Smith-F.J.D.-2009.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PGD: a Celebration of 20 Years

PGD: A Celebration of 20 years: What is Reality and What is Not? Roma June 30, 2010 Mark Hughes, M.D., Ph.D . Professor of Genetics, Internal Medicine, Pathology Director, Genesis Genetics Institute Director, State of Michigan Genomic Technology Center Reality – (Three obvious ones) PGD • Has led to the birth of thousands of healthy children to very desperate, genetically at-risk couples. • Remains at the very limit of medical diagnostic testing • The technology continues to improve - – but it is not reality to think PGD will ever have a 0% false positive or false negative rate Reality: We still do not know What is best to biopsy, and when? Polar Body Blastomere Trophoectoderm Variation in Biopsy Skill Clinic Biopsies +HCG / ET 1 314 17% 2 427 26% 3 181 12% 4 712 31% Reality: We all are controversial • PGD has raised international controversy – How is it bioethically different from Prenatal Testing? – Who should control the use of these technologies? – Should there be government PGD testing standards? • What is the difference between a Disease and a Trait - and who decides? PGD Disorders (A, B, C) • ACHONDROPLASIA (FGFR) • BARTH DILIATED CARDIOMYOPATHY • ACTIN-NEMALIN MYOPATHY (ACTA) • BETA THALASSEMIA (HBB) • ADRENOLEUKODYSTROPHY (ABCD) • BLOOM SYNDROME • AGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA-BRUTON (TYKNS) • BREAST CANCER (BRCA1 & 2) • ALAGILLE SYNDROME (JAG) • CACH-ATAXIA (EIFB) • ALDOLASE A, FRUCTOSE-BISPHOSPHATE • CADASIL (NOTCH) • ALPHA THALASSEMIA (HBA) • CANAVAN DISEASE (ASPA) • ALPHA-ANTITRYPSIN (AAT) • CARNITINE-ACYLCARN TRANSLOCASE • ALPORT SYNDROME -

Associated Palmoplantar Keratoderma

DR ABIGAIL ZIEMAN (Orcid ID : 0000-0001-8236-207X) Article type : Review Article Pathophysiology of pachyonychia congenita-associated palmoplantar keratoderma: New insight into skin epithelial homeostasis and avenues for treatment Authors: A. G. Zieman1 and P. A. Coulombe1,2 # Affiliations: 1Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; 2Department of Dermatology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA #Corresponding author: Pierre A. Coulombe, PhD, 3071 Biomedical Sciences Research Building, 109 Zina Pitcher Place, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA. Tel: 734-615-7509. Email: [email protected]. Funding Sources: These studies were supported by grant AR044232 issued to P.A.C. from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (NIAMS). A.G.Z. received support from grant T32 CA009110 from the National Cancer Institute. Author Manuscript This is the author manuscript accepted for publication and has undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/BJD.18033 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved Conflict of interest disclosures: None declared. Bulleted statements: What’s already known about this topic? Pachyonychia congenita is a rare genodermatosis caused by mutations in KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT6C, KRT16, KRT17, which are normally expressed in skin appendages and induced following injury. Individuals with PC present with multiple clinical symptoms that usually include thickened and dystrophic nails, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), glandular cysts, and oral leukokeratosis. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

Supplementary File 2A Revised

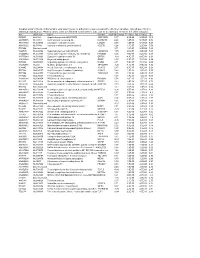

Supplementary file 2A. Differentially expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared to all other samples, ranked according to statistical significance. Missing values were not allowed in aldosteronomas, but to a maximum of five in the other samples. Acc UGCluster Name Symbol log Fold Change P - Value Adj. P-Value B R99527 Hs.8162 Hypothetical protein MGC39372 MGC39372 2,17 6,3E-09 5,1E-05 10,2 AA398335 Hs.10414 Kelch domain containing 8A KLHDC8A 2,26 1,2E-08 5,1E-05 9,56 AA441933 Hs.519075 Leiomodin 1 (smooth muscle) LMOD1 2,33 1,3E-08 5,1E-05 9,54 AA630120 Hs.78781 Vascular endothelial growth factor B VEGFB 1,24 1,1E-07 2,9E-04 7,59 R07846 Data not found 3,71 1,2E-07 2,9E-04 7,49 W92795 Hs.434386 Hypothetical protein LOC201229 LOC201229 1,55 2,0E-07 4,0E-04 7,03 AA454564 Hs.323396 Family with sequence similarity 54, member B FAM54B 1,25 3,0E-07 5,2E-04 6,65 AA775249 Hs.513633 G protein-coupled receptor 56 GPR56 -1,63 4,3E-07 6,4E-04 6,33 AA012822 Hs.713814 Oxysterol bining protein OSBP 1,35 5,3E-07 7,1E-04 6,14 R45592 Hs.655271 Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2 RIMS2 2,51 5,9E-07 7,1E-04 6,04 AA282936 Hs.240 M-phase phosphoprotein 1 MPHOSPH -1,40 8,1E-07 8,9E-04 5,74 N34945 Hs.234898 Acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 0,87 9,7E-07 9,8E-04 5,58 R07322 Hs.464137 Acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl ACOX1 0,82 1,3E-06 1,2E-03 5,35 R77144 Hs.488835 Transmembrane protein 120A TMEM120A 1,55 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,07 H68542 Hs.420009 Transcribed locus 1,07 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,06 AA410184 Hs.696454 PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 2 PKNOX2 1,78 2,0E-06 -

