANNITOWA NT YANW/ALA ACACIA DOWNS NSW YACS/ALA ANSWER DOWNS QLD YAND/ALA ADAMINABY NSW YADY/ALA ANTHONY LAGOON NT YANL/ALA ADAMINABY MEDICAL NSW YXAM/HLS ANTRIM QLD YANM/ALA ADAVALE QLD YADA/ALA APOLLO BAY VIC YAPO/ALA ADELAIDE SA YPAD/AD ARAMAC QLD YAMC/ALA ADELAIDE INTL RACEWAY SA YAIW/HLS ARAPUNYA NT YARP/ALA ADELAIDE OVAL SA YAOV/HLS ARARAT VIC YARA/AD ADELE ISLAND WA YADL/ALA ARARAT HOSPITAL VIC YXAR/HLS ADELS GROVE QLD YALG/ALA ARATULA QLD YAUL/ALA AGINCOURT NORTH QLD YAIN/HLS ARCADIA QLD YACI/ALA AGINCOURT SOUTH QLD YAIS/HLS ARCHER RIVER QLD YARC/ALA AGNES WATER QLD YAWT/ALA ARCHERFIELD QLD YBAF/AD AGNEW QLD YAGN/ALA ARCKARINGA SA YAKG/ALA AILERON NT YALR/ALA ARCTURUS DOWNS HS QLD YATU/ALA ALAMEIN SA YAMN/ALA ARDGOUR NSW YADU/ALA ALBANY WA YABA/AD ARDLETHAN NSW YARL/ALA ALBANY PARK NT YAPK/ALA ARDMORE QLD YAOR/ALA ALBILBAH QLD YALH/ALA AREYONGA NT YARN/ALA ALBION DOWNS WA YABS/ALA ARGADARGADA NT YARD/ALA ALBURY NSW YMAY/AD ARGYLE QLD YAGL/ALA ALBURY MEDICAL NSW YXAL/HLS ARGYLE WA YARG/AD ALCOOTA STN NT YALC/ALA ARIZONA HS QLD YARI/ALA ALDERLEY QLD YALY/ALA ARKAPENA SA YRKP/ALA ALDERSYDE QLD YADR/ALA ARKAROOLA SA YARK/ALA ALDINGA SA YADG/ALA ARLINGTON REEF QLD YARF/HLS ALEXANDRA VIC YAXA/HLS