~ ---V-O-'U-Rn-E-3 • Living Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programs and Activities 2019

For more information on these programs, unless Programs otherwise listed, please call the Cache River State Natural Area, Barkhausen-Cache and Activities River Wetlands Center at 618-657-2064. Please note that, while all programs are free of charge, some do require advance registration, as indicated. 2019 JANUARY Nature Movie: Snowy Owl Thursday, January 10, matinee 2-3pm, evening 6-7pm Cache River Wetlands Center Magic of the Snowy Owl Slide Tour: Springtime Birding in South Texas Saturday, January 26, 10-11am| Cache River Wetlands Center eaturing ancient cypress-tupelo swamps, FEBRUARY bottomland hardwood forests, sandstone Frog & Toad Survey Volunteer Orientation blu!s and limestone caves, the Cache Saturday, February 2, 1-3pm River Wetlands is a rich and diverse area Cache River Wetlands Center that provides habitat for many fascinating plants F and animals."e Cache is also a place where nature lovers of all ages can enjoy hiking, bicycling, kayaking and canoeing, hunting, #shing, birding and photography while learning more about this unique natural environment. Nature Movie: Ants Thursday, February 14, matinee 2-3pm, evening 6-7pm "is year, the Cache River State Natural Area Cache River Wetlands Center and Cypress Creek National Wildlife Refuge are o!ering many free, hands-on programs – so, bring your friends and family, and join us in exploring the wonderful world of the Cache! Ants: Little Creatures Who Run the World. A publication of the Friends of the Cache River Watershed Programs and Activities 2019 Slide -

Hardin County Area Map.Pdf

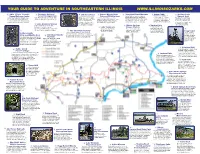

YOUR GUIDE TO ADVENTURE IN SOUTHEASTERN ILLINOIS WWW.ILLINOISOZARKS.COM 1 Ohio River Scenic 4 Shawnee National 3 Old Stone Face 6 Sahara Woods State 7 Stonefort Depot Museum 11 Camp Cadiz 15 Golden Circle This former coal mining area Byway Welcome Center Forest Headquarters A ½ mile moderately strenuous Fish and Wildlife Area Built in 1890, this former railroad depot Natural Arch is now a 2,300 acre state park On the corner in downtown Equality. View Main office for the national forest with visitor trail takes you to scenic vistas This former coal mining area is now a is a step back in time with old signs from This unique rock arch forms a managed for hunting and fishing. their extensive collection of artifacts from information, displays and souvenirs for sale. and one of the finest and natural 2,300 acre state park managed for hunting railroad companies and former businesses, natural amphitheater that was Plans are being developed for the salt well industry while taking advantage stone face rock formations. and fishing. Plans are being developed tools and machines from the heyday of the secret meeting place of a off-road vehicle recreation trails. of indoor restrooms and visitor’s information. Continue on the Crest Trail to for off-road vehicle recreation trails. railroads and telegraphs are on display. group of southern sympathizers, the Tecumseh Statue at Glen the Knights of the Golden 42 Lake Glendale Stables O Jones Lake 3 miles away. Circle, during the Civil War. Saddle up and enjoy an unforgettable 40 Hidden Springs 33 Burden Falls horseback ride no matter what your 20 Lake Tecumseh Ranger Station During wet weather, an intermittent stream spills experience level. -

Tunnel Hill 100 MILE RUN & 50 MILE RUN

Tunnel Hill 100 MILE RUN & 50 MILE RUN NOVEMBER 13, 2016 TUNNEL HILL STATE TRAIL Vienna, Illinois IN THE HEART OF JOHNSON COUNTY The citizens of Johnson County WOULD LIKE TO WELCOME YOU We encourage you to take advantage of all that Johnson County has to offer during your stay with us. Below is just a short list of attractions. Throughout this booklet you will find local restaurants, shops, and tourist destinations. We hope you enjoy your time and look forward to seeing you again! Shawnee National Forest 1-800-MY-WOODS Ferne Clyffe State Park South of Goreville, IL, (618) 995-2411 Paul Powell Home (Museum) Rt. 146 and Vine, Vienna, IL 62995 Vienna Depot Welcome Center Vienna City Park, Vienna, IL 62995, (618) 658-8547 Shawnee Hills Wine Trail (618) 967-4006, shawneewinetrail.com Cache River Wetlands Center THE JOHNSON COUNTY 8885 Rt. 37 S, Cypress, IL, (618) 657-2064 BOARD OF Johnson County’s Courthouse COMMISSIONERS and Carnegie Public Library ERNIE HENSHAW, PHIL STEWART Vienna, IL, both on the AND FRED MEYER National Registry of Historic Buildings Tunnel Hill 100/50 Mile Run - 2 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS FRIDAY NOVEMBER 12, 2016 Packet Pick up – 4 p.m. – 8 p.m. Pasta Dinner - 6 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. Vienna High School – 601 N 1st St, Vienna, IL 62995 SATURDAY NOVEMBER 13, 2016 Late packet pick up 6:30 – 7:30 a.m. Start – 100 mile and 50 mile 8:00 a.m. Finish – 100 & 50 mi. – Sun. Nov. 15 2 p.m. Vienna City Park – 298 E. -

Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team

Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team 2014 Annual Report Acknowledgements This program was funded through a grant supported by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy, and the River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area Contributions to this report were provided by: Nick Seaton and Caleb Grantham, Invasive Species Strike Team; Karla Gage, River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area; Jody Shimp, Natural Heritage Division, Illinois Department of Natural Resources; Tharran Hobson, The Nature Conservancy, and Fish and Wildlife Service. 2014’s field season has been dedicated to District Heritage Biologist, Bob Lindsay, whose dedication and insight to the Invasive Species Strike Team was greatly appreciated and will be sincerely missed. Equal opportunity to participate in programs of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and those funded by the U.S.D.A Forest Service and other agencies is available to all individuals regardless of race, sex, national origin, disability, age, religion or other non-merit factors. If you believe you have been discriminated against, contact the funding source’s civil rights office and/or the Equal Employment Opportunity Officer, IDNR, One Natural Resources Way, Springfield, IL. 62702-1271; 217/782-2262; TTY 217/782-9175. - 1 - | P a g e Executive Summary The Nature Conservancy, in partnership with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and the USDA Forest Service Northeast Area State and Private Forestry Program developed the Southern Illinois Invasive Species Strike Team (ISST) “formally known as the Southern Illinois Exotic Plant Strike Team” to control exotic plants in state parks, state nature preserves and adjacent private lands that serve as pathways onto these properties. -

Illinois State Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS ILLINOIS STATE PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. PRESERVATION WELCOME Energizing Welcome to Illinois! Thanks for picking up a copy of the adventure in partnership with Illinois State Parks guide to better plan your visit to our the National Parks Conservation remarkable state parks. Association. Illinois has an amazing array of state parks, fish and wildlife areas, and conservation and recreation areas, with an even broader selection of natural features and outdoor recreation opportunities. From the Lake Michigan shore at Illinois Beach to the canyons and waterfalls at Starved Rock; from the vistas above the mighty river at Mississippi Palisades to the hill prairies of Jim Edgar GO AND CONQUER Panther Creek; all the way to the sandstone walls of Giant City and the backwater swamps along the Cache River—Illinois has some of the most unique landscapes in America. -

Technical Report : Illinois Natural Areas Inventory

illliii'p ]i i iiiilffl,'isiPSi fJi J! ! tUl! on or '"'^" before ,he La.es. Da.e !;S;ed ^1" .H.'W I .') 2001 MAR JUL 14 ^4 I 3 2003 AUG 1 8 1994 JIOV J^;.; 'J 4 M J! J OCT 9 1996 14 m 1 3 Wr1337 2007 JUL 1 8 DEC 07 1997 »r! I 1997 APR 91998 MAR 1811393 LI6I—O-l09« ILLINOIS NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY TECHNICAL REPORT UNIVERSITY OF AT L . _ .-AIGN BOOKSIAQKa TECHNICAL REPORT ILLINOIS NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY performed under contract to the ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION by the DEPARTMENT OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS • URBANA-CHAMPAIGN and the NATURAL LAND INSTITUTE ROCKFORD, ILLINOIS This study was conducted for the State of Illinois pursuant to Contract #50-75-226 of the Illinois De- partment of Conservation. The study was financed in part through a planning grant from the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, U.S. Depart- ment of the Interior, under provisions of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (PL 88-578). Illinois Department of Conservation personnel re- sponsible for preparing the Request for Proposals and coordinating the work included John Schweg- man, contract liaison officer, and Dr. Edward Hoff- man, Dr. Robert Lee, Marlin Bowles, and Robert Schanzle. Published November 1978 Illinois Natural Areas Inventory, Urbana For additional Information Natural Areas Section Illinois Department of Conservation 605 Stratton Building Springfield, Illinois 62706 Dv\ '^^ Thf Illinois Natural Areas hwfutory u'os a 3-year project to find and describe natural areas for the Illinois Department of Consen'ation. -

