Human Rights Implications of Crime Control in the Digital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Leaders in Indian Political Parties and Their Contribution and Struggles

International Journal of Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity Vol.11, No. 3, (2020), pp. 2641–2647 Women Leaders In Indian Political Parties And Their Contribution And Struggles 1K.Nithila, 2Dr.V.Veeramuthu, Ph.D., Ph.D. Scholar, Head of the Department, Department Of Political Science, Department Of Political Science, Government Arts College (Autonomous), Government Arts College (Autonomous), Salem-636007, Salem-636007, Abstract: The making of the Constitution brought women legal equality. Though the constitutional provisions allowed the women to leave the relative calm of the domestic sphere to enter the male- dominated political sphere, the involvement of women in politics has been low key. The political contribution of women is a social process crucial to development and progress. The status of women is measured internationally by the participation of women in politics and their empowerment. Women remain seriously underrepresented in decision-making positions. but still, awareness should be created among women to participate in politics with courage. The findings on the participation of women in politics are increasing. It is significant in the study on political empowerment and participation of women in politics. To secure women’s rightful place in society and to enable them to decide their destiny and for the growth of genuine and sustainable democracy, women's participation in politics is essential. This will not only uplift their personality but will open the way for their social and economic empowerment. Their contribution to public life will solve many problems in society. It concludes that the participation of women is essential as demand for simple justice as well as a necessary condition for human existence. -

Justice for Jessica: a Human Rights Case Study on Media Influence, Rule of Law, and Civic Action in India Lisette Alvarez

Florida State University Libraries Honors Theses The Division of Undergraduate Studies 2011 Justice for Jessica: A Human Rights Case Study on Media Influence, Rule of Law, and Civic Action in India Lisette Alvarez Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] Alvarez1 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to explore the impact and implications of various aspects of the Jessica Lal murder trial, understanding that many factors of Indian society contributed to both the murder and the outcome. This paper will focus on a number of specific aspects of the trial and assess their significance for human rights issues: journalism in India, social media and public participation in civic action, Indian film and its direct influence on the trial, structural issues in the police and judicial system, purpose and actions of local and international human rights organizations, and the ongoing 2011 anti-corruption movement in India. However, in order to properly contextualize the Jessica Lal case and its components within modern Indian society, it is necessary to identify a number of other criminal cases that are similar in relation to social issues. As a human rights study of a political and social phenomenon, this paper will attempt to answer certain questions: In what way does the modern use of technology and social media impact journalism and social activism? Is there a culture of violence against women in India, and if so, why, and how is it viewed in India? What successes and problems have Indian society encountered in terms of minimizing corruption in the police and judicial system? The paper will examine as well as look for the different answers to these questions in a format that engages many contributing factors that aid in the explanation, reasoning, and definition of human rights issues in India. -

Trial by Media – a Discord of Rights

TRIAL BY MEDIA – A DISCORD OF RIGHTS By Swatilekha Chakraborty422 INTRODUCTION One of the pillars of any democratic nation is the freedom to free speech and expression. It is a core freedom without which a democracy cannot survive. The fact that people can voice their opinions without any fear forms one of the very important characteristics of any democracy. In India, this right can be found deeply embedded under Article 19(a) of the Constitution. This right, by judicial interpretation also includes inter alia the freedom of press. The importance of freedom of press has been recognized world-wide, because of the crucial role it plays in the political development and social upliftment. The issue was discussed at lengths at the Dakar Conference on World Press Freedom in 2005 wherein it was stated that “An independent, free and pluralistic media have a crucial role to play in the good governance of democratic societies, by ensuring transparency and accountability, promoting participation and the rule of law, and contributing to the fight against poverty.” The importance of this right despite being widely recognized the chances of unlimited right being misused cannot be ignored. To curb such misuse, certain restrictions have been put on the same by Article 19(2) of the Constitution. The need to reasonably restrict the freedom of press has also been reiterated time and again by various Indian courts. 423 TRIAL BY MEDIA: THE PHENOMENA The idea that popular media can have a strong influence on the legal processes is well known and goes back as early as the advent of the printing press. -