140503 IPF Signatures Supplement Withfigs Thorax

Supplementary material for Heterogeneous gene expression signatures correspond to distinct lung pathologies and biomarkers of disease severity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Daryle J. DePianto1*, Sanjay Chandriani1⌘*, Alexander R. Abbas1, Guiquan Jia1, Elsa N. N’Diaye1, Patrick Caplazi1, Steven E. Kauder1, Sabyasachi Biswas1, Satyajit K. Karnik1#, Connie Ha1, Zora Modrusan1, Michael A. Matthay2, Jasleen Kukreja3, Harold R. Collard2, Jackson G. Egen1, Paul J. Wolters2§, and Joseph R. Arron1§ 1Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, CA 2Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA 3Department of Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, CA ⌘Current address: Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, Emeryville, CA. #Current address: Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA. *DJD and SC contributed equally to this manuscript §PJW and JRA co-directed this project Address correspondence to Paul J. Wolters, MD University of California, San Francisco Department of Medicine Box 0111 San Francisco, CA 94143-0111 [email protected] or Joseph R. Arron, MD, PhD Genentech, Inc. MS 231C 1 DNA Way South San Francisco, CA 94080 [email protected] 1 METHODS Human lung tissue samples Tissues were obtained at UCSF from clinical samples from IPF patients at the time of biopsy or lung transplantation. All patients were seen at UCSF and the diagnosis of IPF was established through multidisciplinary review of clinical, radiological, and pathological data according to criteria established by the consensus classification of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS), Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS), and the Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) (ref. 5 in main text). Non-diseased normal lung tissues were procured from lungs not used by the Northern California Transplant Donor Network. -

WES Gene Package Multiple Congenital Anomalie.Xlsx

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Multiple congenital anomalie, version 5, 1‐2‐2018 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect Clinical Research Exome V2 capture and paired‐end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 8.1 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA‐MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio‐bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x A4GALT [Blood group, P1Pk system, P(2) phenotype], 111400 607922 101 100 100 99 [Blood group, P1Pk system, p phenotype], 111400 NOR polyagglutination syndrome, 111400 AAAS Achalasia‐addisonianism‐alacrimia syndrome, 231550 605378 73 100 100 100 AAGAB Keratoderma, palmoplantar, -

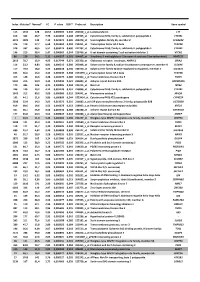

Index Mutated* Normal* FC P Value FDR** Probe Set Description Gene Symbol

Index Mutated* Normal* FC P value FDR** Probe set Description Gene symbol 113 1342 128 10,52 0,000503 0,240 202018_s_at Lactotransferrin LTF 616 362 46,7 7,76 0,003493 0,308 237395_at Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily Z, polypeptide 1 CYP4Z1 3073 1009 142 7,10 0,021674 0,385 206378_at Secretoglobin, family 2A, member 2 SCGB2A2 376 119 17,7 6,68 0,001962 0,284 214451_at Transcription factor AP-2 beta TFAP2B 578 337 60,5 5,57 0,003174 0,300 227702_at Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily X, polypeptide 1 CYP4X1 146 210 38,4 5,47 0,000669 0,244 219768_at V-set domain containing T cell activation inhibitor 1 VTCN1 86 129 24,2 5,31 0,000327 0,201 204607_at 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A synthase 2 (mitochondrial) HMGCS2 2613 78,7 15,9 4,95 0,017744 0,371 205358_at Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 2 GRIA2 116 23,2 4,83 4,81 0,000513 0,240 203908_at Solute carrier family 4, sodium bicarbonate cotransporter, member 4 SLC4A4 117 79,4 18,0 4,42 0,000518 0,240 239723_at Solute carrier family 40 (iron-regulated transporter), member 1 SLC40A1 625 56,6 13,0 4,34 0,003549 0,308 1553394_a_atTranscription factor AP-2 beta TFAP2B 413 148 34,6 4,28 0,002175 0,286 240304_s_at Transmembrane channel-like 5 TMC5 5181 216 50,9 4,25 0,039946 0,421 223864_at Ankyrin repeat domain 30A ANKRD30A 179 446 106 4,21 0,000826 0,244 223315_at Netrin 4 NTN4 246 120 29,2 4,12 0,001128 0,251 210096_at Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 CYP4B1 1043 312 80,2 3,89 0,006080 0,319 204041_at Monoamine oxidase B MAOB 192 44,1 11,6 3,80 0,000899 0,244 -