THE ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTER January 1, 2019 Vol

THE ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTER January 1, 2019 Vol. 28, No.6 ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEWS COMPLETED • Red Hills State Park Project reviews completed from November 16 to December 1905001 - This project involves tree planting. Project 15 are listed below. These projects have been screened was submitted for review on 11-13-18. through the internal environmental review process for potential impacts on wetlands, threatened and endangered • Cache River State Natural Area species, and cultural and archaeological resources, etc. Through the review process it was determined that 1901179 - This project involves replacement and environmental impacts have been kept to a minimum and installation of interpretive signing at various trailheads mitigated as necessary, that they do not meet the criteria for and trails. Project was submitted for review on 8-3-18. significant actions as defined in the environmental review process, and may proceed. All these projects are in • Hopper Branch Savanna Nature Preserve compliance with the Endangered Species Protection Act, Natural Areas Preservation Act, Interagency Wetlands Policy 1905409 - This project involves forestry mowing to Act and cultural resource statutes. improve herbaceous vegetation growth. Project was submitted for review on 11-27-18. Dixon Springs State Park • • Rock Cut State Park 1902021 - This project will replace existing aluminum 1905322 - This project involves replacing the roof on the storm windows with vinyl double hung vinyl windows in site office building. Project was originally submitted for three Barracks buildings. Project was submitted for review on 11-21-18. review on 8-24-18. Market House-Galena • • Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site 1905559- This project involves replacing an aged air 1904794 – This project involves removal of 17 dead or conditioning unit for the restroom building. -

America's Natural Nuclear Bunkers

America’s Natural Nuclear Bunkers 1 America’s Natural Nuclear Bunkers Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 10 Alabama .............................................................................................................. 12 Alabama Caves .................................................................................................. 13 Alabama Mines ................................................................................................. 16 Alabama Tunnels .............................................................................................. 16 Alaska ................................................................................................................. 18 Alaska Caves ..................................................................................................... 19 Alaska Mines ............................................................................................... 19 Arizona ............................................................................................................... 24 Arizona Caves ................................................................................................... 25 Arizona Mines ................................................................................................... 26 Arkansas ............................................................................................................ 28 Arkansas Caves ................................................................................................ -

42 Life & Style

cover N O T W Evan Truesdale and Krystal Caronongan ride near Campus Lake at SIU. E N Both are experienced cyclists who work at The Bike Surgeon in Carbondale. UL PA 42 Life & Style : Summer 2013 story by Joe Szynkowski photography by Aaron Eisenhauer Tour and Paul Newton de Enjoyed by many, but untapped by most, Southern Illinois offers some of the best cycling experiences in the Midwest Adventure does not always require a passport and a plane ticket. As many people young and old have found, the region is a hotbed for some of the most challenging, rewarding cycling experiences the nation has to offer. It is adventure at its finest, and it is right here in Southern Illinois. Life & Style : Summer 2013 43 cover Cyclists make a sharp turn on Grassy Road during the Great Egyptian Omnium. t is a phrase that resurfaces “The beauty of cycling is that it is non- Events like the Great Egyptian Ominum as resolutely as the weekend impact and it is very easy on the body,” and Tour de Shawnee help show off the warriors who infiltrate local she said. “It is great cardio and it really has area’s versatility, history, and natural bike trails after spending their a lot of benefit for any population, from beauty, “Southern Illinois is a really good work weeks obsessing over their kids up to seniors.” cycling community,” said longtime rider next adventure. Its words combine Nevitt, who is also the Harrisburg Chad Briggs. “Being able to go right to form a statement both powerful and Township Parks and Recreation Director, outside your door and ride the hills we puzzling: Mountain biking is the best-kept has biked in locations across the country. -