SC Restrains Italian Ambassador from Leaving India

“Indian Air Force has Your World Connected a critical role to play to safeguard our Vol. 2 Issue 11 10.00 24 Pages territorial integrity,” RNI Reg. No.: PUNMUL/2012/45041 Postal Reg. No. PB/JL-047/2013-15 SUNDAY 17 MARCH 2013 The President of India, Weekly Newspaper Shri Pranab Mukherjee www.facebook.com/uconnectt National 4 International 6 Campus 10 Celebrity 14 Leisure 16 Business 20 Sports 22 Fidayeen attack CRPF troopers in Kashmir Page 5 Xi Jinping the new Chinese president Page 6 Cinema more organised now, says Sridevi Page 13 I am 16 Page 15 SC restrains Italian ambassador from leaving India India collects 8 medals at Asian The Supreme Court restrained Italian ambassador Daniele Mancini from leaving the country till March 18 without its permission. Archery Grand Prix The apex court bench, headed by Chief Justice Altamas Kabir, while restraining the Italian ambassador from leaving the country, issued notice to the Italian government, its ambassador, and the two marines accused of killing two Indian fishermen Feb 15, 2012. The court said the notices are returnable by March 18. The Italian ambassador was issued notice on going back on his undertaking to the court assuring the return of the two marines after their four weeks’ stay in Italy. The court issued the notice after Attorney General G.E. Vahanvati informed the court about the sequence of events starting from the Italian government’s statement that the two marines will not return Page 23 to India to face trial after the expiry of four weeks for which they were allowed to visit their country. -

Women Leaders in Indian Political Parties and Their Contribution and Struggles

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 Women Leaders In Indian Political Parties And Their Contribution And Struggles. K.NITHILA, Dr.V.VEERAMUTHU, Ph.D., Ph.D. Scholar, Head of the Department, Department Of Political Science, Department Of Political Science, Government Arts College (Autonomous), Government Arts College (Autonomous), Salem-636007, Salem-636007, Abstract: The making of the Constitution brought women legal equality. Though the constitutional provisions allowed the women to leave the relative calm of the domestic sphere to enter the male-dominated political sphere, the involvement of women in politics has been low key. The political contribution of women is a social process crucial to development and progress. The status of women is measured internationally by the participation of women in politics and their empowerment. Women remain seriously underrepresented in decision-making positions. but still, awareness should be created among women to participate in politics with courage. The findings on the participation of women in politics are increasing. It is significant in the study on political empowerment and participation of women in politics. To secure women’s rightful place in society and to enable them to decide their destiny and for the growth of genuine and sustainable democracy, women's participation in politics is essential. This will not only uplift their personality but will open the way for their social and economic empowerment. Their contribution to public life will solve many problems in society. It concludes that the participation of women is essential as demand for simple justice as well as a necessary condition for human existence. This can be achieved not just by increasing the numbers but by ensuring that women leaders perceive the problems and effectively resolve the issues. -

Indian Freedom Struggle- I

IndianFreedomStruggle I/ IndianFreedomStruggle II DHIS204/DHIS205 Edited by Dr. Manu Sharma Dr. Santosh Kumar INDIAN FREEDOM STRUGGLE- I INDIAN FREEDOM STRUGGLE- II Edited By: Dr. Manu Sharma and Dr. Santosh Kumar Printed by USI PUBLICATIONS 2/31, Nehru Enclave, Kalkaji Ext., New Delhi-110019 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS DHI IS204 Indian Freedom Struggle - I Objectives 1. To introduce students with different phases of freedom struggle 2. To make them understand the policies and strategies of British Government 3. To acquaint students with the sacrifices of our freedom martyrs Sr. No. Topics 1. British Expansion: Carnatic wars, Anglo Mysore wars, Anglo Maratha wars 2. Political Establishment: Battle of Plassey, Battle of Buxar, Reforms of Lord Clive 3. Consolidation of the British Raj: Development of Central structure, Changes in Economic Policy and Educational Policy 4. Constitutional Development: Regulating Act 1773 and Pitt’s India Act 1784 5. Implementation of Imperial Policies: Reforms of Cornwallis, Reforms of William Bentinck 6. Age of Reforms: Reforms of Lord Dalhousie 7. Reformist Movements: Brahmo Samaj and Singh Sabha Movement 8. Revivalist Movements: Arya Samaj 9. The First Major Challenge 1857: Causes of revolt, Events, Causes for the failure, Aftermath 10. Maps: Important Centers of the Revolt of 1857 & India before independence DHI IS205 Indian Freedom Struggle - II Sr. No. Topics 1. Establishment of Indian National Congress: Factors responsible for its foundation, Theories of its origin, Moderates and Extremists 2. Home Rule League: Role of Lokmanya Tilak and Annie Besant, its fallout 3. Non Cooperation Movement: Circumstances leading to the movement, Events, Impact 4. Civil Disobedience Movement: Circumstances leading to the movement, Events 5. -