Proteomic Expression Profile in Human Temporomandibular Joint

diagnostics Article Proteomic Expression Profile in Human Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction Andrea Duarte Doetzer 1,*, Roberto Hirochi Herai 1 , Marília Afonso Rabelo Buzalaf 2 and Paula Cristina Trevilatto 1 1 Graduate Program in Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR), Curitiba 80215-901, Brazil; [email protected] (R.H.H.); [email protected] (P.C.T.) 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Bauru School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, Bauru 17012-901, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-41-991-864-747 Abstract: Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) is a multifactorial condition that impairs human’s health and quality of life. Its etiology is still a challenge due to its complex development and the great number of different conditions it comprises. One of the most common forms of TMD is anterior disc displacement without reduction (DDWoR) and other TMDs with distinct origins are condylar hyperplasia (CH) and mandibular dislocation (MD). Thus, the aim of this study is to identify the protein expression profile of synovial fluid and the temporomandibular joint disc of patients diagnosed with DDWoR, CH and MD. Synovial fluid and a fraction of the temporomandibular joint disc were collected from nine patients diagnosed with DDWoR (n = 3), CH (n = 4) and MD (n = 2). Samples were subjected to label-free nLC-MS/MS for proteomic data extraction, and then bioinformatics analysis were conducted for protein identification and functional annotation. The three Citation: Doetzer, A.D.; Herai, R.H.; TMD conditions showed different protein expression profiles, and novel proteins were identified Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Trevilatto, P.C. -

Copyrighted Material

Part 1 General Dermatology GENERAL DERMATOLOGY COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Handbook of Dermatology: A Practical Manual, Second Edition. Margaret W. Mann and Daniel L. Popkin. © 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Published 2020 by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 0004285348.INDD 1 7/31/2019 6:12:02 PM 0004285348.INDD 2 7/31/2019 6:12:02 PM COMMON WORK-UPS, SIGNS, AND MANAGEMENT Dermatologic Differential Algorithm Courtesy of Dr. Neel Patel 1. Is it a rash or growth? AND MANAGEMENT 2. If it is a rash, is it mainly epidermal, dermal, subcutaneous, or a combination? 3. If the rash is epidermal or a combination, try to define the SIGNS, COMMON WORK-UPS, characteristics of the rash. Is it mainly papulosquamous? Papulopustular? Blistering? After defining the characteristics, then think about causes of that type of rash: CITES MVA PITA: Congenital, Infections, Tumor, Endocrinologic, Solar related, Metabolic, Vascular, Allergic, Psychiatric, Latrogenic, Trauma, Autoimmune. When generating the differential, take the history and location of the rash into account. 4. If the rash is dermal or subcutaneous, then think of cells and substances that infiltrate and associated diseases (histiocytes, lymphocytes, mast cells, neutrophils, metastatic tumors, mucin, amyloid, immunoglobulin, etc.). 5. If the lesion is a growth, is it benign or malignant in appearance? Think of cells in the skin and their associated diseases (keratinocytes, fibroblasts, neurons, adipocytes, melanocytes, histiocytes, pericytes, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, follicular cells, sebocytes, eccrine -

1 No. Affymetrix ID Gene Symbol Genedescription Gotermsbp Q Value 1. 209351 at KRT14 Keratin 14 Structural Constituent of Cyto