Illinois Natural Heritage Conservation/Education Kit III

DOCUMENT RESUME ED'247 121 SE-044.717 AUTHOR Stone, Sally F. TITLE Illinois Natural Heritage Conservation/Education Kit III. Special Theme: Prairie and Open Habitats Ecology and Management. INSTITUTION' Illinois State Board of Education, Springfield.; Illinois State Dept. of Conservation; Springfield. PUB DATE May 83 NOTE 63p.; For other titles in this series, see SE 044 715-718. AVAILABLE FROMDepartment of Conservation, Forest Resources and National Heritage, 605 Stratton Office Building, Springfield, IL 62706. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Animals; Biology; Conservation (Environment); *Conservation Education; *Ecology; Elementary Secondary Education; Endangered Species; *Learning Activities; Plant Identification; Science Education; *Wildlife; *Wildlife Management __IDENTIFIERS *Illinois;_*Prairies ABSTRACT This instructional guide contains 15 activities and exercises designed to help teachers familiarize their students with' prairie and open habitat resources of Illinois. Each activity or exercise is ready to be copied and given to students. Activities include: (1) making a marsh hawk model; (2) building a prairie ecosystem; (3) investigating food chain links; (4) visiting aprairie (or an old field, pasture, grassy roadside, another open area if a prairie is not available); (4) working as a soil conservation specialist, wildlife manager, and conservation police officer; and (5) examining a fictional account taken from the journal of a young girl living and writing in modern day Illinois..The latter-is ,recommended for all students because it provides a broad overview of Illinois' prairie heritage. Although the materials are probably best suited for students in grades 4 -8, most of the activities can easily be adjusted to match the skill level of nearly every primary and secondary grade. -

Illinois Bike Trails Map

Illinois Bike Trails Map 8 21 Grand Illinois Trail 56 65 16 12 49 4 52 61 Statewide Trails 66 Northeast 1. Burnham Greenway The Route 66 Trail combines sections of Historic Route 66, nearby roads, and off-road 36 2. Busse Woods Bicycle Trail 30 37 trails for bicyclists and other non-motorized travelers. From Chicago to St. Louis, over 400 26 3. Centennial Trail 63 27 miles are available along three historic road alignments. See www. bikelib. org/ maps- and - 62 64 18 4. Chain O’ Lakes State Park Trails 5. Chicago Lakefront Path rides/ route-guides/route-66-trail/ for route information. To learn about the Historic Route 66 Rockford 60 6. Danada-Herrick Lake Regional Trail Scenic Byway, visit www.illinoisroute 66. org. For more information, contact the Illinois De- 40 7. Des Plaines River Trail (Cook County) 39 90 33 15 partment of Natural Resources, 217/782-3715. 7 8. Des Plaines River Trail (Lake County) 9. DuPage River Trail 35 Mississippi 2 10. East Branch DuPage River Greenway Trail The Grand Illinois Trail is a 500-mile loop of off-road trails and on-road bicycle routes, River 290 11. Fox River Trail ILL Trail 94 31 D IN 11 12. Grant Woods Forest Preserve Trail N O joined together across northern Illinois, stretching from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi 190 A 29 I 13. Great Western Trail (Kane & DeKalb counties) R S River. Metropolitan areas, rural small towns, historic landmarks, and scenic landscapes and 13 39 28 G 51 14. Great Western Trail (DuPage County) 53 59 50 294 parks are woven together by the Grand Illinois Trail, offering a superb bicycling experience. -

THE ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTER October 1, 2018 Vol

THE ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTER October 1, 2018 Vol. 28, No.3 ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEWS COMPLETED • Black Hawk State Historic Site Project reviews completed from August 16 to September 15 1901752 - This project involves removal of 12 hazardous are listed below. These projects have been screened trees within the day-use area, including aged oak trees, through the internal environmental review process for ashes impacted by ash borer, and other species. Project potential impacts on wetlands, threatened and endangered was submitted for review on 8-20-18. species, and cultural and archaeological resources, etc. Through the review process it was determined that • Giant City State Park environmental impacts have been kept to a minimum and mitigated as necessary, that they do not meet the criteria for 1901806 - This project involves repair & replacement of significant actions as defined in the environmental review roof systems on 8 vault toilet buildings and the doors on process, and may proceed. All these projects are in the privy located at Shelter #4. The existing roof compliance with the Endangered Species Protection Act, systems have out lived the expected life cycle and are Natural Areas Preservation Act, Interagency Wetlands Policy beginning to deteriorate. Project was submitted for Act and cultural resource statutes. review on 8-21-2018. Giant City State Park • • Fort Massac State Park 1901191 - This project will add 2 Mitsubishi AC units to 1901702 - This project involves construction of five small improve the working conditions with in the kitchen area. cabins, approximately 15’x20’, elevated approximately The blower unit will be installed in the kitchen area, 3’ off the ground due to location within a flood zone.