Media Trial: the Judgement Before Judge’S One Krishna Yadav & Shruti Agarwal

I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 LEX FORTI L E G A L J O U R N A L V O L - I I S S U E - I V A P R I L 2 0 2 0 I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form by any means without prior written permission of Editor-in-chief of LexForti Legal Journal. The Editorial Team of LexForti Legal Journal holds the copyright to all articles contributed to this publication. The views expressed in this publication are purely personal opinions of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Editorial Team of LexForti. Though all efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published, LexForti shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to oversight otherwise. I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 EDITORIAL BOARD E D I T O R I N C H I E F R O H I T P R A D H A N A D V O C A T E P R I M E D I S P U T E P H O N E - + 9 1 - 8 7 5 7 1 8 2 7 0 5 E M A I L - L E X . F O R T I I @ G M A I L . C O M E D I T O R I N C H I E F M S . -

A Brat, a Struggling Model, the Law & the Media

I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 LEX FORTI L E G A L J O U R N A L V O L - I I S S U E - V J U N E 2 0 2 0 I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 DISCLAIMER N O P A R T O F T H I S P U B L I C A T I O N M A Y B E R E P R O D U C E D O R C O P I E D I N A N Y F O R M B Y A N Y M E A N S W I T H O U T P R I O R W R I T T E N P E R M I S S I O N O F E D I T O R - I N - C H I E F O F L E X F O R T I L E G A L J O U R N A L . T H E E D I T O R I A L T E A M O F L E X F O R T I L E G A L J O U R N A L H O L D S T H E C O P Y R I G H T T O A L L A R T I C L E S C O N T R I B U T E D T O T H I S P U B L I C A T I O N . -

MEDIA – a VALUABLE MEANS to JUSTICE Written by Monisha Gade Assistant Professor in Law

Open Access Journal available at www.jlsr.thelawbrigade.com 89 MEDIA – A VALUABLE MEANS TO JUSTICE Written By Monisha Gade Assistant Professor in Law INTRODUCTION: India is the seventh largest democratic country in the world. India has a vast political history. It has been ruled by various kings. India has undergone various changes in 20th century. India was under the colonial rule for over two centuries. In 1947, India got independence from the brutal clutches of British rule. After independence framers of the constitution has adopted to it a democratic form of government after studying various forms of government. India is a country with a diverse population belonging to various religions, races, castes and creed. Traditionally called as HINDUSTAN, India is homeland to people belonging to different religions like Hindus, Muslims, and Christians etc. democracy means of the people, by the people and for the people. This means India has a government which is elected by the people for themselves. The Indian Constitution was framed with utmost care that it provides various freedoms and liberties to its citizens. Part III of the Indian Constitution contains Articles 12 to 35 which enshrine fundamental rights. Every democratic government is based on four essential pillars. The Indian Union constitutes of four pillars. They are called as Legislature, Executive, Judiciary and Media. The Indian Constitution provides framework for the first three estates. But there is no mention of media as fourth estate in Indian Constitution. All the three estates are independent of each other. They have a complete sovereignty in their field. Media being a fourth estate has a prominent role in the success of democracy. -