1 Affymetrix Gene Q No. GeneDescription GOTermsBP ID Symbol value structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 1. 209351_at KRT14 keratin 14 filament, epidermis development <0.01 biological process unknown, S100 calcium binding calcium ion binding, cellular 2. 204268_at S100A2 protein A2 component unknown <0.01 regulation of progression through cell cycle, extracellular space, cytoplasm, cell proliferation, protein kinase C inhibitor activity, protein domain specific 3. 33323_r_at SFN stratifin/14-3-3σ binding <0.01 regulation of progression through cell cycle, extracellular space, cytoplasm, cell proliferation, protein kinase C inhibitor activity, protein domain specific 4. 33322_i_at SFN stratifin/14-3-3σ binding <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 5. 201820_at KRT5 keratin 5 filament, epidermis development <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 6. 209125_at KRT6A keratin 6A filament, ectoderm development <0.01 regulation of progression through cell cycle, extracellular space, cytoplasm, cell proliferation, protein kinase C inhibitor activity, protein domain specific 7. 209260_at SFN stratifin/14-3-3σ binding <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 8. 213680_at KRT6B keratin 6B filament, ectoderm development <0.01 receptor activity, cytosol, integral to plasma membrane, cell surface receptor linked signal transduction, sensory perception, tumor-associated calcium visual perception, cell 9. 202286_s_at TACSTD2 signal transducer 2 proliferation, membrane <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, cytoskeleton, intermediate filament, cell-cell adherens junction, epidermis 10. 200606_at DSP desmoplakin development <0.01 lectin, galactoside- sugar binding, extracellular binding, soluble, 7 space, nucleus, apoptosis, 11. 206400_at LGALS7 (galectin 7) heterophilic cell adhesion <0.01 2 S100 calcium binding calcium ion binding, epidermis 12. 205916_at S100A7 protein A7 (psoriasin 1) development <0.01 S100 calcium binding protein A8 (calgranulin calcium ion binding, extracellular 13. -

Pili Torti: a Feature of Numerous Congenital and Acquired Conditions

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Pili Torti: A Feature of Numerous Congenital and Acquired Conditions Aleksandra Hoffmann 1 , Anna Wa´skiel-Burnat 1,*, Jakub Z˙ ółkiewicz 1 , Leszek Blicharz 1, Adriana Rakowska 1, Mohamad Goldust 2 , Małgorzata Olszewska 1 and Lidia Rudnicka 1 1 Department of Dermatology, Medical University of Warsaw, Koszykowa 82A, 02-008 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (A.H.); [email protected] (J.Z.);˙ [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (M.O.); [email protected] (L.R.) 2 Department of Dermatology, University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University, 55122 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-5021-324; Fax: +48-22-824-2200 Abstract: Pili torti is a rare condition characterized by the presence of the hair shaft, which is flattened at irregular intervals and twisted 180◦ along its long axis. It is a form of hair shaft disorder with increased fragility. The condition is classified into inherited and acquired. Inherited forms may be either isolated or associated with numerous genetic diseases or syndromes (e.g., Menkes disease, Björnstad syndrome, Netherton syndrome, and Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome). Moreover, pili torti may be a feature of various ectodermal dysplasias (such as Rapp-Hodgkin syndrome and Ankyloblepharon-ectodermal defects-cleft lip/palate syndrome). Acquired pili torti was described in numerous forms of alopecia (e.g., lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus erythematosus, dissecting Citation: Hoffmann, A.; cellulitis, folliculitis decalvans, alopecia areata) as well as neoplastic and systemic diseases (such Wa´skiel-Burnat,A.; Zółkiewicz,˙ J.; as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, scalp metastasis of breast cancer, anorexia nervosa, malnutrition, Blicharz, L.; Rakowska, A.; Goldust, M.; Olszewska, M.; Rudnicka, L. -

Transcriptome Profiling and Differential Gene Expression In

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Transcriptome Profiling and Differential Gene Expression in Canine Microdissected Anagen and Telogen Hair Follicles and Interfollicular Epidermis Dominique J. Wiener 1,* ,Kátia R. Groch 1 , Magdalena A.T. Brunner 2,3, Tosso Leeb 2,3 , Vidhya Jagannathan 2 and Monika M. Welle 3,4 1 Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA; [email protected] 2 Institute of Genetics, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] (M.A.T.B.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (V.J.) 3 Dermfocus, Vetsuisse Faculty, University Hospital of Bern, 3010 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] 4 Institute of Animal Pathology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-979-862-1568 Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 3 August 2020; Published: 4 August 2020 Abstract: The transcriptome profile and differential gene expression in telogen and late anagen microdissected hair follicles and the interfollicular epidermis of healthy dogs was investigated by using RNAseq. The genes with the highest expression levels in each group were identified and genes known from studies in other species to be associated with structure and function of hair follicles and epidermis were evaluated. Transcriptome profiling revealed that late anagen follicles expressed mainly keratins and telogen follicles expressed GSN and KRT15. The interfollicular epidermis expressed predominately genes encoding for proteins associated with differentiation. All sample groups express genes encoding for proteins involved in cellular growth and signal transduction.