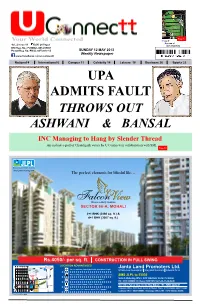

Upa Admits Fault

Page 3 Your World Connected ‘Caged’ Bureau of Vol. 2 Issue 19 10.00 24 Pages Investigation RNI Reg. No.: PUNMUL/2012/45041 Postal Reg. No. PB/JL-047/2013-15 SUNDAY 12 MAY 2013 Weekly Newspaper www.facebook.com/uconnectt National 4 International 6 Campus 11 Celebrity 14 Leisure 16 Business 20 Sports 22 UPA ADMITS FAULT THROWS OUT ASHWANI & BANSAL INC Managing to Hang by Slender Thread An exclusive poll of Chandigarh voters by U Connectt in collaboration with SMI Page 13 CHANDIGARH 2 OPINION SUNDAY 12 May 2013 EDITORIAL DESK Manu Sharma BJP Lacks Realpolitik Bharatiya Janata Party was tradition- For any political party in any other incompetence and lack of realpolitik LOUD & CLEAR ally known as a political party with country of the world such issues in governance. Politics by its nature S.K. Sinha its base firmly entrenched in the would have been treated as part of demands that no principal or ideology Northern States of India. The party the play and sorted with sagacity of be ultimate when juxtaposed with ex- was finally able to change that image a surgeon’s scalpel. Instead the party igencies of governance. When BJP is ‘Mother’ is a verb , by storming to power in the Southern let these issues become crude ma- looking to make corruption and gov- state of Karnataka in 2008. Led by chetes with which it managed to hack ernance as issues for next elections, it not a noun maverick Lingayat leader BS Yed- its own limbs off in the run up to the must remember that all of its prom- dyurappa, BJP rose fast and grew state elections. -

India: Independence of and Corruption Within the Judicial System (2007 - April 2009) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 23 April 2009 IND103122.E India: Independence of and corruption within the judicial system (2007 - April 2009) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa Transparency International (TI) provides the following summary of India's judicial system: India's court system consists of a Supreme Court, high courts at state level and subordinate courts at district and local level. The Supreme Court comprises a Chief Justice and no more than 25 other judges appointed by the president. The Supreme Court has a special advisory role on topics that the president may specifically refer to it. High courts have power over lower courts within their respective states, including posting, promotion and other administrative functions. Judges of the Supreme Court and the high court cannot be removed from office except by a process of impeachment in parliament. Decisions in all courts can be appealed to a higher judicial authority up to the Supreme Court level. (2007, 215) Article 50 of the Constitution of India provides for the independence of the judiciary, stating that "[t]he State shall take steps to separate the judiciary from the executive in the public services of the State" (India 1 Dec. 2007, Art. 50). Article 124 of India's Constitution states the following in regard to appointment, tenure and impeachment: (2) [e]very judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President … after consultation with such of the Judges of the Supreme Court and of the High Courts in the States as the President deems necessary for the purpose and shall hold office until he attains the age of sixty-five years. -

A Content Analysis of Four English Language Newspapers

Journal Media and Communication Studies Vol. 2(2) pp. 039-053, February, 2010 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/jmcs © 2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Trends in first page priorities of Indian print media reporting - A content analysis of four English Language newspapers C. S. H. N. Murthy1*, Challa Ramakrishna2 and Srinivas R. Melkote3 1Manipal Institute of Communication, Press Corner, Manipal University, Manipal, Karnataka 576 104 India. 2Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, A.P. 530 003, India. 3School of Communication Studies, Dept of Telecommunications, 302 West Hall, Bowling Green State University, Ohio 43403-0233, USA. Accepted 21 December, 2009 A critical analysis of the first page reporting priorities of the four leading news papers- The Hindustan Times, The Indian Express, The Times of India (all being published from New Delhi and Lucknow) and The Hindu (Only from New Delhi and Southern States) reveals a number of interesting shifts in the paradigms of news reporting and values. The analysis, which involves the first page news coverage (including headlines, type of content, photos and advertisements), offered an insight into the departures from the traditional news values. The study has witnessed a growing trend for first reporting and investigative reporting, treating news as a commercialized commodity for mass consumption, filled with crime, legal disputes, politics, etc. with economic, social and development news taking a backseat. The pages of the news papers are filled with increased use of large and small color photos (especially photos of the main players in each story), and the use of long titles and large fonts for even short reports to make up the space of the first page look compact, suggesting a crisis for news due to intense competition and acquiring contours of magazine journalism/tabloidization.